Game: Marine Food Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backyard Food

Suggested Grades: 2nd - 5th BACKYARD FOOD WEB Wildlife Champions at Home Science Experiment 2-LS4-1: Make observations of plants and animals to compare the diversity of life in different habitats. What is a food web? All living things on earth are either producers, consumers or decomposers. Producers are organisms that create their own food through the process of photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is when a living thing uses sunlight, water and nutrients from the soil to create its food. Most plants are producers. Consumers get their energy by eating other living things. Consumers can be either herbivores (eat only plants – like deer), carnivores (eat only meat – like wolves) or omnivores (eat both plants and meat - like humans!) Decomposers are organisms that get their energy by eating dead plants or animals. After a living thing dies, decomposers will break down the body and turn it into nutritious soil for plants to use. Mushrooms, worms and bacteria are all examples of decomposers. A food web is a picture that shows how energy (food) passes through an ecosystem. The easiest way to build a food web is by starting with the producers. Every ecosystem has plants that make their own food through photosynthesis. These plants are eaten by herbivorous consumers. These herbivores are then hunted by carnivorous consumers. Eventually, these carnivores die of illness or old age and become food for decomposers. As decomposers break down the carnivore’s body, they create delicious nutrients in the soil which plants will use to live and grow! When drawing a food web, it is important to show the flow of energy (food) using arrows. -

Biogeography, Community Structure and Biological Habitat Types of Subtidal Reefs on the South Island West Coast, New Zealand

Biogeography, community structure and biological habitat types of subtidal reefs on the South Island West Coast, New Zealand SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 281 Biogeography, community structure and biological habitat types of subtidal reefs on the South Island West Coast, New Zealand Nick T. Shears SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 281 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand Cover: Shallow mixed turfing algal assemblage near Moeraki River, South Westland (2 m depth). Dominant species include Plocamium spp. (yellow-red), Echinothamnium sp. (dark brown), Lophurella hookeriana (green), and Glossophora kunthii (top right). Photo: N.T. Shears Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright December 2007, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 (hardcopy) ISSN 1177–9241 (web PDF) ISBN 978–0–478–14354–6 (hardcopy) ISBN 978–0–478–14355–3 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. -

Community Ecology

Schueller 509: Lecture 12 Community ecology 1. The birds of Guam – e.g. of community interactions 2. What is a community? 3. What can we measure about whole communities? An ecology mystery story If birds on Guam are declining due to… • hunting, then bird populations will be larger on military land where hunting is strictly prohibited. • habitat loss, then the amount of land cleared should be negatively correlated with bird numbers. • competition with introduced black drongo birds, then….prediction? • ……. come up with a different hypothesis and matching prediction! $3 million/yr Why not profitable hunting instead? (Worked for the passenger pigeon: “It was the demographic nightmare of overkill and impaired reproduction. If you’re killing a species far faster than they can reproduce, the end is a mathematical certainty.” http://www.audubon.org/magazine/may-june- 2014/why-passenger-pigeon-went-extinct) Community-wide effects of loss of birds Schueller 509: Lecture 12 Community ecology 1. The birds of Guam – e.g. of community interactions 2. What is a community? 3. What can we measure about whole communities? What is an ecological community? Community Ecology • Collection of populations of different species that occupy a given area. What is a community? e.g. Microbial community of one human “YOUR SKIN HARBORS whole swarming civilizations. Your lips are a zoo teeming with well- fed creatures. In your mouth lives a microbiome so dense —that if you decided to name one organism every second (You’re Barbara, You’re Bob, You’re Brenda), you’d likely need fifty lifetimes to name them all. -

Seventh Grade

Name: _____________________ Maui Ocean Center Learning Worksheet Seventh Grade Our mission is to foster understanding, wonder and respect for Hawai‘i’s Marine Life. Based on benchmarks SC.6.3.1, SC. 7.3.1, SC. 7.3.2, SC. 7.5.4 Maui Ocean Center SEVENTH GRADE 1 Interdependent Relationships Relationships A food web (or chain) shows how each living thing gets its food. Some animals eat plants and some animals eat other animals. For example, a simple food chain links plants, cows (that eat plants), and humans (that eat cows). Each link in this chain is food for the next link. A food chain always starts with plant life and ends with an animal. Plants are called producers (they are also autotrophs) because they are able to use light energy from the sun to produce food (sugar) from carbon dioxide and water. Animals cannot make their own food so they must eat plants and/or other animals. They are called consumers (they are also heterotrophs). There are three groups of consumers. Animals that eat only plants are called herbivores. Animals that eat other animals are called carnivores. Animals and people who eat both animals and plants are called omnivores. Decomposers (bacteria and fungi) feed on decaying matter. These decomposers speed up the decaying process that releases minerals back into the food chain for absorption by plants as nutrients. Do you know why there are more herbivores than carnivores? In a food chain, energy is passed from one link to another. When a herbivore eats, only a fraction of the energy (that it gets from the plant food) becomes new body mass; the rest of the energy is lost as waste or used up (by the herbivore as it moves). -

Islands in the Stream 2002: Exploring Underwater Oases

Islands in the Stream 2002: Exploring Underwater Oases NOAA: Office of Ocean Exploration Mission Three: SUMMARY Discovery of New Resources with Pharmaceutical Potential (Pharmaceutical Discovery) Exploration of Vision and Bioluminescence in Deep-sea Benthos (Vision and Bioluminescence) Microscopic view of a Pachastrellidae sponge (front) and an example of benthic bioluminescence (back). August 16 - August 31, 2002 Shirley Pomponi, Co-Chief Scientist Tammy Frank, Co-Chief Scientist John Reed, Co-Chief Scientist Edie Widder, Co-Chief Scientist Pharmaceutical Discovery Vision and Bioluminescence Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution ABSTRACT Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution (HBOI) scientists continued their cutting-edge exploration searching for untapped sources of new drugs, examining the visual physiology of deep-sea benthos and characterizing the habitat in the South Atlantic Bight aboard the R/V Seaward Johnson from August 16-31, 2002. Over a half-dozen new species of sponges were recorded, which may provide scientists with information leading to the development of compounds used to study, treat, or diagnose human diseases. In addition, wondrous examples of bioluminescence and emission spectra were recorded, providing scientists with more data to help them understand how benthic organisms visualize their environment. New and creative Table of Contents ways to outreach and educate the public also Key Findings and Outcomes................................2 Rationale and Objectives ....................................4 -

Plants Are Producers! Draw the Different Producers Below

Name: ______________________________ The Unique Producer Every food chain begins with a producer. Plants are producers. They make their own food, which creates energy for them to grow, reproduce and survive. Being able to make their own food makes them unique; they are the only living things on Earth that can make their own source of food energy. Of course, they require sun, water and air to thrive. Given these three essential ingredients, you will have a healthy plant to begin the food chain. All plants are producers! Draw the different producers below. Apple Tree Rose Bushes Watermelon Grasses Plant Blueberry Flower Fern Daisy Bush List the three essential needs that every producer must have in order to live. © 2009 by Heather Motley Name: ______________________________ Producers can make their own food and energy, but consumers are different. Living things that have to hunt, gather and eat their food are called consumers. Consumers have to eat to gain energy or they will die. There are four types of consumers: omnivores, carnivores, herbivores and decomposers. Herbivores are living things that only eat plants to get the food and energy they need. Animals like whales, elephants, cows, pigs, rabbits, and horses are herbivores. Carnivores are living things that only eat meat. Animals like owls, tigers, sharks and cougars are carnivores. You would not catch a plant in these animals’ mouths. Then, we have the omnivores. Omnivores will eat both plants and animals to get energy. Whichever food source is abundant or available is what they will eat. Animals like the brown bear, dogs, turtles, raccoons and even some people are omnivores. -

Interactions Between Organisms . and Environment

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN ORGANISMS . AND ENVIRONMENT 2·1 FUNCTIONAL RELATIONSHIPS An understanding of the relationships between an organism and its environment can be attained only when the environmental factors that can be experienced by the organism are considered. This is difficult because it is first necessary for the ecologist to have some knowledge of the neurological and physiological detection abilities of the organism. Sound, for example, should be measured with an instrument that responds to sound energy in the same way that the organism being studied does. Snow depths should be measured in a manner that reflects their effect on the animal. If six inches of snow has no more effect on an animal than three inches, a distinction between the two depths is meaningless. Six inches is not twice three inches in terms of its effect on the animal! Lower animals differ from man in their response to environmental stimuli. Color vision, for example, is characteristic of man, monkeys, apes, most birds, some domesticated animals, squirrels, and, undoubtedly, others. Deer and other wild ungulates probably detect only shades of grey. Until definite data are ob tained on the nature of color vision in an animal, any measurement based on color distinctions could be misleading. Infrared energy given off by any object warmer than absolute zero (-273°C) is detected by thermal receptors on some animals. Ticks are sensitive to infrared radiation, and pit vipers detect warm prey with thermal receptors located on the anterior dorsal portion of the skull. Man can detect different levels of infrared radiation with receptors on the skin, but they are not directional nor are they as sensitive as those of ticks and vipers. -

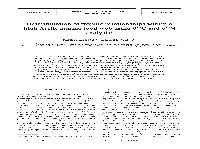

Determination of Trophic Relationships Within a High Arctic Marine Food Web Using 613C and 615~ Analysis *

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published July 23 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Determination of trophic relationships within a high Arctic marine food web using 613c and 615~ analysis * Keith A. ~obson'.2, Harold E. welch2 ' Department of Biology. University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Canada S7N OWO Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Freshwater Institute, 501 University Crescent, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N6 ABSTRACT: We measured stable-carbon (13C/12~)and/or nitrogen (l5N/l4N)isotope ratios in 322 tissue samples (minus lipids) representing 43 species from primary producers through polar bears Ursus maritimus in the Barrow Strait-Lancaster Sound marine food web during July-August, 1988 to 1990. 613C ranged from -21.6 f 0.3%0for particulate organic matter (POM) to -15.0 f 0.7%0for the predatory amphipod Stegocephalus inflatus. 615~was least enriched for POM (5.4 +. O.8%0), most enriched for polar bears (21.1 f 0.6%0), and showed a step-wise enrichment with trophic level of +3.8%0.We used this enrichment value to construct a simple isotopic food-web model to establish trophic relationships within thls marine ecosystem. This model confirms a food web consisting primanly of 5 trophic levels. b13C showed no discernible pattern of enrichment after the first 2 trophic levels, an effect that could not be attributed to differential lipid concentrations in food-web components. Although Arctic cod Boreogadus saida is an important link between primary producers and higher trophic-level vertebrates during late summer, our isotopic model generally predicts closer links between lower trophic-level invertebrates and several species of seabirds and marine mammals than previously established. -

Controls and Structure of the Microbial Loop

Controls and Structure of the Microbial Loop A symposium organized by the Microbial Oceanography summer course sponsored by the Agouron Foundation Saturday, July 1, 2006 Asia Room, East-West Center, University of Hawaii Symposium Speakers: Peter J. leB Williams (University of Bangor, Wales) David L. Kirchman (University of Delaware) Daniel J. Repeta (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute) Grieg Steward (University of Hawaii) The oceans constitute the largest ecosystems on the planet, comprising more than 70% of the surface area and nearly 99% of the livable space on Earth. Life in the oceans is dominated by microbes; these small, singled-celled organisms constitute the base of the marine food web and catalyze the transformation of energy and matter in the sea. The microbial loop describes the dynamics of microbial food webs, with bacteria consuming non-living organic matter and converting this energy and matter into living biomass. Consumption of bacteria by predation recycles organic matter back into the marine food web. The speakers of this symposium will explore the processes that control the structure and functioning of microbial food webs and address some of these fundamental questions: What aspects of microbial activity do we need to measure to constrain energy and material flow into and out of the microbial loop? Are we able to measure bacterioplankton dynamics (biomass, growth, production, respiration) well enough to edu/agouroninstitutecourse understand the contribution of the microbial loop to marine systems? What factors control the flow of material and energy into and out of the microbial loop? At what scales (space and time) do we need to measure processes controlling the growth and metabolism of microorganisms? How does our knowledge of microbial community structure and diversity influence our understanding of the function of the microbial loop? Program: 9:00 am Welcome and Introductory Remarks followed by: Peter J. -

Evidence for Ecosystem-Level Trophic Cascade Effects Involving Gulf Menhaden (Brevoortia Patronus) Triggered by the Deepwater Horizon Blowout

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Evidence for Ecosystem-Level Trophic Cascade Effects Involving Gulf Menhaden (Brevoortia patronus) Triggered by the Deepwater Horizon Blowout Jeffrey W. Short 1,*, Christine M. Voss 2, Maria L. Vozzo 2,3 , Vincent Guillory 4, Harold J. Geiger 5, James C. Haney 6 and Charles H. Peterson 2 1 JWS Consulting LLC, 19315 Glacier Highway, Juneau, AK 99801, USA 2 Institute of Marine Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 3431 Arendell Street, Morehead City, NC 28557, USA; [email protected] (C.M.V.); [email protected] (M.L.V.); [email protected] (C.H.P.) 3 Sydney Institute of Marine Science, Mosman, NSW 2088, Australia 4 Independent Researcher, 296 Levillage Drive, Larose, LA 70373, USA; [email protected] 5 St. Hubert Research Group, 222 Seward, Suite 205, Juneau, AK 99801, USA; [email protected] 6 Terra Mar Applied Sciences LLC, 123 W. Nye Lane, Suite 129, Carson City, NV 89706, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-907-209-3321 Abstract: Unprecedented recruitment of Gulf menhaden (Brevoortia patronus) followed the 2010 Deepwater Horizon blowout (DWH). The foregone consumption of Gulf menhaden, after their many predator species were killed by oiling, increased competition among menhaden for food, resulting in poor physiological conditions and low lipid content during 2011 and 2012. Menhaden sampled Citation: Short, J.W.; Voss, C.M.; for length and weight measurements, beginning in 2011, exhibited the poorest condition around Vozzo, M.L.; Guillory, V.; Geiger, H.J.; Barataria Bay, west of the Mississippi River, where recruitment of the 2010 year class was highest. -

Herbivore Physiological Response to Predation Risk and Implications for Ecosystem Nutrient Dynamics

Herbivore physiological response to predation risk and implications for ecosystem nutrient dynamics Dror Hawlena and Oswald J. Schmitz1 School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511 Communicated by Thomas W. Schoener, University of California, Davis, CA, June 29, 2010 (received for review January 4, 2010) The process of nutrient transfer throughan ecosystem is an important lower the quantity of energy that can be allocated to production determinant of production, food-chain length, and species diversity. (20–23). Consequently, stress-induced constraints on herbivore The general view is that the rate and efficiency of nutrient transfer up production should lower the demand for N-rich proteins (24). the food chain is constrained by herbivore-specific capacity to secure Herbivores also have low capacity to store excess nutrients (24), N-rich compounds for survival and production. Using feeding trials and hence should seek plants with high digestible carbohydrate with artificial food, we show, however, that physiological stress- content to minimize the costs of ingesting and excreting excess N. response of grasshopper herbivores to spider predation risk alters the Such stress-induced shift in nutrient demand may be especially nature of the nutrient constraint. Grasshoppers facing predation risk important in terrestrial systems in which digestible carbohydrate had higher metabolic rates than control grasshoppers. Elevated represents a small fraction of total plant carbohydrate-C, and may metabolism accordingly increased requirements for dietary digestible be limiting even under risk-free conditions (25). Moreover, stress carbohydrate-C to fuel-heightened energy demands. Moreover, di- responses include break down of body proteins to produce glucose gestible carbohydrate-C comprises a small fraction of total plant (i.e., gluconeogenesis) (14), which requires excretion of N-rich tissue-C content, so nutrient transfer between plants and herbivores waste compounds (ammonia or primary amines) (26). -

Habitat Evaluation: Guidance for the Review of Environmental Impact Assessment Documents

HABITAT EVALUATION: GUIDANCE FOR THE REVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT DOCUMENTS EPA Contract No. 68-C0-0070 work Assignments B-21, 1-12 January 1993 Submitted to: Jim Serfis U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Federal Activities 401 M Street, SW Washington, DC 20460 Submitted by: Mark Southerland Dynamac Corporation The Dynamac Building 2275 Research Boulevard Rockville, MD 20850 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ... ...... .... ... ................................................. 1 Habitat Conservation .......................................... 2 Habitat Evaluation Methodology ................................... 2 Habitats of Concern ........................................... 3 Definition of Habitat ..................................... 4 General Habitat Types .................................... 5 Values and Services of Habitats ................................... 5 Species Values ......................................... 5 Biological diversity ...................................... 6 Ecosystem Services.. .................................... 7 Activities Impacting Habitats ..................................... 8 Land Conversion ....................................... 9 Land Conversion to Industrial and Residential Uses ............. 9 Land Conversion to Agricultural Uses ...................... 10 Land Conversion to Transportation Uses .................... 10 Timber Harvesting ...................................... 11 Grazing ............................................. 12 Mining .............................................