Oral History Interview with Howard Finster, 1984 June 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2014 Newsletter of Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory Number 45 the PRIMARY SOURCE

Spring/Summer 2014 Newsletter of Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory Number 45 THE PRIMARY SOURCE Our mission is to conserve birds and their habitats. RMBO Leads Landmark Meeting in Costa Rica By Teddy Parker-Renga to breeding, threats to non-breeding and it’s important for RMBO and partners to Communications Manager population trend) using the Partners In support and advance conservation abroad, In March, Rocky Mountain Bird Flight species assessment process. Scores he said. Observatory spearheaded the first-ever ranged from 1 (low vulnerability) to 5 Next steps include developing com- conservation assessment of the birds of (high vulnerability) for each factor, with munication tools and messages to engage Central America. a higher overall score indicating a greater stakeholders in conserving at-risk species. At the meeting held in San Vito, Costa vulnerability to population decline or Thank you to all of the partners who Rica, 30 participants representing the extinction. attended the meeting and Environment seven Central American countries, Mexico International Director Arvind Panjabi Canada, Missouri Department of Conser- and the U.S. assessed all 407 bird species said partners who attended the meeting vation and USGS for funding. unique to Central America, as well as 500- saw tremendous value in the process as View photos from the meeting and the plus species shared between Mexico and a way to establish conservation priori- amazing species we saw birding in Costa Central America. This included landbirds, ties for birds and habitat in their own Rica at www.facebook.com/RMBObirds. shorebirds, waterbirds and waterfowl. countries. Since many bird species that To learn more about the Partners In During the assessment, birds were breed in the Rockies and elsewhere in the Flight species assessment process, visit http:// assigned scores for three factors (threats western U.S. -

American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection the Fine Arts Center Is an Accredited Member of the American Alliance of Museums

Strange and Wonderful American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection The Fine Arts Center is an accredited member of the American Alliance of Museums. We are proud to be in the company of the most prestigious institutions in the country carrying this important designation and to have been among the first group of 16 museums The Fine Arts Center is an accredited member of the American Alliance of Museums. We are proud to be in the company of the most accredited by the AAM in 1971. prestigious institutions in the country carrying this important designation and to have been among the first group of 16 museums accredited by the AAM in 1971. Copyright© 2013 Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Copyright © 2013 Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Strange and Wonderful: American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection. Authors: Steve Glueckert; Tom Patterson Charles Bunnell: Rocky Mountain Modern. Authors: Cori Sherman North and Blake Milteer. Editor: Amberle Sherman. ISBN 978-0-916537-16-6 Published on the occasion of the exhibition Strange and Wonderful: American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection at the Missoula Art 978-0-916537-15-9 Museum, September 22 – December 22, 2013 and the Colorado Spring Fine Arts Center, February 8 - May 18, 2014 Published on the occasion of the exhibition Charles Bunnell: Rocky Mountain Modern at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Printed by My Favorite Printer June 8 – Sept. 15, 2013 Projected Directed and Curated by Sam Gappmayer Printed by My Favorite Printer Photography for all plates by Tom Ferris. -

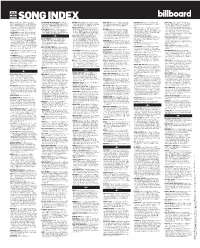

2021 Song Index

FEB 20 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN (Harry Michael BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal DEAR GOD (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ FIRE FOR YOU (SarigSonnet, BMI/Songs Of GOOD DAYS (Solana Imani Rowe Publishing Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By Publishing Deisginee, APRA/Tyron Hapi Publish- Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, Cory Asbury Publishing, ASCAP/SHOUT! MP Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music ing Designee, APRA/BMG Rights Management ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 14 Brio, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI), HL, RO 23 Carter Lang Publishing Designee, BMI/Zuma Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, (Australia) PTY LTD, APRA) RBH 43 BOX OF CHURCHES (Lontrell Williams Publish- CST 50 FIRES (This Little Fire, ASCAP/Songs For FCM, Tuna LLC, BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno AT MY WORST (Artist 101 Publishing Group, ing Designee, ASCAP/Imran Abbas Publishing DE CORA <3 (Warner-Tamerlane Publishing SESAC/Integrity’s Alleluia! Music, SESAC/ Corp., BMI/Ruelas Publishing, ASCAP/Songtrust Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 46 BMI/EMI Pop Music Publishing, GMR/Olney Designee, GEMA/Thomas Kessler Publishing Corp., BMI/Music By Duars Publishing, BMI/ Nordinary Music, SESAC/Capitol CMG Amplifier, Ave, ASCAP/Loshendrix Production, ASCAP/ 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs, GMR/Kehlani Music, ASCAP/These Are Designee, BMI/Slaughter -

Raisin in the Sun Quotations for Writing the Family & The

RAISIN IN THE SUN QUOTATIONS FOR WRITING THE FAMILY & THE AMERICAN DREAM WALTER: DREAMS OF SUCCESS: • Walter talks about the missed business opportunity with Charlie Atkins. P.32 • Complains that he has nothing to pass on to Travis. “I have been married eleven years and I got a boy who sleeps in the livingroom -- and all I got to give him is stories about how rich white people live…” p. 34 • To Mama: “Do you know what this money means to me? Do you know what this money can do for us? Mama—Mama—I want so many things.” P. 73 • Mama: “Son, how come you talk so much ‘bout money?” Walter: “Because, it is life, Mama!” Mama: “Oh—so now its life. Money is life. Once upon a time freedom use to be life—now its money. I guess the world really do change…” Walter: “No—it was always money, Mama. We just didn’t know about it.” p. 74 • “Listen, man, I got some plans that could turn this city upside down. I mean think like he does. Big. Invest big, gamble big, hell, lose big if you have to, you know what I mean. It’s hard to find a man on this whole Southside who understands my kind of thinking—you dig?” p. 84 • Walter to George: “And you—ain’t you bitter, man? Ain’t you just about had it yet? Don’t you see no stars gleaming that you can’t reach out and grab? … Here I am a giant—surrounded by ants. Ants who can’t even understand what it is the giant is talking about” p.85 • Walter to Travis: “Just tell me where you want to go to school and you’ll go. -

URMC V118n83 20091210.Pdf (9.241Mb)

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado COLLEGIAN Volume 118 | No. 8 T D THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 B ASCS ICE, ICE, BABY BOG Leg. a airs director wants student voice on governing board B KIRSTEN SIVEIRA The Rocky ountain Collegian After CSU’s governing board decided to ban concealed weapons on campus, spark- TODAYS IG ing intense controversy student leaders said Wednesday that there must be a student vot- 25 degrees ing member on the board because its mem- bers refuse to listen to students. So far this season, CSU To secure that voting member, Associ- has received a total of 44.2 ated Students of CSU Director of Legislative inches of snow with fi ve full YEAR SEASONA Affairs Matt Worthington drafted a resolu- months of the snow season TOTA IN INCES tion that would allow state leaders to appoint still ahead, according to re- a student to vote on the CSU System Board search from the Department 1 9 9 9 - 2 0 0 0 : 3 . of Governors. The ASCSU Senate moved his of Atmospheric Science. 2 0 0 0 - 2 0 0 1 : 5 resolution to committee Wednesday night. Even if the city receives 2 0 0 1 - 2 0 0 2 : 4 4 .1 ASCSU President Dan Gearhart and CSU- no more snow this winter, 2 0 0 2 - 2 0 0 3 : 1. Pueblo student government President Steve Fort Collins has already re- 2 0 0 3 - 2 0 0 4 : 9 .1 Titus both currently sit on the BOG as non- ceived more snow than in six 2 0 0 4 - 2 0 0 5 : 5 . -

VIRTUAL AXO SONG WORKSHOP May 20, 2020

Want more songs??!! http://axomtm.squarespace.com /songs Contact me anytime! Audra Priluck [email protected] Hey Go Alpha Chi Part one: Hey go Al-pha, hey go Al-pha, hey go Al-pha, hey go Alpha Chi O, go go. Part two: Hey go Alpha Chi Omega go, hey go Alpha Chi Omega go, hey go Alpha Chi Omega go, hey go Alpha Chi O, go go. Follow Us It’s by far the finest thing we’ve ever done. To take the oath and all become as one. Follow us where we go, what we do and who we know. Make it part of you to be a part of us. Sisterhood is what we share and the lyre is what we ear. So join with us for we are Alpha Chi. It’s hard to find the words to tell you how we feel, for it means so much to us, this friendship is so real. It’s Alpha Chi Omega, a smile, a tear, a face, an open heart, an open house, much more than just a place. Follow us where we go, what we do and who we know. Make it part of you to be a part of us. Sisterhood is what we share and the lyre is what we wear, so take the oath and join in Alpha Chi. Pep Smile Pep, smile, You can tell an Alpha Chi by charm, style Guys around will come from miles (Guys around ya all the while) Pep smile charm style, you know the rest Alpha Chi Omega’s the best… ba-da-da Dear Alpha Chi Omega Dear Alpha Chi Omega, I always will treasure, Wherever I wander, you’ll always be home. -

Het Verhaal Van De 340 Songs Inhoud

Philippe Margotin en Jean-Michel Guesdon Rollingthe Stones compleet HET VERHAAL VAN DE 340 SONGS INHOUD 6 _ Voorwoord 8 _ De geboorte van een band 13 _ Ian Stewart, de zesde Stone 14 _ Come On / I Want To Be Loved 18 _ Andrew Loog Oldham, uitvinder van The Rolling Stones 20 _ I Wanna Be Your Man / Stoned EP DATUM UITGEBRACHT ALBUM Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down The Road Apiece ALBUM DATUM UITGEBRACHT 10 januari 1964 EP Everybody Needs Somebody To Love Under The Boardwalk DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : (er zijn ook andere data, zoals DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : 17 april 1964 16, 17 of 18 januari genoemd Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down Home Girl I Can’t Be Satisfi ed 15 januari 1965 Label Decca als datum van uitbrengen) 14 augustus 1964 You Can’t Catch Me Pain In My Heart Label Decca REF : LK 4605 Label Decca Label Decca Time Is On My Side Off The Hook REF : LK 4661 12 weken op nummer 1 REF : DFE 8560 REF : DFE 8590 10 weken op nummer 1 What A Shame Susie Q Grown Up Wrong TH TH TH ROING (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 FIVE I Just Want To Make Love To You Honest I Do ROING ROING I Need You Baby (Mona) Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) Little By Little H ROLLIN TONS NOW VRNIGD TATEN EBRUARI 965) I’m A King Bee Everybody Needs Somebody To Love / Down Home Girl / You Can’t Catch Me / Heart Of Stone / What A Shame / I Need You Baby (Mona) / Down The Road Carol Apiece / Off The Hook / Pain In My Heart / Oh Baby (We Got A Good Thing SONS Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) If You Need Me Goin’) / Little Red Rooster / Surprise, Surprise. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Week Ending Friday, March 26, 1999

Week Ending Friday, March 26, 1999 The President's News Conference in the village of Racak back in JanuaryÐin- March 19, 1999 nocent men, women, and children taken from their homes to a gully, forced to kneel Kosovo in the dirt, sprayed with gunfireÐnot be- The President. Ladies and gentlemen, as cause of anything they had done, but because all of you know, we have been involved in of who they were. an intensive effort to end the conflict in Now, roughly 40,000 Serbian troops and Kosovo for many weeks now. With our police are massing in and around Kosovo. NATO allies and with Russia, we proposed Our firmness is the only thing standing be- a peace agreement to stop the killing and tween them and countless more villages like give the people of Kosovo the self-deter- RacakÐfull of people without protection, mination and government they need and to even though they have now chosen peace. which they are entitled under the constitu- Make no mistake, if we and our allies do tion of their government. not have the will to act, there will be more Yesterday the Kosovar Albanians signed massacres. In dealing with aggressors in the that agreement. Even though they have not Balkans, hesitation is a license to kill. But obtained all they seek, even as their people action and resolve can stop armies and save remain under attack, they've had the vision lives. to see that a just peace is better than an We must also understand our stake in unwinnable war. Now only President peace in the Balkans and in Kosovo. -

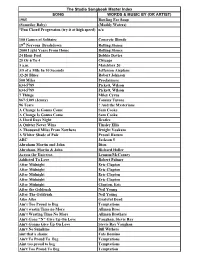

Copy of Songbook Master Index for Website

The Studio Songbook Master Index SONG WORDS & MUSIC BY (OR ARTIST) 1985 Bowling For Soup (Someday Baby) (Muddy Waters) *Fun Chord Progression (try it at high speed) n/a 100 Games of Solitaire Concrete Blonde 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 2000 Light Years From Home Rolling Stones 24 Hour Fool Debbie Davies 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 3/5 of a Mile In 10 Seconds Jefferson Airplane 32-20 Blues Robert Johnson 500 Miles Proclaimers 634-5789 Pickett, Wilson 634-5789 Pickett, Wilson 7 Things Miley Cyrus 867-5309 (Jenny) Tommy Tutone 96 Tears ? And the Mysterians A Change Is Gonna Come Sam Cooke A Change Is Gonna Come Sam Cooke A Hard Days Night Beatles A Quitter Never Wins Tinsley Ellis A Thousand Miles From Nowhere Dwight Yoakam A Whiter Shade of Pale Procul Harum ABC Jackson 5 Abraham Martin and John Dion Abraham, Martin & John Richard Holler Across the Universe. Lennon/McCarney Addicted To Love Robert Palmer After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Clapton, Eric After the Goldrush Neil Young After The Goldrush Neil Young Aiko Aiko Grateful Dead Ain’t Too Proud to Beg Temptations Ain’t wastin Time no More Allman Bros Ain’t Wasting Time No More Allman Brothers Ain't Gone "N" Give Up On Love Vaughan, Stevie Ray Ain't Gonna Give Up On Love Stevie Ray Vaughan Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers aint that a shame Fats Domino Ain't To Proud To Beg Temptations Aint too proud to beg Temptations Ain't Too Proud To Beg Temptation Ain't Too Proud to Beg -

The Rolling Stones Complete Recording Sessions 1962 - 2020 Martin Elliott Session Tracks Appendix

THE ROLLING STONES COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1962 - 2020 MARTIN ELLIOTT SESSION TRACKS APPENDIX * Not Officially Released Tracks Tracks in brackets are rumoured track names. The end number in brackets is where to find the entry in the 2012 book where it has changed. 1962 January - March 1962 Bexleyheath, Kent, England. S0001. Around And Around (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (1.21) * S0002. Little Queenie (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (4.32) * (a) Alternative Take (4.11) S0003. Beautiful Delilah (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.58) * (a) Alternative Take (2.18) S0004. La Bamba (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (0.18) * S0005. Go On To School (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.02) * S0006. I'm Left, You're Right, She's Gone (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.31) * S0007. Down The Road Apiece (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.12) * S0008. Don't Stay Out All Night (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.30) * S0009. I Ain't Got You (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.00) * S0010. Johnny B. Goode (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.24) * S0011. Reelin' And A Rockin' (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) * S0012. Bright Lights, Big City (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) * 27 October 1962 Curly Clayton Sound Studios, Highbury, London, England. S0013. You Can't Judge A Book By The Cover (0.36) * S0014. Soon Forgotten * S0015. Close Together * 1963 11 March 1963 IBC Studios, London, England. S0016. Diddley Daddy (2.38) S0017. Road Runner (3.04) S0018. I Want To Be Loved I (2.02) S0019. -

GAYBY Written by Jonathan Lisecki

GAYBY Written by Jonathan Lisecki Transcription 8/14/12 C/o! Washington Square Arts, 310 Bowery, 2nd Floor, New York, NY, 10012, 212.253.0333 x22, [email protected] 1 01:00:14:00 !She looks just like you 2 01:00:15:16 Kind of, right? 3 01:00:16:30 !Sure... in the cheekbones. 4 01:00:19:15 Shut up. 5 01:00:20:15 No, she's perfect. 6 01:00:22:03 Isn't she? It better go through. 7 01:00:24:15 It will. The adoption people are gonna love you. 8 01:00:33:13 So, what do you wanna do? 9 01:00:36:00 Well, this is nice. What we’re doing. We could talk. I like talking. 10 01:00:39:14 Yeah, I’m not that big on talking. 11 01:00:43:15 Right. 12 01:00:44:09 And, I’m not that into nice. 13 01:00:47:00 Right. 14 01:00:48:17 Wow, I just never thought you'd be the first one to have a kid. 15 01:00:52:03 Why? Cause I'm barren? 16 01:00:53:16 Are you ever gonna let that go? I said that like three years ago. 17 01:00:56:00 Loudly. At my birthday party. 18 01:00:58:08 I just thought it was the correct term. 19 01:01:08:00 I meant that when we were younger you never wanted to have kids and I always did. 20 01:01:12:10 !You'd have to date a guy longer then five minutes if you wanna have a kid with one.