An Amphibious Capability in Japan's Self-Defense Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management

e Fukushima Nuclearand Crisis Accident Management e Fukushima The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. September, 2012 e Sasakawa Peace Foundation Foreword This report is the culmination of a research project titled ”Assessment: Japan-US Response to the Fukushima Crisis,” which the Sasakawa Peace Foundation launched in July 2011. The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that resulted from the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, involved the dispersion and spread of radioactive materials, and thus from both the political and economic perspectives, the accident became not only an issue for Japan itself but also an issue requiring international crisis management. Because nuclear plants can become the target of nuclear terrorism, problems related to such facilities are directly connected to security issues. However, the policymaking of the Japanese government and Japan-US coordination in response to the Fukushima crisis was not implemented smoothly. This research project was premised upon the belief that it is extremely important for the future of the Japan-US relationship to draw lessons from the recent crisis and use that to deepen bilateral cooperation. The objective of this project was thus to review and analyze the lessons that can be drawn from US and Japanese responses to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and on the basis of these assessments, to contribute to enhancing the Japan-US alliance’s nuclear crisis management capabilities, including its ability to respond to nuclear terrorism. -

Marines Conclude Multinational Match Lance Cpl

iii marine expeditionary force and marine corps bases japan MAY 27, 2011 WWW.OKINAWA.USMC.MIL Marines conclude multinational match Lance Cpl. Mark W. Stroud OKINAWA MARINE STAFF PUCKAPUNYAL, Australia—The Australian Army Skill at Arms Meeting 2011 came to a close here May 19, end- ing a three-week long marksmanship competition among 13 nations. The annual meeting was designed to test the participants’ combat marksman- ship, build rapport among nations and provide a forum for the discussion of training techniques relating to combat marksmanship. The competition included more than 100 events, allowing participants to test their skills with pistols, light machine guns and assault rifles on varied courses of fire, according to Staff Sgt. Benjamin Robinson, assistant staff noncom- missioned officer-in-charge, Marine Aviation Logistics Squadron 36, Marine Australian Army Maj. Gen. David Morrison, right, commanding general, Forces Command, orders a bayonet charge Aircraft Group 36, 1st Marine Aircraft in Puckapunyal, Australia, during the 2011 Australian Army Skill at Arms Meeting. The charge was carried out by U.S. Wing, III Marine Expeditionary Force. Marines with Marine Shooting Detachment Australia, New Zealand Army soldiers and Australian Army soldiers. The The Marines walked away with a three-week meeting, which ended May 19, pitted military representatives from partner nations in competition in a trophy for their performance during series of combat marksmanship events. Represented nations included Canada, France (French Forces New Caledonia), the matches. Indonesia, Timor Leste, Brunei, Netherlands, United States, Papua New Guinea, New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia, SEE AASAM PG 5 Thailand as well as a contingent of Japanese observers. -

Japan's New Defense Establishment

JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT: INSTITUTIONS, CAPABILITIES, AND IMPLICATIONS Yuki Tatsumi and Andrew L. Oros Editors March 2007 ii | JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT Copyright ©2007 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-5-7 Photos by US Government and Ministry of Defense in Japan. Cover design by Rock Creek Creative. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org YUKI TATSUMI AND ANDREW L. OROS | iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................... v Preface ............................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements...........................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: JAPAN’S EVOLVING DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT .......................... 9 CHAPTER 2: SELF DEFENSE FORCES TODAY— BEYOND AN EXCLUSIVELY DEFENSE –ORIENTED POSTURE? ........................... 23 CHAPTER 3: THE LEGAL AND POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE SELF-DEFENSE FORCES’ OVERSEAS DEPLOYMENTS ......................................... 47 CHAPTER 4: THE UNITED STATES AND “ALLIANCE” ROLE IN JAPAN’S -

Strategic Yet Strained

INTRODUCTION | i STRATEGIC YET STRAINED US FORCE REALIGNMENT IN JAPAN AND ITS EFFECTS ON OKINAWA Yuki Tatsumi, Editor September 2008 ii | STRATEGIC YET STRAINED Copyright ©2008 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-8-1 Photos from the US Government Cover design by Rock Creek Creative All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms............................................................................................................. v Preface ..............................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements............................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Yuki Tatsumi and Arthur Lord SECTION I: THE CONTEXT CHAPTER 1: THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW OF THE UNITED STATES: “REDUCE, MAINTAIN, AND ENHANCE”............................................................... 13 Derek J. Mitchell CHAPTER 2: THE US STRATEGY BEYOND THE GLOBAL POSTURE REVIEW ...... 25 Tsuneo “Nabe” Watanabe CHAPTER 3: THE LEGACY OF PRIME MINISTER KOIZUMI’S JAPANESE FOREIGN POLICY: AN ASSESSMENT ................................................................... -

460 Reference

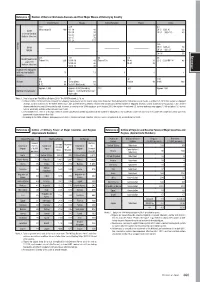

Reference 1 Number of Nuclear Warheads Arsenals and Their Major Means of Delivery by Country United States Russia United Kingdom France China 400 334 60 Minuteman III 400 SS-18 46 DF-5 CSS-4 20 ICBM ( ) SS-19 30 DF-31(CSS-10) 40 (Intercontinental ― ― SS-25 63 Ballistic Missiles) SS-27 78 RS-24 117 Missiles 148 IRBM DF-4(CSS-3) 10 ― ― ― ― MRBM DF-21(CSS-5) 122 DF-26 30 Reference 336 192 48 64 48 SLBM (Submarine Trident D-5 336 SS-N-18 48 Trident D-5 48 M-45 16 JL-2 CSS-NX-14 48 Launched ( ) SS-N-23 96 M-51 48 Ballistic Missiles) SS-N-32 48 Submarines equipped with nuclear ballistic 14 13 4 4 4 missiles 66 76 40 100 Aircraft B-2 20 Tu-95 (Bear) 60 ― Rafale 40 H-6K 100 B-52 46 Tu-160 (Blackjack) 16 Approx. 3,800 Approx. 4,350 (including 215 300 Approx. 280 Number of warheads Approx. 1,830 tactical nuclear warheads) Notes: 1. Data is based on “The Military Balance 2019,” the SIPRI Yearbook 2018, etc. 2. In March 2019, the United States released the following figures based on the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia as of March 1, 2019: the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the United States was 1,365 and the delivery vehicles involved 656 missiles/aircraft; the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for Russia was 1,461 and the delivery vehicles involved 524 missiles/aircraft. However, according to the SIPRI database, as of January 2018, the number of deployed U.S. -

Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—The National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2009 Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—the National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010 Tadashi Watanabe University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Watanabe, Tadashi, "Japan's Preventive Strategy: Secure the World—the National Defense Program Guidelines in and After FY 2010" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 690. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/690 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Japan’s Preventive Strategy: Secure the World – The National Defense Program Guidelines in and after FY 2010 – A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in International Security by Tadashi Watanabe June 2009 Advisors: Paul R. Viotti, Ph.D. Anthony Hayter, Ph.D. Col. Thomas A. Drohan, Ph.D. i ©Copyright by Tadashi Watanabe 2009 All Right Reserved ii Author: Tadashi Watanabe Title: Japan’s Preventive Strategy: Secure the World – The National Defense Program Guidelines in and after FY 2010 – Advisors: Paul R. Viotti, Ph.D. Anthony Hayter, Ph.D. Col. Thomas A. -

U.S.-Japan Alliance Conference: Meeting the Challenge Of

NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE U.S.-Japan Alliance Conference Meeting the Challenge of Amphibious Operations Scott W. Harold, Koichiro Bansho, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Koichi Isobe, Richard L. Simcock II Sponsored by the Government of Japan For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF387 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface In order to explore the origins, development, and implications of Japan’s decision to establish an Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade (ARDB) within the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF), the RAND Corporation convened a public conference on March 6, 2018, at its offices in Santa Monica, California, that brought together leading U.S. -

Newport Paper 38

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 38 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL High Seas Buffer The Taiwan Patrol Force, 1950–1979 NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O L N L U E E G H E T I VIRIBU OR A S CT MARI VI 38 Bruce A. Elleman Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978-1-884733-95-6 is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates High Seas Buffer: The Taiwan Patrol Force, 1950–1979, by Bruce A. Elleman, as an official publication of the College. It is prohibited to use NWC’s logo on any republication of this book without the express, written permission of the Editor, Naval War College Press, or the editor’s designee. -

Reference 1. Major Nuclear Forces

Reference Reference 1. Major Nuclear Forces U.S. Russia U.K. France China 550 508 46 Intercontinental Minuteman III: 500 SS-18: 80 DF-5 (CSS-4): 20 ballistic missiles Peacekeeper: 50 SS-19: 126 — — DF-31 (CSS-9): 6 (ICBMs) SS-25: 254 DF-4 (CSS-3): 20 SS-27: 48 35 IRBMs — — — — DF-3 (CSS-2): 2 MRBMs DF-21 (CSS-5): 33 SRBMs — — — — 725 Missiles 432 252 48 64 12 Trident C-4: 120 SS-N-18: 96 Trident D-5: 48 M-45: 64 JL-1 (CSS-N-3): 12 Submarine Trident D-5: 312 SS-N-19: 60 (SSBN [Nuclear- (SSBN [Nuclear- (SSBN [Nuclear- launched (SSBN [Nuclear- SS-N-23: 96 powered submarines powered submarines powered submarines ballistic missiles powered submarines (SSBN [Nuclear- with ballistic missile with ballistic missile with ballistic missile (SLBMs) with ballistic missile powered submarines payloads]: 4) payloads]: 4) payloads]: 1) payloads]: 14) with ballistic missile payloads]: 15) 114 79 Long-distance B-2: 19 Tu-95 (Bear): 64 — — — (strategic) bombers B-52: 94 Tu-160 (Blackjack): 15 Note: Sources: Military Balance 2008, etc. — 391 — Reference 2. Performance of Major Ballistic and Cruise Missiles Maximum Item Country Name Warhead (yield) Guidance System Remarks range MIRV (170 KT, 335-350 KT or Minuteman III 13,000 Inertial Three-stage solid U.S. 300-475 KT × 3) Peacekeeper 9,600 MIRV (300–475 KT × 10) Inertial Three-stage solid MIRV (1.3 MT × 8, 500 -550 KT × 10 or SS-18 10,500-16,000 Inertial Two-stage liquid 500-750KT × 10) or Single (24MT) Russia MIRV (550 KT × 6 or 500-750 ICBM SS-19 9,000-10,000 Inertial Two-stage liquid KT × 6) SS-25 10,500 Single (550 KT) Inertial + Computer control Three-stage solid SS-27 10,500 Single (550 KT) Inertial + GLONASS Three-stage solid Single (4 MT) or DF-5 (CSS-4) 12,000-13,000 Inertial Two-stage liquid MIRV (150-350 KT × 4-6) China Single (1 MT) or DF-31 (CSS-9) 8,000-14,000 Inertial + Stellar reference Three-stage solid MIRV (20–150 KT × 3–5) Trident C-4 7,400 MIRV (100 KT × 8) Inertial + Stellar reference Three-stage solid U.S. -

Chapter 8 CBRN Defense: Responding to Growing Threats

Chapter 8 CBRN Defense: Responding to Growing Threats n the wake of the Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attacks in Japan in 1994 and 1995, Iand the 9/11 and anthrax mail attacks in the United States in 2001, threats involving the use of chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear materials/ agents have come to be collectively referred to as CBRN threats. This term broadly encompasses not only the traditional concept of NBC attacks—those by nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons—but also terrorist attacks, accidents, or natural disasters. Given these intricacies, this chapter proposes using the term “CBRN defense” to collectively refer to the governance of all domestic agencies involved in CBRN incident response, and to the spectrum of activities tied to that response. In some countries and regional organizations, CBRN response is positioned as defense that spans traditional and nontraditional security challenges, and the capacity to deal with CBRN threats is being raised based on coordination among related agencies, nationally and regionally. In more concrete terms, with regard to chemical threats, there has been growing concern in recent years regarding the use of chemical weapons in civil wars and acts of terrorism, or by state authorities against their own citizens in order to preserve public order or political stability. The key issues pertaining to biological threats are suspected development of biological weapons by certain states, global pandemics, and the risk of misuse or abuse of evolving knowledge and technologies in the life sciences. The main areas of concern surrounding radiological and nuclear threats are risks such as theft and detonation of nuclear weapons, use of improvised nuclear devices (INDs), sabotage and destruction of nuclear power plants and other nuclear facilities, and terrorist use of radiological dispersion devices (RDDs). -

Japan's National Security Policy Infrastructure

INTRODUCTION | i JAPAN’S NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY INFRASTRUCTURE CAN TOKYO MEET WASHINGTON’S EXPECTATION? Yuki Tatsumi November 2008 ii | JAPAN’S NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY INFRASTRUCTURE Copyright ©2008 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-9-X Photos by the Ministry of Defense in Japan and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force Cover design by Rock Creek Creative. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org YUKI TATSUMI | iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms............................................................................................................ iv Preface ................................................................................................................ vi Acknowledgements............................................................................................ vii INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: EVOLUTION OF JAPANESE NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY .............. 11 CHAPTER 2: CIVILIAN INSTITUTIONS ................................................................ 33 CHAPTER 3: UNIFORM INSTITUTIONS................................................................ 65 CHAPTER 4: THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY.................................................. 97 CHAPTER -

Japan Self-Defense Forces' Overseas Dispatch Operations in The

Japan Self-Defense Forces’ Overseas Dispatch Operations in the 1990s: Effective International Actors? Garren Mulloy A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Newcastle University School of Geography, Politics and Sociology 2011 Abstract Garren Mulloy This thesis investigates Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) overseas deployment operations (ODO) of the 1990s to evaluate whether the JSDF were effective international actors. This study fills a significant gap in extant literature concerning operational effectiveness, most studies having concentrated upon constitutionality and legality. This study places operational evaluations within the context of international actors during the vital decade of the 1990s, and within the broader context of Japanese security policies. JSDF performance is studied in four mission variants: UN peacekeeping, allied support, humanitarian assistance, and disaster relief operations. A four-stage analytical framework is utilised, evaluating JSDF effectiveness, efficiency, and quality, comparing between missions, mission variants, and with other international actors, thereby cross-referencing evaluations and analyses. The historical development of the JSDF profoundly affected their configuration and ability to conduct operations, not least the mechanisms of civilian control, the constitution, and mediated passage of ODO-related laws. However, these factors have not prevented the development of significant JSDF ODO-capabilities, and their development is traced through the target decade, and linked to the successful completion of post-2001 operations in Iraq and East Timor. It is found that although JSDF ODO in the 1990s provided effective, quality services, operational efficiency was frequently compromised by lack of investment in key capabilities and limited scales of dispatch, despite the relative cost-effectiveness of ODO.