Japan's New Defense Establishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management

e Fukushima Nuclearand Crisis Accident Management e Fukushima The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. September, 2012 e Sasakawa Peace Foundation Foreword This report is the culmination of a research project titled ”Assessment: Japan-US Response to the Fukushima Crisis,” which the Sasakawa Peace Foundation launched in July 2011. The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that resulted from the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, involved the dispersion and spread of radioactive materials, and thus from both the political and economic perspectives, the accident became not only an issue for Japan itself but also an issue requiring international crisis management. Because nuclear plants can become the target of nuclear terrorism, problems related to such facilities are directly connected to security issues. However, the policymaking of the Japanese government and Japan-US coordination in response to the Fukushima crisis was not implemented smoothly. This research project was premised upon the belief that it is extremely important for the future of the Japan-US relationship to draw lessons from the recent crisis and use that to deepen bilateral cooperation. The objective of this project was thus to review and analyze the lessons that can be drawn from US and Japanese responses to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and on the basis of these assessments, to contribute to enhancing the Japan-US alliance’s nuclear crisis management capabilities, including its ability to respond to nuclear terrorism. -

The Dynamics of Public Opinion and Military Alliances Japan‟S Role in the Gulf War and Iraq Invasion

The Dynamics of Public Opinion and Military Alliances Japan‟s Role in the Gulf War and Iraq Invasion Photo credit: Peter Rimar, April 2005 Stian Carstens Bendiksen Master‟s Thesis in Political Science Department of Sociology and Political Science Norwegian University of Science and Technology Spring 2012 1 2 Preface When studying Japanese politics, I found much conflicting research on the role of Japanese public opinion and its influence on policy, especially in regards to how much it affects Japanese politicians. One of the contrasted issues that stood out to me were Japan‟s different responses to the Gulf War and Iraq Invasion, where Japan faced pressure from the US to contribute personnel to the war effort, while the Japanese public opposed dispatching the Japanese Self-Defense Forces overseas. The general aim of this thesis is therefore to weigh the influence of conflicting Japanese public opinion and pressure from the US, on Japanese politicians. I would first and foremost like to thank my advisor for this thesis, Professor Paul Midford. It was initially his Japan and East Asia-focused courses at NTNU that sparked my academic interest for Japan and East-Asia. I owe him a lot for his continued encouragement and support throughout my studies. His thesis advice has been invaluable, and he has made sure that I have adhered to proper methodology, reliable data and thorough analysis. I would also like to thank Natsuyo Ishibashi for reading parts of my paper, providing feedback, and helping me with sources. I would also like to extend my gratitude to my professors at Kanazawa University, Masahiro Kashima, Andrew Beaton, Yoshiomi Saito, Toru Kurata, in addition to my classmates there, whose feedback on my thesis proposal was very helpful. -

Nationalism in Japan's Contemporary Foreign Policy

The London School of Economics and Political Science Nationalism in Japan’s Contemporary Foreign Policy: A Consideration of the Cases of China, North Korea, and India Maiko Kuroki A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, February 2013 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of <88,7630> words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Josh Collins and Greg Demmons. 2 of 3 Abstract Under the Koizumi and Abe administrations, the deterioration of the Japan-China relationship and growing tension between Japan and North Korea were often interpreted as being caused by the rise of nationalism. This thesis aims to explore this question by looking at Japan’s foreign policy in the region and uncovering how political actors manipulated the concept of nationalism in foreign policy discourse. -

The Abduction of Japanese People by North Korea And

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Ritsumeikan Research Repository THE ABDUCTION OF JAPANESE PEOPLE BY NORTH KOREA AND THE DYNAMICS OF JAPANESE DOMESTIC POLITICS AND FOREIGN POLICY: CASE STUDIES OF SHIN KANEMARU AND JUNICHIRO KOIZUMI’S PYONGYANG SUMMIT MEETINGS IN 1990, 2002 AND 2004’S PYONGYANG SUMMIT MEETINGS by PARK Seohee 51114605 March 2017 Master’s Thesis / Independent Final Report Presented to Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Asia Pacific Studies ACKNOLEGEMENTS First and foremost, I praise and thank my Lord, who gives me the opportunity and talent to accomplish this research. You gave me the power to trust in my passion and pursue my dreams. I could never have done this without the faith I have in You, the Almighty. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Yoichiro Sato for your excellent support and guidance. You gave me the will to carry on and never give up in any hardship. Under your great supervision, this work came into existence. Again, I am so grateful for your trust, informative advice, and encouragement. I am deeply thankful and honored to my loving family. My two Mr. Parks and Mrs. Keum for your support, love and trust. Every moment of every day, I thank our Lord Almighty for giving me such a wonderful family. I would like to express my gratitude to Rotary Yoneyama Memorial Foundation, particularly to Mrs. Toshiko Takahashi (and her family), Kunisaki Club, Mr. Minoru Akiyoshi and Mr. -

The Politics of the Futenma Base Issue in Okinawa: Relocation Negotiations in 1995-1997, 2005-2006

Asia-Pacific Policy Papers Series THE POLITICS OF THE FUTENMA BASE ISSUE IN OKINAWA: RELOCATION NEGOTIATIONS IN 1995-1997, 2005-2006 By William L. Brooks Johns Hopkins University The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies tel. 202-663-5812 email: [email protected] The Edwin O. Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies Established in 1984, with the explicit support of the Reischauer family, the Edwin O. Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) actively supports the research and study of trans-Pacific and intra-Asian relations to advance mutual understanding between North-east Asia and the United States. The first Japanese-born and Japanese-speaking US Ambassador to Japan, Edwin O. Reischauer (serv. 1961–66) later served as the center’s Honorary Chair from its founding until 1990. His wife Haru Matsukata Reischauer followed as Honorary Chair from 1991 to 1998. They both exemplified the deep commitment that the Reischauer Center aspires to perpetuate in its scholarly and cultural activities today. Asia-Pacific Policy Papers Series THE POLITICS OF THE FUTENMA BASE ISSUE IN OKINAWA: RELOCATION NEGOTIATIONS IN 1995-1997, 2005-2006 By William L. Brooks William L. Brooks William L. Brooks, an adjunct professor for Japan Studies, has 15 years of experience as head at the Embassy Tokyo’s Office of Media Analysis and Translation unit spanning from 1993 until his retirement in September 2009. Dr. Brooks also served as a senior researcher at the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research and provided the Secretary of State and Washington with policy analysis on Japan (1983-1987, 1990-1993). -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 22, Number 20, May 12, 1995

The book that will unleash a musical revolution- "This Manual is an indispensable contribution to A Manual on the Rudiments of the true history of music and a guide to the inter pretation of music, particularly regarding the tone production of singers and string players alike.... I fully endorse this book and congratulate Lyndon LaRouche on his initiative." Tunin and -Norbert Brainin, founder and firstviolinist, g Amadeus Quartet " ...without any doubt an excellent initiative.It is particularly important to raise the question of Re istration tuning in connection with bel canto technique, g since today's high tuning misplaces all register shifts, and makes it very difficult for a singer to have the sound float above the breath.... What is true for the voice, is also true for instruments." BOOK I: -CarloBergonzi Introduction and Human Singing Voice From Tiananmen Square to Berlin, Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was chosen as the "theme song" of the revolution for human dignity, because Beethoven's work is the highest expression of Classical beauty. Now, for the first time, a Schiller Institute team of musicians and scientists, headed by statesman and philosopher Lyndon H. LaRouche, J r., presents a manual to teach the uni versal principles which underlie the creation of great works of Classical musical art. Book I focuses on the principles of natural beauty $30 plus $4.50 shipping and handling which any work of art must satisfy in order to be Foreign postage: beautiful. First and foremost is the bel canto vocal Canada: $7.00; for each additional book add $1.50 Mexico: $10.00; for each additional book add $3.00 ization of polyphony, sung at the "natural" or South America: $11.75; for each additional book add $5.00 "scientific" tuning which sets middle C at approxi Australia & New Zealand: $12.00; for each additional book add $4.00 Other countries: $10.50; for each additional book add $4.50 mately 256 cycles per second. -

Napsnet Daily Report 19 April, 2004

NAPSNet Daily Report 19 April, 2004 Recommended Citation "NAPSNet Daily Report 19 April, 2004", NAPSNet Daily Report, April 19, 2004, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-daily-report/napsnet-daily-report-19-april-2004/ CONTENTS I. United States 1. PRC-DPRK Secret Talks 2. US Cheney Asia Visit Conclusion 3. ROK Presidential Impeachment 4. KEDO Japan Visit 5. Iraq Japanese Abduction Victims Return Home 6. EU on PRC Arms Ban 7. PRC Tiananmen Square Anniversary Preparation 8. Taiwan World Health Organization Bid II. Japan 1. Japan Hostage Crisis 2. Japan Iraq Troops Dispatch 3. Koizumi on US Presence in Iraq 4. Japan Yasukuni Shrine Controversy III. CanKor E-Clipping Service 1. Issue #160 I. United States 1. PRC-DPRK Secret Talks Agence France-Presse ("NKOREAN LEADER KIM LAUNCHES SECRET VISIT TO CHINA: REPORTS," 04/19/04) reported that DPRK leader Kim Jong-Il has begun a secret visit to the PRC for talks with PRC leaders with the DPRK's nuclear drive high on the agenda, media reports said. A train carrying the reclusive Kim left Pyongyang and entered PRC territory via the DPRK border city of Shinunju late Sunday. Kim is expected to arrive in Beijing on Tuesday or Wednesday for talks with PRC leaders, including President Hu Jintao, Yonhap said, without elaborating on concrete schedules. Agence France-Presse ("NKOREA'S KIM HOLDS TALKS WITH HU IN BEIJING ON NUCLEAR ISSUE," 04/18/04) reported that DPRK leader Kim Jong-Il held talks with President Hu Jintao centred 1 on nuclear issues days after the US cited intelligence that Pyongyang had atomic bombs, reports said. -

The Politics of Telecommunications Reform in Japan

The Politics of Telecommunications Reform in Japan Hidetaka Yoshimatsu The International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development Kitakyushu, Japan 1 Ever since the early 1980s, telecommunications reform has been one of the most critical policy issues in Japan, the United States, and others. The reform often aims to introduce competition into the markets previously dominated by monopolistic company. Given the influence of such a reform on the overall economies and industries, the reform process is likely to accompany the political conflict among politicians, bureaucrats, and private business. This study analyses the telecommunication reform process in Japan, and seeks to contribute to the understanding of the issue of how the Japanese policy-making process is characterised. This issue is one of the most controversial issues regarding Japanese politics and political economy. Early studies of the Japanese political system articulated the bureaucracy-dominant model, seeing the bureaucracy as a dominant role in the policy-making process in Japan. In recent years, quite a few scholars present the pluralistic model of the Japanese political system, arguing that the influence of bureaucracy vis-à-vis politicians has been waning, and that societal actors have played a significant role in shaping economic policy in some cases.1 In order to clarify the nature of the political system, it is a useful way to analyse the development of debates in a particular policy issue, paying attention to the issues of who are involved in the policy-making process with what preferences, and what political interactions are undertaken among the major actors. For this purpose, many scholars have conducted research on specific industrial sectors in Japan (Samuels, 1987; Friedman, 1988; Rosenbluth, 1989; Noble, 1989; Tilton, 1990). -

Brazil, Japan, and Turkey

BRAZIL | 1 BRAZIL, JAPAN, AND TURKEY With articles by Marcos C. de Azambuja Henri J. Barkey Matake Kamiya Edited By Barry M. Blechman September 2009 2 | AZAMBUJA Copyright ©2009 The Henry L. Stimson Center Cover design by Shawn Woodley Photograph on the front cover from the International Atomic Energy Agency All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org BRAZIL | 3 PREFACE I am pleased to present Brazil, Japan, and Turkey, the sixth in a series of Stimson publications addressing questions of how the elimination of nuclear weapons might be achieved. The Stimson project on nuclear security explores the practical dimensions of this critical 21st century debate, to identify both political and technical obstacles that could block the road to “zero,” and to outline how each of these could be removed. Led by Stimson's co-founder and Distinguished Fellow Dr. Barry Blechman, the project provides useful analyses that can help US and world leaders make the elimination of nuclear weapons a realistic and viable option. The series comprises country assessments, published in a total of six different monographs, and a separate volume on such technical issues as verification and enforcement of a disarmament regime, to be published in the fall. This sixth monograph in the series, following volumes on France and the United Kingdom, China and India, Israel and Pakistan, Iran and North Korea, and Russia and the United States, examines three countries without nuclear weapons of their own, but which are nonetheless key states that would need to be engaged constructively in any serious move toward eliminating nuclear weapons. -

JCIE's Annual Report

JAPAN CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE 2001–2003 Annual Report GLOBAL THINKNET CIVILNET POLITICAL EXCHANGE PROGRAM TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Message 2 CivilNet 23 JCIE Activities 5 Promoting Civil Society and Philanthropy 25 The Role of Philanthropy in Postwar U.S.-Japan Global ThinkNet 7 Relations 25 Study and Dialogue Projects 9 GrantCraft—Japanese Video Project 25 APAP Forums and Seminars 9 International Survey Project—The Civil Society Global ThinkNet Conference, Tokyo 10 Sector and NGO Activities in Asia and Europe 26 Intellectual Dialogue on Building Survey on the Status of Exchange Programs Asia’s Tomorrow 10 between the U.S. and Japan 26 A Gender Agenda: Asia-Europe Dialogue 11 Seminar Series with Civil Society Leaders 26 Russia-Japan Policy Dialogue 12 Study Mission on American Philanthropy 27 Cooperation with the Asia Pacific Philanthropy Policy-Oriented Research 13 Consortium (APPC) 27 Vision of Asia Pacific in the 21st Century 13 Facilitating Philanthropic Programs of Asia Pacific and the Global Order Overseas Foundations and Corporations 29 After September 11 13 Levi Strauss Foundation Advised Fund of JCIE 29 The Rise of China and the Changing East Asian Order 14 “Positive Lives Asia” Photo Exhibition Tour 31 Asia Pacific Security Outlook 14 Goldman Sachs Global Leaders Program 31 Force, Intervention, and Sovereignty 15 Lucent Global Science Scholars Program 32 New Perspectives on U.S.-Japan Relations 15 Civil Society and Grassroots-Level Governance for a New Century: Japanese Exchanges 33 Challenges, American Experience 16 A50 Caravan 33 The Future of Governance and the Role Asia Pacific Leadership Program in Tokyo 33 of Politicians 17 Grassroots Network 34 The Transformation of Japanese Communities Miyazaki Prefecture Commemorative and the Emerging Local Agenda 18 Symposiums on Internationalization 34 The Intellectual Infrastructure for East Asian Community-Building 18 Political Exchange Program 35 Support and Cooperation for Research and U.S.-Japan Parliamentary Exchange Program 37 Dialogue 19 U.S. -

Strategic Yet Strained

INTRODUCTION | i STRATEGIC YET STRAINED US FORCE REALIGNMENT IN JAPAN AND ITS EFFECTS ON OKINAWA Yuki Tatsumi, Editor September 2008 ii | STRATEGIC YET STRAINED Copyright ©2008 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-8-1 Photos from the US Government Cover design by Rock Creek Creative All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms............................................................................................................. v Preface ..............................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements............................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Yuki Tatsumi and Arthur Lord SECTION I: THE CONTEXT CHAPTER 1: THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW OF THE UNITED STATES: “REDUCE, MAINTAIN, AND ENHANCE”............................................................... 13 Derek J. Mitchell CHAPTER 2: THE US STRATEGY BEYOND THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW ...... 25 Tsuneo “Nabe” Watanabe CHAPTER 3: THE LEGACY OF PRIME MINISTER KOIZUMI’S JAPANESE FOREIGN POLICY: AN ASSESSMENT ................................................................... -

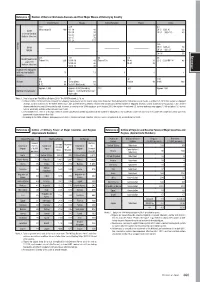

460 Reference

Reference 1 Number of Nuclear Warheads Arsenals and Their Major Means of Delivery by Country United States Russia United Kingdom France China 400 334 60 Minuteman III 400 SS-18 46 DF-5 CSS-4 20 ICBM ( ) SS-19 30 DF-31(CSS-10) 40 (Intercontinental ― ― SS-25 63 Ballistic Missiles) SS-27 78 RS-24 117 Missiles 148 IRBM DF-4(CSS-3) 10 ― ― ― ― MRBM DF-21(CSS-5) 122 DF-26 30 Reference 336 192 48 64 48 SLBM (Submarine Trident D-5 336 SS-N-18 48 Trident D-5 48 M-45 16 JL-2 CSS-NX-14 48 Launched ( ) SS-N-23 96 M-51 48 Ballistic Missiles) SS-N-32 48 Submarines equipped with nuclear ballistic 14 13 4 4 4 missiles 66 76 40 100 Aircraft B-2 20 Tu-95 (Bear) 60 ― Rafale 40 H-6K 100 B-52 46 Tu-160 (Blackjack) 16 Approx. 3,800 Approx. 4,350 (including 215 300 Approx. 280 Number of warheads Approx. 1,830 tactical nuclear warheads) Notes: 1. Data is based on “The Military Balance 2019,” the SIPRI Yearbook 2018, etc. 2. In March 2019, the United States released the following figures based on the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia as of March 1, 2019: the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the United States was 1,365 and the delivery vehicles involved 656 missiles/aircraft; the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for Russia was 1,461 and the delivery vehicles involved 524 missiles/aircraft. However, according to the SIPRI database, as of January 2018, the number of deployed U.S.