Language Luganda 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

African Studies in Russia

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE FOR AFRICAN STUDIES Editorial Board . A.M. VASILIEV (Editor-in-Chief) I.O. ABRAMOVA , D.M. BONDARENKO, An.N. IVANOV, N.A. KSENOFONTOVA, V.G. SHUBIN, G.M. SIDOROVA AFRICAN STUDIES Translation from Russian IN RUSSIA Yearbook 2003–2007 ISBN 978–5–91298–047–3 © ɂɧɫɬɢɬɭɬȺɮɪɢɤɢɊȺɇ, 2009 © Ʉɨɥɥɟɤɬɢɜɚɜɬɨɪɨɜ, 2009. MOSCOW 2009 Anatoly Savateyev. African Civilization in the Modern World ................................182 CONTENTS Natalia Ksenofontova. Gender and Power ................................................................190 SOCIAL AND POLITICAL PROBLEMS Dmitri Bondarenko. Visiting the Oba of Benin ................................................................203 Yury Potyomkin. Nepad, a Project of Hope? ................................................................5 Natalia Krylova. Russian Women and the Sharia: Drama in Women’s Quarters ................................................................................................209 Boris Runov. Intellectual Foundations for Development: Agenda for Sub-Saharan Africa ………………..………………… 22 Svetlana Prozhogina. Difficulties of Cultural Boundaries: “Break-Up”, “Border” or Inevitable “Transition”? Literary French Yury Skubko. South African Science after Apartheid Modern Language of the Arab World ................................................................222 Scientific and Technological Potential of the RSA ………………. 35 Nelli Gromova. The Ethno-Linguistic Situation in Tanzania ................................235 Veronika Usacheva. Mass Media in -

The Classification of the Bantu Languages of Tanzania

i lIMFORIVIATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document h^i(^|eeh used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the qriginal submitted. ■ The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. I.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Mining Page(s)". IfJt was'possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are^spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you'complete continuity. 2. When an.image.on the film is obliterated with li large round black mark, it . is an if}dication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during, exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing' or chart, etc., was part of the material being V- photographed the photographer ' followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to .continue photoing fronTleft to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued, again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until . complete. " - 4. The majority of usefs indicate that the textual content is, of greatest value, ■however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from .'"photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

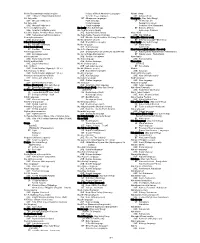

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) K-TEA (Achievement test) Kʻa-la-kʻun-lun kung lu (China and Pakistan) USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Karakoram Highway (China and Pakistan) K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) K-theory Ka Lae o Kilauea (Hawaii) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) [QA612.33] USE Kilauea Point (Hawaii) K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) BT Algebraic topology Ka Lang (Vietnamese people) UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) Homology theory USE Giẻ Triêng (Vietnamese people) K9 (Fictitious character) NT Whitehead groups Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) (May Subd Geog) K 37 (Military aircraft) K. Tzetnik Award in Holocaust Literature [DS528.2.K2] USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) UF Ka-Tzetnik Award UF Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) K 98 k (Rifle) Peras Ḳ. Tseṭniḳ BT Ethnology—Burma USE Mauser K98k rifle Peras Ḳatseṭniḳ ʾKa nao dialect (May Subd Geog) K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 BT Literary prizes—Israel BT China—Languages USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 K2 (Pakistan : Mountain) Hmong language K.A. Lind Honorary Award UF Dapsang (Pakistan) Ka nō (Burmese people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Godwin Austen, Mount (Pakistan) USE Tha noʹ (Burmese people) K.A. Linds hederspris Gogir Feng (Pakistan) Ka Rang (Southeast Asian people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Mount Godwin Austen (Pakistan) USE Sedang (Southeast Asian people) K-ABC (Intelligence test) BT Mountains—Pakistan Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children Karakoram Range USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine K-B Bridge (Palau) K2 (Drug) Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Synthetic marijuana Ka-taw K-BIT (Intelligence test) K3 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Takraw USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test USE Broad Peak (Pakistan and China) Ka Tawng Luang (Southeast Asian people) K. -

African Linguistics Across the Disciplines

African linguistics across the disciplines Selected papers from the 48th Annual Conference on African Linguistics Edited by Samson Lotven Silvina Bongiovanni Phillip Weirich Robert Botne Samuel Gyasi Obeng language Contemporary African Linguistics 5 science press Contemporary African Linguistics Editors: Akinbiyi Akinlabi, Laura J. Downing In this series: 1. Payne, Doris L., Sara Pacchiarotti & Mokaya Bosire (eds.). Diversity in African languages: Selected papers from the 46th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. 2. Persohn, Bastian. The verb in Nyakyusa: A focus on tense, aspect and modality. 3. Kandybowicz, Jason, Travis Major & Harold Torrence (eds.). African linguistics on the prairie: Selected papers from the 45th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. 4. Clem, Emily, Peter Jenks & Hannah Sande (eds.). Theory and description in African Linguistics: Selected papers from the 47th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. 5. Lotven, Samson, Silvina Bongiovanni, Phillip Weirich, Robert Botne & Samuel Gyasi Obeng (eds.). African linguistics across the disciplines: Selected papers from the 48th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. ISSN: 2511-7726 African linguistics across the disciplines Selected papers from the 48th Annual Conference on African Linguistics Edited by Samson Lotven Silvina Bongiovanni Phillip Weirich Robert Botne Samuel Gyasi Obeng language science press Lotven, Samson, Silvina Bongiovanni, Phillip Weirich, Robert Botne & Samuel Gyasi Obeng (ed.). 2019. African linguistics across the disciplines: Selected papers -

Aspectual Classes of Verbs in Nyamwezi

Aspectual Classes of Verbs in Nyamwezi ASPECTUAL CLASSES OF VERBS IN NYAMWEZI Ponsiano Sawaka Kanijo To my mother Margreth Nyamizi Bernard Doctoral dissertation in African Languages, University of Gothenburg October 25, 2019 Dissertation edition © 2019 Ponsiano Sawaka Kanijo Cover design: Thomas Ekholm Printed by GU Interntryckeri, University of Gothenburg, 2019 ISBN: 978-91-7833-652-4 (PRINT) ISBN: 978-91-7833-653-1 (PDF) Link to E-publication: http://hdl.handle.net/2077/60370 Distribution: Department of Languages and Literatures, University of Gothenburg, Box 200, SE-40530, Göteborg The picture of a mango tree on the cover represents the original name of Tabora region, an area where Nyamwezi is spoken. This area was originally called Unyanyembe (from the Nyamwezi word inyeembé ‘mango’) due to the huge ancient mango trees, which were grown by long-distance traders (Joynson-Hicks, 1998, p. 136). TITLE: Aspectual classes of Verbs in Nyamwezi AUTHOR: Ponsiano Sawaka Kanijo LANGUAGE: English DISTRIBUTION: Department of Languages and Literatures, University of Gothenburg, Box 200, SE_40530 Göteborg ISBN: 978-91-7833-652-4 (PRINT) ISBN: 978-91-7833-653-1 (PDF) http://hdl.handle.net/2077/60370 Abstract This dissertation deals with the classification of verbs in Nyamwezi, a Bantu language spoken in central-west Tanzania. The major aims of this study have been twofold: first, to classify Nyamwezi verbs into different aspectual classes, and second, to present a variety of tests that were used as evidence for a verb’s aspectual class membership. The data for the analysis and classification of verbs in this study were collected using a variety of fieldwork techniques mostly direct elicitation (sentence translation from questionnaires) and contextual elicitation (testing the acceptability of a construction based on a range of imaginary discourse contexts provided to the consultant). -

Common Characteristics in Sukuma-Nyamwezi Transitional Dialects

The University of Dodoma University of Dodoma Institutional Repository http://repository.udom.ac.tz Humanities Master Dissertations 2015 Common characteristics in Sukuma-Nyamwezi transitional dialects. Joilet, Kamil The University of Dodoma Joilet, K. (2015). Common characteristics in Sukuma-Nyamwezi transitional dialects. Dodoma: The University of Dodoma. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12661/732 Downloaded from UDOM Institutional Repository at The University of Dodoma, an open access institutional repository. COMMON CHARACTERISTICS IN SUKUMA-NYAMWEZI TRANSITIONAL DIALECTS BY Kamil Joilet A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master Degree of Arts in Linguistics in the University of Dodoma University of Dodoma October, 2015 CERTIFICATION The undersigned certifies that he has read and hereby recommends for acceptance by The University of Dodoma a dissertation entitled: Common Characteristics in Sukuma-Nyamwezi Transitional Dialects. In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics of the University of Dodoma. ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Dr.Stanislav Beletskiy (SUPERVISOR) Date: ------------------------------------------------------------ i DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT I, Joilet Kamil, declare that this thesis is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for a similar or any other degree award. Signature:………………… … ………………..…… No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the author or the University of Dodoma. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would first and foremost like to record all praises and glory to the Almighty God for the strength and courage which he bestowed upon me during my entire education endeavor. -

A Comparative Grammar of the South African Bantu Language, Comprising Those of Zanzibar, Mozambique, the Zambesi, Kafirland

A COMPARATIYE GRAMMAR OF THE SOUIH-AfRICAN BANIU LANGUAGES f^SlOBi-o.-Klway BOUGHT WITH THE INCO FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT THE GIFT OF m^nv^ M. Sage r89i f 1924 077 077 612 -3j 3^. no paDE^d ajtsJ iHQ\f nosjad ana hbih ajoin :o /907 ;Cq papaan sapog pa^tiEM jfx'aanasqB s,j3 -iiojjoq Snunp njn;aj nam joj apem s^nam -a3uBJiB JO 'X!jBaq;i aqi 0} paujtuaj aq Pinoqs . - spouad ssaaaj Saunp/U t\ I' jT^HjiHr*''* ^on sifoog papaan ^ •sjaqio jCq papaan ^on, sj 3iooq B H3IIM. 'saSaj .-TAud iBMauaj q^M*. 's>[aaM. oM% zo} samn -^6a 3Ag paMojiB aJB BJaMojjoq pajirajl •a^Bin aq ' • pin6qs ^sanbaj lEiaads , B s3[aaM OAv; pno/Caq papaan naqM '. a^qtssod _ SB igoos SB panan^aj aq pjnoqs japBJBqo x^-ia -naS B JO siBOipouad; ' -sja^oj -joq lie o| S5[aa4i jnoj 01 paiimii ajB qajBas .31 JO nofionjisni joj asn nt ^on sqooq nv 'U3>|e^sGAiaiun|0A sm:^ u9i(Afi sm.oi|s ovep am. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924077077612 A COMPARATIVE GRAMMAR OF THE SOUTH-AFRICAN BANTU LANGUAGES. ST-AUSTIN'S PRESS, DESCLfiE, DE BROUWER AND CO., BRUGKS. SOUTH-AFRICA REFERENCE MAP TO ACCOMPANY THE Comparative Grammar OF THE South -African Bantu Languages BT J.TORREND, S.J. N. B. The names -printed in red are those of the languages more particularly dealt with in this work .Non-Bantu Lan§ua§es; Wi Bantu intermixed with non- Bantu Lan^ua^es., aoi,ie[» S* -^u^ti.'ti A comparative" GRAMMAR OF THE SOUTH-AFRICAN BANTU LANGUAGES COMPRISING THOSE OF ZANZIBAR, MOZAMBIQUE, THE ZAMBEZI, KAFIRLAND, BENGUELA, ANGOLA, THE CONGO, THE OGOWE, THE CAMEROONS, THE LAKE REGION, ETC. -

Thesis Reference

Thesis Ressources plurilingues en classe de FLE: représentations, normes et pratiques pédagogiques dans le contexte sociolinguistique tanzanien LULANDALA, Mussa Julius Abstract L'enseignement du français langue étrangère en Tanzanie s'inscrit dans un contexte multilingue où le swahili, l'anglais et plus de 120 langues des communautés ethniques existent. Pour la majorité des élèves tanzaniens du cycle secondaire, le français est leur quatrième langue. C'est donc un contexte qui constitue un terrain particulièrement intéressant pour l'exploitation des ressources plurilingues pour l'appropriation du FLE. Inspirée d'une approche socio-didactique, et à la lumière des données vidéo, orales, et écrites, la présente étude aborde des questions de représentations et de pratiques vis-à-vis des langues et des ressources bi-plurilingues. En particulier, l'étude a mis en évidence que la majorité des sujets sont, à des degrés variables de connaissance, exposés à quatre langues, à savoir une LCE, le swahili, l'anglais et le français; le swahili étant la langue la plus partagée par les partenaires de la classe de FLE. Compte tenu de la nature plurilingue, de la relative asymétrie de la classe des débutants en FLE et des facteurs sociaux externes à la classe de langue; nous [...] Reference LULANDALA, Mussa Julius. Ressources plurilingues en classe de FLE: représentations, normes et pratiques pédagogiques dans le contexte sociolinguistique tanzanien. Thèse de doctorat : Univ. Genève, 2015, no. L. 838 URN : urn:nbn:ch:unige-771838 DOI : 10.13097/archive-ouverte/unige:77183 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:77183 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. -

The Diplomatist's Handbook for Africa (1897)

mwir ~ fek : ^ 17 DEC, 1941 iihiv: _ja. _ j _ Klasnurr 7 pa^sa\ Register. - ^ — THE DIPLOMATIST'S HANDBOOK FOR AFRICA BY COUNT CHARLES KINSKY. Semper aliquid novi ex Africa. WITH A POLITICAL MAP. LONDON KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & Co. Lim. PATERNOSTER HOUSE, CHARING CROSS ROAD. 1897. All rights reserved. and R. court-typography Charles Prochaska, Teschen. Preface, Africa, with its wild, virginal hunting fields and its heart of mystery, that has still to yield up its secrets to the explorer, has at all times excited a lively interest in me. Many of my friends and acquaintances have made it the scene of their travels or the field for their exertions, more than one to find there, alas an untimely grave. The various reports having served to strengthen my con- viction in the ultimate and supreme mission of the dark continent as the source from which exhausted Europe would draw that vitality necessary for its future nourishment, the range of my enquiry naturally became increased, and I missed no opportunity to collect and note down thoroughly reliable information. Soon afterwards it became my duty to make myself acquainted with African affairs, and I also seized this occasion to enrich my knowledge and complete my notes. And here I cannot refrain from putting on record my in- debtedness, first and foremost, to my valued friend, Professor Dr. Paulitschke, Private Lecturer at the Vienna University. It is to his clear and comprehensive lectures, based upon concise and intimate knowledge, as well as to the study of the litera- ture recommended by him, that I owe an accurate and reliable insight into the social and political relations prevailing in Africa. -

LCSH Section N

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine Indians of North America—Languages Na'ami sheep USE Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine West (U.S.)—Languages USE Awassi sheep N-3 fatty acids NT Athapascan languages Naamyam (May Subd Geog) USE Omega-3 fatty acids Eyak language UF Di shui nan yin N-6 fatty acids Haida language Guangdong nan yin USE Omega-6 fatty acids Tlingit language Southern tone (Naamyam) N.113 (Jet fighter plane) Na family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ballads, Chinese USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) Na Guardis Island (Spain) Folk songs, Chinese N.A.M.A. (Native American Music Awards) USE Guardia Island (Spain) Naar, Wadi USE Native American Music Awards Na Hang Nature Reserve (Vietnam) USE Nār, Wādī an N-acetylhomotaurine USE Khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Nà Hang (Vietnam) Naʻar (The Hebrew word) USE Acamprosate Na-hsi (Chinese people) BT Hebrew language—Etymology N Bar N Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi (Chinese people) Naar family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ranches—Montana Na-hsi language UF Nahar family N Bar Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi language Narr family BT Ranches—Montana Na Ih Es (Apache rite) Naardermeer (Netherlands : Reserve) N-benzylpiperazine USE Changing Woman Ceremony (Apache rite) UF Natuurgebied Naardermeer (Netherlands) USE Benzylpiperazine Na-ion rechargeable batteries BT Natural areas—Netherlands n-body problem USE Sodium ion batteries Naas family USE Many-body problem Na-Kara language USE Nassau family N-butyl methacrylate USE Nakara language Naassenes USE Butyl methacrylate Ná Kê (Asian people) [BT1437] N.C. 12 (N.C.) USE Lati (Asian people) BT Gnosticism USE North Carolina Highway 12 (N.C.) Na-khi (Chinese people) Nāatas N.C. -

*‡Table 6. Languages

T6 Table[6.[Languages T6 T6 DeweyT6iDecima Tablel[iClassification6.[Languages T6 *‡Table 6. Languages The following notation is never used alone, but may be used with those numbers from the schedules and other tables to which the classifier is instructed to add notation from Table 6, e.g., translations of the Bible (220.5) into Dutch (—3931 in this table): 220.53931; regions (notation —175 from Table 2) where Spanish language (—61 in this table) predominates: Table 2 notation 17561. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number Unless there is specific provision for the old or middle form of a modern language, class these forms with the modern language, e.g., Old High German —31, but Old English —29 Unless there is specific provision for a dialect of a language, class the dialect with the language, e.g., American English dialects —21, but Swiss-German dialect —35 Unless there is a specific provision for a pidgin, creole, or mixed language, class it with the source language from which more of its vocabulary comes than from its other source language(s), e.g., Crioulo language —69, but Papiamento —68. If in doubt, prefer the language coming last in Table 6, e.g., Michif —97323 (not —41) The numbers in this table do not necessarily correspond exactly to the numbers used for individual languages in 420–490 and in 810–890. For example, although the base number for English in 420–490 is 42, the number for English in Table 6 is —21, not —2 (Option A: To give local emphasis and a shorter number to a specific language, place it first by use of a letter or other symbol, e.g., Arabic language 6_A [preceding 6_1].