Chapter 36. Grammatical Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

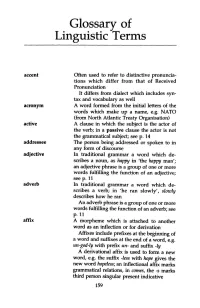

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

ENGLISH AS an ANALYTIC LANGUAGE – the Importance of Word Order

ENGLISH AS AN ANALYTIC LANGUAGE – the importance of word order In linguistic typology, an analytic language is a language that primarily conveys relationships between words in sentences by way of helper words (particles, prepositions, etc.) and word order, as opposed to utilizing inflections (changing the form of a word to convey its role in the sentence) (Wiki) AFFIRMATIVE SENTENCES subject verb(s) object I speak English I can speak English subject verb(s) indirect object direct object place time I will tell you the story at school tomorrow. NEGATIVE SENTENCE The word order in negative sentences is the same as in affirmative sentences. Note, however, that in negative sentences we usually need an auxiliary verb*: subject verbs indirect object direct object place time I will not tell you the story at school tomorrow. *An auxiliary verb helps the main (full) verb and is also called a "helping verb." With auxiliary verbs, you can write sentences in different tenses, moods, or voices. Auxiliary verbs are: be, do, have, will, shall, would, should, can, could, may, might, must, ought, etc. INTERROGATIVE SENTENCES In questions, the word order subject-verbs-object is the same as in affirmative sentences. The only thing that is different is that you usually have to put the auxiliary verb (or the main verb “be”) before the subject. Interrogatives (Question Words) are put at the beginning of the sentences: interrogative auxiliary *verb subject other verb(s) indirect object direct object place time What would you like to tell me Did you have a party in your flat yesterday? When were you here? Question Words in English The most common question words in English are the following: WHO is only used when referring to people. -

To Ba Or Not to Ba Differential Object Marking in Chinese

î To ba or not to ba Differential Object Marking in Chinese Geertje van Bergen I To ba or not to ba Differential Object Marking in Chinese Geertje van Bergen PIONIER Project Case Cross-linguistically Department of Linguistics Radboud University Nijmegen P.O. Box 9103 6500 HD Nijmegen the Netherlands www.ru.nl/pionier [email protected] III To ba or not to ba Differential Object Marking in Chinese Master’s Thesis General Linguistics Faculty of Arts Radboud University Nijmegen November 2006 Geertje van Bergen 0136433 First supervisor: Dr. Helen de Hoop Second supervisor: Prof. Dr. Pieter Muysken V Acknowledgements I would like to thank Lotte Hogeweg and the members of the PIONIER-project Case Cross-linguistically for the nice cooperation during the past year; many thanks go to Monique Lamers for the pleasant teamwork. I am especially grateful to Yangning for the close cooperation in Beijing and Nijmegen, which has laid the foundation of ¡ £¢ this thesis. Many thanks also go to Sander Lestrade for clarifying conversations over countless cups of coffee. I would like to thank Pieter Muysken for his willingness to be my second supervisor and for his useful comments on an earlier version. Also, I gratefully acknowledge the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research (NWO) for financial support, grant 220-70-003, principal investigator Helen de Hoop (PIONIER-project ‘Case cross-linguistically’). Especially, I would like to thank Helen de Hoop for her great support and supervision, for keeping me from losing courage and keeping me on schedule, for her indispensable comments and for all the opportunities she offered me to develop my research skills. -

Variation in the Ergative Pattern of Kurmanji Songül Gündoğdu, Muş

Variation in the Ergative Pattern of Kurmanji Songül Gündoğdu, Muş Alparslan University, Muş, Turkey LANGUAGE KEYWORDS: Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji) AREA KEYWORDS: Middle East (Turkey) ABSTRACT (ENGLISH) Kurdish-Kurmanji (or Northern Kurdish) belongs to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. This study is dedicated to a deeper understanding of a specific grammatical feature typical of Kurmanji: the ergative structure. Based on the example of this core structure, and with empirical evidence from the Kurmanji dialect of Muş in Turkey, I will discuss the issues of variation and change in Kurmanji, more precisely the ongoing shift from ergative to nominative-accusative structures. The causes for such a fundamental shift, however, are not easy to define. The close historical vicinity to Turkish and Armenian might be a trigger for the shift; another trigger is language-internal (diachronic) change. In sum, the investigated variation sheds light on a fascinating grammatical change in a language that is also sociopolitically in a situation of constant change, movement, and upheaval. ABSTRACT (DEUTSCH) Kurdisch-Kurmanci (oder Nordkurdisch) gehört zum iranischen Zweig der indoeuropäischen Sprachfamilie. Eine zentrale und charakteristische grammatische Struktur dieser Sprache ist der Ergativ; ihm ist der vorliegende Beitrag gewidmet. Am Beispiel des Ergativ werde ich Variation und Wandel im Kurmanci diskutieren und insbesondere auf den Dialekt von Muş (Türkei) eingehen. Dabei zeigt sich, dass sich derzeit im Kurmanci der Wandel von einer Ergativ- zu einer Nominativ-Akkusativ-Sprache vollzieht. Die Ursachen für einen derart grundlegenden Wandel sind nicht leicht zu benennen. Ein Grund mag in der schon historisch engen Nachbarschaft zum Türkischen und Armenischen liegen; ein anderer Grund mag im sprach-internen (diachronen) Wandel des Kurmanci selbst zu finden sein. -

Analytic and Cognitive Language in Instagram Captions

ISSN 2474-8927 SOCIAL BEHAVIOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE Open Journal Brief Research Report What Were They Thinking? Analytic and Cognitive Language in Instagram Captions Sheila Brownlow, PhD1*; Makenna Pate, BA2; Abigail Alger, BA [Student]2; Natalie Naturile, BA2 1Department of Psychology, Catawba College, Salisbury NC 28144, USA *Corresponding author Sheila Brownlow, PhD Professor and Chair, Department of Psychology, Catawba College, Salisbury NC 28144, USA; E-mail: [email protected] Article Information Received: June 15th, 2019; Revised: July 8th, 2019; Accepted: July 15th, 2019; Published: July 16th, 2019 Cite this article Brownlow S, Pate M, Alger A, Naturile N. What were they thinking? Analytic and cognitive language in Instagram captions. Soc Behav Res Pract Open J. 2019; 4(1): 21-25. doi: 10.17140/SBRPOJ-4-117 ABSTRACT Background We examined content and expression of Instagram captions of major celebrities who differed according to sex and status, with a focus on determining whether these variables influenced the use of analytic language and cognitive content. Method Instagram captions (n=942) were analyzed with the linguistic inquiry and word count (LIWC), which delineated percentage of language reflecting analytical thought and various cognitive mechanisms, such as causality and discrepancy. Results Men and low-status persons used more functional analytic language, demonstrating critical thought; in contrast, high-status celeb- rities showed more causality. Women more than men “qualified” their speech with discrepancy. These findings were not a function of sentence length. Conclusion Status increased the tendency to construct and explain, perhaps because higher status celebrities (particularly women) knew that they could hold followers’ attention with complex content. -

Hybridity Versus Revivability

40 Hybridity versus revivability HYBRIDITY VERSUS REVIVABILITY: MULTIPLE CAUSATION, FORMS AND PATTERNS Ghil‘ad Zuckermann Abstract The aim of this article is to suggest that due to the ubiquitous multiple causation, the revival of a no-longer spoken language is unlikely without cross-fertilization from the revivalists’ mother tongue(s). Thus, one should expect revival efforts to result in a language with a hybridic genetic and typological character. The article highlights salient morphological constructions and categories, illustrating the difficulty in determining a single source for the grammar of Israeli, somewhat misleadingly a.k.a. ‘Modern Hebrew’. The European impact in these features is apparent inter alia in structure, semantics or productivity. Multiple causation is manifested in the Congruence Principle, according to which if a feature exists in more than one contributing language, it is more likely to persist in the emerging language. Consequently, the reality of linguistic genesis is far more complex than a simple family tree system allows. ‘Revived’ languages are unlikely to have a single parent. The multisourced nature of Israeli and the role of the Congruence Principle in its genesis have implications for historical linguistics, language planning and the study of language, culture and identity. “Linguistic and social factors are closely interrelated in the development of language change. Explanations which are confined to one or the other aspect, no matter how well constructed, will fail to account for the rich body of -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

Modeling Infant Segmentation of Two Morphologically Diverse Languages

Modeling infant segmentation of two morphologically diverse languages Georgia Rengina Loukatou1 Sabine Stoll 2 Damian Blasi2 Alejandrina Cristia1 (1) LSCP, Département d’études cognitives, ENS, EHESS, CNRS, PSL Research University, Paris, France (2) University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland [email protected] RÉSUMÉ Les nourrissons doivent trouver des limites de mots dans le flux continu de la parole. De nombreuses études computationnelles étudient de tels mécanismes. Cependant, la majorité d’entre elles se sont concentrées sur l’anglais, une langue morphologiquement simple et qui rend la tâche de segmen- tation aisée. Les langues polysynthétiques - pour lesquelles chaque mot est composé de plusieurs morphèmes - peuvent présenter des difficultés supplémentaires lors de la segmentation. De plus, le mot est considéré comme la cible de la segmentation, mais il est possible que les nourrissons segmentent des morphèmes et non pas des mots. Notre étude se concentre sur deux langues ayant des structures morphologiques différentes, le chintang et le japonais. Trois algorithmes de segmentation conceptuellement variés sont évalués sur des représentations de mots et de morphèmes. L’évaluation de ces algorithmes nous mène à tirer plusieurs conclusions. Le modèle lexical est le plus performant, notamment lorsqu’on considère les morphèmes et non pas les mots. De plus, en faisant varier leur évaluation en fonction de la langue, le japonais nous apporte de meilleurs résultats. ABSTRACT A rich literature explores unsupervised segmentation algorithms infants could use to parse their input, mainly focusing on English, an analytic language where word, morpheme, and syllable boundaries often coincide. Synthetic languages, where words are multi-morphemic, may present unique diffi- culties for segmentation. -

Interrogating Possessive Have: a Case Study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó

99 József Andor: Interrogating possessive have: a case study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó József Andor Interrogating possessive have: a case study Abstract Major, standard grammars of English give an account and interpret interrogatively used possessive have as a unique specialty of genres and text types of British English. Reviewing descriptions offered by some of these grammars and presenting empirically based evidence on acceptability of usage and function, the present paper offers results revealing the occurrence of inverted possessive have in other regional varieties, specifically in American English. It is suggested that have, retaining its possessive lexical meaning behaves as a semi-auxiliary in such constructions. Keywords: possessive, inversion, do-support, corpus-based, semi-auxiliary, notionally and morpho-syntactically based categorization 1 Introduction What made me start researching the functional-semantic and pragmatic-contextual force of interrogative sentences with the possessive lexical status of have was finding the example Have you a pen? on page 88 of the recently published Oxford Modern English Grammar authored by Bas Aarts (2011). The sentence was given under section 4.1.1.6. titled “Subjects invert positions with verbs in interrogative main clauses”, which section, due to its scope, did not address discussing syntactic variation concerning possessive usage of have, contrasting syntactic as well as cognitive-semantic and pragmatic, usage based issues of formally pure cases of inversion with the co-occurrence of have and do-support (also called do-periphrasis) or the have got construction. This came to me as a surprise, as types of have-based possession could have been discussed in a dictionary based on one of the most valuable corpora of British English, the British component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB). -

*65 EØ RS Mitipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P

1100&*430 ERIC RE PeRT .RESUNE IEO 010 -t-60 1W,29Hib 24 (REV) USSGE IIANUAL:44LANGUAGE CUUICIMUK. I AND !I TEACHER V ER&Iet4, ZHAER4ALURTAWR RaR610280 UNC.VERSITY OE ORE?, -EUGENE Cit9+1*114114411 1111409,40116.C431 . *65 EØ RS MiTipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P. *GRAMM-0..111GhTH- IIRAINEV.- sevens .'GRADEs. vitiCIINUCAILOCSUIDESS *TIEAZINING- SUIDESL 11-YEAL4IVIL 61/10Ett. TiENGLISK EWEN/v; MESONV4-PROJECIr'ENG11314-- RE* GRAM* A IIANUSL, GRINAR- WAGE WAS PRIEN*.f.a *OR- -TEACHINC,1semoffspoi, AND EIGHTIWERMSE- MOMS .CARINECULUNS.- THEP-MANUAt 11111S44R,-TEAT;NERWAIND CONTAINS1 96 ' GRIMMAR_ USAGEWITEett -*WOE 4-1111111), 4ItykiPROF1TSO1Y,-:TRENNIED: .4N SENENTWAID: E IGHTW GRAvegq: THE7COIITEInt-41ave-litst ,i4MIANGEO- ALAINACITICALLY-41101 A GAUt MOM '41F- -CROSSMIEFERENEU,-311EIMINUAL -414--STIODENT 4111.11NADVE_':OP-.4=UNISSORMATI.-4.14AL'IMAPSIAL--Te MEGRIM: -47 NTH SUER- -ALIPECTS 1iI E 1INGUSH 7CURRICARAIMIAN ACCOMPANYING MANUAL WAS ?NEPA-RED FOR -STUOEUT USE :4110,-010 :ant; IMO el OREGON etlittfAcilLatIM 5.xuuY CINTER **0 014 VELEM IL SiDEPARTMENT OFHEMplti: MICATION v-4 Office cif Echkgati On d**filthy has beenreproduced exactlyslitectile Co This document Points Of VieW OrOPielone organizationoriginating It. v-1 person or represent OMNIOff Ice etEducation stated donot necessarily CI position or policy. C) I USAGE ISAIWATe !ammo Curriculum I Mid II Teacher I/onion The project reported hereinwas -supported through the Cooperative ResearchPrograxa of- the Office of Education, U, S. Departgle4totilealt4s Education, and Welfare USAGE MANUAL TABLE OFCONTENTS Etas Abbreviations 1 Bust for burst Accent- Except 3. CapitalCapitol a Adjective 1 Capitalization 9 Adverb 2 Case 10 I Advice- Advise 2 clothsClothes 11 Affect- Effect 3 Colon 11 Agreement 3 Comma 11 Ain't 5 Almost-Most' 5 ConjUnction 11 Already-All ready 5 Contractions 12 All right 5 tOundil- Counsel 12 Altogether - All together 5 toUrse-Coarse 12 Among- Between 6 DetertDessert 12 ft.n-And 6 Determiner 13 Antecedent 6 ed -bove 13 t Apostrophe 6 Done foi-' did 18 Appositive 7 Negative 14 s.