Pellitteri, Angelo OH552

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2014 Newsletter of Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory Number 45 the PRIMARY SOURCE

Spring/Summer 2014 Newsletter of Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory Number 45 THE PRIMARY SOURCE Our mission is to conserve birds and their habitats. RMBO Leads Landmark Meeting in Costa Rica By Teddy Parker-Renga to breeding, threats to non-breeding and it’s important for RMBO and partners to Communications Manager population trend) using the Partners In support and advance conservation abroad, In March, Rocky Mountain Bird Flight species assessment process. Scores he said. Observatory spearheaded the first-ever ranged from 1 (low vulnerability) to 5 Next steps include developing com- conservation assessment of the birds of (high vulnerability) for each factor, with munication tools and messages to engage Central America. a higher overall score indicating a greater stakeholders in conserving at-risk species. At the meeting held in San Vito, Costa vulnerability to population decline or Thank you to all of the partners who Rica, 30 participants representing the extinction. attended the meeting and Environment seven Central American countries, Mexico International Director Arvind Panjabi Canada, Missouri Department of Conser- and the U.S. assessed all 407 bird species said partners who attended the meeting vation and USGS for funding. unique to Central America, as well as 500- saw tremendous value in the process as View photos from the meeting and the plus species shared between Mexico and a way to establish conservation priori- amazing species we saw birding in Costa Central America. This included landbirds, ties for birds and habitat in their own Rica at www.facebook.com/RMBObirds. shorebirds, waterbirds and waterfowl. countries. Since many bird species that To learn more about the Partners In During the assessment, birds were breed in the Rockies and elsewhere in the Flight species assessment process, visit http:// assigned scores for three factors (threats western U.S. -

Oral History Interview with Howard Finster, 1984 June 11

Oral history interview with Howard Finster, 1984 June 11 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface Preface Interview with The Reverend Howard Finster conducted by Liza Kirwin in the Finley Conference Room at the National Museum of American Art and National Portrait Gallery building, Washington, D.C., June 11, 1984. Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape recorded interview with Howard Finster on June 11, 1984. The interview took place in Washington, D.C., and was conducted by Liza Kirwin for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. While we have made an attempt to convey The Reverend Finster’s speech pattern and dialect, the reader should bear in mind that this is a verbatim transcript of spoken, rather than written prose Interview LIZA KIRWIN: Mr. Finster, could you begin by talking about when and where you were born, and a little bit about your family background? HOWARD FINSTER: Yeah, I’ll start talking and you just break in when you want to because I never quit, you know. Just break if I talk too long. I was born at Valley Head, Alabama. It’s about 42 miles south of Chattanooga and about 200 miles west of Atlanta. I was born there in Alabama. I stayed on the farm a good while–with my father and mother and farm. -

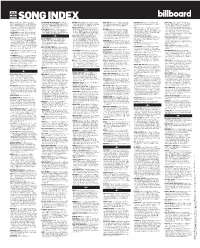

2021 Song Index

FEB 20 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN (Harry Michael BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal DEAR GOD (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ FIRE FOR YOU (SarigSonnet, BMI/Songs Of GOOD DAYS (Solana Imani Rowe Publishing Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By Publishing Deisginee, APRA/Tyron Hapi Publish- Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, Cory Asbury Publishing, ASCAP/SHOUT! MP Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music ing Designee, APRA/BMG Rights Management ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 14 Brio, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI), HL, RO 23 Carter Lang Publishing Designee, BMI/Zuma Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, (Australia) PTY LTD, APRA) RBH 43 BOX OF CHURCHES (Lontrell Williams Publish- CST 50 FIRES (This Little Fire, ASCAP/Songs For FCM, Tuna LLC, BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno AT MY WORST (Artist 101 Publishing Group, ing Designee, ASCAP/Imran Abbas Publishing DE CORA <3 (Warner-Tamerlane Publishing SESAC/Integrity’s Alleluia! Music, SESAC/ Corp., BMI/Ruelas Publishing, ASCAP/Songtrust Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 46 BMI/EMI Pop Music Publishing, GMR/Olney Designee, GEMA/Thomas Kessler Publishing Corp., BMI/Music By Duars Publishing, BMI/ Nordinary Music, SESAC/Capitol CMG Amplifier, Ave, ASCAP/Loshendrix Production, ASCAP/ 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs, GMR/Kehlani Music, ASCAP/These Are Designee, BMI/Slaughter -

Raisin in the Sun Quotations for Writing the Family & The

RAISIN IN THE SUN QUOTATIONS FOR WRITING THE FAMILY & THE AMERICAN DREAM WALTER: DREAMS OF SUCCESS: • Walter talks about the missed business opportunity with Charlie Atkins. P.32 • Complains that he has nothing to pass on to Travis. “I have been married eleven years and I got a boy who sleeps in the livingroom -- and all I got to give him is stories about how rich white people live…” p. 34 • To Mama: “Do you know what this money means to me? Do you know what this money can do for us? Mama—Mama—I want so many things.” P. 73 • Mama: “Son, how come you talk so much ‘bout money?” Walter: “Because, it is life, Mama!” Mama: “Oh—so now its life. Money is life. Once upon a time freedom use to be life—now its money. I guess the world really do change…” Walter: “No—it was always money, Mama. We just didn’t know about it.” p. 74 • “Listen, man, I got some plans that could turn this city upside down. I mean think like he does. Big. Invest big, gamble big, hell, lose big if you have to, you know what I mean. It’s hard to find a man on this whole Southside who understands my kind of thinking—you dig?” p. 84 • Walter to George: “And you—ain’t you bitter, man? Ain’t you just about had it yet? Don’t you see no stars gleaming that you can’t reach out and grab? … Here I am a giant—surrounded by ants. Ants who can’t even understand what it is the giant is talking about” p.85 • Walter to Travis: “Just tell me where you want to go to school and you’ll go. -

URMC V118n83 20091210.Pdf (9.241Mb)

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado COLLEGIAN Volume 118 | No. 8 T D THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 B ASCS ICE, ICE, BABY BOG Leg. a airs director wants student voice on governing board B KIRSTEN SIVEIRA The Rocky ountain Collegian After CSU’s governing board decided to ban concealed weapons on campus, spark- TODAYS IG ing intense controversy student leaders said Wednesday that there must be a student vot- 25 degrees ing member on the board because its mem- bers refuse to listen to students. So far this season, CSU To secure that voting member, Associ- has received a total of 44.2 ated Students of CSU Director of Legislative inches of snow with fi ve full YEAR SEASONA Affairs Matt Worthington drafted a resolu- months of the snow season TOTA IN INCES tion that would allow state leaders to appoint still ahead, according to re- a student to vote on the CSU System Board search from the Department 1 9 9 9 - 2 0 0 0 : 3 . of Governors. The ASCSU Senate moved his of Atmospheric Science. 2 0 0 0 - 2 0 0 1 : 5 resolution to committee Wednesday night. Even if the city receives 2 0 0 1 - 2 0 0 2 : 4 4 .1 ASCSU President Dan Gearhart and CSU- no more snow this winter, 2 0 0 2 - 2 0 0 3 : 1. Pueblo student government President Steve Fort Collins has already re- 2 0 0 3 - 2 0 0 4 : 9 .1 Titus both currently sit on the BOG as non- ceived more snow than in six 2 0 0 4 - 2 0 0 5 : 5 . -

VIRTUAL AXO SONG WORKSHOP May 20, 2020

Want more songs??!! http://axomtm.squarespace.com /songs Contact me anytime! Audra Priluck [email protected] Hey Go Alpha Chi Part one: Hey go Al-pha, hey go Al-pha, hey go Al-pha, hey go Alpha Chi O, go go. Part two: Hey go Alpha Chi Omega go, hey go Alpha Chi Omega go, hey go Alpha Chi Omega go, hey go Alpha Chi O, go go. Follow Us It’s by far the finest thing we’ve ever done. To take the oath and all become as one. Follow us where we go, what we do and who we know. Make it part of you to be a part of us. Sisterhood is what we share and the lyre is what we ear. So join with us for we are Alpha Chi. It’s hard to find the words to tell you how we feel, for it means so much to us, this friendship is so real. It’s Alpha Chi Omega, a smile, a tear, a face, an open heart, an open house, much more than just a place. Follow us where we go, what we do and who we know. Make it part of you to be a part of us. Sisterhood is what we share and the lyre is what we wear, so take the oath and join in Alpha Chi. Pep Smile Pep, smile, You can tell an Alpha Chi by charm, style Guys around will come from miles (Guys around ya all the while) Pep smile charm style, you know the rest Alpha Chi Omega’s the best… ba-da-da Dear Alpha Chi Omega Dear Alpha Chi Omega, I always will treasure, Wherever I wander, you’ll always be home. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Week Ending Friday, March 26, 1999

Week Ending Friday, March 26, 1999 The President's News Conference in the village of Racak back in JanuaryÐin- March 19, 1999 nocent men, women, and children taken from their homes to a gully, forced to kneel Kosovo in the dirt, sprayed with gunfireÐnot be- The President. Ladies and gentlemen, as cause of anything they had done, but because all of you know, we have been involved in of who they were. an intensive effort to end the conflict in Now, roughly 40,000 Serbian troops and Kosovo for many weeks now. With our police are massing in and around Kosovo. NATO allies and with Russia, we proposed Our firmness is the only thing standing be- a peace agreement to stop the killing and tween them and countless more villages like give the people of Kosovo the self-deter- RacakÐfull of people without protection, mination and government they need and to even though they have now chosen peace. which they are entitled under the constitu- Make no mistake, if we and our allies do tion of their government. not have the will to act, there will be more Yesterday the Kosovar Albanians signed massacres. In dealing with aggressors in the that agreement. Even though they have not Balkans, hesitation is a license to kill. But obtained all they seek, even as their people action and resolve can stop armies and save remain under attack, they've had the vision lives. to see that a just peace is better than an We must also understand our stake in unwinnable war. Now only President peace in the Balkans and in Kosovo. -

Pipes 1 PJ Pipes Professor Peter Fields English Comp 105 6 February 2018 Chances of Rap Being All We Got We All Are Bo

Pipes 1 PJ Pipes Professor Peter Fields English Comp 105 6 February 2018 Chances of Rap being All We Got We all are born in different circumstances to deal with in our life. These circumstances can depend on in some countries the class you’re born into, the city you grew up in, or just challenges in life that pop up. With some people they have ways to coop with the stress, violence around their town, parents getting divorced, etc. In some instances they are able to jump out of their class system, even make out of the horrific terror that surrounds them. In Chance The Rapper’s song All We Got, with featured on it his idol Kanye West, he speaks the troubles he faced being an inner city kid from Chicago. While everything around him was a distraction music made it able for him not only better himself but for his family as well. Chance is an up and coming rapper from Chicago. Even though now most people wouldn’t consider him still on the come up, but with only a few mix tapes and one album he is still relatively new to the music world. Chance is not the typical rapper because he raps a lot of not only his family but also his spiritual connection with God. A lot of songs of deeper meaning than most other artist’s songs have. The slow steady beat mixed in with the bass and his dramatic emphasis or slow down on phrases make him a fantastic artist to listen to. -

The Sounds of Liberation: Resistance, Cultural Retention, and Progressive Traditions for Social Justice in African American Music

THE SOUNDS OF LIBERATION: RESISTANCE, CULTURAL RETENTION, AND PROGRESSIVE TRADITIONS FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE IN AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies by Luqman Muhammad Abdullah May 2009 © 2009 Luqman Muhammad Abdullah ABSTRACT The cultural production of music in the Black community has traditionally operated as much more than a source of entertainment. In fact, my thesis illustrates how progressive traditions for social justice in Black music have acted as a source of agency and a tool for resistance against oppression. This study also explains how the music of African Americans has served as a primary mechanism for disseminating their cultural legacy. I have selected four Black artists who exhibit the aforementioned principles in their musical production. Bernice Johnson Reagon, John Coltrane, Curtis Mayfield and Gil Scott-Heron comprise the talented cadre of musicians that exemplify the progressive Black musical tradition for social justice in their respective genres of gospel, jazz, soul and spoken word. The methods utilized for my study include a socio-historical account of the origins of Black music, an overview of the artists’ careers, and a lyrical analysis of selected songs created by each of the artists. This study will contribute to the body of literature surrounding the progressive roles, functions and utilities of African American music. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH My mother garners the nickname “gypsy” from her siblings due to the fact that she is always moving and relocating to new and different places. -

Abstract Humanities Jordan Iii, Augustus W. B.S. Florida

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES JORDAN III, AUGUSTUS W. B.S. FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY, 1994 M.A. CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, 1998 THE IDEOLOGICAL AND NARRATIVE STRUCTURES OF HIP-HOP MUSIC: A STUDY OF SELECTED HIP-HOP ARTISTS Advisor: Dr. Viktor Osinubi Dissertation Dated May 2009 This study examined the discourse of selected Hip-Hop artists and the biographical aspects of the works. The study was based on the structuralist theory of Roland Barthes which claims that many times a performer’s life experiences with class struggle are directly reflected in his artistic works. Since rap music is a counter-culture invention which was started by minorities in the South Bronx borough ofNew York over dissatisfaction with their community, it is a cultural phenomenon that fits into the category of economic and political class struggle. The study recorded and interpreted the lyrics of New York artists Shawn Carter (Jay Z), Nasir Jones (Nas), and southern artists Clifford Harris II (T.I.) and Wesley Weston (Lii’ Flip). The artists were selected on the basis of geographical spread and diversity. Although Hip-Hop was again founded in New York City, it has now spread to other parts of the United States and worldwide. The study investigated the biography of the artists to illuminate their struggles with poverty, family dysfunction, aggression, and intimidation. 1 The artists were found to engage in lyrical battles; therefore, their competitive discourses were analyzed in specific Hip-Hop selections to investigate their claims of authorship, imitation, and authenticity, including their use of sexual discourse and artistic rivalry, to gain competitive advantage. -

TAASA -This Is America Song Lyrics

Song #1 Nina Simone by Four Women My skin is black My arms are long My hair is woolly My back is strong Strong enough to take the pain Inflicted again and again What do they call me? My name is Aunt Sarah My name is Aunt Sarah Aunt Sarah My skin is yellow My hair is long Between two worlds I do belong But my father was rich and white He forced my mother late one night And what do they call me? My name is Saffronia My name is Saffronia My skin is tan My hair is fine My hips invite you My mouth like wine Whose little girl am I? Anyone who has money to buy What do they call me? My name is Sweet Thing My name is Sweet Thing My skin is brown My manner is tough I'll kill the first mother I see! My life has been rough I'm awfully bitter these days Because my parents were slaves What do they call me? My name is Peaches! Song #2 Aretha Franklin [Written by Otis Redding] What you want, baby, I got it What you need, do you know I got it? All I'm askin' is for a little respect when you get home (Just a little bit) Hey baby (Just a little bit) when you get home (Just a little bit) mister (Just a little bit) I ain't gonna do you wrong while you're gone Ain't gon' do you wrong 'cause I don't wanna All I'm askin' is for a little respect when you come home (Just a little bit) Baby (Just a little bit) When you get home (Just a little bit) Yeah (Just a little bit) I'm about to give you all of my money And all I'm askin' in return, honey Is to give me my propers when you get home (Just a, just a, just a, just a) Yeah, baby (Just a, just a, just a, just a) When