What Study Design Should I Choose?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levels of Evidence Table

Levels of Evidence All clinically related articles will require a Level-of-Evidence rating for classifying study quality. The Journal has five levels of evidence for each of four different study types; therapeutic, prognostic, diagnostic and cost effectiveness studies. Authors must classify the type of study and provide a level - of- evidence rating for all clinically oriented manuscripts. The level-of evidence rating will be reviewed by our editorial staff and their decision will be final. The following tables and types of studies will assist the author in providing the appropriate level-of- evidence. Type Treatment Study Prognosis Study Study of Diagnostic Test Cost Effectiveness of Study Study LEVEL Randomized High-quality Testing previously Reasonable I controlled trials prospective developed costs and with adequate cohort study diagnostic criteria alternatives used statistical power with > 80% in a consecutive in study with to detect follow-up, and series of patients values obtained differences all patients and a universally from many (narrow enrolled at same applied “gold” standard studies, study confidence time point in used multi-way intervals) and disease sensitivity follow up >80% analysis LEVEL Randomized trials Prospective cohort Development of Reasonable costs and II (follow up <80%, study (<80% follow- diagnostic criteria in a alternatives used in Improper up, patients enrolled consecutive series of study with values Randomization at different time patients and a obtained from limited Techniques) points in disease) universally -

Quasi-Experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: a Systematic Review

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Infect Control Manuscript Author Hosp Epidemiol Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 November 12. Published in final edited form as: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018 February ; 39(2): 170–176. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.296. Quasi-experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: A Systematic Review Rotana Alsaggaf, MS, Lyndsay M. O’Hara, PhD, MPH, Kristen A. Stafford, PhD, MPH, Surbhi Leekha, MBBS, MPH, Anthony D. Harris, MD, MPH, CDC Prevention Epicenters Program Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Abstract OBJECTIVE.—A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies in the field of infectious diseases was published in 2005. The aim of this study was to assess improvements in the design and reporting of quasi-experiments 10 years after the initial review. We also aimed to report the statistical methods used to analyze quasi-experimental data. DESIGN.—Systematic review of articles published from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014, in 4 major infectious disease journals. METHODS.—Quasi-experimental studies focused on infection control and antibiotic resistance were identified and classified based on 4 criteria: (1) type of quasi-experimental design used, (2) justification of the use of the design, (3) use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and (4) statistical methods used. RESULTS.—Of 2,600 articles, 173 (7%) featured a quasi-experimental design, compared to 73 of 2,320 articles (3%) in the previous review (P<.01). Moreover, 21 articles (12%) utilized a study design with a control group; 6 (3.5%) justified the use of a quasi-experimental design; and 68 (39%) identified their design using the correct nomenclature. -

Observational Clinical Research

E REVIEW ARTICLE Clinical Research Methodology 2: Observational Clinical Research Daniel I. Sessler, MD, and Peter B. Imrey, PhD * † Case-control and cohort studies are invaluable research tools and provide the strongest fea- sible research designs for addressing some questions. Case-control studies usually involve retrospective data collection. Cohort studies can involve retrospective, ambidirectional, or prospective data collection. Observational studies are subject to errors attributable to selec- tion bias, confounding, measurement bias, and reverse causation—in addition to errors of chance. Confounding can be statistically controlled to the extent that potential factors are known and accurately measured, but, in practice, bias and unknown confounders usually remain additional potential sources of error, often of unknown magnitude and clinical impact. Causality—the most clinically useful relation between exposure and outcome—can rarely be defnitively determined from observational studies because intentional, controlled manipu- lations of exposures are not involved. In this article, we review several types of observa- tional clinical research: case series, comparative case-control and cohort studies, and hybrid designs in which case-control analyses are performed on selected members of cohorts. We also discuss the analytic issues that arise when groups to be compared in an observational study, such as patients receiving different therapies, are not comparable in other respects. (Anesth Analg 2015;121:1043–51) bservational clinical studies are attractive because Group, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists they are relatively inexpensive and, perhaps more Anesthesia Quality Institute. importantly, can be performed quickly if the required Recent retrospective perioperative studies include data O 1,2 data are already available. -

Top Ten Cool Things About 250B Exam 1

Cohort Studies Madhukar Pai, MD, PhD McGill University Montreal 1 Cohort: origins of the word http://www.caerleon.net/ 2 Introduction • Measurement of the occurrence of events over time is a central goal of epidemiologic research • Regardless of any particular study design or hypothesis, interest is ultimately in the disease or outcome-causing properties of factors that are antecedent to the disease or outcome. • All study designs (including case control and cross- sectional studies) are played out in some populations over time (either well defined cohorts or not) – They differ in how they acknowledge time and how they sample exposed and non-exposed as these groups develop disease over time 3 All the action happens within a “sea of person-time” in which events occur 4 Morgenstern IJE 1980 Cohort studies Intuitive approach to studying disease incidence and risk factors: 1. Start with a population at risk 2. Measure exposures and covariates at baseline 3. Follow-up the cohort over time with a) Surveillance for events or b) re-examination 4. Keep track of attrition, withdrawals, drop-outs and competing risks 5. For covariates that change over time, measure them again during follow up 6. Compare event rates in people with and without exposures of interest - Incidence Density Ratio (IDR) is the most natural and appropriate measure of effect - Adjust for confounders and compute adjusted IDR - Look for effect measure modification, if appropriate 5 Cohort studies • Can be large or small • Can be long or short duration • Can be simple or elaborate • Can look at multiple exposures and multiple outcomes • Can look at changes in exposures over time • For rare outcomes need many people and/or lengthy follow- up • Are usually very expensive because of the numbers and follow-up requirements • But once a cohort is established, can sustain research productivity for a long, long time! 6 Cohort: keeping track of people 7 Szklo & Nieto. -

Epidemiologic Study Designs

Epidemiologic Study Designs Jacky M Jennings, PhD, MPH Associate Professor Associate Director, General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine Director, Center for Child & Community Health Research (CCHR) Departments of Pediatrics & Epidemiology Johns Hopkins University Learning Objectives • Identify basic epidemiologic study designs and their frequent sequence of study • Recognize the basic components • Understand the advantages and disadvantages • Appropriately select a study design Research Question & Hypotheses Analytic Study Plan Design Basic Study Designs and their Hierarchy Clinical Observation Hypothesis Descriptive Study Case-Control Study Cohort Study Randomized Controlled Trial Systematic Review Causality Adapted from Gordis, 1996 MMWR Study Design in Epidemiology • Depends on: – The research question and hypotheses – Resources and time available for the study – Type of outcome of interest – Type of exposure of interest – Ethics Study Design in Epidemiology • Includes: – The research question and hypotheses – Measures and data quality – Time – Study population • Inclusion/exclusion criteria • Internal/external validity Epidemiologic Study Designs • Descriptive studies – Seeks to measure the frequency of disease and/or collect descriptive data on risk factors • Analytic studies – Tests a causal hypothesis about the etiology of disease • Experimental studies – Compares, for example, treatments EXPOSURE Cross-sectional OUTCOME EXPOSURE OUTCOME Case-Control EXPOSURE OUTCOME Cohort TIME Cross-sectional studies • Measure existing disease and current exposure levels at one point in time • Sample without knowledge of exposure or disease • Ex. Prevalence studies Cross-sectional studies • Advantages – Often early study design in a line of investigation – Good for hypothesis generation – Relatively easy, quick and inexpensive…depends on question – Examine multiple exposures or outcomes – Estimate prevalence of disease and exposures Cross-sectional studies • Disadvantages – Cannot infer causality – Prevalent vs. -

Overview of Epidemiological Study Designs

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS PEER Liberia Project UMass Medical School Collaborations in Liberia 2018-11 Overview of Epidemiological Study Designs Richard Ssekitoleko Yale University Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/liberia_peer Part of the Clinical Epidemiology Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Family Medicine Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Education Commons, and the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons Repository Citation Ssekitoleko R. (2018). Overview of Epidemiological Study Designs. PEER Liberia Project. https://doi.org/ 10.13028/fp3z-mv12. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/liberia_peer/5 This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PEER Liberia Project by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Overview of Epidemiological study Designs Richard Ssekitoleko Department of Global Health Yale University 1.1 Objectives • Understand the different epidemiological study types • Get to know what is involved in each type of study • Understand the strengths and Limitations of each study type Key terms • Population • Consists of all elements and is the group from which a sample is drawn • A sample is a subset of a population • Parameters • Summary data from a population • Statistics • Summary data from a sample • Validity • Extent to which a conclusion or statistic is well-founded and likely corresponds accurately to the parameter. Hierarchy of Evidence Study type Observational Interventional Descriptive Experiment Ecological Randomized Controlled Trial Cross-sectional Case-control Cohort Overview of Epidemiologic Study Designs Validity *anecdotes Cost Understanding What Physicians Mean: In my experience … once. -

Common Types of Questions: Types of Study Designs

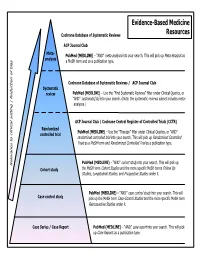

Evidence-Based Medicine Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Resources ACP Journal Club Meta- is as PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” meta-analysis into your search. This will pick up Meta-Analys analysis s a MeSH term and as a publication type. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews / ACP Journal Club Systematic review PubMed (MEDLINE) – Use the ”Find Systematic Reviews” filter under Clinical Queries, or “AND” systematic[sb] into your search. (Note: the systematic reviews subset includes meta- analyses.) tting | Reduction of bia ACP Journal Club / Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR) Randomized PubMed (MEDLINE) – Use the “Therapy” filter under Clinical Queries, or “AND” controlled trial randomized controlled trial into your search. This will pick up Randomized Controlled Trials as a MeSH term and Randomized Controlled Trial as a publication type. PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” cohort study into your search. This will pick up Relevance to clinical se Cohort study the MeSH term Cohort Studies and the more specific MeSH terms Follow Up Studies, Longitudinal Studies, and Prospective Studies under it. PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” case control study into your search. This will Case control study pick up the MeSH term Case-Control Studies and the more specific MeSH term Retrospective Studies under it. Case Series / Case Report PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” case report into your search. This will pick up Case Reports as a publication type. COMMON TYPES OF QUESTIONS: TYPES OF STUDY DESIGNS: Therapy -- how to select treatments to offer patients that do more good A Meta-analysis takes a systematic review one step further by than harm and that are worth the efforts and costs of using them combining all the results using accepted statistical methodology. -

Levels of Evidence

Levels of Evidence PLEASE NOTE: Evidence levels are only used for research involving human subjects. Basic science and animal studies should be listed as NA. Level Therapy/Prevention or Etiology/Harm Prognosis Study Study 1a Systematic review of randomized Systematic review of prospective cohort controlled trials studies 1b Individual randomized controlled trial Individual prospective cohort study 2a Systematic review of cohort studies Systematic review of retrospective cohort studies 2b Individual cohort study Individual retrospective cohort study 2c “Outcomes research” “Outcomes research” 3a Systematic review of case-control studies 3b Individual case-control study 4 Case series (with or without comparison) Case series (with or without comparison) 5 Expert opinion Expert opinion NA Animal studies and basic research Animal studies and basic research Case-Control Study. Case-control studies, which are always retrospective, compare those who have had an outcome or event (cases) with those who have not (controls). Cases and controls are then evaluated for exposure to various risk factors. Cases and controls generally are matched according to specific characteristics (eg, age, sex, or duration of disease). Case Series. A case series describes characteristics of a group of patients with a particular disease or patients who had undergone a particular procedure. A case series may also involve observation of larger units such as groups of hospitals or municipalities, as well as smaller units such as laboratory samples. Case series may be used to formulate a case definition of a disease or describe the experience of an individual or institution in treating a disease or performing a type of procedure. A case series is not used to test a hypothesis because there is no comparison group. -

Study Designs and Their Outcomes

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC CHAPTERNOT FOR SALE 3 OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © JonesStudy & Bartlett Designs Learning, LLC and Their Outcomes© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION “Natural selection is a mechanism for generating an exceedingly high degree of improbability.” —Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher Peter Wludyka © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION OBJECTIVES ______________________________________________________________________________ • Define research design, research study, and research protocol. • Identify the major features of a research study. • Identify© Jonesthe four types& Bartlett of designs Learning,discussed in this LLC chapter. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC • DescribeNOT nonexperimental FOR SALE designs, OR DISTRIBUTIONincluding cohort, case-control, and cross-sectionalNOT studies. FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION • Describe the types of epidemiological parameters that can be estimated with exposed cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies along with the role, appropriateness, and interpreta- tion of relative risk and odds ratios in the context of design choice. • Define true experimental design and describe its role in assessing cause-and-effect relation- © Jones &ships Bartlett along with Learning, definitions LLCof and discussion of the role of ©internal Jones and &external Bartlett validity Learning, in LLC NOT FOR evaluatingSALE OR designs. DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION • Describe commonly used experimental designs, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), after-only (post-test only) designs, the Solomon four-group design, crossover designs, and factorial designs. -

Cohort Studies and Relative Risks

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS PEER Liberia Project UMass Medical School Collaborations in Liberia 2019-2 Cohort Studies and Relative Risks Richard Ssekitoleko Yale University Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/liberia_peer Part of the Clinical Epidemiology Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Family Medicine Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Education Commons, and the Statistics and Probability Commons Repository Citation Ssekitoleko R. (2019). Cohort Studies and Relative Risks. PEER Liberia Project. https://doi.org/10.13028/ 17f0-7y26. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/liberia_peer/14 This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PEER Liberia Project by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cohort studies and Relative risks Richard Ssekitoleko Objectives • Define a cohort study and the steps for the study • Understand the populations in a cohort study • Understand timing in a cohort study and the difference between retrospective, prospective and ambi-directional cohort studies • Understand the selection of the cohort population and the collection of exposure and outcome data • Understand the sources of bias in a cohort study • Understand the calculation and interpretation of the relative risk • Understand use of the new-castle Ottawa quality assessment score for cohort studies -

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Retrospective Series of Regorafenib for Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer JOEY MERCIER 1 and IOANNIS A

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 37 : 5925-5934 (2017) doi:10.21873/anticanres.12039 Review A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Retrospective Series of Regorafenib for Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer JOEY MERCIER 1 and IOANNIS A. VOUTSADAKIS 1,2,3 1Northern Ontario School of Medicine, 2Division of Clinical Sciences, Sudbury, ON, Canada; 3Algoma District Cancer Program, Sault Area Hospital, Sault Ste Marie, ON, Canada Abstract. Background: Metastatic colorectal cancer is a IIIb studies. Most common adverse effects were also common disease encountered in oncology practice and consistent with those of the published phase III experience. treatment options beyond fluoropyrimidines, irinotecan, Conclusion: This systematic review and meta-analysis oxaliplatin and monoclonal antibodies against epidermal confirmed a moderate efficacy of regorafenib in later-stage growth factor receptor and vascular endothelium growth metastatic colorectal cancer in the everyday clinical practice factor (VEGF) are limited. Regorafenib, a new drug that setting outside of clinical trials. Future identification of targets tyrosine kinases such as VEGF receptor as well as biomarkers may aid in further tailoring of this treatment in others, has been added recently to the armamentarium for order to obtain maximum clinical benefit. metastatic colorectal cancer. This report analyzes the published experience with this drug in clinical practice Colorectal cancer is the most common gastrointestinal outside of clinical trials. Materials and Methods: A literature malignancy in the Western world and remains a prominent search of major databases was performed for the cause of cancer morbidity and mortality, despite progress in identification of studies of regorafenib in metastatic its management. It affects approximately 746,000 men and colorectal cancer. -

Cohort, Cross Sectional, and Case-Control Studies C J Mann

54 RESEARCH SERIES Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.20.1.54 on 1 January 2003. Downloaded from Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies C J Mann ............................................................................................................................. Emerg Med J 2003;20:54–60 Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies are While an appropriate choice of study design is collectively referred to as observational studies. Often vital, it is not sufficient. The hallmark of good research is the rigor with which it is conducted. A these studies are the only practicable method of checklist of the key points in any study irrespec- studying various problems, for example, studies of tive of the basic design is given in box 1. aetiology, instances where a randomised controlled trial Every published study should contain suffi- cient information to allow the reader to analyse might be unethical, or if the condition to be studied is the data with reference to these key points. rare. Cohort studies are used to study incidence, causes, In this article each of the three important and prognosis. Because they measure events in observational research methods will be discussed with emphasis on their strengths and weak- chronological order they can be used to distinguish nesses. In so doing it should become apparent between cause and effect. Cross sectional studies are why a given study used a particular research used to determine prevalence. They are relatively quick method and which method might best answer a particular clinical problem. and easy but do not permit distinction between cause and effect. Case controlled studies compare groups COHORT STUDIES retrospectively.