E-Learning and Wellbeing of Those in Poverty in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

CHAPTER-V · Linguistic Question : a Cultural Resurgence CHAPTER-V LINGUISTIC QUESTION: a CULTURAL RESURGENCE

CHAPTER-V · Linguistic Question : A Cultural Resurgence CHAPTER-V LINGUISTIC QUESTION: A CULTURAL RESURGENCE. Language is one of the major issues of socio-cultural aspect of a community. The language/ dialect of Northeastern part of India is genetically of the eastern group of the Indo- Aryan family (along with~ at least Oriy_a, B.angla and Assamiy~) with in the member of th~ Putative Bengali- Assames sub- group .1 There is a general view among the scholars that this language/ dialect is spoken in East Purnea district of Bihar, Morang and Jhapa districts of Nepal; Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, Darjeeling and Dinajpur ,Maida· districts of West Bengal ; the old Goalpara district of Assam (now Dhubri, Bongaigaon, Kokrajhar, Goalpara); Rangpur, Dinajpur and Mymensingh district of Bangladesh.2 The spoken language of the Rajbanshi people has been identified in various way such as northern dialect of Bengali, 3 Goalparia dialect of Assamese, 4 Kamta, 5 Kamrupi, 6 Deshi, 7 Kamtai language, 8 Kamta Behari9 etc. Sir George A. Grierson in his Linguistic Survey of India has first mentioned the ·language used by the Rajbanshis of Rangpur, Darjeeling, . 10 . Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri, and Goalpara as a separate dialect. He named this dialect as 'Rajbanshi' since this is spoken mostly by the Rajbanshis but he considered it a dialect of Bengali itself. 11 Rajbanshi dialect accordiQg to Grierson "belong to.. the eastern variety of th~ language, has still points of different, which entitle it to be classes as a separate dialect. It has one sub- dialect called 'Bahe' spoken in the Darjeeling Teari." 12 Grierson also argued that the Koches who adopted Hinduism and Islam generally speak the Rajbanshi dialect and it is called the 'Rangpuri'. -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 A’ou [aou] Iouo China 2 Abai Sungai [abf] Iouo Malaysia 3 Abaza [abq] Iouo Russia, Turkey 4 Abinomn [bsa] Iouo Indonesia 5 Abkhaz [abk] Iouo Georgia, Turkey 6 Abui [abz] Iouo Indonesia 7 Abun [kgr] Iouo Indonesia 8 Aceh [ace] Iouo Indonesia 9 Achang [acn] Iouo China, Myanmar 10 Ache [yif] Iouo China 11 Adabe [adb] Iouo East Timor 12 Adang [adn] Iouo Indonesia 13 Adasen [tiu] Iouo Philippines 14 Adi [adi] Iouo India 15 Adi, Galo [adl] Iouo India 16 Adonara [adr] Iouo Indonesia Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Russia, Syria, 17 Adyghe [ady] Iouo Turkey 18 Aer [aeq] Iouo Pakistan 19 Agariya [agi] Iouo India 20 Aghu [ahh] Iouo Indonesia 21 Aghul [agx] Iouo Russia 22 Agta, Alabat Island [dul] Iouo Philippines 23 Agta, Casiguran Dumagat [dgc] Iouo Philippines 24 Agta, Central Cagayan [agt] Iouo Philippines 25 Agta, Dupaninan [duo] Iouo Philippines 26 Agta, Isarog [agk] Iouo Philippines 27 Agta, Mt. Iraya [atl] Iouo Philippines 28 Agta, Mt. Iriga [agz] Iouo Philippines 29 Agta, Pahanan [apf] Iouo Philippines 30 Agta, Umiray Dumaget [due] Iouo Philippines 31 Agutaynen [agn] Iouo Philippines 32 Aheu [thm] Iouo Laos, Thailand 33 Ahirani [ahr] Iouo India 34 Ahom [aho] Iouo India 35 Ai-Cham [aih] Iouo China 36 Aimaq [aiq] Iouo Afghanistan, Iran 37 Aimol [aim] Iouo India 38 Ainu [aib] Iouo China 39 Ainu [ain] Iouo Japan 40 Airoran [air] Iouo Indonesia 1 Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 41 Aiton [aio] Iouo India 42 Akeu [aeu] Iouo China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang -

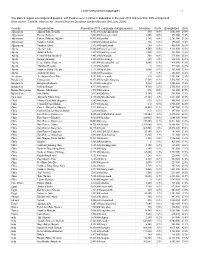

Data Source : Todd M. Johnson, Ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014)

Least evangelized megapeoples 1 The globe’s largest unevangelized peoples: 247 Peoples over 1 million in population in the year 2015 and less than 50% evangelized. Data source : Todd M. Johnson, ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014). Country People Name Population 2015 Language Autoglossonym Christians Chr% Evangelized Ev% Afghanistan Afghani Tajik (Tadzhik) 8,002,000 tajiki-afghanistan 800 0.0% 1,601,000 20.0% Afghanistan Hazara (Berberi) 2,604,000 hazaragi central 1,000 0.0% 574,000 22.0% Afghanistan Pathan (Pukhtun, Afghani) 11,995,000 pashto 2,400 0.0% 2,761,000 23.0% Afghanistan Southern Pathan 1,600,000 paktyan-pashto 320 0.0% 198,000 12.4% Afghanistan Southern Uzbek 2,590,000 özbek south 260 0.0% 466,000 18.0% Algeria Algerian Arab 23,684,000 jaza'iri general 9,500 0.0% 9,128,000 38.5% Algeria Arabized Berber 1,219,000 jaza'iri general 1,200 0.1% 544,000 44.6% Algeria Central Shilha (Beraber) 1,483,000 ta-mazight 300 0.0% 378,000 25.5% Algeria Hamyan Bedouin 2,836,000 hassaniyya 280 0.0% 582,000 20.5% Algeria Lesser Kabyle (Eastern) 1,002,000 tha-qabaylith east 5,000 0.5% 421,000 42.0% Algeria Shawiya (Chaouia) 2,129,000 shawiya 0 0.0% 479,000 22.5% Algeria Southern Shilha (Shleuh) 1,113,000 ta-shelhit 1,000 0.1% 363,000 32.6% Algeria Tajakant Bedouin 1,666,000 hassaniyya 0 0.0% 262,000 15.8% Azerbaijan Azerbaijani (Azeri Turk) 8,182,000 azeri north 820 0.0% 2,701,000 33.0% Bangladesh Chittagonian 13,475,000 bangla-chittagong 17,500 0.1% 5,542,000 41.1% Bangladesh Rangpuri (Rajbansi) 10,170,000 rajbangshi -

ONLINE APPENDIX: Not for Print Publication

ONLINE APPENDIX: not for print publication A Additional Tables and Figures Figure A1: Permutation Tests Panel A: Female Labor Force Participation Panel B: Gender Difference in Labor Force Participation A1 Table A1: Cross-Country Regressions of LFP Ratio Dependent variable: LFPratio Specification: OLS OLS OLS (1) (2) (3) Proportion speaking gender language -0.16 -0.25 -0.18 (0.03) (0.04) (0.04) [p < 0:001] [p < 0:001] [p < 0:001] Continent Fixed Effects No Yes Yes Country-Level Geography Controls No No Yes Observations 178 178 178 R2 0.13 0.37 0.44 Robust standard errors are clustered by the most widely spoken language in all specifications; they are reported in parentheses. P-values are reported in square brackets. LFPratio is the ratio of the percentage of women in the labor force, mea- sured in 2011, to the percentage of men in the labor force. Geography controls are the percentage of land area in the tropics or subtropics, average yearly precipitation, average temperature, an indicator for being landlocked, and the Alesina et al. (2013) measure of suitability for the plough. A2 Table A2: Cross-Country Regressions of LFP | Including \Bad" Controls Dependent variable: LFPf LFPf - LFPm Specification: OLS OLS (1) (2) Proportion speaking gender language -6.66 -10.42 (2.80) (2.84) [p < 0:001] [p < 0:001] Continent Fixed Effects Yes Yes Country-Level Geography Controls Yes Yes Observations 176 176 R2 0.57 0.68 Robust standard errors are clustered by the most widely spoken language in all specifications; they are reported in parentheses. -

Paper Download

Culture survival for the indigenous communities with reference to North Bengal, Rajbanshi people and Koch Bihar under the British East India Company rule (1757-1857) Culture survival for the indigenous communities (With Special Reference to the Sub-Himalayan Folk People of North Bengal including the Rajbanshis) Ashok Das Gupta, Anthropology, University of North Bengal, India Short Abstract: This paper will focus on the aspect of culture survival of the local/indigenous/folk/marginalized peoples in this era of global market economy. Long Abstract: Common people are often considered as pre-state primitive groups believing only in self- reliance, autonomy, transnationality, migration and ancient trade routes. They seldom form their ancient urbanism, own civilization and Great Traditions. Or they may remain stable on their simple life with fulfillment of psychobiological needs. They are often considered as serious threat to the state instead and ignored by the mainstream. They also believe on identities, race and ethnicity, aboriginality, city state, nation state, microstate and republican confederacies. They could bear both hidden and open perspectives. They say that they are the aboriginals. States were in compromise with big trade houses to counter these outsiders, isolate them, condemn them, assimilate them and integrate them. Bringing them from pre-state to pro-state is actually a huge task and you have do deal with their production system, social system and mental construct as well. And till then these people love their ethnic identities and are in favour of their cultural survival that provide them a virtual safeguard and never allow them to forget about nature- human-supernature relationship: in one phrase the way of living. -

Childbreaking Yards Child Labour in the Ship Recycling Industry in Bangladesh

In cooperation with the International Platform on Shipbreaking CHILDBREAKING YARDS Child Labour in the Ship Recycling Industry in Bangladesh Article I: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article II: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status (…) Arti- cle III: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article IV: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article V: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or Introduction 05 Hazardous work, deadly yards Child labour in Bangladesh Objective and methodology Causes of child labour at shipbreaking yards 08 Loss of land Disappearance of the father Indebtedness Current practices 15 Profile of the children Hiring process Type of work Working conditions Duration of work and salary Training and Protection Risks, pains and insults Disease and Accidents Living Conditions Portraits 23 Ibrahim Sohel Mitu Abul Kasem © Ruben Dao © Ruben Legal framework and government response 27 International legal framework on shipbreaking Basel convention ILO IMO EU International Legal Framework relating to working conditions and children’s rights ILO Conventions CRC ICESCR Domestic legal framework: Labour Act 2006 Government response Conclusions/Recommendations 32 Acknowledgements The field research carried out in March and April 2008 could not have been possible without the support of numerous local people who helped us access the shipbreaking yards, a place where NGOs are typically not welcome. -

The Grammatical Variation Between Standard B

Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN 2347-5374(Online) Abbreviated Key Title: Sch. J. Arts Humanit. Soc. Sci. ISSN 2347-9493(Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publishers (SAS Publishers) A Unit of Scholars Academic and Scientific Society, India The Grammatical Variation between Standard Bangla and Mymensingh Dialect Mohammed Jasim Uddin Khan1*, Iftakhar Ahmed2 1Lecturer (English), Prime University Mirpur 1, Dhaka 1216, Bangladesh 2Lecturer (English), Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University, Tangail, Dhaka, Bangladesh Abstract: Bangla is an Eastern Indo-Aryan language which belongs to Indo-European *Corresponding author language family. Bangla is the national language of Bangladesh. Regional variation in Mohammed Jasim Uddin spoken Bangla is a very common phenomenon. The native speaker of Mymensingh Khan practice Bangla in their everyday communication and Mymensingh dialect has a clear discrepancy from Standard Bangla with regard to grammar. This study explores the Article History extent of variations of Mymensingh dialect from Standard Bangla in terms of Received: 16.05.2018 grammar. To collect data, the researcher visited the different areas of the target area. Accepted: 26.05.2018 The respondents were different kinds of people such as ward leaders, religious leaders, Published: 30.05.2018 farmers, teachers, housewives etc. The language of print and electronic media has been considered as Standard Bangla. DOI: Keywords: Standard Bangla, Mymensingh dialect, grammatical variation. 10.21276/sjahss.2018.6.5.18 INTRODUCTION Bangla is the official language of Bangladesh. It is an Eastern Indo-Aryan language. Bangla has several dialects and Mymensingh dialect is one of them. Mymensingh district is situated in the north area of Bangladesh. -

BUP JOURNAL Editorial Board

BUP JOURNAL Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Major General Abul Kalam Md Humayun Kabir, ndu, psc Vice Chancellor, BUP Editor Colonel Md. Nazrul Islam, psc Inspector of Colleges, BUP Members Dr. Atiqur Rahman Adjunct Professor, John Cabot University Prof. Dr. Khandoker Mokkadem Hossain Rome, Italy Institute of Disaster Managment & Vulnerability Studies, University of Dhaka Prof. Dr. Nazmul Ahsan Kalimullah Department of Public Administration Prof. Dr. Delwar Hossain University of Dhaka Department of International Relations Faculty of Social Sciences Dr. Md. Abdur Rauf University of Dhaka Department of Civil Engineering Bangladesh University of Engineering and Kabir M Ashraf Alam Technology, Dhaka Director General, National Institute of Local Government (NILG) Prof. Dr. M Kaykobad Institute of Information & Communication Brigadier General Technology, Bangladesh University of Syed Mofazzel Mawla (Retd) Engineering and Technology, Dhaka Controller of Examinations, BUP Dr. Nazrul Islam Brigadier General Dean, Faculty of Business Administration Shah Atiqur Rahman, ndc, psc Eastern University, Dhaka Registrar, BUP Prof. Dr. Kamal Uddin Ahmed Group Captain SMG Yeazdani Chairman, Department of English psc, PhD European University of Bangladesh, Dhaka Dean and Professor, Faculty of General Studies, BUP Assistant Editors: A T M Mozaffor Hossain Dr. Mohammad Lutfur Rahman Assistant Inspector of Colleges Assistant Professor BUP Faculty of Technical & Engineering Studies BUP Editorial Policy The BUP JOURNAL is published once in a year. The BUP JOURNAL is of a multidimensional nature and welcomes research based scholarly articles on - but not restricted to - development, security, education, science, technology, engineering, good governance, environment and disaster management, socio-economics, medical science and other fields related to the development of Bangladesh.