THE FIJIAN LANGUAGE the FIJIAN LANGU AGE the FIJIAN LANGUAGE Albert J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alignment Mouth Demonstrations in Sign Languages Donna Jo Napoli

Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstrations in sign languages Donna Jo Napoli, Swarthmore College, [email protected] Corresponding Author Ronice Quadros, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, [email protected] Christian Rathmann, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, [email protected] 1 Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstrations in sign languages Abstract: Non-manual articulations in sign languages range from being semantically impoverished to semantically rich, and from being independent of manual articulations to coordinated with them. But, while this range has been well noted, certain non-manuals remain understudied. Of particular interest to us are non-manual articulations coordinated with manual articulations, which, when considered in conjunction with those manual articulations, are semantically rich. In which ways can such different articulators coordinate and what is the linguistic effect or purpose of such coordination? Of the non-manual articulators, the mouth is articulatorily the most versatile. We therefore examined mouth articulations in a single narrative told in the sign languages of America, Brazil, and Germany. We observed optional articulations of the corners of the lips that align with manual articulations spatially and temporally in classifier constructions. The lips, thus, enhance the message by giving redundant information, which should be particularly useful in narratives for children. Examination of a single children’s narrative told in these same three sign languages plus six other sign languages yielded examples of one type of these optional alignment articulations, confirming our expectations. Our findings are coherent with linguistic findings regarding phonological enhancement and overspecification. Keywords: sign languages, non-manual articulation, mouth articulation, hand-mouth coordination 2 Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstration articulations in sign languages 1. -

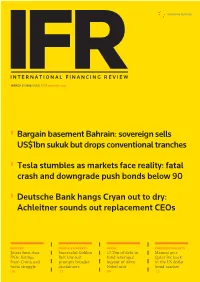

Sovereign Sells US$1Bn Sukuk but Drops Conventional Tranches

MARCH 31 2018 ISSUE 2227 www.ifre.com Bargain basement Bahrain: sovereign sells US$1bn sukuk but drops conventional tranches Tesla stumbles as markets face reality: fatal crash and downgrade push bonds below 90 Deutsche Bank hangs Cryan out to dry: Achleitner sounds out replacement CEOs EQUITIES PEOPLE & MARKETS LOANS EMERGING MARKETS Jitters hurt Asia Successful Golden €7.3bn of debt to Mannai gets IPOs: listings Belt law suit fund leveraged Qatar Inc back from China and prompts broader buyout of Akzo in the US dollar India struggle disclaimers Nobel unit bond market 06 07 09 12 SAVE THE DATE: MAY 22 2018 GREEN FINANCING ROUNDTABLE TUESDAY MAY 22 2018 | THOMSON REUTERS BUILDING, CANARY WHARF, LONDON Sponsored by: Green bond issuance broke through the US$150bn mark in 2017, a 78% increase over the total recorded in 2016, and there are hopes that it will double again this year. But is it on track to reach the US$1trn mark targeted by Christina Figueres? This timely Roundtable will bring together a panel of senior market participants to assess the current state of the market, examine the challenges and opportunities and provide an outlook for the rest of the year and beyond. This free-to-attend event takes place in London on the morning of Tuesday May 22 2018. If you would like to be notified as soon as registration is live, please email [email protected]. Upfront OPINION INTERNATIONAL FINANCING REVIEW Dead man walking? Rocket man t was another terrible week for Deutsche Bank. But this ast November, an analyst at Germany’s Nord/LB said it Itime it wasn’t John Cryan’s fault. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. Language in a Fijian Village An Ethnolinguistic Study Annette Schmidt A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. September 1988 ABSTRACT This thesis investigates sociolinguistic variation in the Fijian village of Waitabu. The aim is to investigate how particular uses, functions and varieties of language relate to social patterns and modes of interaction. ·The investigation focuses on the various ways of speaking which characterise the Waitabu repertoire, and attempts to explicate basic sociolinguistic principles and norms for contextually appropriate behaviour.The general purpose is to explicate what the outsider needs to know to communicate appropriately in Waitabu community. Chapter one discusses relevant literature and the theoretical perspective of the thesis. I also detail the fieldwork setting, problems and restrictions, and thesis plan. Chapter two provides the necessary background information to this study, describing the geographical, demographical and sociohistorical setting. Description is given of the contemporary language situation, structure of Fijian (Bouma dialect), and Waitabu social structure and organisation. In Chapter 3, the kinship system which lies at the heart of Waitabu social organisation, and kin-based sociolinguistic roles are analysed. This chapter gives detailed description of the kin categories and the established modes of sociolinguistic behaviour which are associated with various kin-based social identities. -

Proceedings of the Pacific Regional Workshop on Mangrove Wetlands Protection and Sustainable Use

PROCEEDINGS OF THE PACIFIC REGIONAL WORKSHOP ON MANGROVE WETLANDS PROTECTION AND SUSTAINABLE USE THE UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC MARINE STUDIES FACILITY, SUVA, FIJI JUNE 12 – 16, 2001 Hosted by SOUTH PACIFIC REGIONAL ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME Funded by CANADA-SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM (C-SPODP II) ORGANISING COMMITTEE South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) Ms Mary Power Ms Helen Ng Lam Institute of Applied Sciences Ms Batiri Thaman Professor William Aalbersberg Editing: Professor William Aalbersberg, Batiri Thaman, Lilian Sauni Compiling: Batiri Thaman, Lilian Sauni ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The organisers of the workshop would like to thank the following people and organisations that contributed to the organising and running of the workshop. § Canada –South Pacific Ocean Deveopment Program (C-SPODP II) for funding the work- shop § South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) for organising the workshop § Institute of Applied Science (IAS) staff for the local organisation of the workshop and use of facilities § The local, regional, and international participants that presented country papers and technical reports § University of the Pacific (USP) dining hall for the catering § USP media centre for assistance with media equipment § Professor Randy Thaman for organising the field trip TABLE OF CONTENTS Organising Committee Acknowledgements Table of Contents Objectives and Expected Outcomes of Workshop Summary Report Technical Reports SESSION I: THE VALUE OF MANGROVE ECOSYSTEMS · The Value of Mangrove Ecosystems: -

Gun Law History in the United States and Second Amendment Rights

SPITZER_PROOF (DO NOT DELETE) 4/28/2017 12:07 PM GUN LAW HISTORY IN THE UNITED STATES AND SECOND AMENDMENT RIGHTS ROBERT J. SPITZER* I INTRODUCTION In its important and controversial 2008 decision on the meaning of the Second Amendment, District of Columbia v. Heller,1 the Supreme Court ruled that average citizens have a constitutional right to possess handguns for personal self- protection in the home.2 Yet in establishing this right, the Court also made clear that the right was by no means unlimited, and that it was subject to an array of legal restrictions, including: “prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.”3 The Court also said that certain types of especially powerful weapons might be subject to regulation,4 along with allowing laws regarding the safe storage of firearms.5 Further, the Court referred repeatedly to gun laws that had existed earlier in American history as a justification for allowing similar contemporary laws,6 even though the court, by its own admission, did not undertake its own “exhaustive historical analysis” of past laws.7 In so ruling, the Court brought to the fore and attached legal import to the history of gun laws. This development, when added to the desire to know our own history better, underscores the value of the study of gun laws in America. In recent years, new and important research and writing has chipped away at old Copyright © 2017 by Robert J. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

Grammar of Urdu Or Hindustani.Pdf

OF THE URDU OR HINDUSTANI LANGUAGE. BY THE SAME AUTHOR. Crown 8vo, cloth, price 2s. 6d. HINDUSTANI EXERCISES. A Series of Passages and Extracts adapted for Translation into Hindustani. Crown 8vo, cloth, price 7s. IKHWANU-9 SAFA, OR BROTHERS OF PURITY. Translated from the Hindustani. "It has been the translator's object to adhere as closely as possible to the original text while rendering the English smooth and intelligible to the reader, and in this design he has been throughout successful." Saturday Review. GRAMMAR URDU OR HINDUSTANI LANGUAGE. JOHN DOWSON, M.R.A.S., LAT5 PROCESSOR OF HINDCSTANI, STAFF COLLEGE. Cfjtrfl (SBitton. LONDON : KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO. L DRYDEN HOUSE, GERRARD STREET, W. 1908. [All riijhts reserved.] Printed by BALLANTYNK, HANSOM &* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh TABLE OF CONTENTS. PACK PREFACE . ix THE ALPHABET 1 Pronunciation . .5,217 Alphabetical Notation or Abjad . 1 7 Exercise in Reading . 18 THE AKTICLE 20 THE Nora- 20 Gender 21 Declension. ...... 24 Izafat 31 THE ADJECTIVE 32 Declension ...... 32 Comparison ... 33 PRONOUNS Personal. ...... 37 Demonstrative ...... 39 Respectful 40 Reflexive 41 Possessive 41 Relative and Correlative . .42 Interrogative . 42 Indefinite ....... 42 Partitive . 43 Compound. .43 VERB 45 Substantive and Auxiliary 46 Formation of . 46 Conjugation of Neuter Verbs . .49 Active Verbs . 54 Irregulars . .57 Hona 58 Additional Tenses . 60 2004670 CONTENTS. VERB (continued) Passive Verb ....... 62 Formation of Actives and Causals ... 65 Nominals 69 Intensives ..... 70 Potentials Completives . .72 Continuatives .... Desideratives ..... 73 Frequentatives .... 74 Inceptives . 75 Permissives Acquisitives . .76 Reiteratives ..... 76 ADVKRBS ......... 77 PREPOSITIONS 83 CONJUNCTIONS 90 INTERJECTIONS ....... 91 NUMERALS ......... 91 Cardinal 92 Ordinal 96 Aggregate 97 Fractional 97 Ralcam 98 Arabic 99 Persian 100 DERIVATION 101 Nouns of Agency . -

Why Washingtonâ•Žs Deadly Weapon Criminal Sentencing Enhancement

COMMENTS Dead Wrong: Why Washington’s Deadly Weapon Criminal Sentencing Enhancement Needs “Enhancement” James Harlan Corning* “Let it be said that I am right rather than consistent.”1 – Justice John Marshall Harlan I. INTRODUCTION The early 1990s saw a sharp increase in gun violence directed to- ward Washington’s law enforcement community.2 In the summer of 1994, the Puget Sound region was stunned by three separate, unrelated acts of violence against police officers and their families. On June 4th of that year, Seattle Police Detective Antonio Terry was gunned down on * J.D. Candidate, Seattle University School of Law, 2012; B.A., Social Sciences, University of Washington. I am profoundly grateful to Professor Laurel Oates, who inspired this Comment through a fascinating legal-writing assignment in my first semester of law school and who has con- stantly encouraged, mentored, and advised me during my law school journey. I am deeply indebted to the staff of the Seattle University Law Review for their support; in particular, I thank Mike Costel- lo, Joan Miller, Jacob Stender, Kyle Trethewey, and many others for giving so much time and effort to this piece. Lastly, I thank my incredible family and friends—and especially my wonderful fiancé, Eric Wolf—for their unwavering love, support, encouragement, and patience in all things. 1. Quoted in TINSLEY E. YARBROUGH, JUDICIAL ENIGMA: THE FIRST JUSTICE HARLAN 77 (1995). 2. Ignacio Lobos, Deputy’s Death Another Reminder of Dangers of Law Enforcement Jobs, SEATTLE TIMES, Aug. 17, 1994, http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=1994 0817&slug=1925831. -

Traditional & Modern Golic Vulcan

TRADITIONAL & MODERN GOLIC VULCAN - FEDERATION STANDARD ENGLISH DICTIONARY (компиляция от Агентства Переводов WordHouse) ABBREVIATIONS (anc.) from an ancient source which may or may not be in the Golic linguistic family (IGV) used only in Insular Golic Vulcan (but occasionally as a synonym in TGV & MGV) (LGV) used only in Lowlands Golic Vulcan (but occasionally as a synonym in TGV & MGV) (MGV) used only in Modern Golic Vulcan (NGS) a non-Golic word used by at least some Golic speakers (obs.) considered obsolete to most speakers of Golic Vulcan, but still might be used in ceremonies, literature, etc. (TGV) used only in Traditional Golic Vulcan All other abbreviations are standard dictionary abbreviations. A A'gal \ ɑ - ' gɑl \ -- proton (SST) A'gal-lushun -- proton torpedo Abru-spis -- anticline A'ho -- hello Abru-su'us -- numerator A'rak-, A'rakik \ ɑ - ' rɑk \ -- positive (polarity) Abru-tchakat -- camber (eng., mech.) A'rak-falun -- positive charge Abru-tus -- overload (n.) A'rak-falun-krus -- positive ion Abru-tus-nelayek -- overload suppressor A'rak-narak'es -- positive polarity Abru-tus-tor -- overload (v.) Aberala \ ɑ - be - ' rɑ - lɑ \ -- aerofoil, airfoil Abru-tvi-kovtra -- asthenosphere Aberala-tchakat \ - tʃɑ - ' kɑt \ -- camber (aero.) Abru-vulu -- obtuse angle Aberayek \ ɑ - be - ' rɑ - jek \ -- crane (n.) Abru-yetural-, Abru-yeturalik -- overdriven (adj.) Aberofek \ ɑ - be - ' ro - fek \ -- derrick Abru-zan-mev -- periscope Abevipladau -- dub (v.) Abrukhau -- dominate Abi' \ ɑ - ' bi \ -- until (prep.) Abrumashen-, abrumashenik -

Tolo Dictionary

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - No. 91 TOLO DICTIONARY by Susan Smith Crowley Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Crowley, S.S. Tolo dictionary. C-91, xiv + 129 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1986. DOI:10.15144/PL-C91.cover ©1986 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A - Occasional Papers SERIES B - Monographs SERIES C - Books SERIES D - Special Publications EDITOR: S.A. Wurm ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. W. Bender K.A. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics David Bradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii A. Capell P. MUhlhausler University of Sydney Linacre College, Oxford Michael G. Clyne G.N. O'Grady Monash University University of Victoria, B.C. S.H. Elbert A.K. Pawley University of Hawaii University of Auckland K.J. Franklin K.L. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics U ni versity of Texas G.W. Grace Malcolm Ross University of Hawaii Australian National University M.A.K. Halliday Gillian Sankoff University of Sydney University of Pennsylvania E. Haugen W.A.L. Stokhof Harvard University University of Leiden A. Healey B.K. T'sou Summer Institute of Linguistics City Polytechnic of Hong Kong L.A. -

Smaller Foraminifera from Eniwetok Drill Holes

Smaller Foraminifera From Eniwetok Drill Holes BIKINI AND NEARBY ATOLLS, MARSHALL ISLANDS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 260-X Smaller Foraminifera From Eniwetok Drill Holes By RUTH TODD and DORIS LOW BIKINI AND NEARBY ATOLLS, MARSHALL ISLANDS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 260-X Smaller Foraminifera were studied as loose specimens from 2 deep holes^ about 22 miles apart^ drilled to the basement rock underlying Eniwetok Atoll UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Systematic descriptions—Continued Page Abstract. ______________________________________ 799 Family Nonionidae_ ____________________________ 828 Introduction _-_------_--_-____________.________ 799 Family Camerinidae_ ____________.____-_-------- 829 Analysis of the faunas. __________________________ 800 Family Peneroplidae____________________________ 829 Correlation between Eniwetok and BikinL _____ 801 Family Heterohelicidae____-__-_-___-___-__--__-- 831 Drillhole E-l_. ____-___-_______--------____ 802 Family Buliminidae_-_--____-_-__-___---__-_____ 831 Drill hole F-l____----_____--___-_--__---___ 805 Family Spirillinidae-____________________________ 835 Comparison of conclusions based on smaller and Family Discorbidae. ____________________________ 836 larger Foraminifera _______________________ 807 Family Rotaliidae. ____-._-___-_--__-__---_--___ -

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE. The Court strongly prefers to use live interpreters in the courtrooms whenever possible. However, when the Court can’t find live interpreters, we sometimes use Language Line, a national telephone service supplying interpreters for most languages on the planet almost immediately. The number for that service is 1-800-874-9426. Contact Circuit Administration at 605-367-5920 for the Court’s account number and authorization codes. AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE/DEAF INTERPRETATION Minnehaha County in the 2nd Judicial Circuit uses a combination of local, highly credentialed ASL/Deaf interpretation providers including Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD), Interpreter Services Inc. (ISI), and highly qualified freelancers for the courts in Sioux Falls, Minnehaha County, and Canton, Lincoln County. We are also happy to make court video units available to any other courts to access these interpreters from Sioux Falls (although many providers have their own video units now). The State of South Dakota has also adopted certification requirements for ASL/deaf interpretation “in a legal setting” in 2006. The following link published by the State Department of Human Services/ Division of Rehabilitative Services lists all the certified interpreters in South Dakota and their certification levels, and provides a lot of other information on deaf interpretation requirements and services in South Dakota. DHS Deaf Services AFRICAN DIALECTS A number of the residents of the 2nd Judicial Circuit speak relatively obscure African dialects. For court staff, attorneys, and the public, this list may be of some assistance in confirming the spelling and country of origin of some of those rare African dialects.