Japan Self-Defense Forces' Overseas Dispatch Operations in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management

e Fukushima Nuclearand Crisis Accident Management e Fukushima The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. September, 2012 e Sasakawa Peace Foundation Foreword This report is the culmination of a research project titled ”Assessment: Japan-US Response to the Fukushima Crisis,” which the Sasakawa Peace Foundation launched in July 2011. The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that resulted from the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, involved the dispersion and spread of radioactive materials, and thus from both the political and economic perspectives, the accident became not only an issue for Japan itself but also an issue requiring international crisis management. Because nuclear plants can become the target of nuclear terrorism, problems related to such facilities are directly connected to security issues. However, the policymaking of the Japanese government and Japan-US coordination in response to the Fukushima crisis was not implemented smoothly. This research project was premised upon the belief that it is extremely important for the future of the Japan-US relationship to draw lessons from the recent crisis and use that to deepen bilateral cooperation. The objective of this project was thus to review and analyze the lessons that can be drawn from US and Japanese responses to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and on the basis of these assessments, to contribute to enhancing the Japan-US alliance’s nuclear crisis management capabilities, including its ability to respond to nuclear terrorism. -

Billboard 1978-05-27

031ÿJÚcö7lliloi335U7d SPOTLIG B DALY 50 GRE.SG>=NT T HARTFJKJ CT UolOo 08120 NEWSPAPER i $1.95 A Billboard Publication The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly May 27, 1978 (U.S.) Japanese Production Tax Credit 13 N.Y. DEALERS HIT On Returns Fania In Court i In Strong Comeback 3y HARUHIKO FUKUHARA Stretched? TOKYO -March figures for By MILDRED HALL To Fight Piracy record and tape production in Japan WASHINGTON -The House NBC Opting underscore an accelerating pace of Ways and Means Committee has re- By AGUSTIN GURZA industry recovery after last year's ported out a bill to permit a record LOS ANGELES -In one of the die appointing results. manufacturer to exclude from tax- `AUDIO VIDISK' most militant actions taken by a Disks scored a 16% increase in able gross income the amount at- For TRAC 7 record label against the sale of pi- quantity and a 20% increase in value tributable to record returns made NOW EMERGES By DOUG HALL rated product at the retail level, over last year's March figures. And within 41/2 months after the close of By STEPHEN TRAIMAN Fania Records filed suit Wednesday NEW YORK -What has been tales exceeded those figures with a his taxable year. NEW YORK -Long anticipated, (17) in New York State Supreme held to be the radio industry's main 5S% quantity increase and a 39% Under present law, sellers of cer- is the the "audio videodisk" at point Court against 13 New York area re- hope against total dominance of rat- value increase, reports the Japan tain merchandise -recordings, pa- of test marketing. -

Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History

3 ASIAN HISTORY Porter & Porter and the American Occupation II War World on Reflections Japanese Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The Asian History series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hägerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Members Roger Greatrex, Lund University Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University David Henley, Leiden University Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: 1938 Propaganda poster “Good Friends in Three Countries” celebrating the Anti-Comintern Pact Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 259 8 e-isbn 978 90 4853 263 6 doi 10.5117/9789462982598 nur 692 © Edgar A. Porter & Ran Ying Porter / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Travel and Expenses Reference Guide

Travel Authorization and Expense Reports Reference Guide Travel Authorization and Expense Reports Reference Guide Table of Contents Expense Users .......................................................................................................2 View Expense User Profile ................................................................................................4 Create Travel Authorization ...............................................................................................5 Default Location Lookup …………………………………………………………………………7 Modify Travel Authorization .............................................................................................16 Submit Travel Authorization .............................................................................................19 Cancel Travel Authorization .............................................................................................20 Delete Travel Authorization..............................................................................................21 View Travel Authorization ................................................................................................22 Create Expense Report ...................................................................................................23 Modify Expense Report....................................................................................................29 Submit Expense Report ...................................................................................................32 Delete Expense -

Japan's New Defense Establishment

JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT: INSTITUTIONS, CAPABILITIES, AND IMPLICATIONS Yuki Tatsumi and Andrew L. Oros Editors March 2007 ii | JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT Copyright ©2007 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-5-7 Photos by US Government and Ministry of Defense in Japan. Cover design by Rock Creek Creative. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org YUKI TATSUMI AND ANDREW L. OROS | iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................... v Preface ............................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements...........................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: JAPAN’S EVOLVING DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT .......................... 9 CHAPTER 2: SELF DEFENSE FORCES TODAY— BEYOND AN EXCLUSIVELY DEFENSE –ORIENTED POSTURE? ........................... 23 CHAPTER 3: THE LEGAL AND POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE SELF-DEFENSE FORCES’ OVERSEAS DEPLOYMENTS ......................................... 47 CHAPTER 4: THE UNITED STATES AND “ALLIANCE” ROLE IN JAPAN’S -

The Participation of Small States at the Summer Olympic Games

ISLANDS AND SMALL STATES INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF MALTA, MSIDA, MALTA OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON ISLANDS AND SMALL STATES ISSN 1024-6282 Number: 2021/01 THE PARTICIPATION OF SMALL STATES AT THE SUMMER OLYMPIC GAMES Kevin Joseph Azzopardi More information about the series of occasional paper can be obtained from the Islands and Small States Institute, University of Malta. Tel: 356-21344879, email: [email protected]. THE PARTICIPATION OF SMALL STATES AT THE SUMMER OLYMPIC GAMES Kevin Joseph Azzopardi * 1. Introduction Despite having gone through a marathon 18 days full of events against all odds due to the pandemic, the glamour of the Summer Olympic Games lived on as the entire world got together in a true show of force and unity with athletes battling it out to the least shot, millimetre and point to return back home as Olympic heroes. The starting lists and medals’ table have, as in previous editions, served as an ideal platform for the traditional powerhouses in world sport to further demonstrate their dominance with a few surprises making the headlines from time to time. Ever since the inaugural edition of the Games for the Small States of Europe (GSSE) held in 1985 in San Marino, this biannual event became a benchmark for the participating countries to gauge their progress against other similar countries whose population is less than 1 million inhabitants. As per Table 1, if the same model were to be applied across the globe at Olympic level, 48 countries would fit in the bill for such a comparative exercise with Cyprus’ population, one of the founding members of the GSSE, now increasing to 1.2 million. -

Strategic Yet Strained

INTRODUCTION | i STRATEGIC YET STRAINED US FORCE REALIGNMENT IN JAPAN AND ITS EFFECTS ON OKINAWA Yuki Tatsumi, Editor September 2008 ii | STRATEGIC YET STRAINED Copyright ©2008 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-8-1 Photos from the US Government Cover design by Rock Creek Creative All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms............................................................................................................. v Preface ..............................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements............................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Yuki Tatsumi and Arthur Lord SECTION I: THE CONTEXT CHAPTER 1: THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW OF THE UNITED STATES: “REDUCE, MAINTAIN, AND ENHANCE”............................................................... 13 Derek J. Mitchell CHAPTER 2: THE US STRATEGY BEYOND THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW ...... 25 Tsuneo “Nabe” Watanabe CHAPTER 3: THE LEGACY OF PRIME MINISTER KOIZUMI’S JAPANESE FOREIGN POLICY: AN ASSESSMENT ................................................................... -

Perdiemoutsideusnov1 05

Creighton University - Outside CONUS Meal Per Diem Effective Nov 1, 2005 Please check on CU Website/AP Information for current version/rates. Daily Effective Location Max Rate Date AFGHANISTAN KABUL 32 8/1/2003 [OTHER] 12 8/1/2003 ALASKA ADAK 63 7/1/2003 ANCHORAGE [INCL NAV RES] 05/01 - 09/15 71 6/1/2004 09/16 - 04/30 65 6/1/2004 BARROW 76 5/1/2002 BETHEL 62 6/1/2004 BETTLES 50 10/1/2004 CLEAR AB 44 9/1/2001 COLD BAY 58 5/1/2002 COLDFOOT 57 10/1/1999 COPPER CENTER 05/16 - 09/15 50 7/1/2003 09/16 - 05/15 50 7/1/2003 CORDOVA 05/01 - 09/30 59 4/1/2005 10/01 - 04/30 58 4/1/2005 CRAIG 04/15 - 09/14 51 4/1/2005 09/15 - 04/14 49 4/1/2005 DEADHORSE 54 5/1/2002 DELTA JUNCTION 60 6/1/2004 DENALI NATIONAL PARK 06/01 - 08/31 48 4/1/2005 09/01 - 05/31 46 4/1/2005 DILLINGHAM 55 6/1/2004 DUTCH HARBOR-UNALASKA 58 4/1/2005 perdiemoutsideusnov1 05 64 Daily Effective Location Max Rate Date ALASKA (con't) EARECKSON AIR STATION 44 9/1/2001 EIELSON AFB 05/01 - 09/15 70 6/1/2004 09/16 - 04/30 63 6/1/2004 ELMENDORF AFB 05/01 - 09/15 71 6/1/2004 09/16 - 04/30 65 6/1/2004 FAIRBANKS 05/01 - 09/15 70 6/1/2004 09/16 - 04/30 63 6/1/2004 FOOTLOOSE 14 6/1/2002 FT. -

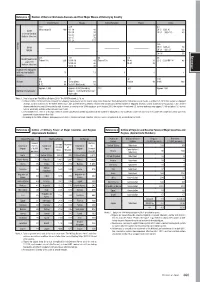

460 Reference

Reference 1 Number of Nuclear Warheads Arsenals and Their Major Means of Delivery by Country United States Russia United Kingdom France China 400 334 60 Minuteman III 400 SS-18 46 DF-5 CSS-4 20 ICBM ( ) SS-19 30 DF-31(CSS-10) 40 (Intercontinental ― ― SS-25 63 Ballistic Missiles) SS-27 78 RS-24 117 Missiles 148 IRBM DF-4(CSS-3) 10 ― ― ― ― MRBM DF-21(CSS-5) 122 DF-26 30 Reference 336 192 48 64 48 SLBM (Submarine Trident D-5 336 SS-N-18 48 Trident D-5 48 M-45 16 JL-2 CSS-NX-14 48 Launched ( ) SS-N-23 96 M-51 48 Ballistic Missiles) SS-N-32 48 Submarines equipped with nuclear ballistic 14 13 4 4 4 missiles 66 76 40 100 Aircraft B-2 20 Tu-95 (Bear) 60 ― Rafale 40 H-6K 100 B-52 46 Tu-160 (Blackjack) 16 Approx. 3,800 Approx. 4,350 (including 215 300 Approx. 280 Number of warheads Approx. 1,830 tactical nuclear warheads) Notes: 1. Data is based on “The Military Balance 2019,” the SIPRI Yearbook 2018, etc. 2. In March 2019, the United States released the following figures based on the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia as of March 1, 2019: the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the United States was 1,365 and the delivery vehicles involved 656 missiles/aircraft; the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for Russia was 1,461 and the delivery vehicles involved 524 missiles/aircraft. However, according to the SIPRI database, as of January 2018, the number of deployed U.S. -

Department of the Navy Commandant of Midshipmen U.S

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY COMMANDANT OF MIDSHIPMEN U.S. NAVAL ACADEMY 101 BUCHANAN ROAD ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND 21402-5100 COMDTMIDNINST 1601.12D APTITUDE 22 Aug 13 COMMANDANT OF MIDSHIPMEN INSTRUCTION 1601.12D Subj: BRIGADE STRIPER ORGANIZATION AND SELECTION PROCEDURES Ref: (a) COMDTMIDNINST 1600.4C (b) USNAINST 1610.3H (c) COMDTMIDNINST 5354.1A (d) COMDTMIDNINST 5350.1C (e) COMDTMIDNINST 1601.10J (f) COMDTMIDNINST 1752.1E 1. Purpose. To provide billet descriptions and describe selection procedures for the Brigade organization. 2. Cancellation. COMDTMIDNINST 1601.12C. This instruction is a complete revision and should be reviewed in its entirety; no special markings appear because changes are extensive. 3. Information a. The Midshipman officer organization with officer mentorship, is responsible for the administration and proper functioning of the Brigade, enhancing the leadership opportunities and experiences available to Midshipmen. b. The Midshipman officer organization shall be divided into two striper sets: First semester and second semester. c. Leadership roles shall be inescapable. To the greatest extent possible, select Midshipmen officers for each semester to maximize leadership opportunities for the largest number of Midshipmen. W. D. BYRNE, JR. Distribution: Non-Mids (Electronically) COMDTMIDNINST 1601.12D 22 Aug 13 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION TOPIC PAGE CHAPTER 1 - ORGANIZATION 101 Brigade Organization..................................1-1 CHAPTER 2 – PRECEDENCE 201 Precedence of Midshipmen..............................2-1 CHAPTER -

Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—The National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2009 Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—the National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010 Tadashi Watanabe University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Watanabe, Tadashi, "Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—the National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 690. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/690 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Japan’s Preventive Strategy: Secure the World – The National Defense Program Guidelines in and after FY 2010 – A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in International Security by Tadashi Watanabe June 2009 Advisors: Paul R. Viotti, Ph.D. Anthony Hayter, Ph.D. Col. Thomas A. Drohan, Ph.D. i ©Copyright by Tadashi Watanabe 2009 All Right Reserved ii Author: Tadashi Watanabe Title: Japan’s Preventive Strategy: Secure the World – The National Defense Program Guidelines in and after FY 2010 – Advisors: Paul R. Viotti, Ph.D. Anthony Hayter, Ph.D. Col. Thomas A. -

U.S.-Japan Alliance Conference: Meeting the Challenge Of

NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE U.S.-Japan Alliance Conference Meeting the Challenge of Amphibious Operations Scott W. Harold, Koichiro Bansho, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Koichi Isobe, Richard L. Simcock II Sponsored by the Government of Japan For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF387 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface In order to explore the origins, development, and implications of Japan’s decision to establish an Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade (ARDB) within the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF), the RAND Corporation convened a public conference on March 6, 2018, at its offices in Santa Monica, California, that brought together leading U.S.