2017 Saikia Smitana 1218624

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Word-Order in Boro Language

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Word-Order in Boro Language Dr. Kanun Basumatary Guest Lecturer, North Eastern Regional Language Centre Guwahati-29, Assam, India Abstract: The present study attempts to analysis and to discuss about the word-order of the Boro language. The Boro language is originated from the Tibeto-Burman group of Sino-Tibetan language family. The language is mainly spoken in Assam and its adjacent areas or countries of India. Like Nepal, Meghalaya, Bangladesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, West Bengal etc. The Boro language has some special features in terms of using word-order pattern and it found in different types. The Boro language is found in SOV word-order pattern mainly and along with this pattern there are different types of word- orders in that language. The Tibeto-Burman languages are found in verb-final position. The Boro language is same in such feature. Keywords : Word-order, Boro, Language, SOV, OSV 1. Introduction Boro is the name of the community as well as the language. The Boro language belongs to Sino- Tibetan language family. This stock originated in the plain areas of Yang-Tsze-Kiang and Huang-ho rivers in China. Now, this language family is well spread throughout the eastern and south-eastern parts of Asia including Burma and North eastern parts of India including Assam (MR Baro, 2007:1). The Boro language originated from the Tibeto-Burman sub family of Sino-Tibetan language family. Its well spread throughout the Assam specially in the northern parts of Assam and its adjacent areas. -

Votes, Voters and Voter Lists: the Electoral Rolls in Barak Valley, Assam

SHABNAM SURITA | 83 Votes, Voters and Voter Lists: The Electoral Rolls in Barak Valley, Assam Shabnam Surita Abstract: Electoral rolls, or voter lists, as they are popularly called, are an integral part of the democratic setup of the Indian state. Along with their role in the electoral process, these lists have surfaced in the politics of Assam time and again. Especially since the 1970s, claims of non-citizens becoming enlisted voters, incorrect voter lists and the phenomenon of a ‘clean’ voter list have dominated electoral politics in Assam. The institutional acknowledgement of these issues culminated in the Assam Accord of 1985, establishing the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), a political party founded with the goal of ‘cleaning up’ the electoral rolls ‘polluted with foreign nationals’. Moreo- ver, the Assam Agitation, between 1979 and 1985, changed the public discourse on the validity of electoral rolls and turned the rolls into a major focus of political con- testation; this resulted in new terms of citizenship being set. However, following this shift, a prolonged era of politicisation of these rolls continued which has lasted to this day. Recently, discussions around the electoral rolls have come to popular and academic attention in light of the updating of the National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship Amendment Act. With the updating of the Register, the goal was to achieve a fair register of voters (or citizens) without outsiders. On the other hand, the Act seeks to modify the notion of Indian citizenship with respect to specific reli- gious identities, thereby legitimising exclusion. As of now, both the processes remain on functionally unclear and stagnant grounds, but the process of using electoral rolls as a tool for both electoral gain and the organised exclusion of a section of the pop- ulation continues to haunt popular perceptions. -

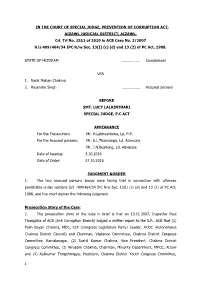

1 in the COURT of SPECIAL JUDGE, PREVENTION of CORRUPTION ACT, AIZAWL JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AIZAWL. Crl. Trl No. 1511 of 2010 in AC

IN THE COURT OF SPECIAL JUDGE, PREVENTION OF CORRUPTION ACT, AIZAWL JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AIZAWL. Crl. Trl No. 1511 of 2010 in ACB Case No. 2/2007 U/s 409/464/34 IPC R/w Sec. 13(I) (c) (d) and 13 (2) of PC Act, 1988. STATE OF MIZORAM ……………… Complainant VRS 1. Rasik Mohan Chakma 2. Rosendro Singh ……………… Accused persons BEFORE SMT. LUCY LALRINTHARI SPECIAL JUDGE, P.C ACT APPEARANCE For the Prosecution: Mr. H.Lalmuankima, Ld. P.P. For the Accused persons: Mr. S.L.Thansanga, Ld. Advocate Mr. J.N.Bualteng, Ld. Advocate Date of hearing: 3.10.2016 Date of Order: 27.10.2016 JUDGMENT &ORDER 1. The two accused persons above were facing trial in connection with offences punishable under sections U/s 409/464/34 IPC R/w Sec. 13(I) (c) (d) and 13 (2) of PC Act, 1988, and the court deliver the following judgment. Prosecution Story of the Case: 2. The prosecution story of the case in brief is that on 13.11.2007, Inspector Paul Thangzika of ACB (Anti Corruption Branch) lodged a written report to the S.P., ACB that (1) Pulin Bayan Chakma, MDC, CLP (Congress Legislature Party) Leader, ACDC (Autonomous Chakma District Council) and Chairman, Vigilance Committee, Chakma District Congress Committee, Kamalanagar, (2) Sushil Kumar Chakma, Vice President, Chakma District Congress Committee, (3) Nirupam Chakma, Chairman, Minority Department, MPCC, Aizawl and (4) Kalikumar Tongchongya, President, Chakma District Youth Congress Committee, 1 Kamalanagar had submitted a written complaint to His Excellency, the Governor of Mizoram against the authority of Chama Autonomous District Council for dishonestly mis-utilizing the Centrally sponsored Scheme (CSS) under the scheme of Rashtriya Sam Vikash Yojana (RSVY). -

List of Organisations/Individuals Who Sent Representations to the Commission

1. A.J.K.K.S. Polytechnic, Thoomanaick-empalayam, Erode LIST OF ORGANISATIONS/INDIVIDUALS WHO SENT REPRESENTATIONS TO THE COMMISSION A. ORGANISATIONS (Alphabetical Order) L 2. Aazadi Bachao Andolan, Rajkot 3. Abhiyan – Rural Development Society, Samastipur, Bihar 4. Adarsh Chetna Samiti, Patna 5. Adhivakta Parishad, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh 6. Adhivakta Sangh, Aligarh, U.P. 7. Adhunik Manav Jan Chetna Path Darshak, New Delhi 8. Adibasi Mahasabha, Midnapore 9. Adi-Dravidar Peravai, Tamil Nadu 10. Adirampattinam Rural Development Association, Thanjavur 11. Adivasi Gowari Samaj Sangatak Committee Maharashtra, Nagpur 12. Ajay Memorial Charitable Trust, Bhopal 13. Akanksha Jankalyan Parishad, Navi Mumbai 14. Akhand Bharat Sabha (Hind), Lucknow 15. Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, New Delhi 16. Akhil Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, New Delhi 17. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 18. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Mirzapur 19. Akhil Bharatiya Bhil Samaj, Ratlam District, Madhya Pradesh 20. Akhil Bharatiya Bhrastachar Unmulan Avam Samaj Sewak Sangh, Unna, Himachal Pradesh 21. Akhil Bharatiya Dhan Utpadak Kisan Mazdoor Nagrik Bachao Samiti, Godia, Maharashtra 22. Akhil Bharatiya Gwal Sewa Sansthan, Allahabad. 23. Akhil Bharatiya Kayasth Mahasabha, Amroh, U.P. 24. Akhil Bharatiya Ladhi Lohana Sindhi Panchayat, Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh 25. Akhil Bharatiya Meena Sangh, Jaipur 26. Akhil Bharatiya Pracharya Mahasabha, Baghpat,U.P. 27. Akhil Bharatiya Prajapati (Kumbhkar) Sangh, New Delhi 28. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtrawadi Hindu Manch, Patna 29. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Brahmin Mahasangh, Unnao 30. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Congress Alap Sankyak Prakosht, Lakheri, Rajasthan 31. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan 32. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Mumbai 33. -

CONFERENCE REPORT the 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE of the NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS SOCIETY 12-14 February 2010, Shillong, Meghalaya, India

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 33.1 — April 2010 CONFERENCE REPORT THE 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS SOCIETY 12-14 February 2010, Shillong, Meghalaya, India Stephen Morey La Trobe University The 5th conference of the North East Indian Linguistics Society (NEILS) was held from 12th to 14th February 2010 at the Don Bosco Institute (DBI), Kharguli Hills, Guwahati, Assam. The conference was preceded by a two day workshop, hosted by Gauhati University,1 but also held at DBI. NEILS is grateful to the Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, for providing funds to assist in the running of the workshops and conference. The two day workshop was in two parts: one day on using the Toolbox program, run by Virginia and David Phillips of SIL; and one day on working with tones, presented by Mark W. Post, Stephen Morey and Priyankoo Sarmah. Both workshops were well-attended and participatory in nature. The tones workshop included an intensive session of the Boro language, with five native speakers, all students of the Gauhati University Linguistics Department, providing information on their language and interacting with the participants. The conference itself began on 12th February with the launch of Morey and Post (2010) North East Indian Linguistics, Volume 2, performed by Nayan J. Kakoty, Resident Area Manager of Cambridge University Press India. This volume contains peer-reviewed and edited papers from the 2nd NEILS conference, held in 2007, representing NEILS’ commitment to the publication of the conference papers. A notable feature of the conference was the presence of seven people, from India, Burma, Australia and Germany, working on the Tangsa group of languages spoken on the India-Burma border. -

An Experimental Analysis of Speech Features for Tone Speech Recognition

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-9 Issue-2, December 2019 An Experimental Analysis of Speech Features for Tone Speech Recognition Utpal Bhattacharjee, Jyoti Mannala Abstract: Recently Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) has broad categories - characteristics tone and significance been successfully integrated in many commercial applications. tone. Characteristic tone is the method of grouping of musical These applications are performing significantly well in relatively pitch which characterize a particular language, language controlled acoustical environments. However, the performance of group or language family. Significant tone on the other hand an Automatic Speech Recognition system developed for non-tonal languages degrades considerably when tested for tonal languages. plays an active part in the grammatical significance of the One of the main reason for this performance degradation is the language, may be a means of distinguishing words of non-consideration of tone related information in the feature set of different meaning otherwise phonetically alike. A generally the ASR systems developed for non-tonal languages. In this paper accepted definition of tone language was proposed by K.Pink we have investigated the performance of commonly used feature [5]. According to this definition, a tone language must have for tonal speech recognition. A model has been proposed for lexical constructive tone. In generative phonology, it means extracting features for tonal speech recognition. A statistical analysis has been done to evaluate the performance of proposed tone of a tonal phonemes are no way predictable, must have feature set with reference to the Apatani language of Arunachal to specify in the lexicon of each morpheme [3]. -

20 December 2002

MON ASH UNIVERSITY THESIS ACCEPTED IN SATISFACTION OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ON. n . 20 December 2002 Research Graduate Sc'nool Committee Under the copyright Act 1968, this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing for the purposes of research, criticism or review. In particular no results or conclusions should be extracted from it, nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. ERRATA p 255 para 2, 3rd line. "Furthermore" for "Furthemore" p 257 para 2, 3rd line: "the Aitons" for "The Aitons" th p xiii para 5,4 line: "compiled" for "complied" p 269 para 1, 1* line: omit "see" nd p xvii para 1, 2 line: "other" for "othr" p 293 para 1, 3rd line: "not" for "nor" rd p xix para 8, 3 line: omit *ull stop after "the late" p 301 para 1, 4th line: "post-modify" for "post-modifier" rd p 5 para 5, 3 line: "bandh is often" for "bandh often" p 306 example (64), 6th line, "3PI" for "3Sg" th p 21 para 1, 4 line: "led" for "lead" p 324 footnote 61, 2nd line: "whether (76) is a case" for "whether (76) a nd p 29 footnote 21, 2 line: omit one "that" case" st p 34 para 2,1 line: substitute a comma for the full stop p 333 para 1, 3rd line: "as is" for "as does" st p 67 para 3,1 line: "contains" for "contain" p 334 para 1, last line: add final full stop p 71 last para, last line: "the" for "The" p 334 para 2, 1st line: "Example" for "Examples" -

The Naga Language Groups Within the Tibeto-Burman Language Family

TheNaga Language Groups within the Tibeto-Burman Language Family George van Driem The Nagas speak languages of the Tibeto-Burman fami Ethnically, many Tibeto-Burman tribes of the northeast ly. Yet, according to our present state of knowledge, the have been called Naga in the past or have been labelled as >Naga languages< do not constitute a single genetic sub >Naga< in scholarly literature who are no longer usually group within Tibeto-Burman. What defines the Nagas best covered by the modern more restricted sense of the term is perhaps just the label Naga, which was once applied in today. Linguistically, even today's >Naga languages< do discriminately by Indo-Aryan colonists to all scantily clad not represent a single coherent branch of the family, but tribes speaking Tibeto-Burman languages in the northeast constitute several distinct branches of Tibeto-Burman. of the Subcontinent. At any rate, the name Naga, ultimately This essay aims (1) to give an idea of the linguistic position derived from Sanskrit nagna >naked<, originated as a titu of these languages within the family to which they belong, lar label, because the term denoted a sect of Shaivite sadhus (2) to provide a relatively comprehensive list of names and whose most salient trait to the eyes of the lay observer was localities as a directory for consultation by scholars and in that they went through life unclad. The Tibeto-Burman terested laymen who wish to make their way through the tribes labelled N aga in the northeast, though scantily clad, jungle of names and alternative appellations that confront were of course not Hindu at all. -

1.How Many People Died in the Earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal? A

www.sarkariresults.io 1.How many people died in the earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal? A. 40,000 B. 100,000 C. 50,000 D. 500,000 2. When was Congress of Vienna opened? A. 1814 B. 1817 C. 1805 D. 1810 3. Which country was defeated in the Napoleonic Wars? A. Germany B. Italy C. Belgium D. France 4. When was the Vaccine for diphtheria founded? A. 1928 B. 1840 C. 1894 D. 1968 5. When did scientists detect evidence of light from the universe’s first stars? A. 2012 B. 2017 C. 1896 D. 1926 6. India will export excess ___________? A. urad dal B. moong dal C. wheat D. rice 7. BJP will kick off it’s 75-day ‘Parivartan Yatra‘ in? A. Karnataka B. Himachal Pradesh C. Gujrat D. Punjab 8. Which Indian Footwear company opened it’s IPO for public subscription? A. Paragon B. Lancer C. Khadim’s D. Bata Note: The Information Provided here is only for reference. It May vary the Original. www.sarkariresults.io 9. Who was appointed as the Consul General of Korea? A. Narayan Murthy B. Suresh Chukkapalli C. Aziz Premji D. Prashanth Iyer 10. Vikas Seth was appointed as the CEO of? A. LIC of India B. Birla Sun Life Insurance C. Bharathi AXA Life Insurance D. HDFC 11. Who is the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh? A. Babulal gaur B. Shivraj Singh Chouhan C. Digvijaya Singh D. Uma Bharati 12. Who is the Railway Minister of India? A. Piyush Goyal B. Dr. Harshvardhan C. Suresh Prabhu D. Ananth Kumar Hegade 13. -

The Forms of Seeking Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language

THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 T.U. Reg. No.:9-2-540-164-2010 Date of Approval Thesis Fourth Semester Examination Proposal: 18/12/2017 Exam Roll No.: 28710094/072 Date of Submission: 30/05/2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that to the best of my knowledge this thesis is original; no part of it was earlier submitted for the candidate of research degree to any university. Date: ..…………………… Jyoti Kaushal i RECOMMENDATION FOR ACCEPTANCE This is to certify that Miss Jyoti Kaushal has prepared this thesis entitled The Forms of Seeking, Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language under my guidance and supervision I recommend this thesis for acceptance Date: ………………………… Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav Reader Department of English Education Faculty of Education TU, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal ii APPROVAL FOR THE RESEARCH This thesis has been recommended for evaluation from the following Research Guidance Committee: Signature Dr. Prem Phyak _______________ Lecturer & Head Chairperson Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav (Supervisor) _______________ Reader Member Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. -

Genealogical Classification of New Indo-Aryan Languages and Lexicostatistics

Anton I. Kogan Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Russia, Moscow); [email protected] Genealogical classification of New Indo-Aryan languages and lexicostatistics Genetic relations among Indo-Aryan languages are still unclear. Existing classifications are often intuitive and do not rest upon rigorous criteria. In the present article an attempt is made to create a classification of New Indo-Aryan languages, based on up-to-date lexicosta- tistical data. The comparative analysis of the resulting genealogical tree and traditional clas- sifications allows the author to draw conclusions about the most probable genealogy of the Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords: Indo-Aryan languages, language classification, lexicostatistics, glottochronology. The Indo-Aryan group is one of the few groups of Indo-European languages, if not the only one, for which no classification based on rigorous genetic criteria has been suggested thus far. The cause of such a situation is neither lack of data, nor even the low level of its historical in- terpretation, but rather the existence of certain prejudices which are widespread among In- dologists. One of them is the belief that real genetic relations between the Indo-Aryan lan- guages cannot be clarified because these languages form a dialect continuum. Such an argu- ment can hardly seem convincing to a comparative linguist, since dialect continuum is by no means a unique phenomenon: it is characteristic of many regions, including those where Indo- European languages are spoken, e.g. the Slavic and Romance-speaking areas. Since genealogi- cal classifications of Slavic and Romance languages do exist, there is no reason to believe that the taxonomy of Indo-Aryan languages cannot be established.