Data Source : Todd M. Johnson, Ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Arabic Sociolinguistics: Topics in Diglossia, Gender, Identity, And

Arabic Sociolinguistics Arabic Sociolinguistics Reem Bassiouney Edinburgh University Press © Reem Bassiouney, 2009 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in ll/13pt Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and East bourne A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 2373 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 2374 7 (paperback) The right ofReem Bassiouney to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements viii List of charts, maps and tables x List of abbreviations xii Conventions used in this book xiv Introduction 1 1. Diglossia and dialect groups in the Arab world 9 1.1 Diglossia 10 1.1.1 Anoverviewofthestudyofdiglossia 10 1.1.2 Theories that explain diglossia in terms oflevels 14 1.1.3 The idea ofEducated Spoken Arabic 16 1.2 Dialects/varieties in the Arab world 18 1.2. 1 The concept ofprestige as different from that ofstandard 18 1.2.2 Groups ofdialects in the Arab world 19 1.3 Conclusion 26 2. Code-switching 28 2.1 Introduction 29 2.2 Problem of terminology: code-switching and code-mixing 30 2.3 Code-switching and diglossia 31 2.4 The study of constraints on code-switching in relation to the Arab world 31 2.4. 1 Structural constraints on classic code-switching 31 2.4.2 Structural constraints on diglossic switching 42 2.5 Motivations for code-switching 59 2. -

Analogy in Lovari Morphology

Analogy in Lovari Morphology Márton András Baló Ph.D. dissertation Supervisor: László Kálmán C.Sc. Doctoral School of Linguistics Gábor Tolcsvai Nagy MHAS Theoretical Linguistics Doctoral Programme Zoltán Bánréti C.Sc. Department of Theoretical Linguistics Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest Budapest, 2016 Contents 1. General introduction 4 1.1. The aim of the study of language . 4 2. Analogy in grammar 4 2.1. Patterns and exemplars versus rules and categories . 4 2.2. Analogy and similarity . 6 2.3. Neither synchronic, nor diachronic . 9 2.4. Variation and frequency . 10 2.5. Rich memory and exemplars . 12 2.6. Paradigms . 14 2.7. Patterns, prototypes and modelling . 15 3. Introduction to the Romani language 18 3.1. Discovery, early history and research . 18 3.2. Later history . 21 3.3. Para-Romani . 22 3.4. Recent research . 23 3.5. Dialects . 23 3.6. The Romani people in Hungary . 28 3.7. Dialects in Hungary . 29 3.8. Dialect diversity and dialectal pluralism . 31 3.9. Current research activities . 33 3.10. Research of Romani in Hungary . 34 3.11. The current research . 35 4. The Lovari sound system 37 4.1. Consonants . 37 4.2. Vowels . 37 4.3. Stress . 38 5. A critical description of Lovari morphology 38 5.1. Nominal inflection . 38 5.1.1. Gender . 39 5.1.2. Animacy . 40 5.1.3. Case . 42 5.1.4. Additional features. 47 5.2. Verbal inflection . 50 5.2.1. The present tense . 50 5.2.2. Verb derivation. 54 5.2.2.1. Transitive derivational markers . -

De Sousa Sinitic MSEA

THE FAR SOUTHERN SINITIC LANGUAGES AS PART OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA (DRAFT: for MPI MSEA workshop. 21st November 2012 version.) Hilário de Sousa ERC project SINOTYPE — École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected]; [email protected] Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be periphery. In the core are Mon-Khmer languages like Vietnamese and Khmer, and Kra-Dai languages like Lao and Thai. The core languages generally have: – Lexical tonal and/or phonational contrasts (except that most Khmer dialects lost their phonational contrasts; languages which are primarily tonal often have five or more tonemes); – Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words; – Strong left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order. The Sino-Tibetan languages, like Burmese and Mandarin, are said to be periphery to the MSEA linguistic area. The periphery languages have fewer traits that are typical to MSEA. For instance, Burmese is SOV and right-headed in general, but it has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘stative verbs’) and numerals. Mandarin is SVO and has prepositions, but it is otherwise strongly right-headed. These two languages also have fewer lexical tones. This paper aims at discussing some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and comparing them with the MSEA typological canon. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language area, the Far Southern Sinitic languages, namely Yuè, Pínghuà, the Sinitic dialects of Hǎinán and Léizhōu, and perhaps also Hakka in Guǎngdōng (largely corresponding to Chappell (2012, in press)’s ‘Southern Zone’) are less ‘fringe’ than the other Sinitic languages from the point of view of the MSEA linguistic area. -

Alfaz E Mewat's RJ Team Comprises A

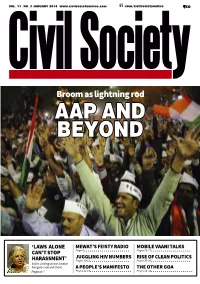

VOL. 11 NO. 3 JANUARY 2014 www.civilsocietyonline.com .com/civilsocietyonline `50 broom as lightning rod AAAAAAPPP AAAnnnddd bbbeeeyyyooonnnddd ‘Laws aLone mewat’s feisty radio mobiLe Vaani taLks can’t stop Page 9 Pages 26-27 juggLing hiV numbers rise of cLean poLitics harassment’ Pages 10-11 Pages 29-30 Indira Jaising on the Justice Ganguly case and more a peopLe’s manifesto the other goa Pages 6-7 Pages 12-13 Pages 33-34 CONTENTs READ U S. WE READ YO U. the new politics s a magazine we have been keenly interested in efforts to clean up politics and improve governance. Our first issue, in september A2003, was on RTI and it had the then unknown Arvind Kejriwal on the cover. Our second issue, in October 2003, was about sheila Dikshit and how she was using RWAs to reach out to the middle class. Our third cover story, in November 2003, was titled ‘NGOs in Politics’ – it was about activists trying to influence politics and impact election outcomes. When we recall those issues, now 10 years old, we coVer story can’t help patting ourselves on the back. We had caught a trend much before anyone else had. The civil society aap and beyond space had begun taking shape in India and it was clear that important beginnings were being made in trans - The Aam Aadmi Party’s spectacular performance in Delhi heralds forming politics. Aruna Roy, Medha Patkar and a whole changing trends in Indian politics. Is this a movement or a party? lot of others were not only speaking for the weak and Is it a quick fix or a long-term solution? 20 powerless, but also trying to change the agendas of political parties. -

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies Organized by With support from from PRIMUS Visual Histories of South Asia Foreword by Christopher Pinney Edited by Annamaria Motrescu-Mayes and Marcus Banks This book wishes to introduce the scholars of South Asian and Indian History to the in-depth evaluation of visual research methods as the research framework for new historical studies. This volume identifies and evaluates the current developments in visual sociology and digital anthropology, relevant to the study of contemporary South Asian constructions of personal and national identities. This is a unique and excellent contribution to the field of South Asian visual studies, art history and cultural analysis. This text takes an interdisciplinary approach while keeping its focus on the visual, on material cultural and on art and aesthetics. – Professor Kamran Asdar Ali, University of Texas at Austin 978-93-86552-44-0 u Royal 8vo u 312 pp. u 2018 u HB u ` 1495 u $ 71.95 u £ 55 Hidden Histories Religion and Reform in South Asia Edited by Syed Akbar Hyder and Manu Bhagavan Dedicated to Gail Minault, a pioneering scholar of women’s history, Islamic Reformation and Urdu Literature, Hidden Histories raises questions on the role of identity in politics and private life, memory and historical archives. Timely and thought provoking, this book will be of interest to all who wish to study how the diverse and plural past have informed our present. Hidden Histories powerfully defines and celebrates a field that has refused to be occluded by majoritarian currents. – Professor Kamala Visweswaran, University of California, San Diego 978-93-86552-84-6 u Royal 8vo u 324 pp. -

A Case Study of the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple and Its Lantern Festival Celebration

religions Article The Hainanese Temples of Singapore: A Case Study of the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple and Its Lantern Festival Celebration Yiwen Ji Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, Singapore 119260, Singapore; [email protected] Received: 25 May 2020; Accepted: 8 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Shui Wei Sheng Niang (4>#娘) Temple is located within a united temple at 109a, Hougang Avenue 5, Singapore. Shui Wei Sheng Niang is a Hainanese goddess. the worship of whom is widespread in Hainanese communities in South East Asia. This paper examines a specific Hainanese temple and how its rituals reflect the history of Hainanese immigration to Singapore. The birthday rites of the goddess (Lantern Festival Celebration) are held on the 4th and 14th of the first lunar month. This paper also introduces the life history and ritual practices of a Hainanese Daoist master and a Hainanese theater actress. Keywords: Singapore; Hainanese temples; Shuiwei Shengniang; Daoist masters; opera singers 1. Introduction Although the original Hainan village of Hougang no longer exists in Singapore due to the urbanization and renovation of Singapore, people of that Hainanese community still gather together to celebrate the Lantern Festival and worship the goddess Shui Wei Sheng Niang (4>#娘), who originated from Hainan Island. This shows how Hainanese descendants still have the autonomy to maintain their cultural, religious, and dialect-based identity. The traditional Keepers of the Incense Burners and Village Heads of Ritual are still selected each New Year before celebrations begin. This indicates that the customary institutions of decision-making within the Hainanese community are still alive. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona. -

The Forms of Seeking Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language

THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 T.U. Reg. No.:9-2-540-164-2010 Date of Approval Thesis Fourth Semester Examination Proposal: 18/12/2017 Exam Roll No.: 28710094/072 Date of Submission: 30/05/2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that to the best of my knowledge this thesis is original; no part of it was earlier submitted for the candidate of research degree to any university. Date: ..…………………… Jyoti Kaushal i RECOMMENDATION FOR ACCEPTANCE This is to certify that Miss Jyoti Kaushal has prepared this thesis entitled The Forms of Seeking, Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language under my guidance and supervision I recommend this thesis for acceptance Date: ………………………… Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav Reader Department of English Education Faculty of Education TU, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal ii APPROVAL FOR THE RESEARCH This thesis has been recommended for evaluation from the following Research Guidance Committee: Signature Dr. Prem Phyak _______________ Lecturer & Head Chairperson Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav (Supervisor) _______________ Reader Member Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. -

Genealogical Classification of New Indo-Aryan Languages and Lexicostatistics

Anton I. Kogan Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Russia, Moscow); [email protected] Genealogical classification of New Indo-Aryan languages and lexicostatistics Genetic relations among Indo-Aryan languages are still unclear. Existing classifications are often intuitive and do not rest upon rigorous criteria. In the present article an attempt is made to create a classification of New Indo-Aryan languages, based on up-to-date lexicosta- tistical data. The comparative analysis of the resulting genealogical tree and traditional clas- sifications allows the author to draw conclusions about the most probable genealogy of the Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords: Indo-Aryan languages, language classification, lexicostatistics, glottochronology. The Indo-Aryan group is one of the few groups of Indo-European languages, if not the only one, for which no classification based on rigorous genetic criteria has been suggested thus far. The cause of such a situation is neither lack of data, nor even the low level of its historical in- terpretation, but rather the existence of certain prejudices which are widespread among In- dologists. One of them is the belief that real genetic relations between the Indo-Aryan lan- guages cannot be clarified because these languages form a dialect continuum. Such an argu- ment can hardly seem convincing to a comparative linguist, since dialect continuum is by no means a unique phenomenon: it is characteristic of many regions, including those where Indo- European languages are spoken, e.g. the Slavic and Romance-speaking areas. Since genealogi- cal classifications of Slavic and Romance languages do exist, there is no reason to believe that the taxonomy of Indo-Aryan languages cannot be established. -

Chen Hawii 0085A 10047.Pdf

PROTO-ONG-BE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 2018 By Yen-ling Chen Dissertation Committee: Lyle Campbell, Chairperson Weera Ostapirat Rory Turnbull Bradley McDonnell Shana Brown Keywords: Ong-Be, Reconstruction, Lingao, Hainan, Kra-Dai Copyright © 2018 by Yen-ling Chen ii 知之為知之,不知為不知,是知也。 “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” iii Acknowlegements First of all, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Lyle Campbell, the chair of my dissertation and the historical linguist and typologist in my department for his substantive comments. I am always amazed by his ability to ask mind-stimulating questions, and I thank him for allowing me to be part of the Endangered Languages Catalogue (ELCat) team. I feel thankful to Dr. Shana Brown for bringing historical studies on minorities in China to my attention, and for her support as the university representative on my committee. Special thanks go to Dr. Rory Turnbull for his constructive comments and for encouraging a diversity of point of views in his class, and to Dr. Bradley McDonnell for his helpful suggestions. I sincerely thank Dr. Weera Ostapirat for his time and patience in dealing with me and responding to all my questions, and for pointing me to the directions that I should be looking at. My reconstruction would not be as readable as it is today without his insightful feedback. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Alexis Michaud.