EE320L Electronics I Laboratory Laboratory Exercise #8 Amplifiers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPERIMENT 4: RC, RL and RD Circuits

Laboratory 4: The RC Circuit EXPERIMENT 4: RC, RL and RD CIRCUITs Equipment List An assortment of resistor, one each of (330, 1k,1.5k, 10k,100k,1000k) Function Generator Oscilloscope 0.F Ceramic Capacitor 100H Inductor LED and 1N4001 Diode. Introduction We have studied D.C. circuits with resistors and batteries and discovered that Ohm’s Law governs the relationship between current through and voltage across a resistance. It is a linear response; i.e., 푉 = 퐼푅 (1) Such circuit elements are called passive elements. With A.C. circuits we find other passive elements called capacitors and inductors. These, too, obey Ohm’s Law and circuit loop problems can be solved using Kirchoff’ 3 Laws in much the same way as with DC. circuits. However, there is one major difference - in an AC. circuit, voltage across and current through a circuit element or branch are not necessarily in phase with one another. We saw an example of this at the end of Experiment 3. In an AC. series circuit the source voltage and current are time dependent such that 푖(푡) = 푖푠sin(휔푡) (2) 푣(푡) = 푣푠sin(휔푡 + 휙) where, in this case, voltage leads current by the phase angle , and Vs and Is are the peak source voltage and peak current, respectively. As you know or will learn from the text, the phase relationships between circuit element voltages and series current are these: resistor - voltage and current are in phase implying that 휙 = 0 휋 capacitor - voltage lags current by 90o implying that 휙 = − 2 inductor - voltage leads current by 90o implying that 휙 = 휋/2 Laboratory 4: The RC Circuit In this experiment we will study a circuit with a resistor and a capacitor in m. -

Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers

Chapter 7: Transistors, part 2 Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers The transistor amplifiers that we studied in the last chapter have some serious problems for use in AC signals. Their most serious shortcoming is that there is a “dead region” where small signals do not turn on the transistor. So, if your signal is smaller than 0.6 V, or if it is negative, the transistor does not conduct and the amplifier does not work. Design goals for an AC amplifier Before moving on to making a better AC amplifier, let’s define some useful terms. We define the output range to be the range of possible output voltages. We refer to the maximum and minimum output voltages as the rail voltages and the output swing is the difference between the rail voltages. The input range is the range of input voltages that produce outputs which are not at either rail voltage. Our goal in designing an AC amplifier is to get an input range and output range which is symmetric around zero and ensure that there is not a dead region. To do this we need make sure that the transistor is in conduction for all of our input range. How does this work? We do it by adding an offset voltage to the input to make sure the voltage presented to the transistor’s base with no input signal, the resting or quiescent voltage , is well above ground. In lab 6, the function generator provided the offset, in this chapter we will show how to design an amplifier which provides its own offset. -

Unit-1 Mphycc-7 Ujt

UNIT-1 MPHYCC-7 UJT The Unijunction Transistor or UJT for short, is another solid state three terminal device that can be used in gate pulse, timing circuits and trigger generator applications to switch and control either thyristors and triac’s for AC power control type applications. Like diodes, unijunction transistors are constructed from separate P-type and N-type semiconductor materials forming a single (hence its name Uni-Junction) PN-junction within the main conducting N-type channel of the device. Although the Unijunction Transistor has the name of a transistor, its switching characteristics are very different from those of a conventional bipolar or field effect transistor as it can not be used to amplify a signal but instead is used as a ON-OFF switching transistor. UJT’s have unidirectional conductivity and negative impedance characteristics acting more like a variable voltage divider during breakdown. Like N-channel FET’s, the UJT consists of a single solid piece of N-type semiconductor material forming the main current carrying channel with its two outer connections marked as Base 2 ( B2 ) and Base 1 ( B1 ). The third connection, confusingly marked as the Emitter ( E ) is located along the channel. The emitter terminal is represented by an arrow pointing from the P-type emitter to the N-type base. The Emitter rectifying p-n junction of the unijunction transistor is formed by fusing the P-type material into the N-type silicon channel. However, P-channel UJT’s with an N- type Emitter terminal are also available but these are little used. -

PH-218 Lec-12: Frequency Response of BJT Amplifiers

Analog & Digital Electronics Course No: PH-218 Lec-12: Frequency Response of BJT Amplifiers Course Instructors: Dr. A. P. VAJPEYI Department of Physics, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, India 1 High frequency Response of CE Amplifier At high frequencies, internal transistor junction capacitances do come into play, reducing an amplifier's gain and introducing phase shift as the signal frequency increases. In BJT, C be is the B-E junction capacitance, and C bc is the B-C junction capacitance. (output to input capacitance) At lower frequencies, the internal capacitances have a very high reactance because of their low capacitance value (usually only a few pf) and the low frequency value. Therefore, they look like opens and have no effect on the transistor's performance. As the frequency goes up, the internal capacitive reactance's go down, and at some point they begin to have a significant effect on the transistor's gain. High frequency Response of CE Amplifier When the reactance of C be becomes small enough, a significant amount of the signal voltage is lost due to a voltage-divider effect of the source resistance and the reactance of C be . When the reactance of Cbc becomes small enough, a significant amount of output signal voltage is fed back out of phase with the input (negative feedback), thus effectively reducing the voltage gain. 3 Millers Theorem The Miller effect occurs only in inverting amplifiers –it is the inverting gain that magnifies the feedback capacitance. vin − (−Av in ) iin = = vin 1( + A)× 2π × f ×CF X C Here C F represents C bc vin 1 1 Zin = = = iin 1( + A)× 2π × f ×CF 2π × f ×Cin 1( ) Cin = + A ×CF 4 High frequency Response of CE Amp.: Millers Theorem Miller's theorem is used to simplify the analysis of inverting amplifiers at high-frequencies where the internal transistor capacitances are important. -

KVL Example Resistor Voltage Divider • Consider a Series of Resistors And

KVL Example Resistor Voltage Divider • Consider a series of resistors and a voltage source • Then using KVL V −V1 −V2 = 0 • Since by Ohm’s law V1 = I1R1 V2 = I1R2 • Then V − I1R1 − I1R2 = V − I1()R1 + R2 = 0 • Thus V 5 I1 = = = 1 mA R1 + R2 2000 + 3000 • i.e. get the resistors in series formula Rtotal = R1 + R2 = 5 KΩ KVL Example Resistor Voltage Divider Continued • What is the voltage across each resistor • Now we can relate V1 and V2 to the applied V • With the substitution V I 1 = R1 + R 2 • Thus V1 VR1 5(2000) V1 = I1R1 = = = 2 V R1 + R2 2000 + 3000 • Similarly for the V2 VR2 5(3000) V1 = I1R2 = = = 3V R1 + R2 2000 + 3000 General Resistor Voltage Divider • Consider a long series of resistors and a voltage source • Then using KVL or series resistance get N V V = I1∑ R j KorKI1 = N j=1 ∑ R j j=1 • The general voltage Vk across resistor Rk is VRk Vk = I1Rk = N ∑ R j j=1 • Note important assumption: current is the same in all Rj Usefulness of Resistor Voltage Divider • A voltage divider can generate several voltages from a fixed source • Common circuits (eg IC’s) have one supply voltage • Use voltage dividers to create other values at low cost/complexity • Eg. Need different supply voltages for many transistors • Eg. Common computer outputs 5V (called TTL) • But modern chips (CMOS) are lower voltage (eg. 2.5 or 1.8V) • Quick interface – use a voltage divider on computer output • Gives desired input to the chip Variable Voltage and Resistor Voltage Divider • If have one fixed and one variable resistor (rheostat) • Changing variable resistor controls out Voltage across rheostat • Simple power supplies use this • Warning: ideally no additional loads can be applied. -

Common Drain - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 10-5-17 下午7:07

Common drain - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 10-5-17 下午7:07 Common drain From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In electronics, a common-drain amplifier, also known as a source follower, is one of three basic single- stage field effect transistor (FET) amplifier topologies, typically used as a voltage buffer. In this circuit the gate terminal of the transistor serves as the input, the source is the output, and the drain is common to both (input and output), hence its name. The analogous bipolar junction transistor circuit is the common- collector amplifier. In addition, this circuit is used to transform impedances. For example, the Thévenin resistance of a combination of a voltage follower driven by a voltage source with high Thévenin resistance is reduced to only the output resistance of the voltage follower, a small resistance. That resistance reduction makes the combination a more ideal voltage source. Conversely, a voltage follower inserted between a small load resistance and a driving stage presents an infinite load to the driving stage, an advantage in coupling a voltage signal to a small load. Characteristics At low frequencies, the source follower pictured at right has the following small signal characteristics.[1] Voltage gain: Current gain: Input impedance: Basic N-channel JFET source Output impedance: (the parallel notation indicates the impedance follower circuit (neglecting of components A and B that are connected in parallel) biasing details). The variable gm that is not listed in Figure 1 is the transconductance of the device (usually given in units of siemens). References http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_drain Page 1 of 2 Common drain - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 10-5-17 下午7:07 1. -

Cascode Amplifiers by Dennis L. Feucht Two-Transistor Combinations

Cascode Amplifiers by Dennis L. Feucht Two-transistor combinations, such as the Darlington configuration, provide advantages over single-transistor amplifier stages. Another two-transistor combination in the analog designer's circuit library combines a common-emitter (CE) input configuration with a common-base (CB) output. This article presents the design equations for the basic cascode amplifier and then offers other useful variations. (FETs instead of BJTs can also be used to form cascode amplifiers.) Together, the two transistors overcome some of the performance limitations of either the CE or CB configurations. Basic Cascode Stage The basic cascode amplifier consists of an input common-emitter (CE) configuration driving an output common-base (CB), as shown above. The voltage gain is, by the transresistance method, the ratio of the resistance across which the output voltage is developed by the common input-output loop current over the resistance across which the input voltage generates that current, modified by the α current losses in the transistors: v R A = out = −α ⋅α ⋅ L v 1 2 β + + + vin RB /( 1 1) re1 RE where re1 is Q1 dynamic emitter resistance. This gain is identical for a CE amplifier except for the additional α2 loss of Q2. The advantage of the cascode is that when the output resistance, ro, of Q2 is included, the CB incremental output resistance is higher than for the CE. For a bipolar junction transistor (BJT), this may be insignificant at low frequencies. The CB isolates the collector-base capacitance, Cbc (or Cµ of the hybrid-π BJT model), from the input by returning it to a dynamic ground at VB. -

Ohm's Law and Kirchhoff's Laws

CHAPTER 2 Basic Laws Here we explore two fundamental laws that govern electric circuits (Ohm's law and Kirchhoff's laws) and discuss some techniques commonly applied in circuit design and analysis. 2.1. Ohm's Law Ohm's law shows a relationship between voltage and current of a resis- tive element such as conducting wire or light bulb. 2.1.1. Ohm's Law: The voltage v across a resistor is directly propor- tional to the current i flowing through the resistor. v = iR; where R = resistance of the resistor, denoting its ability to resist the flow of electric current. The resistance is measured in ohms (Ω). • To apply Ohm's law, the direction of current i and the polarity of voltage v must conform with the passive sign convention. This im- plies that current flows from a higher potential to a lower potential 15 16 2. BASIC LAWS in order for v = iR. If current flows from a lower potential to a higher potential, v = −iR. l i + v R – Material with Cross-sectional resistivity r area A 2.1.2. The resistance R of a cylindrical conductor of cross-sectional area A, length L, and conductivity σ is given by L R = : σA Alternatively, L R = ρ A where ρ is known as the resistivity of the material in ohm-meters. Good conductors, such as copper and aluminum, have low resistivities, while insulators, such as mica and paper, have high resistivities. 2.1.3. Remarks: (a) R = v=i (b) Conductance : 1 i G = = R v 1 2 The unit of G is the mho (f) or siemens (S) 1Yes, this is NOT a typo! It was derived from spelling ohm backwards. -

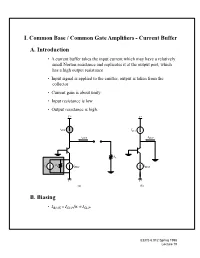

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers - Current Buffer A. Introduction • A current buffer takes the input current which may have a relatively small Norton resistance and replicates it at the output port, which has a high output resistance • Input signal is applied to the emitter, output is taken from the collector • Current gain is about unity • Input resistance is low • Output resistance is high. V+ V+ i SUP ISUP iOUT IOUT RL R is S IBIAS IBIAS V− V− (a) (b) B. Biasing = /α ≈ • IBIAS ISUP ISUP EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 II. Small Signal Two Port Parameters A. Common Base Current Gain Ai • Small-signal circuit; apply test current and measure the short circuit output current ib iout + = β v r gmv oib r − o ve roc it • Analysis -- see Chapter 8, pp. 507-509. • Result: –β ---------------o ≅ Ai = β – 1 1 + o • Intuition: iout = ic = (- ie- ib ) = -it - ib and ib is small EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 B. Common Base Input Resistance Ri • Apply test current, with load resistor RL present at the output + v r gmv r − o roc RL + vt i − t • See pages 509-510 and note that the transconductance generator dominates which yields 1 Ri = ------ gm µ • A typical transconductance is around 4 mS, with IC = 100 A • Typical input resistance is 250 Ω -- very small, as desired for a current amplifier • Ri can be designed arbitrarily small, at the price of current (power dissipation) EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 C. Common-Base Output Resistance Ro • Apply test current with source resistance of input current source in place • Note roc as is in parallel with rest of circuit g v m ro + vt it r − oc − v r RS + • Analysis is on pp. -

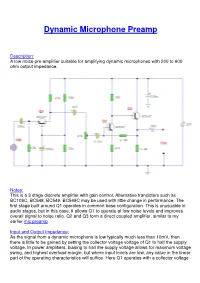

Dynamic Microphone Amplifier

Dynamic Microphone Preamp Description: A low noise pre-amplifier suitable for amplifying dynamic microphones with 200 to 600 ohm output impedance. Notes: This is a 3 stage discrete amplifier with gain control. Alternative transistors such as BC109C, BC548, BC549, BC549C may be used with little change in performance. The first stage built around Q1 operates in common base configuration. This is unusuable in audio stages, but in this case, it allows Q1 to operate at low noise levels and improves overall signal to noise ratio. Q2 and Q3 form a direct coupled amplifier, similar to my earlier mic preamp . Input and Output Impedance: As the signal from a dynamic microphone is low typically much less than 10mV, then there is little to be gained by setting the collector voltage voltage of Q1 to half the supply voltage. In power amplifiers, biasing to half the supply voltage allows for maximum voltage swing, and highest overload margin, but where input levels are low, any value in the linear part of the operating characteristics will suffice. Here Q1 operates with a collector voltage of 2.4V and a low collector current of around 200uA. This low collector current ensures low noise performance and also raises the input impedance of the stage to around 400 ohms. This is a good match for any dynamic microphone having an impedances between 200 and 600 ohms. The output impedance at Q3 is low, the graph of input and output impedance versus frequency is shown below: Gain and Frequency Response: The overall gain of this pre-amplifier is around +39dB or about 90 times. -

Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response.Pptx

EE105 – Fall 2014 Microelectronic Devices and Circuits Prof. Ming C. Wu [email protected] 511 Sutardja Dai Hall (SDH) Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 1 Common-Emitter Amplifier – ωH Open-Circuit Time Constant (OCTC) Method At high frequencies, impedances of coupling and bypass capacitors are small enough to be considered short circuits. Open-circuit time constants associated with impedances of device capacitances are considered instead. 1 ωH ≅ m ∑RioCi i=1 where Rio is resistance at terminals of ith capacitor C with all other v ! R $ i R = x = r #1+ g R + L & capacitors open-circuited. µ 0 π 0 m L ix " rπ 0 % For a C-E amplifier, assuming C = 0 L 1 1 ωH ≅ = Rπ 0 = rπ 0 Rπ 0Cπ + Rµ 0Cµ rπ 0CT Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 2 1 Common-Emitter Amplifier High Frequency Response - Miller Effect • First, find the simplified small -signal model of the C-E amp. • Replace coupling and bypass capacitors with short circuits • Insert the high frequency small -signal model for the transistor ! # rπ 0 = rπ "rx +(RB RI )$ Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 3 Common-Emitter Amplifier – ωH High Frequency Response - Miller Effect (cont.) v R r Input gain is found as A = b = in ⋅ π i v R R r r i I + in x + π R || R || (r + r ) r = 1 2 x π ⋅ π RI + R1 || R2 || (rx + rπ ) rx + rπ Terminal gain is vc Abc = = −gm (ro || RC || R3 ) ≅ −gm RL vb Using the Miller effect, we find CeqB = Cµ (1− Abc )+Cπ (1− Abe ) the equivalent capacitance at the base as: = Cµ (1−[−gm RL ])+Cπ (1− 0) = Cµ (1+ gm RL )+Cπ Chap 17-4 Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 4 2 Common-Emitter Amplifier – ωH High Frequency Response - Miller Effect (cont.) ! # • The total equivalent resistance ReqB = rπ 0 = rπ "rx +(RB RI )$ at the base is • The total capacitance and CeqC = Cµ +CL resistance at the collector are ReqC = ro RC R3 = RL • Because of interaction through 1 ω = Cµ, the two RC time constants p1 ! # rπ 0 "Cπ +Cµ (1+ gm RL )$+ RL (Cµ +CL ) interact, giving rise to a dominant pole. -

Notes on BJT & FET Transistors

Phys2303 L.A. Bumm [ver 1.1] Transistors (p1) Notes on BJT & FET Transistors. Comments. The name transistor comes from the phrase “transferring an electrical signal across a resistor.” In this course we will discuss two types of transistors: The Bipolar Junction Transistor (BJT) is an active device. In simple terms, it is a current controlled valve. The base current (IB) controls the collector current (IC). The Field Effect Transistor (FET) is an active device. In simple terms, it is a voltage controlled valve. The gate-source voltage (VGS) controls the drain current (ID). Regions of BJT operation: Cut-off region: The transistor is off. There is no conduction between the collector and the emitter. (IB = 0 therefore IC = 0) Active region: The transistor is on. The collector current is proportional to and controlled by the base current (IC = βIC) and relatively insensitive to VCE. In this region the transistor can be an amplifier. Saturation region: The transistor is on. The collector current varies very little with a change in the base current in the saturation region. The VCE is small, a few tenths of volt. The collector current is strongly dependent on VCE unlike in the active region. It is desirable to operate transistor switches will be in or near the saturation region when in their on state. Rules for Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJTs): • For an npn transistor, the voltage at the collector VC must be greater than the voltage at the emitter VE by at least a few tenths of a volt; otherwise, current will not flow through the collector-emitter junction, no matter what the applied voltage at the base.