NOAA Spotter Reference Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast

Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast John T. Snow Regents’ Professor of Meteorology Dean Emeritus, College of Atmospheric and Geographic Sciences, The University of Oklahoma Major contributions from: Dr. Russel Schneider –NOAA Storm Prediction Center Dr. David Stensrud – NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Dr. Ming Xue –Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, University of Oklahoma Dr. Lou Wicker –NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Hazards Caucus Alliance Briefing Tornadoes: Understanding how they develop and providing early warning 10:30 am – 11:30 am, Wednesday, 21 July 2010 Senate Capitol Visitors Center 212 Each Year: ~1,500 tornadoes touch down in the United States, causing over 80 deaths, 100s of injuries, and an estimated $1.1 billion in damages Statistics from NOAA Storm Prediction Center Supercell –A long‐lived rotating thunderstorm the primary type of thunderstorm producing strong and violent tornadoes Present Warning System: Warn on Detection • A Warning is the culmination of information developed and distributed over the preceding days sequence of day‐by‐day forecasts identifies an area of high threat •On the day, storm spotters deployed; radars monitor formation, growth of thunderstorms • Appearance of distinct cloud or radar echo features tornado has formed or is about to do so Warning is generated, distributed Present Warning System: Warn on Detection Radar at 2100 CST Radar at 2130 CST with Warning Thunderstorms are monitored using radar A warning is issued based on the detected and -

The Generation of a Mesoscale Convective System from Mountain Convection

JUNE 1999 TUCKER AND CROOK 1259 The Generation of a Mesoscale Convective System from Mountain Convection DONNA F. T UCKER Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas N. ANDREW CROOK National Center for Atmospheric Research Boulder, Colorado (Manuscript received 18 November 1997, in ®nal form 13 July 1998) ABSTRACT A mesoscale convective system (MCS) that formed just to the east of Denver is investigated with a nonhy- drostatic numerical model to determine which processes were important in its initiation. The MCS developed from out¯ow from previous convective activity in the Rocky Mountains to the west. Model results indicate that this out¯ow was necessary for the development of the MCS even though a convergence line was already present in the area where the MCS developed. A simulation with a 3-km grid spacing more fully resolves the convective activity in the mountains but the development of the MCS can be simulated with a 6.67-km grid. Cloud effects on solar radiation and ice sedimentation both in¯uence the strength of the out¯ow from the mountain convection but only the ice sedimentation makes a signi®cant impact on the development of the MCS after its initiation. The frequent convective activity in the Rocky Mountains during the warm season provides out¯ow that would make MCS generation favorable in this region. Thus, there is a close connection between mountain convective activity and MCS generation. The implications of such a connection are discussed and possible directions of future research are indicated. 1. Introduction scale or mesoscale. Forced lifting always occurs on the windward side of mountains; however, the mechanisms Mesoscale convective systems (MCSs) commonly de- that promote lifting on the downwind side of mountains, velop in the central United States during the warm sea- where a large proportion of MCSs initiate, are not as son, accounting for 30%±70% of the summer precipi- obvious. -

3. Electrical Structure of Thunderstorm Clouds

3. Electrical Structure of Thunderstorm Clouds 1 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification An isolated thundercloud in the central New Mexico, with rudimentary indication of how electric charge is thought to be distributed and around the thundercloud, as inferred from the remote and in situ observations. Adapted from Krehbiel (1986). 2 2 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification A vertical tripole representing the idealized gross charge structure of a thundercloud. The negative screening layer charges at the cloud top and the positive corona space charge produced at ground are ignored here. 3 3 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification E = 2 E (−)cos( 90o−α) Q H = 2 2 3/2 2πεo()H + r sinα = k Q = const R2 ( ) Method of images for finding the electric field due to a negative point charge above a perfectly conducting ground at a field point located at the ground surface. 4 4 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification The electric field at ground due to the vertical tripole, labeled “Total”, as a function of the distance from the axis of the tripole. Also shown are the contributions to the total electric field from the three individual charges of the tripole. An upward directed electric field is defined as positive (according to the physics sign convention). 5 5 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification Electric Field Change Due to Negative Cloud-to-Ground Discharge Electric Field Change Due to a Cloud Discharge Electric Field Change, kV/m Change, Electric Field Electric Field Change, kV/m Change, Electric Field Distance, km Distance, km Electric field change at ground, due to the Electric field change at ground, due to the total removal of the negative charge of the total removal of the negative and upper vertical tripole via a cloud-to-ground positive charges of the vertical tripole via a discharge, as a function of distance from cloud discharge, as a function of distance from the axis of the tripole. -

The Impact of Outflow Environment on Tropical Cyclone Intensification And

VOLUME 68 JOURNAL OF THE ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES FEBRUARY 2011 The Impact of Outflow Environment on Tropical Cyclone Intensification and Structure ERIC D. RAPPIN Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Miami, Miami, Florida MICHAEL C. MORGAN AND GREGORY J. TRIPOLI University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, Wisconsin (Manuscript received 3 October 2008, in final form 5 June 2009) ABSTRACT In this study, the impacts of regions of weak inertial stability on tropical cyclone intensification and peak strength are examined. It is demonstrated that weak inertial stability in the outflow layer minimizes an energy sink of the tropical cyclone secondary circulation and leads to more rapid intensification to the maximum potential intensity. Using a full-physics, three-dimensional numerical weather prediction model, a symmetric distribution of environmental inertial stability is generated using a variable Coriolis parameter. It is found that the lower the value of the Coriolis parameter, the more rapid the strengthening. The lower-latitude simulation is shown to have a significantly stronger secondary circulation with intense divergent outflow against a com- paratively weak environmental resistance. However, the impacts of differences in the gradient wind balance between the different latitudes on the core structure cannot be neglected. A second study is then conducted using an asymmetric inertial stability distribution generated by the presence of a jet stream to the north of the tropical cyclone. The initial intensification is similar, or even perhaps slower, in the presence of the jet as a result of increased vertical wind shear. As the system evolves, convective outflow from the tropical cyclone modifies the jet resulting in weaker shear and more rapid intensification of the tropical cyclone–jet couplet. -

From the Line in the Sand: Accounts of USAF Company Grade Officers In

~~may-='11 From The Line In The Sand Accounts of USAF Company Grade Officers Support of 1 " 1 " edited by gi Squadron 1 fficer School Air University Press 4/ Alabama 6" March 1994 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data From the line in the sand : accounts of USAF company grade officers in support of Desert Shield/Desert Storm / edited by Michael P. Vriesenga. p. cm. Includes index. 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991-Aerial operations, American . 2. Persian Gulf War, 1991- Personai narratives . 3. United States . Air Force-History-Persian Gulf War, 1991 . I. Vriesenga, Michael P., 1957- DS79 .724.U6F735 1994 94-1322 959.7044'248-dc20 CIP ISBN 1-58566-012-4 First Printing March 1994 Second Printing September 1999 Third Printing March 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts . The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication hasbeen reviewed by security andpolicy review authorities and is clearedforpublic release. For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents US Government Printing Office Washington, D.C . 20402 ii 9&1 gook L ar-dicat£a to com#an9 9zacL orflcF-T 1, #ait, /2ZE4Ent, and, E9.#ECLaL6, TatUlLE. -ZEa¢ra anJ9~ 0 .( THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Essay Page DISCLAIMER .... ... ... .... .... .. ii FOREWORD ...... ..... .. .... .. xi ABOUT THE EDITOR . ..... .. .... xiii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ..... .. .... xv INTRODUCTION .... ..... .. .. ... xvii SUPPORT OFFICERS 1 Madzuma, Michael D., and Buoniconti, Michael A. -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

Tornadoes & Funnel Clouds Fake Tornado

NOAA’s National Weather Service Basic Concepts of Severe Storm Spotting 2009 – Rusty Kapela Milwaukee/Sullivan weather.gov/milwaukee Housekeeping Duties • How many new spotters? - if this is your first spotter class & you intend to be a spotter – please raise your hands. • A basic spotter class slide set & an advanced spotter slide set can be found on the Storm Spotter Page on the Milwaukee/Sullivan web site (handout). • Utilize search engines and You Tube to find storm videos and other material. Class Agenda • 1) Why we are here • 2) National Weather Service Structure & Role • 3) Role of Spotters • 4) Types of reports needed from spotters • 5) Thunderstorm structure • 6) Shelf clouds & rotating wall clouds • 7) You earn your “Learner’s Permit” Thunderstorm Structure Those two cloud features you were wondering about… Storm Movement Shelf Cloud Rotating Wall Cloud Rain, Hail, Downburst winds Tornadoes & Funnel Clouds Fake Tornado It’s not rotating & no damage! Let’s Get Started! Video Why are we here? Parsons Manufacturing 120-140 employees inside July 13, 2004 Roanoke, IL Storm shelters F4 Tornado – no injuries or deaths. They have trained spotters with 2-way radios Why Are We Here? National Weather Service’s role – Issue warnings & provide training Spotter’s role – Provide ground-truth reports and observations We need (more) spotters!! National Weather Service Structure & Role • Federal Government • Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service 122 Field Offices, 6 Regional, 13 River Forecast Centers, Headquarters, other specialty centers Mission – issue forecasts and warnings to minimize the loss of life & property National Weather Service Forecast Office - Milwaukee/Sullivan Watch/Warning responsibility for 20 counties in southeast and south- central Wisconsin. -

An Observational Analysis Quantifying the Distance of Supercell-Boundary Interactions in the Great Plains

Magee, K. M., and C. E. Davenport, 2020: An observational analysis quantifying the distance of supercell-boundary interactions in the Great Plains. J. Operational Meteor., 8 (2), 15-38, doi: https://doi.org/10.15191/nwajom.2020.0802 An Observational Analysis Quantifying the Distance of Supercell-Boundary Interactions in the Great Plains KATHLEEN M. MAGEE National Weather Service Huntsville, Huntsville, AL CASEY E. DAVENPORT University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC (Manuscript received 11 June 2019; review completed 7 October 2019) ABSTRACT Several case studies and numerical simulations have hypothesized that baroclinic boundaries provide enhanced horizontal and vertical vorticity, wind shear, helicity, and moisture that induce stronger updrafts, higher reflectivity, and stronger low-level rotation in supercells. However, the distance at which a surface boundary will provide such enhancement is less well-defined. Previous studies have identified enhancement at distances ranging from 10 km to 200 km, and only focused on tornado production and intensity, rather than all forms of severe weather. To better aid short-term forecasts, the observed distances at which supercells produce severe weather in proximity to a boundary needs to be assessed. In this study, the distance between a large number of observed supercells and nearby surface boundaries (including warm fronts, stationary fronts, and outflow boundaries) is measured throughout the lifetime of each storm; the distance at which associated reports of large hail and tornadoes occur is also collected. Statistical analyses assess the sensitivity of report distributions to report type, boundary type, boundary strength, angle of interaction, and direction of storm motion relative to the boundary. -

911 Communicator Questions to Ask Of

911 Communicator Questions to ask of Severe Weather Spotters 1. Name, home address, and telephone number. 2. Is caller a trained severe weather spotter. 3. Time of call. 4. Time of severe weather event (may be different than call time). 5. Location of severe weather event, which may be different from location where spotter called from. (If spotter doesn’t say 1.2 miles southeast of Anytown, then request names of streets at nearest intersection). 6. Type of Weather Event – (most common to least common order) a. If it’s a wind report, ask if the reported speed is measured or estimated. b. If it’s a wind damage report, ask caller to estimate how many trees are damaged, uprooted, etc., or extent and severity of structural damage. c. If it’s a hail event, ask if the reported size is measured or estimated. (penny, nickel, quarter, golf ball, soft ball, etc.) d. If it’s a flood report, ask caller to estimate depth of water on roads or on lawns, ask if the water is stationary or moving, and extent or severity of damage. e. If it’s a “rotating wall-cloud” report, i. Persistent rotation (usually on backside of storm) = true rotating wall-cloud. ii. No rotation = scary-looking cloud (scud), or a non-rotating wall-cloud. f. If it’s a funnel-cloud report, ask caller if the funnel-shaped cloud is actually rotating. If the caller is too far away from the funnel-cloud they may not be able to see rotation. i. No rotation = just a scary-looking cloud (scud). -

More Observations of Small Funnel Clouds and Other Tubular Clouds

3714 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 133 PICTURE OF THE MONTH More Observations of Small Funnel Clouds and Other Tubular Clouds HOWARD B. BLUESTEIN School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 14 March 2005, in final form 20 May 2005) ABSTRACT In this brief contribution, photographic documentation is provided of a variety of small, tubular-shaped clouds and of a small funnel cloud pendant from a convective cloud that appears to have been modified by flow over high-altitude mountains in northeast Colorado. These funnel clouds are contrasted with others that have been documented, including those pendant from high-based cumulus clouds in the plains of the United States. It is suggested that the mountain funnel cloud is unique in that flow over high terrain is probably responsible for its existence; other types of small funnel clouds are seen both over elevated, mountainous terrain and over flat terrain at lower elevations. 1. Introduction which the benign funnel clouds occur so that if they are observed, severe weather warnings are not issued. Fur- Bluestein (1994) and others (e.g., Doswell 1985, p. thermore, the small funnel clouds are of interest in their 107; McCaul and Blanchard 1990) have documented, in own right because their dynamics are not well under- the plains of the United States, small funnel clouds pen- stood, and they have not been discussed in the litera- dant from convective clouds whose updrafts appear to ture to the much greater extent that the dynamics of be rooted above the boundary layer. Above many of tornadoes have (e.g., Davies-Jones 1986). -

The Lagrange Torando During Vortex2. Part Ii: Photogrammetry Analysis of the Tornado Combined with Dual-Doppler Radar Data

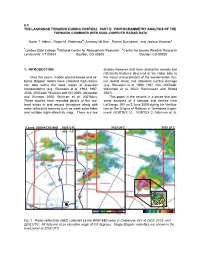

6.3 THE LAGRANGE TORANDO DURING VORTEX2. PART II: PHOTOGRAMMETRY ANALYSIS OF THE TORNADO COMBINED WITH DUAL-DOPPLER RADAR DATA Nolan T. Atkins*, Roger M. Wakimoto#, Anthony McGee*, Rachel Ducharme*, and Joshua Wurman+ *Lyndon State College #National Center for Atmospheric Research +Center for Severe Weather Research Lyndonville, VT 05851 Boulder, CO 80305 Boulder, CO 80305 1. INTRODUCTION studies, however, that have related the velocity and reflectivity features observed in the radar data to Over the years, mobile ground-based and air- the visual characteristics of the condensation fun- borne Doppler radars have collected high-resolu- nel, debris cloud, and attendant surface damage tion data within the hook region of supercell (e.g., Bluestein et al. 1993, 1197, 204, 2007a&b; thunderstorms (e.g., Bluestein et al. 1993, 1997, Wakimoto et al. 2003; Rasmussen and Straka 2004, 2007a&b; Wurman and Gill 2000; Alexander 2007). and Wurman 2005; Wurman et al. 2007b&c). This paper is the second in a series that pre- These studies have revealed details of the low- sents analyses of a tornado that formed near level winds in and around tornadoes along with LaGrange, WY on 5 June 2009 during the Verifica- radar reflectivity features such as weak echo holes tion on the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes Exper- and multiple high-reflectivity rings. There are few iment (VORTEX 2). VORTEX 2 (Wurman et al. 5 June, 2009 KCYS 88D 2002 UTC 2102 UTC 2202 UTC dBZ - 0.5° 100 Chugwater 100 50 75 Chugwater 75 330° 25 Goshen Co. 25 km 300° 50 Goshen Co. 25 60° KCYS 30° 30° 50 80 270° 10 25 40 55 dBZ 70 -45 -30 -15 0 15 30 45 ms-1 Fig. -

June 18, 2017 Landspout Tornadoes

June 18, 2017 Landspout Tornadoes During the evening hours of Sunday, June 18, thunderstorms developed in the vicinity of a cold front over Reagan and Upton Counties.As a result of intense heating and an incredible amount of instability along this boundary, three EF0 landspout* (see definitionat bottom of report) tornadoes touched down in Reagan and southeast Upton Counties between 7 and 8 pm CDT. These tornadoes occurred in open country and no damage was reported. Tornado #1 – EF0: Southwest Reagan County to Southeast Upton County (~7:05-7:13 pm CDT) The first thunderstorm developed around 6:00 pm near Big Lake, TX and slowly moved west along and near US Hwy 67. Law enforcement officersand folks in the area viewed and took images of a tornado that developed 1-2 miles south of US Hwy 67 roughly 14 miles east of Big Lake and continued westward through open fields insouth east portions of Upton County. The tornado was narrow, perhaps 50-75 yards in width and no damage was reported with this tornado. Photo by Maybell Carrasco Photo by Greg Romero Tornado #2 – EF0: Central Reagan Photo by Shanna Gibson County (~8:00 pm CDT) Another thunderstorm moving west, entered eastern Reagan County around 7:30 pm. As this storm approached Big Lake, a second tornado was spotted around 8 pm roughly 6-7 miles northeast of Big Lake, 2-3 miles east of SH 137. This tornado was very short-lived and went undetected on radar. It occurred in open country and no damage was reported. Tornado #3 – EF0: Northeast Reagan County – approximately 20-25 miles north of Big Lake.