Forms and Functions of Codeswitching to Hindi/Urdu in Indian English and Pakistani English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Forms of Seeking Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language

THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 T.U. Reg. No.:9-2-540-164-2010 Date of Approval Thesis Fourth Semester Examination Proposal: 18/12/2017 Exam Roll No.: 28710094/072 Date of Submission: 30/05/2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that to the best of my knowledge this thesis is original; no part of it was earlier submitted for the candidate of research degree to any university. Date: ..…………………… Jyoti Kaushal i RECOMMENDATION FOR ACCEPTANCE This is to certify that Miss Jyoti Kaushal has prepared this thesis entitled The Forms of Seeking, Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language under my guidance and supervision I recommend this thesis for acceptance Date: ………………………… Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav Reader Department of English Education Faculty of Education TU, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal ii APPROVAL FOR THE RESEARCH This thesis has been recommended for evaluation from the following Research Guidance Committee: Signature Dr. Prem Phyak _______________ Lecturer & Head Chairperson Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav (Supervisor) _______________ Reader Member Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. -

Genealogical Classification of New Indo-Aryan Languages and Lexicostatistics

Anton I. Kogan Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Russia, Moscow); [email protected] Genealogical classification of New Indo-Aryan languages and lexicostatistics Genetic relations among Indo-Aryan languages are still unclear. Existing classifications are often intuitive and do not rest upon rigorous criteria. In the present article an attempt is made to create a classification of New Indo-Aryan languages, based on up-to-date lexicosta- tistical data. The comparative analysis of the resulting genealogical tree and traditional clas- sifications allows the author to draw conclusions about the most probable genealogy of the Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords: Indo-Aryan languages, language classification, lexicostatistics, glottochronology. The Indo-Aryan group is one of the few groups of Indo-European languages, if not the only one, for which no classification based on rigorous genetic criteria has been suggested thus far. The cause of such a situation is neither lack of data, nor even the low level of its historical in- terpretation, but rather the existence of certain prejudices which are widespread among In- dologists. One of them is the belief that real genetic relations between the Indo-Aryan lan- guages cannot be clarified because these languages form a dialect continuum. Such an argu- ment can hardly seem convincing to a comparative linguist, since dialect continuum is by no means a unique phenomenon: it is characteristic of many regions, including those where Indo- European languages are spoken, e.g. the Slavic and Romance-speaking areas. Since genealogi- cal classifications of Slavic and Romance languages do exist, there is no reason to believe that the taxonomy of Indo-Aryan languages cannot be established. -

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE. The Court strongly prefers to use live interpreters in the courtrooms whenever possible. However, when the Court can’t find live interpreters, we sometimes use Language Line, a national telephone service supplying interpreters for most languages on the planet almost immediately. The number for that service is 1-800-874-9426. Contact Circuit Administration at 605-367-5920 for the Court’s account number and authorization codes. AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE/DEAF INTERPRETATION Minnehaha County in the 2nd Judicial Circuit uses a combination of local, highly credentialed ASL/Deaf interpretation providers including Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD), Interpreter Services Inc. (ISI), and highly qualified freelancers for the courts in Sioux Falls, Minnehaha County, and Canton, Lincoln County. We are also happy to make court video units available to any other courts to access these interpreters from Sioux Falls (although many providers have their own video units now). The State of South Dakota has also adopted certification requirements for ASL/deaf interpretation “in a legal setting” in 2006. The following link published by the State Department of Human Services/ Division of Rehabilitative Services lists all the certified interpreters in South Dakota and their certification levels, and provides a lot of other information on deaf interpretation requirements and services in South Dakota. DHS Deaf Services AFRICAN DIALECTS A number of the residents of the 2nd Judicial Circuit speak relatively obscure African dialects. For court staff, attorneys, and the public, this list may be of some assistance in confirming the spelling and country of origin of some of those rare African dialects. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) K-TEA (Achievement test) Kʻa-la-kʻun-lun kung lu (China and Pakistan) USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Karakoram Highway (China and Pakistan) K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) K-theory Ka Lae o Kilauea (Hawaii) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) [QA612.33] USE Kilauea Point (Hawaii) K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) BT Algebraic topology Ka Lang (Vietnamese people) UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) Homology theory USE Giẻ Triêng (Vietnamese people) K9 (Fictitious character) NT Whitehead groups Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) (May Subd Geog) K 37 (Military aircraft) K. Tzetnik Award in Holocaust Literature [DS528.2.K2] USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) UF Ka-Tzetnik Award UF Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) K 98 k (Rifle) Peras Ḳ. Tseṭniḳ BT Ethnology—Burma USE Mauser K98k rifle Peras Ḳatseṭniḳ ʾKa nao dialect (May Subd Geog) K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 BT Literary prizes—Israel BT China—Languages USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 K2 (Pakistan : Mountain) Hmong language K.A. Lind Honorary Award UF Dapsang (Pakistan) Ka nō (Burmese people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Godwin Austen, Mount (Pakistan) USE Tha noʹ (Burmese people) K.A. Linds hederspris Gogir Feng (Pakistan) Ka Rang (Southeast Asian people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Mount Godwin Austen (Pakistan) USE Sedang (Southeast Asian people) K-ABC (Intelligence test) BT Mountains—Pakistan Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children Karakoram Range USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine K-B Bridge (Palau) K2 (Drug) Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Synthetic marijuana Ka-taw K-BIT (Intelligence test) K3 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Takraw USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test USE Broad Peak (Pakistan and China) Ka Tawng Luang (Southeast Asian people) K. -

The Indo-Aryan Languages: a Tour of the Hindi Belt: Bhojpuri, Magahi, Maithili

1.2 East of the Hindi Belt The following languages are quite closely related: 24.956 ¯ Assamese (Assam) Topics in the Syntax of the Modern Indo-Aryan Languages February 7, 2003 ¯ Bengali (West Bengal, Tripura, Bangladesh) ¯ Or.iya (Orissa) ¯ Bishnupriya Manipuri This group of languages is also quite closely related to the ‘Bihari’ languages that are part 1 The Indo-Aryan Languages: a tour of the Hindi belt: Bhojpuri, Magahi, Maithili. ¯ sub-branch of the Indo-European family, spoken mainly in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldive Islands by at least 640 million people (according to the 1.3 Central Indo-Aryan 1981 census). (Masica (1991)). ¯ Eastern Punjabi ¯ Together with the Iranian languages to the west (Persian, Kurdish, Dari, Pashto, Baluchi, Ormuri etc.) , the Indo-Aryan languages form the Indo-Iranian subgroup of the Indo- ¯ ‘Rajasthani’: Marwar.i, Mewar.i, Har.auti, Malvi etc. European family. ¯ ¯ Most of the subcontinent can be looked at as a dialect continuum. There seem to be no Bhil Languages: Bhili, Garasia, Rathawi, Wagdi etc. major geographical barriers to the movement of people in the subcontinent. ¯ Gujarati, Saurashtra 1.1 The Hindi Belt The Bhil languages occupy an area that abuts ‘Rajasthani’, Gujarati, and Marathi. They have several properties in common with the surrounding languages. According to the Ethnologue, in 1999, there were 491 million people who reported Hindi Central Indo-Aryan is also where Modern Standard Hindi fits in. as their first language, and 58 million people who reported Urdu as their first language. Some central Indo-Aryan languages are spoken far from the subcontinent. -

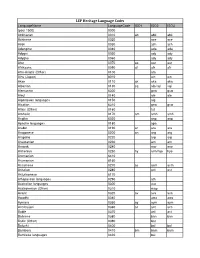

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama -

Revising the Bantu Tree

Cladistics Cladistics (2018) 1–20 10.1111/cla.12353 Revising the Bantu tree Peter M. Whiteleya, Ming Xuea and Ward C. Wheelerb,* aDivision of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central Park West, New York, NY, 10024-5192, USA; bDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central Park West, New York, NY, 10024-5192, USA Accepted 15 June 2018 Abstract Phylogenetic methods offer a promising advance for the historical study of language and cultural relationships. Applications to date, however, have been hampered by traditional approaches dependent on unfalsifiable authority statements: in this regard, historical linguistics remains in a similar position to evolutionary biology prior to the cladistic revolution. Influential phyloge- netic studies of Bantu languages over the last two decades, which provide the foundation for multiple analyses of Bantu socio- cultural histories, are a major case in point. Comparative analyses of basic lexica, instead of directly treating written words, use only numerical symbols that express non-replicable authority opinion about underlying relationships. Building on a previous study of Uto-Aztecan, here we analyse Bantu language relationships with methods deriving from DNA sequence optimization algorithms, treating basic vocabulary as sequences of sounds. This yields finer-grained results that indicate major revisions to the Bantu tree, and enables more robust inferences about the history of Bantu language expansion and/or migration throughout sub-Saharan Africa. “Early-split” versus “late-split” hypotheses for East and West Bantu are tested, and overall results are com- pared to trees based on numerical reductions of vocabulary data. Reconstruction of language histories is more empirically based and robust than with previous methods. -

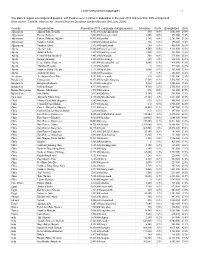

Data Source : Todd M. Johnson, Ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014)

Least evangelized megapeoples 1 The globe’s largest unevangelized peoples: 247 Peoples over 1 million in population in the year 2015 and less than 50% evangelized. Data source : Todd M. Johnson, ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014). Country People Name Population 2015 Language Autoglossonym Christians Chr% Evangelized Ev% Afghanistan Afghani Tajik (Tadzhik) 8,002,000 tajiki-afghanistan 800 0.0% 1,601,000 20.0% Afghanistan Hazara (Berberi) 2,604,000 hazaragi central 1,000 0.0% 574,000 22.0% Afghanistan Pathan (Pukhtun, Afghani) 11,995,000 pashto 2,400 0.0% 2,761,000 23.0% Afghanistan Southern Pathan 1,600,000 paktyan-pashto 320 0.0% 198,000 12.4% Afghanistan Southern Uzbek 2,590,000 özbek south 260 0.0% 466,000 18.0% Algeria Algerian Arab 23,684,000 jaza'iri general 9,500 0.0% 9,128,000 38.5% Algeria Arabized Berber 1,219,000 jaza'iri general 1,200 0.1% 544,000 44.6% Algeria Central Shilha (Beraber) 1,483,000 ta-mazight 300 0.0% 378,000 25.5% Algeria Hamyan Bedouin 2,836,000 hassaniyya 280 0.0% 582,000 20.5% Algeria Lesser Kabyle (Eastern) 1,002,000 tha-qabaylith east 5,000 0.5% 421,000 42.0% Algeria Shawiya (Chaouia) 2,129,000 shawiya 0 0.0% 479,000 22.5% Algeria Southern Shilha (Shleuh) 1,113,000 ta-shelhit 1,000 0.1% 363,000 32.6% Algeria Tajakant Bedouin 1,666,000 hassaniyya 0 0.0% 262,000 15.8% Azerbaijan Azerbaijani (Azeri Turk) 8,182,000 azeri north 820 0.0% 2,701,000 33.0% Bangladesh Chittagonian 13,475,000 bangla-chittagong 17,500 0.1% 5,542,000 41.1% Bangladesh Rangpuri (Rajbansi) 10,170,000 rajbangshi -

The Phonology and Morphology of Kisi

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title The Phonology and Morphology of Kisi Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7b3788dp Author Childs, George Publication Date 1988 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Phonology and Morphology of Kisi By George Tucker Childs A.B. (Stanford University) 1970 M.Ed. (University of Virginia) 1979 M.A. (University of California) 1982 C.Phil. (University of California) 1987 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Chairman Date r, DOCTORAL DEGREE CONFERRED MAT 20,1980 , Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE PHONOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGY OF KISI Copyright (£) 1988 All rights reserved. George Tucker Childs Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE PHONOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGY OF KISI George Tucker Childs ABSTRACT This dissertation describes the phonology and morphology of the Kisi language, a member of the Southern Branch of (West) Atlantic. The language is spoken in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. After the introduction in Chapter 1 and an overview of the language in Chapter 2, I discuss the phonology of the language. The phonemic inventory has implosives, a full series of nasal compound stops, and a set of labialvelars. The vowels form a symmetrical seven- vowel pattern, and length is contrastive. Syllable structure is , C(G)V(V)(C), where the only consonants allowed to close syllables are the liquid and two nasals. Kisi is a tonal language with the following tones: Low, High, Extra-High (limited distribution), Rise, and Fall. -

The Languages of South Asia

THE LANGUAGES OF SOUTH ASIA a catalogue of rare books: dictionaries, grammars, manuals, & literature. with several important works on Tibetan Catalogue 31 John Randall (Books of Asia) John Randall (Books of Asia) [email protected] +44 (0)20 7636 2216 www.booksofasia.com VAT Number : GB 245 9117 54 Cover illustration taken from no. 4 (Colebrooke) in this catalogue; inside cover illustrations taken from no. 206 (Williams). © John Randall (Books of Asia) 2017 THE LANGUAGES OF SOUTH ASIA Catalogue 31 John Randall (Books of Asia) INTRODUCTION The conversion of the East India Company from trading concern to regional power South Asia, home to six distinct linguistic gave further impetus to the study of South families, remains one of the most Asian languages. Employees of the linguistically complex regions on earth. Company were charged with producing According to the 2001 Census of India, linguistic guides for official purposes. 1,721 languages and dialects were spoken as Military officers needed language skills to mother tongues. Of these, 29 had one issue commands to locally recruited troops. million or more speakers, and a further 31 And as the Company sought to perpetuate more than 100,000. the Mughal system of rule, knowledge of Persian as well as regional languages was The political implications of such dizzying essential for revenue collectors and diversity have been no less complex. Since administrators of justice. 1953, there have been many attempts to re- divide the country along linguistic lines. As All the while, some independent European recently as 2014, the new state of Telangana scholars demonstrated a genuine interest in was created as a homeland for Telugu and empathy for South Asian languages and speakers. -

Paper Download

Culture survival for the indigenous communities with reference to North Bengal, Rajbanshi people and Koch Bihar under the British East India Company rule (1757-1857) Culture survival for the indigenous communities (With Special Reference to the Sub-Himalayan Folk People of North Bengal including the Rajbanshis) Ashok Das Gupta, Anthropology, University of North Bengal, India Short Abstract: This paper will focus on the aspect of culture survival of the local/indigenous/folk/marginalized peoples in this era of global market economy. Long Abstract: Common people are often considered as pre-state primitive groups believing only in self- reliance, autonomy, transnationality, migration and ancient trade routes. They seldom form their ancient urbanism, own civilization and Great Traditions. Or they may remain stable on their simple life with fulfillment of psychobiological needs. They are often considered as serious threat to the state instead and ignored by the mainstream. They also believe on identities, race and ethnicity, aboriginality, city state, nation state, microstate and republican confederacies. They could bear both hidden and open perspectives. They say that they are the aboriginals. States were in compromise with big trade houses to counter these outsiders, isolate them, condemn them, assimilate them and integrate them. Bringing them from pre-state to pro-state is actually a huge task and you have do deal with their production system, social system and mental construct as well. And till then these people love their ethnic identities and are in favour of their cultural survival that provide them a virtual safeguard and never allow them to forget about nature- human-supernature relationship: in one phrase the way of living. -

South Asian Languages Analysis SALA- 35 October 29-31, 2019

South Asian Languages Analysis SALA- 35 October 29-31, 2019 Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales 65, rue des Grands Moulins, Paris 13 Organizer: Ghanshyam Sharma Sceintific Committee: Anne Abeillé (University of Paris 7, France) Rajesh Bhatt (University of Massachussetts, USA) Tanmoy Bhattacharya (University of Delhi, India) Miriam Butt (University of Konstanz, Germany) Veneeta Dayal (Yale University, USA) Hans Henrich Hock (University of Illinois, USA) Peter Edwin Hook (University of Virginia, USA) Emily Manetta (University of Vermont, USA) Annie Montaut (INALCO, Paris, France) John Peterson (University of Kiel, Germany) Pollet Samvelian (University of Paris 3, France) Anju Saxena (University of Uppsala, Sweden) Ghanshyam Sharma (INALCO, Paris, France) Collaborators: François Auffret Francesca Bombelli Petra Kovarikova Vidisha Prakash 2 Table of Contents INVITED TALKS .................................................................................................................................... 13 [1] Implications of Feature Realization in Hindi‐Urdu: the case of Copular Sentences ― Rajesh Bha, University of Massachusetts, Amherst (joint work with Sakshi Bhatia, IIT Delhi) ............................ 13 [2] Word Order Effects and Parcles in Urdu Quesons ― Miriam Bu, Konstanz University, Germany 13 [3] The Multiple Faces of Hindi‐Urdu bhii ― Veneeta Dayal, Yale University, USA ............................... 13 [4] Kashmiri and the verb‐stranding verb‐phrase ellipsis debate ― Emily Manea, University of Vermont,