U.S. Military Bases and Force Realignments in Japan and Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management

e Fukushima Nuclearand Crisis Accident Management e Fukushima The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. September, 2012 e Sasakawa Peace Foundation Foreword This report is the culmination of a research project titled ”Assessment: Japan-US Response to the Fukushima Crisis,” which the Sasakawa Peace Foundation launched in July 2011. The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that resulted from the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, involved the dispersion and spread of radioactive materials, and thus from both the political and economic perspectives, the accident became not only an issue for Japan itself but also an issue requiring international crisis management. Because nuclear plants can become the target of nuclear terrorism, problems related to such facilities are directly connected to security issues. However, the policymaking of the Japanese government and Japan-US coordination in response to the Fukushima crisis was not implemented smoothly. This research project was premised upon the belief that it is extremely important for the future of the Japan-US relationship to draw lessons from the recent crisis and use that to deepen bilateral cooperation. The objective of this project was thus to review and analyze the lessons that can be drawn from US and Japanese responses to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and on the basis of these assessments, to contribute to enhancing the Japan-US alliance’s nuclear crisis management capabilities, including its ability to respond to nuclear terrorism. -

The Politics of the Futenma Base Issue in Okinawa: Relocation Negotiations in 1995-1997, 2005-2006

Asia-Pacific Policy Papers Series THE POLITICS OF THE FUTENMA BASE ISSUE IN OKINAWA: RELOCATION NEGOTIATIONS IN 1995-1997, 2005-2006 By William L. Brooks Johns Hopkins University The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies tel. 202-663-5812 email: [email protected] The Edwin O. Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies Established in 1984, with the explicit support of the Reischauer family, the Edwin O. Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) actively supports the research and study of trans-Pacific and intra-Asian relations to advance mutual understanding between North-east Asia and the United States. The first Japanese-born and Japanese-speaking US Ambassador to Japan, Edwin O. Reischauer (serv. 1961–66) later served as the center’s Honorary Chair from its founding until 1990. His wife Haru Matsukata Reischauer followed as Honorary Chair from 1991 to 1998. They both exemplified the deep commitment that the Reischauer Center aspires to perpetuate in its scholarly and cultural activities today. Asia-Pacific Policy Papers Series THE POLITICS OF THE FUTENMA BASE ISSUE IN OKINAWA: RELOCATION NEGOTIATIONS IN 1995-1997, 2005-2006 By William L. Brooks William L. Brooks William L. Brooks, an adjunct professor for Japan Studies, has 15 years of experience as head at the Embassy Tokyo’s Office of Media Analysis and Translation unit spanning from 1993 until his retirement in September 2009. Dr. Brooks also served as a senior researcher at the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research and provided the Secretary of State and Washington with policy analysis on Japan (1983-1987, 1990-1993). -

India-Japan Maritime Security Cooperation (1999-2009) : a Report PANNEERSELVAM, Prakash Guest Researcher “A Strong India Is I

JMSDF Staff College Review Volume 2 English version (Selected) India-Japan Maritime Security Cooperation (1999-2009) : A Report PANNEERSELVAM, Prakash Guest Researcher “A Strong India is in the best interest of Japan, and a strong Japan is in the best interest of India.” Former Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe Speech at the Indian parliament, 22 August 2007 Introduction India-Japan interactions have been marked by goodwill and singularly free from any structural impediments. However, the bilateral relationship between the two started to take centre stage only after the end of Cold War. However, both countries refrained from discussing defence and security matters, until Prime Minister Mori visit to India in 2000. The brief talk between two Prime Ministers in New Delhi removed many deadlocks in the bilateral relationship. Since then, India-Japan relationship maintained steady course and attained the stature of “Strategic Partnership” in 2005. The remarkable change in Indo-Japan relationship in the post-Cold War dramatically changed the security perspective of Asia-pacific region. Notably, maritime security cooperation between the two countries captured global attention. At the same time, the growing interaction between two naval forces in the recent years raised some serious questions about the intention and objectives of India-Japan maritime security cooperation. A preliminary literature survey on this topic reveals that, not too many research works has been done on this subject. Most of literature on India-Japan relationship largely focuses on complicated relationship that existed between two countries during post-world war era or bilateral relationship in Post-Cold War. This policy analysis is important because it focuses exclusively on India-Japan maritime security cooperation to identify the key factor to strengthen the strategic cooperation. -

Roster of Winners in Single-Seat Constituencies No

Tuesday, October 24, 2017 | The Japan Times | 3 lower house ele ion ⑳ NAGANO ㉘ OSAKA 38KOCHI No. 1 Takashi Shinohara (I) No. 1 Hiroyuki Onishi (L) No. 1 Gen Nakatani (L) Roster of winners in single-seat constituencies No. 2 Mitsu Shimojo (KI) No. 2 Akira Sato (L) No. 2 Hajime Hirota (I) No. 3 Yosei Ide (KI) No. 3 Shigeki Sato (K) No. 4 Shigeyuki Goto (L) No. 4 Yasuhide Nakayama (L) 39EHIME No. 4 Masaaki Taira (L) ⑮ NIIGATA No. 5 Ichiro Miyashita (L) No. 5 Toru Kunishige (K) No. 1 Yasuhisa Shiozaki (L) ( L ) Liberal Democratic Party; ( KI ) Kibo no To; ( K ) Komeito; No. 5 Kenji Wakamiya (L) No. 6 Shinichi Isa (K) No. 1 Chinami Nishimura (CD) No. 2 Seiichiro Murakami (L) ( JC ) Japanese Communist Party; ( CD ) Constitutional Democratic Party; No. 6 Takayuki Ochiai (CD) No. 7 Naomi Tokashiki (L) No. 2 Eiichiro Washio (I) ㉑ GIFU No. 3 Yoichi Shiraishi (KI) ( NI ) Nippon Ishin no Kai; ( SD ) Social Democratic Party; ( I ) Independent No. 7 Akira Nagatsuma (CD) No. 8 Takashi Otsuka (L) No. 3 Takahiro Kuroiwa (I) No. 1 Seiko Noda (L) No. 4 Koichi Yamamoto (L) No. 8 Nobuteru Ishihara (L) No. 9 Kenji Harada (L) No. 4 Makiko Kikuta (I) No. 2 Yasufumi Tanahashi (L) No. 9 Isshu Sugawara (L) No. 10 Kiyomi Tsujimoto (CD) No. 4 Hiroshi Kajiyama (L) No. 3 Yoji Muto (L) 40FUKUOKA ① HOKKAIDO No. 10 Hayato Suzuki (L) No. 11 Hirofumi Hirano (I) No. 5 Akimasa Ishikawa (L) No. 4 Shunpei Kaneko (L) No. 1 Daiki Michishita (CD) No. 11 Hakubun Shimomura (L) No. -

Japan's New Defense Establishment

JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT: INSTITUTIONS, CAPABILITIES, AND IMPLICATIONS Yuki Tatsumi and Andrew L. Oros Editors March 2007 ii | JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT Copyright ©2007 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-5-7 Photos by US Government and Ministry of Defense in Japan. Cover design by Rock Creek Creative. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org YUKI TATSUMI AND ANDREW L. OROS | iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................... v Preface ............................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements...........................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: JAPAN’S EVOLVING DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT .......................... 9 CHAPTER 2: SELF DEFENSE FORCES TODAY— BEYOND AN EXCLUSIVELY DEFENSE –ORIENTED POSTURE? ........................... 23 CHAPTER 3: THE LEGAL AND POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE SELF-DEFENSE FORCES’ OVERSEAS DEPLOYMENTS ......................................... 47 CHAPTER 4: THE UNITED STATES AND “ALLIANCE” ROLE IN JAPAN’S -

Pacific Partners: Forging the US-Japan Special Relationship

Pacific Partners: Forging the U.S.-Japan Special Relationship 太平洋のパートナー:アメリカと日本の特別な関係の構築 Arthur Herman December 2017 Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Research Report Pacific Partners: Forging the U.S.-Japan Special Relationship 太平洋のパートナー:アメリカと日本の特別な関係の構築 Arthur Herman Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute © 2017 Hudson Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. For more information about obtaining additional copies of this or other Hudson Institute publications, please visit Hudson’s website, www.hudson.org Hudson is grateful for the support of the Smith Richardson Foundation in funding the research and completion of this report. ABOUT HUDSON INSTITUTE Hudson Institute is a research organization promoting American leadership and global engagement for a secure, free, and prosperous future. Founded in 1961 by strategist Herman Kahn, Hudson Institute challenges conventional thinking and helps manage strategic transitions to the future through interdisciplinary studies in defense, international relations, economics, health care, technology, culture, and law. Hudson seeks to guide public policy makers and global leaders in government and business through a vigorous program of publications, conferences, policy briefings and recommendations. Visit www.hudson.org for more information. Hudson Institute 1201 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20004 P: 202.974.2400 [email protected] www.hudson.org Table of Contents Introduction (イントロダクション) 3 Part I: “Allies of a Kind”: The US-UK Special Relationship in 15 Retrospect(パート I:「同盟の一形態」:米英の特別な関係は過去どうだったの -

Strategic Yet Strained

INTRODUCTION | i STRATEGIC YET STRAINED US FORCE REALIGNMENT IN JAPAN AND ITS EFFECTS ON OKINAWA Yuki Tatsumi, Editor September 2008 ii | STRATEGIC YET STRAINED Copyright ©2008 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-8-1 Photos from the US Government Cover design by Rock Creek Creative All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms............................................................................................................. v Preface ..............................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements............................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Yuki Tatsumi and Arthur Lord SECTION I: THE CONTEXT CHAPTER 1: THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW OF THE UNITED STATES: “REDUCE, MAINTAIN, AND ENHANCE”............................................................... 13 Derek J. Mitchell CHAPTER 2: THE US STRATEGY BEYOND THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW ...... 25 Tsuneo “Nabe” Watanabe CHAPTER 3: THE LEGACY OF PRIME MINISTER KOIZUMI’S JAPANESE FOREIGN POLICY: AN ASSESSMENT ................................................................... -

460 Reference

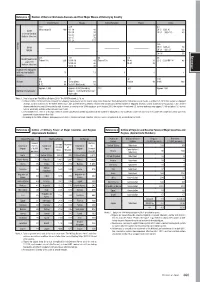

Reference 1 Number of Nuclear Warheads Arsenals and Their Major Means of Delivery by Country United States Russia United Kingdom France China 400 334 60 Minuteman III 400 SS-18 46 DF-5 CSS-4 20 ICBM ( ) SS-19 30 DF-31(CSS-10) 40 (Intercontinental ― ― SS-25 63 Ballistic Missiles) SS-27 78 RS-24 117 Missiles 148 IRBM DF-4(CSS-3) 10 ― ― ― ― MRBM DF-21(CSS-5) 122 DF-26 30 Reference 336 192 48 64 48 SLBM (Submarine Trident D-5 336 SS-N-18 48 Trident D-5 48 M-45 16 JL-2 CSS-NX-14 48 Launched ( ) SS-N-23 96 M-51 48 Ballistic Missiles) SS-N-32 48 Submarines equipped with nuclear ballistic 14 13 4 4 4 missiles 66 76 40 100 Aircraft B-2 20 Tu-95 (Bear) 60 ― Rafale 40 H-6K 100 B-52 46 Tu-160 (Blackjack) 16 Approx. 3,800 Approx. 4,350 (including 215 300 Approx. 280 Number of warheads Approx. 1,830 tactical nuclear warheads) Notes: 1. Data is based on “The Military Balance 2019,” the SIPRI Yearbook 2018, etc. 2. In March 2019, the United States released the following figures based on the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia as of March 1, 2019: the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the United States was 1,365 and the delivery vehicles involved 656 missiles/aircraft; the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for Russia was 1,461 and the delivery vehicles involved 524 missiles/aircraft. However, according to the SIPRI database, as of January 2018, the number of deployed U.S. -

Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—The National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2009 Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—the National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010 Tadashi Watanabe University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Watanabe, Tadashi, "Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—the National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 690. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/690 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Japan’s Preventive Strategy: Secure the World – The National Defense Program Guidelines in and after FY 2010 – A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in International Security by Tadashi Watanabe June 2009 Advisors: Paul R. Viotti, Ph.D. Anthony Hayter, Ph.D. Col. Thomas A. Drohan, Ph.D. i ©Copyright by Tadashi Watanabe 2009 All Right Reserved ii Author: Tadashi Watanabe Title: Japan’s Preventive Strategy: Secure the World – The National Defense Program Guidelines in and after FY 2010 – Advisors: Paul R. Viotti, Ph.D. Anthony Hayter, Ph.D. Col. Thomas A. -

U.S.-Japan Alliance Conference: Meeting the Challenge Of

NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE U.S.-Japan Alliance Conference Meeting the Challenge of Amphibious Operations Scott W. Harold, Koichiro Bansho, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Koichi Isobe, Richard L. Simcock II Sponsored by the Government of Japan For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF387 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface In order to explore the origins, development, and implications of Japan’s decision to establish an Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade (ARDB) within the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF), the RAND Corporation convened a public conference on March 6, 2018, at its offices in Santa Monica, California, that brought together leading U.S. -

Reference 1. Major Nuclear Forces

Reference Reference 1. Major Nuclear Forces U.S. Russia U.K. France China 550 508 46 Intercontinental Minuteman III: 500 SS-18: 80 DF-5 (CSS-4): 20 ballistic missiles Peacekeeper: 50 SS-19: 126 — — DF-31 (CSS-9): 6 (ICBMs) SS-25: 254 DF-4 (CSS-3): 20 SS-27: 48 35 IRBMs — — — — DF-3 (CSS-2): 2 MRBMs DF-21 (CSS-5): 33 SRBMs — — — — 725 Missiles 432 252 48 64 12 Trident C-4: 120 SS-N-18: 96 Trident D-5: 48 M-45: 64 JL-1 (CSS-N-3): 12 Submarine Trident D-5: 312 SS-N-19: 60 (SSBN [Nuclear- (SSBN [Nuclear- (SSBN [Nuclear- launched (SSBN [Nuclear- SS-N-23: 96 powered submarines powered submarines powered submarines ballistic missiles powered submarines (SSBN [Nuclear- with ballistic missile with ballistic missile with ballistic missile (SLBMs) with ballistic missile powered submarines payloads]: 4) payloads]: 4) payloads]: 1) payloads]: 14) with ballistic missile payloads]: 15) 114 79 Long-distance B-2: 19 Tu-95 (Bear): 64 — — — (strategic) bombers B-52: 94 Tu-160 (Blackjack): 15 Note: Sources: Military Balance 2008, etc. — 391 — Reference 2. Performance of Major Ballistic and Cruise Missiles Maximum Item Country Name Warhead (yield) Guidance System Remarks range MIRV (170 KT, 335-350 KT or Minuteman III 13,000 Inertial Three-stage solid U.S. 300-475 KT × 3) Peacekeeper 9,600 MIRV (300–475 KT × 10) Inertial Three-stage solid MIRV (1.3 MT × 8, 500 -550 KT × 10 or SS-18 10,500-16,000 Inertial Two-stage liquid 500-750KT × 10) or Single (24MT) Russia MIRV (550 KT × 6 or 500-750 ICBM SS-19 9,000-10,000 Inertial Two-stage liquid KT × 6) SS-25 10,500 Single (550 KT) Inertial + Computer control Three-stage solid SS-27 10,500 Single (550 KT) Inertial + GLONASS Three-stage solid Single (4 MT) or DF-5 (CSS-4) 12,000-13,000 Inertial Two-stage liquid MIRV (150-350 KT × 4-6) China Single (1 MT) or DF-31 (CSS-9) 8,000-14,000 Inertial + Stellar reference Three-stage solid MIRV (20–150 KT × 3–5) Trident C-4 7,400 MIRV (100 KT × 8) Inertial + Stellar reference Three-stage solid U.S. -

Chapter 8 CBRN Defense: Responding to Growing Threats

Chapter 8 CBRN Defense: Responding to Growing Threats n the wake of the Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attacks in Japan in 1994 and 1995, Iand the 9/11 and anthrax mail attacks in the United States in 2001, threats involving the use of chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear materials/ agents have come to be collectively referred to as CBRN threats. This term broadly encompasses not only the traditional concept of NBC attacks—those by nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons—but also terrorist attacks, accidents, or natural disasters. Given these intricacies, this chapter proposes using the term “CBRN defense” to collectively refer to the governance of all domestic agencies involved in CBRN incident response, and to the spectrum of activities tied to that response. In some countries and regional organizations, CBRN response is positioned as defense that spans traditional and nontraditional security challenges, and the capacity to deal with CBRN threats is being raised based on coordination among related agencies, nationally and regionally. In more concrete terms, with regard to chemical threats, there has been growing concern in recent years regarding the use of chemical weapons in civil wars and acts of terrorism, or by state authorities against their own citizens in order to preserve public order or political stability. The key issues pertaining to biological threats are suspected development of biological weapons by certain states, global pandemics, and the risk of misuse or abuse of evolving knowledge and technologies in the life sciences. The main areas of concern surrounding radiological and nuclear threats are risks such as theft and detonation of nuclear weapons, use of improvised nuclear devices (INDs), sabotage and destruction of nuclear power plants and other nuclear facilities, and terrorist use of radiological dispersion devices (RDDs).