Thunderstorms & Lightning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avoiding the Risks of Deadly Lightning Strikes

Avoiding the Risks of Deadly Lightning Strikes Lightning is one of the most underrated severe weather hazards, yet ranks as the second-leading weather killer in the United States. More deadly than hurricanes or tornadoes, lightning strikes in America each year kill an average of 73 people and injure 300 others, according to NOAA's National Weather Service. How Lightning Works Lightning is caused by the attraction between positive and negative charges in the atmosphere, resulting in the buildup and discharge of electrical energy. This rapid heating and cooling of the air produces the shock wave that results in thunder. During a storm, raindrops can acquire extra electrons, which are negatively charged. These surplus electrons seek out a positive charge from the ground. As they flow from the clouds, they knock other electrons free, creating a conductive path. This path follows a zigzag shape that jumps between randomly distributed clumps of charged particles in the air. When the two charges connect, current surges through that jagged path, creating the lightning bolt. The Warning Signs High winds, rainfall, and a darkening cloud cover are the warning signs for possible cloud-to- ground lightning strikes. While many lightning casualties happen at the beginning of an approaching storm, more than 50 percent of lightning deaths occur after the thunderstorm has passed. The lightning threat diminishes after the last sound of thunder, but may persist for more than 30 minutes. When thunderstorms are in the area, but not overhead, the lightning threat can exist when skies are clear. Safety Precautions While nothing offers absolute safety from lightning, some actions can greatly reduce your risks. -

3. Electrical Structure of Thunderstorm Clouds

3. Electrical Structure of Thunderstorm Clouds 1 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification An isolated thundercloud in the central New Mexico, with rudimentary indication of how electric charge is thought to be distributed and around the thundercloud, as inferred from the remote and in situ observations. Adapted from Krehbiel (1986). 2 2 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification A vertical tripole representing the idealized gross charge structure of a thundercloud. The negative screening layer charges at the cloud top and the positive corona space charge produced at ground are ignored here. 3 3 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification E = 2 E (−)cos( 90o−α) Q H = 2 2 3/2 2πεo()H + r sinα = k Q = const R2 ( ) Method of images for finding the electric field due to a negative point charge above a perfectly conducting ground at a field point located at the ground surface. 4 4 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification The electric field at ground due to the vertical tripole, labeled “Total”, as a function of the distance from the axis of the tripole. Also shown are the contributions to the total electric field from the three individual charges of the tripole. An upward directed electric field is defined as positive (according to the physics sign convention). 5 5 Cloud Charge Structure and Mechanisms of Cloud Electrification Electric Field Change Due to Negative Cloud-to-Ground Discharge Electric Field Change Due to a Cloud Discharge Electric Field Change, kV/m Change, Electric Field Electric Field Change, kV/m Change, Electric Field Distance, km Distance, km Electric field change at ground, due to the Electric field change at ground, due to the total removal of the negative charge of the total removal of the negative and upper vertical tripole via a cloud-to-ground positive charges of the vertical tripole via a discharge, as a function of distance from cloud discharge, as a function of distance from the axis of the tripole. -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

Climatic Information of Western Sahel F

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Clim. Past Discuss., 10, 3877–3900, 2014 www.clim-past-discuss.net/10/3877/2014/ doi:10.5194/cpd-10-3877-2014 CPD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 10, 3877–3900, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Climate of the Past (CP). Climatic information Please refer to the corresponding final paper in CP if available. of Western Sahel V. Millán and Climatic information of Western Sahel F. S. Rodrigo (1535–1793 AD) in original documentary sources Title Page Abstract Introduction V. Millán and F. S. Rodrigo Conclusions References Department of Applied Physics, University of Almería, Carretera de San Urbano, s/n, 04120, Almería, Spain Tables Figures Received: 11 September 2014 – Accepted: 12 September 2014 – Published: 26 September J I 2014 Correspondence to: F. S. Rodrigo ([email protected]) J I Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 3877 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract CPD The Sahel is the semi-arid transition zone between arid Sahara and humid tropical Africa, extending approximately 10–20◦ N from Mauritania in the West to Sudan in the 10, 3877–3900, 2014 East. The African continent, one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change, 5 is subject to frequent droughts and famine. One climate challenge research is to iso- Climatic information late those aspects of climate variability that are natural from those that are related of Western Sahel to human influences. -

90001602.Pdf

Kobe University Repository : Kernel タイトル Prediction of human thermophysiological responses during shower Title bathing 著者 Abdul, Munir / Takada, Satoru / Matsushita, Takayuki / Kubo, Hiroko Author(s) 掲載誌・巻号・ページ International Journal of Biometeorology,54(2):165-178 Citation 刊行日 2010-03 Issue date 資源タイプ Journal Article / 学術雑誌論文 Resource Type 版区分 author Resource Version 権利 Rights DOI 10.1007/s00484-009-0265-9 JaLCDOI URL http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/handle_kernel/90001602 PDF issue: 2021-09-29 PREDICTION OF HUMAN THERMOPHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES DURING SHOWER BATHING Abdul Munir Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Syiah Kuala University, Darussalam, Banda Aceh 23111, Indonesia Satoru Takada Department of Architecture, Graduate School of Engineering, Kobe University, Rokko, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan Phone: +81 78 803 6038 Fax: +81 78 803 6038 Email: [email protected] Takayuki Matsushita Department of Architecture, Graduate School of Engineering, Kobe University, Rokko, Nada, Kobe 657-8501, Japan Hiroko Kubo Department of Environmental Health, Faculty of Human Life and Environment, Nara Women's University, Kitauoya-nishimachi, Nara 630-8506, Japan ABSTRACT This study develops a model to predict the thermophysiological response of the human body during shower bathing. Despite the needs for the quantitative evaluation of human body response during bathing for thermal comfort and safety, the complicated mechanisms of heat transfer at the skin surface, especially 1 during shower bathing, have disturbed the development of adequate models. In this study, an initial modeling approach is proposed by developing a simple heat transfer model at the skin surface during shower bathing, applied to Stolwijk’s human thermal model. -

Electrified Shower Clouds and Their Contribution to the Global Electrical Circuit” (Liu Et

Contribution of Thunderstorms and Shower Clouds to the Global Electric Circuit Review of “Diurnal Variations of Global Thunderstorms and Electrified Shower Clouds and Their Contribution to the Global Electrical Circuit” (Liu et. al. 2010) Kyle Chudler ATS 780 • Two main discrepancies • Amplitude of thunder days is Thunder Days and Carnegie Curve ~2 times that of Carnegie curve • Phases misaligned • Thunder Day curve max: Africa (14 – 15 UTC) • Carnegie curve max: South America (19 – 20 UTC) • Possible explanations: • Ocean not accounted for • Non-lightning producing precipitation (electrified shower clouds) • Try to use TRMM data to get a Whipple (1929) handle on both of these Methods • TRMM Precipitation Features • Groups contiguous raining pixels into one feature • Can get statistics of individual PF’s (max echo height, precipitation volume, etc.) • Divide PFs into thunderstorms, electrified shower clouds, and non-electrified • Thunderstorm: PF’s with at least one lightning flash (LIS) • Electrified Shower Cloud: , T30dBZ < -10 C over land and T30dBZ < -17 C over ocean • Only look at PF’s > 75 km2 • 75% of population, but <10% of rainfall and rain area • Compare several diurnal cycles to Carnegie curve • Rainfall • Total, On/Off Land, Thunderstorm vs Electrified Shower • Total Lightning • Contrast amplitude and phases of cycles • More PFs over Ocean (81%) than land (19%) • Thunderstorms • ~1/200 PFs • 25% of rainfall • Electrified Shower Clouds • ~1/200 PFs • 15% of rainfall Non-electrified Rainfall Dominates Ocean Diurnal Rainfall vs. Carnegie Curve • Total rainfall (black line) has similar phase, smaller amplitude • Includes ocean, which has weaker diurnal signal • Best match is land rainfall • 60% of land rainfall is from electrified storms/showers • Best amplitude match of all cycles Diurnal Rainfall vs. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Downloaded 09/26/21 01:53 PM UTC VOL

418 BULLETIN AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY Forecasting Summertime Shower Activity at Grand Junction, Colorado WOODROW W. DICKEY U. S. Weather Bureau ABSTRACT Due to the lack of a dense network of reporting stations in the Grand Junction, Colorado area and the inadequate representation of shower activity by observations of rain at a single rain gage, certain arbitrary criteria were set up to define a "shower" day at Grand Junction. Relationships of a number of meteorological variables to shower activity were determined and the four variables which showed the strongest relationships were combined graphically to form an objective forecast aid for determining the probability of shower activity at Grand Junction during the 18-hour period 1130MST to 0530MST. Tests on independent data confirm the relationship found in the developmental data. INTRODUCTION accuracy equal to those that have been issued in the past. HIS study was initiated with the objec- tive of providing one of a number of DEFINITION OF A SHOWER DAY AT objective aids for forecasting various T GRAND JUNCTION weather elements in the Grand Junction, Colorado area. Specifically it was aimed at forecasting Summertime shower activity even in a rela- July and August shower activity during the pe- tively small area is not adequately represented by riod 1130MST to 0530MST the following morn- observation of rain at a single rain gage. Lack- ing, the forecast to be based on data available no ing a dense network of reporting stations in the later than 0530MST of the forecast morning. Grand Junction area, an attempt was made to Since the aid was to be used for the generalized obtain a more representative picture of shower weather forecast which is normally released to activity by inspecting the remarks entered on the the public, no attempt was made to pinpoint the WBAN Form 1130's and setting up certain arbi- trary criteria for deciding if the day were a forecast with respect to time, and a deliberate "shower day" or not. -

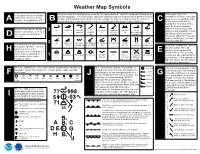

Print Key. (Pdf)

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature. -

Severe Weather Forecasting Tip Sheet: WFO Louisville

Severe Weather Forecasting Tip Sheet: WFO Louisville Vertical Wind Shear & SRH Tornadic Supercells 0-6 km bulk shear > 40 kts – supercells Unstable warm sector air mass, with well-defined warm and cold fronts (i.e., strong extratropical cyclone) 0-6 km bulk shear 20-35 kts – organized multicells Strong mid and upper-level jet observed to dive southward into upper-level shortwave trough, then 0-6 km bulk shear < 10-20 kts – disorganized multicells rapidly exit the trough and cross into the warm sector air mass. 0-8 km bulk shear > 52 kts – long-lived supercells Pronounced upper-level divergence occurs on the nose and exit region of the jet. 0-3 km bulk shear > 30-40 kts – bowing thunderstorms A low-level jet forms in response to upper-level jet, which increases northward flux of moisture. SRH Intense northwest-southwest upper-level flow/strong southerly low-level flow creates a wind profile which 0-3 km SRH > 150 m2 s-2 = updraft rotation becomes more likely 2 -2 is very conducive for supercell development. Storms often exhibit rapid development along cold front, 0-3 km SRH > 300-400 m s = rotating updrafts and supercell development likely dryline, or pre-frontal convergence axis, and then move east into warm sector. BOTH 2 -2 Most intense tornadic supercells often occur in close proximity to where upper-level jet intersects low- 0-6 km shear < 35 kts with 0-3 km SRH > 150 m s – brief rotation but not persistent level jet, although tornadic supercells can occur north and south of upper jet as well. -

Severe Thunderstorm Safety

Severe Thunderstorm Safety Thunderstorms are dangerous because they include lightning, high winds, and heavy rain that can cause flash floods. Remember, it is a severe thunderstorm that produces a tornado. By definition, a thunderstorm is a rain shower that contains lightning. A typical storm is usually 15 miles in diameter lasting an average of 30 to 60 minutes. Every thunderstorm produces lightning, which usually kills more people each year than tornadoes. A severe thunderstorm is a thunderstorm that contains large hail, 1 inch in diameter or larger, and/or damaging straight-line winds of 58 mph or greater (50 nautical mph). Rain cooled air descending from a severe thunderstorms can move at speeds in excess of 100 mph. This is what is called “straight-line” wind gusts. There were 12 injuries from thunderstorm wind gusts in Missouri in 2014, with only 5 injuries from tornadoes. A downburst is a sudden out-rush of this wind. Strong downbursts can produce extensive damage which is often similar to damage produced by a small tornado. A downburst can easily overturn a mobile home, tear roofs off houses and topple trees. Severe thunderstorms can produce hail the size of a quarter (1 inch) or larger. Quarter- size hail can cause significant damage to cars, roofs, and can break windows. Softball- size hail can fall at speeds faster than 100 mph. Thunderstorm Safety Avoid traveling in a severe thunderstorm – either pull over or delay your travel plans. When a severe thunderstorm threatens, follow the same safety rules you do if a tornado threatens. Go to a basement if available. -

Thunderstorm Predictors and Their Forecast Skill for the Netherlands

Atmospheric Research 67–68 (2003) 273–299 www.elsevier.com/locate/atmos Thunderstorm predictors and their forecast skill for the Netherlands Alwin J. Haklander, Aarnout Van Delden* Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC Utrecht, The Netherlands Accepted 28 March 2003 Abstract Thirty-two different thunderstorm predictors, derived from rawinsonde observations, have been evaluated specifically for the Netherlands. For each of the 32 thunderstorm predictors, forecast skill as a function of the chosen threshold was determined, based on at least 10280 six-hourly rawinsonde observations at De Bilt. Thunderstorm activity was monitored by the Arrival Time Difference (ATD) lightning detection and location system from the UK Met Office. Confidence was gained in the ATD data by comparing them with hourly surface observations (thunder heard) for 4015 six-hour time intervals and six different detection radii around De Bilt. As an aside, we found that a detection radius of 20 km (the distance up to which thunder can usually be heard) yielded an optimum in the correlation between the observation and the detection of lightning activity. The dichotomous predictand was chosen to be any detected lightning activity within 100 km from De Bilt during the 6 h following a rawinsonde observation. According to the comparison of ATD data with present weather data, 95.5% of the observed thunderstorms at De Bilt were also detected within 100 km. By using verification parameters such as the True Skill Statistic (TSS) and the Heidke Skill Score (Heidke), optimal thresholds and relative forecast skill for all thunderstorm predictors have been evaluated.