A Case Study of the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple and Its Lantern Festival Celebration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Sousa Sinitic MSEA

THE FAR SOUTHERN SINITIC LANGUAGES AS PART OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA (DRAFT: for MPI MSEA workshop. 21st November 2012 version.) Hilário de Sousa ERC project SINOTYPE — École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected]; [email protected] Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be periphery. In the core are Mon-Khmer languages like Vietnamese and Khmer, and Kra-Dai languages like Lao and Thai. The core languages generally have: – Lexical tonal and/or phonational contrasts (except that most Khmer dialects lost their phonational contrasts; languages which are primarily tonal often have five or more tonemes); – Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words; – Strong left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order. The Sino-Tibetan languages, like Burmese and Mandarin, are said to be periphery to the MSEA linguistic area. The periphery languages have fewer traits that are typical to MSEA. For instance, Burmese is SOV and right-headed in general, but it has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘stative verbs’) and numerals. Mandarin is SVO and has prepositions, but it is otherwise strongly right-headed. These two languages also have fewer lexical tones. This paper aims at discussing some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and comparing them with the MSEA typological canon. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language area, the Far Southern Sinitic languages, namely Yuè, Pínghuà, the Sinitic dialects of Hǎinán and Léizhōu, and perhaps also Hakka in Guǎngdōng (largely corresponding to Chappell (2012, in press)’s ‘Southern Zone’) are less ‘fringe’ than the other Sinitic languages from the point of view of the MSEA linguistic area. -

Chen Hawii 0085A 10047.Pdf

PROTO-ONG-BE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 2018 By Yen-ling Chen Dissertation Committee: Lyle Campbell, Chairperson Weera Ostapirat Rory Turnbull Bradley McDonnell Shana Brown Keywords: Ong-Be, Reconstruction, Lingao, Hainan, Kra-Dai Copyright © 2018 by Yen-ling Chen ii 知之為知之,不知為不知,是知也。 “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” iii Acknowlegements First of all, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Lyle Campbell, the chair of my dissertation and the historical linguist and typologist in my department for his substantive comments. I am always amazed by his ability to ask mind-stimulating questions, and I thank him for allowing me to be part of the Endangered Languages Catalogue (ELCat) team. I feel thankful to Dr. Shana Brown for bringing historical studies on minorities in China to my attention, and for her support as the university representative on my committee. Special thanks go to Dr. Rory Turnbull for his constructive comments and for encouraging a diversity of point of views in his class, and to Dr. Bradley McDonnell for his helpful suggestions. I sincerely thank Dr. Weera Ostapirat for his time and patience in dealing with me and responding to all my questions, and for pointing me to the directions that I should be looking at. My reconstruction would not be as readable as it is today without his insightful feedback. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Alexis Michaud. -

Synchrony and Diachrony of Sinitic Languages: a Brief History of Chinese Dialects

I Synchrony and Diachrony of Sinitic Languages: A Brief History of Chinese Dialects HILARY CHAPPELL l.l Introduction Even though Sinitic languages are spoken by more than one billion people, very little research has been carried out on the synchronic grammar of major languages and dialect groups of Chinese, apart from standard Mandarin or plttdnghuA *Effi, and Cantonese to a lesser extent. The same situation applies to the diachrony of Sinitic languages with respect to the exact relationship between Archaic and Medieval Chinese and contemporary dialects. Since diachronic and historical research reveals important insights into earlier stages of grammar and morphology, it cannot but form a crucial link with syn- chronic studies. First, it can be expected that different kinds of archaic and medieval features are potentially preserved in certain of the more conservative dialect groups of Sinitic. Second, clues to the pathways of grammaticalization and semantic change can only be clearly delineated with reference to precise analyses of earlier stages of the Chinese language. These are two decisive factors in employ- ing both approaches to syntactic research in the one analysis. Indeed, the main motivation behind compiling this volume of studies on the grammar of Sinitic languages (or Chinese dialects) is to highlight the work of linguists who use the two intertwined perspectives of synchrony and diachrony in their research. A corollary of this first view, espoused in this anthology either explicitly or implicitly is that if only standard Mandarin grammar is analysed, then such con- nections between the diachronic and the synchronic state may often be over- looked. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & Unreached People Groups of Northern Asia AGWM Ed. Source: Joshua Project Da

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups of Northern Asia AGWM ed. Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net I give credit & thanks to Asia Harvest for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer & Devotional Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs of Northern Asia SUMMARY: 544 total People Groups; (+Hong Kong & Macau) 443 JP Least Reached = LR-UPG = shaded; Downloaded & updated from www.joshuaproject.net in August, 2020 LR-UPG: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." * * * Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! * * * Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. 28:19-20! * People without Jesus are eternally lost, & Jesus is the only One who can save them, John 14:6! * We have been given "the ministry & message of reconciliation", in Christ, 2 Cor. -

The Changing Chinese Linguistic Situation in Suriname Under New Migration

CHAPTER 9 They Might as Well Be Speaking Chinese: The Changing Chinese Linguistic Situation in Suriname under New Migration Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat 1 Introduction This chapter presents one of the most obvious local examples, to the Surinamese public at least, of the link between mobility, language, and iden- tity: current Chinese migration. These ‘New Chinese’ migrants since the 1990s were linguistically quite different from the established Hakkas in Suriname, and were the cause of an upsurge in anti-Chinese sentiments. It will be argued that the aforementioned link is constructed in the Surinamese imagination in the context of ethnic and civic discourse to reproduce the image of a mono- lithic, undifferentiated, Chinese migrant group, despite increasing variety and change within the Chinese segment of Surinamese society. The point will also be made that the Chinese stereotype affects the way demographic and linguis- tic data relating to Chinese are produced by government institutions. We will present a historic overview of the Chinese presence in Suriname, a brief eth- nographic description of Chinese migrant cohorts, followed by some data on written Chinese in Suriname. Finally we present the available data on Chinese ethnicity and language from the Surinamese General Bureau of Statistics (abs). An ethnic Chinese segment has existed in Surinamese society since the middle of the nineteenth century, as a consequence of Dutch colonial policy to import Asian indentured labour as a substitute for African slave labour. Indentured labourers from Hakka villages in the Fuitungon Region (particu- larly Dongguan and Baoan)1 in the second half of the nineteenth century made way for entrepreneurial chain migrants up to the first half of the twentieth 1 The established Hakka migrants in Suriname refer to the area as fui5tung1on1 (惠東安), which is an anagram of the Kejia pronunciation of the names of the three counties where the ‘Old Chinese’ migrant cohorts in Suriname come from: fui5jong2 (惠陽 Putonghua: huìyáng), tung1kon1 (東莞 pth: dōngguǎn), and pau3on1 (寳安 pth: bǎoān). -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Han Chinese, Hainanese April 9

Han Chinese, Hainanese April 9 GUANGDONG bones. Associated with ancestor worship and •Lingao divination are the Shang HAINAN ISLAND Dan Xian • bronze vessels, the surfaces •Changcheng •Baisha of which are covered with •Tongshi extraordinarily detailed linear •Ledong designs.”2 The Shang Dynasty Scale 0KM80 was overthrown around 1100 Population in China: BC. Chinese have lived on 4,400,000 (1987) Hainan Island since Madame 5,143,600 (2000) Xian — a leader of the Yue 5,812,300 (2010) minority tribes of southern Location: Hainan Island Religion: No Religion China — pledged allegiance Christians: 92,000 to the Sui Dynasty rulers in 3 the sixth century AD. Overview of the Hainanese Customs: Most Hainanese earn their livelihood from Countries: China, Vietnam, Laos fishing or agriculture. Severe Pronunciation: “Hi-nahn” and sudden storms lash the Other Names: Chinese: Qiongwen, Qiongwen, Hainan Chinese Hainan coastline every Population Source: summer, causing massive 4,400,000 (1987 LAC); damage to homes and boats. Out of a total Han population of New industry and factories 1,042,482,187 (1990 census); Also in Vietnam and Laos have sprung up on Hainan in Location: NE Hainan Island and the last decade. Significant along the coastline of most of Paul Hattaway numbers of Hainanese are the island except the northwest Location: Five million Hainanese Chinese employed by the expanding tourist industry Status: Officially included under are concentrated in the northeastern parts which has catered to a growing number of Han Chinese of China’s Hainan (South Sea) Island. They Chinese and foreign tourists since the early Language: Chinese, Qiongwen are located along the coast in a clockwise 1980s. -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2019-062 (completed by Registration authority) Date: 2019 Aug 31 Primary Person submitting request: Kirk Miller E-mail address: kirkmiller at gmail dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests Type of change proposed (check one): 1. Modify reference information for an existing language code element 2. Propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group 3. Retire a language code element from use (duplicate or non-existent) 4. Expand the denotation of a code element through the merging one or more language code elements into it (retiring the latter group of code elements) 5. Split a language code element into two or more new code elements 6. Create a code element for a previously unidentified language For proposing a change to an existing code element, please identify: Affected ISO 639-3 identifier: nan Associated reference name: Min Nan Chinese 5. Split a language code element into two or more code elements (a) List the languages into which this code element should be split: Hokkien / Hoklo / Quanzhang Chinese Chaoshan Min / Teo-Swa Chinese Datian Min Chinese Leizhou Min Chinese Hainanese Min / Qiong Wen Chinese (b) Referring to the criteria given above, give the rationale for splitting the existing code element into two or more languages: The varieties of Min Nan are not mutually intelligible. -

The Far Southern Sinitic Languages As Part of Mainland Southeast Asia

Hilário de Sousa The far southern Sinitic languages as part of Mainland Southeast Asia 1 Introduction Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011, Comrie 2007), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be in the periphery. In the core are the Mon-Khmer and Kra-Dai languages. The core languages generally have: Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words Strong syntactic left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order Phonemic tonal contrasts and/or phonational contrasts The Chamic languages (Austronesian) and the Hmong-Mien languages are also in the region, and are typologically relatively similar to the Mon- Khmer and Kra-Dai languages. On the other hand, there are the Sino-Tibetan languages in the northern and western periphery; their linguistic properties are somewhat less MSEA-like. For instance, in contrast to the strong syntactic left-headedness that is typical of MSEA languages, Burmese is OV and right- headed in general.1 On the other hand, Mandarin has the left-headed traits of VO word order and preposition. However, Mandarin is otherwise strongly right-headed (e.g. right-headed noun phrases, adjunct-verb order). These two languages also have fewer lexical tones than most tonal languages in MSEA. The aim of this paper is to discuss some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and to compare them with the typological profiles of some MSEA languages. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language 1 Nonetheless, Burmese still has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘sta- tive verbs’) and numerals. -

Proto-Ong-Be (PDF)

PROTO-ONG-BE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 2018 By Yen-ling Chen Dissertation Committee: Lyle Campbell, Chairperson Weera Ostapirat Rory Turnbull Bradley McDonnell Shana Brown Keywords: Ong-Be, Reconstruction, Lingao, Hainan, Kra-Dai Copyright © 2018 by Yen-ling Chen ii 知之為知之,不知為不知,是知也。 “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” iii Acknowlegements First of all, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Lyle Campbell, the chair of my dissertation and the historical linguist and typologist in my department for his substantive comments. I am always amazed by his ability to ask mind-stimulating questions, and I thank him for allowing me to be part of the Endangered Languages Catalogue (ELCat) team. I feel thankful to Dr. Shana Brown for bringing historical studies on minorities in China to my attention, and for her support as the university representative on my committee. Special thanks go to Dr. Rory Turnbull for his constructive comments and for encouraging a diversity of point of views in his class, and to Dr. Bradley McDonnell for his helpful suggestions. I sincerely thank Dr. Weera Ostapirat for his time and patience in dealing with me and responding to all my questions, and for pointing me to the directions that I should be looking at. My reconstruction would not be as readable as it is today without his insightful feedback. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Alexis Michaud. -

The Sanjiangren in Singapore © 2012 Shen Lingxie

Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 5, 2011-12 南方華裔研究雜志, 第五卷, 2011-12 The Sanjiangren in Singapore © 2012 Shen Lingxie* Introduction The Chinese population in Singapore is a migrant community, a part of the large-scale Chinese diaspora in the region set in motion by Western colonialism at the turn of the twentieth century. As with other overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, the large majority of these migrants were from southern China; the Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese constitute three-quarters of the Chinese population in Singapore today.1 Most studies of the Chinese society in Singapore have hence focused on these dialect groups and to a lesser extent the Hakka and the Hainanese as well. Minority dialect groups such as the Sanjiangren, are in comparison almost negligible in number, and have largely been overlooked in historical writings though Liu Hong and Wong Sin Kiong have described the existence of a “Sanjiang” community in Singapore in their work Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, and Cheng Lim-Keak mentioned the “Sanjiangren” as a community that specialised in furniture and dress-making in Social Change and the Chinese in Singapore. The Shaw brothers Tan Sri Runme (邵仁枚) and Sir Run Run (邵逸夫), famed film producers and cinema owners are Sanjiangren.2 So are Chiang Yick Ching, founder of his eponymous CYC Shanghai Shirts Company that dressed Singapore’s Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew, and Chou Sing Chu (周星衢) who started the bookstore chain Popular. 3 Singaporeans are well acquainted with these enterprises, but few are aware of which dialect group their founders belong to. -

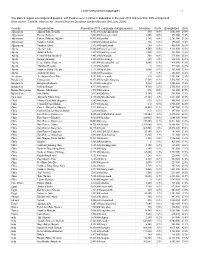

Data Source : Todd M. Johnson, Ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014)

Least evangelized megapeoples 1 The globe’s largest unevangelized peoples: 247 Peoples over 1 million in population in the year 2015 and less than 50% evangelized. Data source : Todd M. Johnson, ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014). Country People Name Population 2015 Language Autoglossonym Christians Chr% Evangelized Ev% Afghanistan Afghani Tajik (Tadzhik) 8,002,000 tajiki-afghanistan 800 0.0% 1,601,000 20.0% Afghanistan Hazara (Berberi) 2,604,000 hazaragi central 1,000 0.0% 574,000 22.0% Afghanistan Pathan (Pukhtun, Afghani) 11,995,000 pashto 2,400 0.0% 2,761,000 23.0% Afghanistan Southern Pathan 1,600,000 paktyan-pashto 320 0.0% 198,000 12.4% Afghanistan Southern Uzbek 2,590,000 özbek south 260 0.0% 466,000 18.0% Algeria Algerian Arab 23,684,000 jaza'iri general 9,500 0.0% 9,128,000 38.5% Algeria Arabized Berber 1,219,000 jaza'iri general 1,200 0.1% 544,000 44.6% Algeria Central Shilha (Beraber) 1,483,000 ta-mazight 300 0.0% 378,000 25.5% Algeria Hamyan Bedouin 2,836,000 hassaniyya 280 0.0% 582,000 20.5% Algeria Lesser Kabyle (Eastern) 1,002,000 tha-qabaylith east 5,000 0.5% 421,000 42.0% Algeria Shawiya (Chaouia) 2,129,000 shawiya 0 0.0% 479,000 22.5% Algeria Southern Shilha (Shleuh) 1,113,000 ta-shelhit 1,000 0.1% 363,000 32.6% Algeria Tajakant Bedouin 1,666,000 hassaniyya 0 0.0% 262,000 15.8% Azerbaijan Azerbaijani (Azeri Turk) 8,182,000 azeri north 820 0.0% 2,701,000 33.0% Bangladesh Chittagonian 13,475,000 bangla-chittagong 17,500 0.1% 5,542,000 41.1% Bangladesh Rangpuri (Rajbansi) 10,170,000 rajbangshi