High-Frequency Amplifier Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PH-218 Lec-12: Frequency Response of BJT Amplifiers

Analog & Digital Electronics Course No: PH-218 Lec-12: Frequency Response of BJT Amplifiers Course Instructors: Dr. A. P. VAJPEYI Department of Physics, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, India 1 High frequency Response of CE Amplifier At high frequencies, internal transistor junction capacitances do come into play, reducing an amplifier's gain and introducing phase shift as the signal frequency increases. In BJT, C be is the B-E junction capacitance, and C bc is the B-C junction capacitance. (output to input capacitance) At lower frequencies, the internal capacitances have a very high reactance because of their low capacitance value (usually only a few pf) and the low frequency value. Therefore, they look like opens and have no effect on the transistor's performance. As the frequency goes up, the internal capacitive reactance's go down, and at some point they begin to have a significant effect on the transistor's gain. High frequency Response of CE Amplifier When the reactance of C be becomes small enough, a significant amount of the signal voltage is lost due to a voltage-divider effect of the source resistance and the reactance of C be . When the reactance of Cbc becomes small enough, a significant amount of output signal voltage is fed back out of phase with the input (negative feedback), thus effectively reducing the voltage gain. 3 Millers Theorem The Miller effect occurs only in inverting amplifiers –it is the inverting gain that magnifies the feedback capacitance. vin − (−Av in ) iin = = vin 1( + A)× 2π × f ×CF X C Here C F represents C bc vin 1 1 Zin = = = iin 1( + A)× 2π × f ×CF 2π × f ×Cin 1( ) Cin = + A ×CF 4 High frequency Response of CE Amp.: Millers Theorem Miller's theorem is used to simplify the analysis of inverting amplifiers at high-frequencies where the internal transistor capacitances are important. -

Cascode Amplifiers by Dennis L. Feucht Two-Transistor Combinations

Cascode Amplifiers by Dennis L. Feucht Two-transistor combinations, such as the Darlington configuration, provide advantages over single-transistor amplifier stages. Another two-transistor combination in the analog designer's circuit library combines a common-emitter (CE) input configuration with a common-base (CB) output. This article presents the design equations for the basic cascode amplifier and then offers other useful variations. (FETs instead of BJTs can also be used to form cascode amplifiers.) Together, the two transistors overcome some of the performance limitations of either the CE or CB configurations. Basic Cascode Stage The basic cascode amplifier consists of an input common-emitter (CE) configuration driving an output common-base (CB), as shown above. The voltage gain is, by the transresistance method, the ratio of the resistance across which the output voltage is developed by the common input-output loop current over the resistance across which the input voltage generates that current, modified by the α current losses in the transistors: v R A = out = −α ⋅α ⋅ L v 1 2 β + + + vin RB /( 1 1) re1 RE where re1 is Q1 dynamic emitter resistance. This gain is identical for a CE amplifier except for the additional α2 loss of Q2. The advantage of the cascode is that when the output resistance, ro, of Q2 is included, the CB incremental output resistance is higher than for the CE. For a bipolar junction transistor (BJT), this may be insignificant at low frequencies. The CB isolates the collector-base capacitance, Cbc (or Cµ of the hybrid-π BJT model), from the input by returning it to a dynamic ground at VB. -

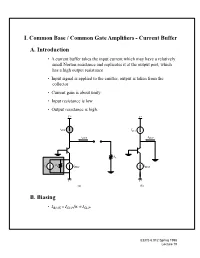

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers - Current Buffer A. Introduction • A current buffer takes the input current which may have a relatively small Norton resistance and replicates it at the output port, which has a high output resistance • Input signal is applied to the emitter, output is taken from the collector • Current gain is about unity • Input resistance is low • Output resistance is high. V+ V+ i SUP ISUP iOUT IOUT RL R is S IBIAS IBIAS V− V− (a) (b) B. Biasing = /α ≈ • IBIAS ISUP ISUP EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 II. Small Signal Two Port Parameters A. Common Base Current Gain Ai • Small-signal circuit; apply test current and measure the short circuit output current ib iout + = β v r gmv oib r − o ve roc it • Analysis -- see Chapter 8, pp. 507-509. • Result: –β ---------------o ≅ Ai = β – 1 1 + o • Intuition: iout = ic = (- ie- ib ) = -it - ib and ib is small EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 B. Common Base Input Resistance Ri • Apply test current, with load resistor RL present at the output + v r gmv r − o roc RL + vt i − t • See pages 509-510 and note that the transconductance generator dominates which yields 1 Ri = ------ gm µ • A typical transconductance is around 4 mS, with IC = 100 A • Typical input resistance is 250 Ω -- very small, as desired for a current amplifier • Ri can be designed arbitrarily small, at the price of current (power dissipation) EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 C. Common-Base Output Resistance Ro • Apply test current with source resistance of input current source in place • Note roc as is in parallel with rest of circuit g v m ro + vt it r − oc − v r RS + • Analysis is on pp. -

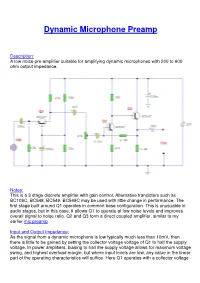

Dynamic Microphone Amplifier

Dynamic Microphone Preamp Description: A low noise pre-amplifier suitable for amplifying dynamic microphones with 200 to 600 ohm output impedance. Notes: This is a 3 stage discrete amplifier with gain control. Alternative transistors such as BC109C, BC548, BC549, BC549C may be used with little change in performance. The first stage built around Q1 operates in common base configuration. This is unusuable in audio stages, but in this case, it allows Q1 to operate at low noise levels and improves overall signal to noise ratio. Q2 and Q3 form a direct coupled amplifier, similar to my earlier mic preamp . Input and Output Impedance: As the signal from a dynamic microphone is low typically much less than 10mV, then there is little to be gained by setting the collector voltage voltage of Q1 to half the supply voltage. In power amplifiers, biasing to half the supply voltage allows for maximum voltage swing, and highest overload margin, but where input levels are low, any value in the linear part of the operating characteristics will suffice. Here Q1 operates with a collector voltage of 2.4V and a low collector current of around 200uA. This low collector current ensures low noise performance and also raises the input impedance of the stage to around 400 ohms. This is a good match for any dynamic microphone having an impedances between 200 and 600 ohms. The output impedance at Q3 is low, the graph of input and output impedance versus frequency is shown below: Gain and Frequency Response: The overall gain of this pre-amplifier is around +39dB or about 90 times. -

Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response.Pptx

EE105 – Fall 2014 Microelectronic Devices and Circuits Prof. Ming C. Wu [email protected] 511 Sutardja Dai Hall (SDH) Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 1 Common-Emitter Amplifier – ωH Open-Circuit Time Constant (OCTC) Method At high frequencies, impedances of coupling and bypass capacitors are small enough to be considered short circuits. Open-circuit time constants associated with impedances of device capacitances are considered instead. 1 ωH ≅ m ∑RioCi i=1 where Rio is resistance at terminals of ith capacitor C with all other v ! R $ i R = x = r #1+ g R + L & capacitors open-circuited. µ 0 π 0 m L ix " rπ 0 % For a C-E amplifier, assuming C = 0 L 1 1 ωH ≅ = Rπ 0 = rπ 0 Rπ 0Cπ + Rµ 0Cµ rπ 0CT Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 2 1 Common-Emitter Amplifier High Frequency Response - Miller Effect • First, find the simplified small -signal model of the C-E amp. • Replace coupling and bypass capacitors with short circuits • Insert the high frequency small -signal model for the transistor ! # rπ 0 = rπ "rx +(RB RI )$ Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 3 Common-Emitter Amplifier – ωH High Frequency Response - Miller Effect (cont.) v R r Input gain is found as A = b = in ⋅ π i v R R r r i I + in x + π R || R || (r + r ) r = 1 2 x π ⋅ π RI + R1 || R2 || (rx + rπ ) rx + rπ Terminal gain is vc Abc = = −gm (ro || RC || R3 ) ≅ −gm RL vb Using the Miller effect, we find CeqB = Cµ (1− Abc )+Cπ (1− Abe ) the equivalent capacitance at the base as: = Cµ (1−[−gm RL ])+Cπ (1− 0) = Cµ (1+ gm RL )+Cπ Chap 17-4 Lecture23-Amplifier Frequency Response 4 2 Common-Emitter Amplifier – ωH High Frequency Response - Miller Effect (cont.) ! # • The total equivalent resistance ReqB = rπ 0 = rπ "rx +(RB RI )$ at the base is • The total capacitance and CeqC = Cµ +CL resistance at the collector are ReqC = ro RC R3 = RL • Because of interaction through 1 ω = Cµ, the two RC time constants p1 ! # rπ 0 "Cπ +Cµ (1+ gm RL )$+ RL (Cµ +CL ) interact, giving rise to a dominant pole. -

Lecture 19 Common-Gate Stage

4/7/2008 Lecture 19 OUTLINE • Common‐gate stage • Source follower • Reading: Chap. 7.3‐7.4 EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 1Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley Common‐Gate Stage AvmD= gR • Common‐gate stage is similar to common‐base stage: a rise in input causes a rise in output. So the gain is positive. EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 2Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley EE105 Fall 2007 1 4/7/2008 Signal Levels in CG Stage • In order to maintain M1 in saturation, the signal swing at Vout cannot fall below Vb‐VTH EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 3Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley I/O Impedances of CG Stage 1 R = in λ =0 RRout= D gm • The input and output impedances of CG stage are similar to those of CB stage. EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 4Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley EE105 Fall 2007 2 4/7/2008 CG Stage with Source Resistance 1 g vv= m Xin1 + RS gm 1 vv g AgR==out x m vmD1 vvxin + RS gm R gR ==D mD 1 1+ gRmS + RS gm • When a source resistance is present, the voltage gain is equal to that of a CS stage with degeneration, only positive. EE105 Spring 2008 Lecture 19, Slide 5Prof. Wu, UC Berkeley Generalized CG Behavior Rgout= (1++g mrR O) S r O • When a gate resistance is present it does not affect the gain and I/O impedances since there is no potential drop across it (at low frequencies). • The output impedance of a CG stage with source resistance is identical to that of CS stage with degeneration. -

Common Gate Amplifier

© 2017 solidThinking, Inc. Proprietary and Confidential. All rights reserved. An Altair Company COMMON GATE AMPLIFIER • ACTIVATE solidThinking © 2017 solidThinking, Inc. Proprietary and Confidential. All rights reserved. An Altair Company Common Gate Amplifier A common-gate amplifier is one of three basic single-stage field-effect transistor (FET) amplifier topologies, typically used as a current buffer or voltage amplifier. In the circuit the source terminal of the transistor serves as the input, the drain is the output and the gate is connected to ground, or common, hence its name. The analogous bipolar junction transistor circuit is the common-base amplifier. Input signal is applied to the source, output is taken from the drain. current gain is about unity, input resistance is low, output resistance is high a CG stage is a current buffer. It takes a current at the input that may have a relatively small Norton equivalent resistance and replicates it at the output port, which is a good current source due to the high output resistance. • ACTIVATE solidThinking © 2017 solidThinking, Inc. Proprietary and Confidential. All rights reserved. An Altair Company Circuit Topology • ACTIVATE solidThinking © 2017 solidThinking, Inc. Proprietary and Confidential. All rights reserved. An Altair Company Waveforms Input Voltage Output Voltage • ACTIVATE solidThinking © 2017 solidThinking, Inc. Proprietary and Confidential. All rights reserved. An Altair Company The common-source and common-drain configurations have extremely high input resistances because the gate is the input terminal. In contrast, the common-gate configuration where the source is the input terminal has a low input resistance. Common gate FET configuration provides a low input impedance while offering a high output impedance. -

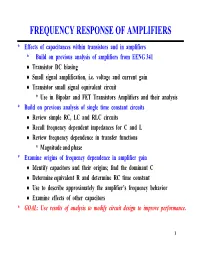

Frequency Response of Amplifiers

FREQUENCY RESPONSE OF AMPLIFIERS * Effects of capacitances within transistors and in amplifiers * Build on previous analysis of amplifiers from EENG 341 z Transistor DC biasing z Small signal amplification, i.e. voltage and current gain z Transistor small signal equivalent circuit * Use in Bipolar and FET Transistors Amplifiers and their analysis * Build on previous analysis of single time constant circuits z Review simple RC, LC and RLC circuits z Recall frequency dependent impedances for C and L z Review frequency dependence in transfer functions * Magnitude and phase * Examine origins of frequency dependence in amplifier gain z Identify capacitors and their origins; find the dominant C z Determine equivalent R and determine RC time constant z Use to describe approximately the amplifier’s frequency behavior z Examine effects of other capacitors * GOAL: Use results of analysis to modify circuit design to improve performance. 1 Analysis of Amplifier Performance * Previously analyzed z DC bias point z AC analysis (midband gain) * Neglected all capacitances in the transistor and circuit * Gain at middle frequencies, i.e. not too high or too low in frequency i B iC DC bias or quiescent point vBE vCE 2 Frequency Response of Amplifiers * In reality, all amplifiers have a limited range of frequencies of operation z Called the bandwidth of the amplifier z Falloff at low frequencies * At ~ 100 Hz to a few kHz * Due to coupling capacitors at the input or output, e.g. CC1 or CC2 z Falloff at high frequencies * At ~ 100’s MHz or few GHz 20 logT(ω) * Due to capacitances within the transistors themselves. -

Miller Effect Cascode BJT Amplifier

ESE319 Introduction to Microelectronics Miller Effect Cascode BJT Amplifier 2008 Kenneth R. Laker,update 18Oct10 KRL 1 ESE319 Introduction to Microelectronics Prototype Common Emitter Circuit Ignore “low frequency” High frequency model capacitors 2008 Kenneth R. Laker,update 18Oct10 KRL 2 ESE319 Introduction to Microelectronics Multisim Simulation Mid-band gain ∣Av∣=g m RC=40mS ∗5.1k =20446.2 dB Half-gain point 2008 Kenneth R. Laker,update 18Oct10 KRL 3 ESE319 Introduction to Microelectronics Introducing the Miller Effect The feedback connection of C between base and collector causes it to appear to the amplifier like a large capacitor 1 − K C has been inserted between the base and emitter terminals. This phenomenon is called the “Miller effect” and the capacitive multiplier “1 – K ” acting on C equals the common emitter amplifier mid-band gain, i.e. K = − g m R C . NOTE: Common base and common collector amplifiers do not suffer from the Miller effect, since in these amplifiers, one side of C is connected directly to ground. 2008 Kenneth R. Laker,update 18Oct10 KRL 4 ESE319 Introduction to Microelectronics High Frequency CC and CB Models B C E ground B v-pi C B v-pi C E E C Common Collector Common Base C is in parallel with R . C is in parallel with R . B C 2008 Kenneth R. Laker,update 18Oct10 KRL 5 ESE319 Introduction to Microelectronics Miller's Theorem I Z −I I 1=I I 2=−I + + + + V 1 K V 1 V 2 V 1 Z Z V 2=K V 1 <=> 1 2 - - - - V 1 V 1 Z V 1−V 2 V 1−K V 1 V 1 Z I = = = => 1= = = Z Z Z I 1 I 1−K 1−K 1 Z 1= 1 j 2 f C 1−K V 2− V 2 V 2−V 2 K V 2 −I = = = V 2 V 2 Z Z Z Z Z = = = ≈ Z => 2 I −I 1 if K >> 1 1 2 1− 1− K K approx. -

The Common Base Amplifier

The common base amplifier The final transistor amplifier configuration (Figure below) we need to study is the common-base. This configuration is more complex than the other two, and is less common due to its strange operating characteristics. Common-base amplifier It is called the common-base configuration because (DC power source aside), the signal source and the load share the base of the transistor as a common connection point shown in Figure below. Common-base amplifier: Input between emitter and base, output between collector and base. Perhaps the most striking characteristic of this configuration is that the input signal source must carry the full emitter current of the transistor, as indicated by the heavy arrows in the first illustration. As we know, the emitter current is greater than any other current in the transistor, being the sum of base and collector currents. In the last two amplifier configurations, the signal source was connected to the base lead of the transistor, thus handling the leastcurrent possible. Because the input current exceeds all other currents in the circuit, including the output current, the current gain of this amplifier is actually less than 1(notice how Rload is connected to the collector, thus carrying slightly less current than the signal source). In other words, it attenuates current rather thanamplifying it. With common-emitter and common-collector amplifier configurations, the transistor parameter most closely associated with gain was β. In the common-base circuit, we follow another basic transistor parameter: the ratio between collector current and emitter current, which is a fraction always less than 1. -

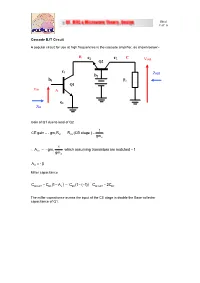

Cascode BJT Circuit

Sheet 1 of 6 Cascode BJT Circuit A popular circuit for use at high frequencies is the cascode amplifier, as shown below:- B e2 c2 C Vout Q2 c1 Zout b2 b1 RL Q1 Vin A e1 Zin Gain of Q1 due to load of Q2 1 CE gain = - gm1RL1 RIN (CB stage ) = gm2 1 ∴ A V 1 = - gm1 which assuming transistors are matched = 1 gm2 AI1 = - β Miller capacitance CSHUNT = CBC ()1− Av = CBC (1− (−1)) CSHUNT = 2CBC The miller capacitance across the input of the CE stage is double the Base collector capacitance of Q1. Sheet 2 of 6 Input Impedance of Q1 at point A is β ICQ k.T -23 −1 RIN = where gm = ; VT = where k = Boltzmans constant = 1.3807x10 JK gm VT q q = Electron charge = 1.6022x10-19C T = Temperature in Kelvin gm = Transconductance (mS) Voltage Gain Av Voltage gain of CE stage is ~ 1 (due to low output RL) so the voltage gain of the amplifier will be from the common-base stage: VOUT β2.ib2.RL β2.RL RL ICQ VA VA 1 A V = = = ≈ = . = (as = rce ) VIN ib2 (β2 + 1)rbe2 (β2 + 1)rbe2 rbe VT ICQ VT gm Current Gain Ai Current gain of CB stage is ~ 1 so the current gain of the amplifier will be from the common- emitter stage. Current gain (Ai) = Ai of the CE stage (Ai of CB stage = 1) = β Output Impedance ROUT = RL Of course as the voltage gain of the whole amplifier is dependant on the load resistor (and ultimately rce2), then adding an active load (eg current mirror) will allow high voltage gain. -

Chapter 8 NOISE, GAIN and BANDWIDTH in ANALOG DESIGN

Chapter 8 NOISE, GAIN AND BANDWIDTH IN ANALOG DESIGN Robert G. Meyer Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California Trade-offs between noise, gain and bandwidth are important issues in analog circuit design. Noise performance is a primary concern when low-level sig- nals must be amplified. Optimization of noise performance is a complex task involving many parameters. The circuit designer must decide the basic form of amplification required – whether current input, voltage input or an impedance- matched input. Various parameters which can then be manipulated to optimize the noise performance include device sizes and bias currents, device types (FET or bipolar), circuit topologies (Darlington, cascode, etc.) and circuit impedance levels. The complexity of this situation is then further compounded when the issue of gain–bandwidth is included. A fundamental distinction to be made here is between noise issues in wideband amplifier design versus narrowband amplifier design. Wideband amplifiers generally have bandwidths of several octaves or more and may have to operate down to dc. This generally means that inductive elements cannot be used to enhance performance. By contrast, narrowband amplifiers may have bandwidths of as little as 10% or less of their center frequency, and inductors can be used to great advantage in trading gain for bandwidth and also in improving the circuit noise performance. In order to explore these issues and trade-offs, we begin first with a description of gain– bandwidth concepts as applied to both wideband and narrowband amplifiers, followed by a treatment of electronic circuit noise modeling. These concepts are then used in combination to define the trade-offs in circuit design between noise, gain and bandwidth.