A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognition and Tagging of Compound Verb Groups in Czech

In: Proceedings of CoNLL-2000 and LLL-2000, pages 219-225, Lisbon, Portugal, 2000. Recognition and Tagging of Compound Verb Groups in Czech Eva Zgt~kov~ and Lubo~ Popelinsk:~ and Milo~ Nepil NLP Laboratory, Faculty of Informatics, Masaryk University Botanick£ 68, CZ-602 00 Brno, Czech Republic {glum, popel, nepil}@fi.muni.cz Verb groups are often split into more parts with so called gap words. In the second verb group Abstract the gap words are o td konferenci (about the In Czech corpora compound verb groups are conference). In annotated Czech corpora, in- usually tagged in word-by-word manner. As a cluding DESAM (Pala et al., 1997), compound consequence, some of the morphological tags of verb groups are usually tagged in word-by-word particular components of the verb group lose manner. As a consequence, some of the morpho- their original meaning. We present a method for logical tags of particular components of the verb automatic recognition of compound verb groups group loose their original meaning. It means in Czech. From an annotated corpus 126 def- that the tags are correct for a single word but inite clause grammar rules were constructed. they do not reflect the meaning of the words in These rules describe all compound verb groups context. In the above sentence the word jsem that are frequent in Czech. Using those rules is tagged as a verb in present tense, but the we can find compound verb groups in unanno- whole verb group to which it belongs - jsem tated texts with the accuracy 93%. Tagging nev~d~la - is in past tense. -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

A Japanese Compound Verb V -Te-Iku and Event Composition Eri Tanaka* 2-1869-14, Higashi-Guminoki, Osakasayama, Osaka, Japan Eri-Tanarit)Rj 8

A Japanese Compound Verb V -te-iku and Event Composition Eri Tanaka* 2-1869-14, Higashi-guminoki, Osakasayama, Osaka, Japan eri-tanarit)rj 8. s o-net. ne. j p 1. Introduction It is widely recognized that Japanese manner of motion verbs do not tolerate a so-called GOAL expression -ni, as observed in (1) (see e.g. Yoneyama (1986), Kageyama and Yumoto (1997), Ueno and Kageyama (2000)). 1' 2 The same is true of Korean (cf. Lee (1999)). (1) Japanese: a. *?Taro wa gakko-ni arui-ta Taro TOP school-GOAL walk-PAST `(Lit.)Taro walked to school' b. *?Taro wa gakko-ni hasi-tta Taro TOP school-GOAL run-PAST `(Lit.)Taro ran to school' Korean: c. *?Taro-nun yek-e keless-ta Taro-TOP station-GOAL walk-PAST `(Lit.)Taro walked to the station' d. *?Taro yek-e tallyess-ta Taro-TOP station-GOAL run-PAST `(Lit.)Taro ran to the station' On the other hand, in English, the expressions corresponding to (1) are natural. (2) a. John walked to school. b. John ran to school. The intended situations in (2) should be realized in Japanese with a V-V compound or a V-te-V compound, such as arui-te-iku `go by walking' and hasi-tte-iku 'go by running'. In Korean, as in Japanese, we should use compound verbs. We will call V -te-V compounds in Japanese TE-compounds, to distinguish them from V-V compounds. 3' 4 * I would like to express my deep gratitude to Prof. Chungmin Lee for kindly giving me advice. -

Chapter Ii the Types of Phrasal Verbs in Movie Snow White and the Huntsman by Rupert Sanders

33 CHAPTER II THE TYPES OF PHRASAL VERBS IN MOVIE SNOW WHITE AND THE HUNTSMAN BY RUPERT SANDERS In this chapter, the researcher will analyzed the types of phrasal verbs. It is to complete the first question in this research. The researcher had been categorizing the types of phrasal verbs and form that divided into verb and adverb, also sometimes prepositions. 2.1. Types of Phrasal Verbs in movie Snow White and the Huntsman According to Heaton (1985:103) considers that phrasal verbs are compound verbs that result from combining a verb with an adverb or a preposition, the resulting compound verb being idiomatic. Phrasal verb is one of important part of grammar that almost found in English language. Based on Andrea Rosalia in her book “A Holistic Approach to Phrasal Verb”, Phrasal verbs are considered to be a very important and frequently occurring feature of the English language. First of all, they are so common in every day conversation, and non-native speakers who wish to sound natural when speaking this language need to learn their grammar in order to know how to produce them correctly. Secondly, the habit of inventing phrasal verbs has been the source of great enrichment of the language (Andrea Rosalia, 2012:16). A grammarian such as Eduard, Vlad (1998:93) describes phrasal verbs as "combinations of a lexical verb and adverbial particle". It means that the verb if wants to be a phrasal verb always followed by particle. It can be one particle or two particles in one verb. If the case is like that, it called as multi word verbs. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

SYNTAX MASTER LIST Semester 2

NOUN SYNTAX Syntax Explanation Latin I Latin II NOMINATIVE Subject The actor of an active verb, receiver of a passive verb, or “it” of an impersonal/stative verb ✓ ✓ Predicate The noun renames the subject via sum, esse ✓ ✓ GENITIVE Possession The genitive owns the noun to which it is connected (sometimes via sum, esse) ✓ ✓ Material The noun is made up of this genitive ✓ Quality The genitive gives a characteristic of the noun (requires attributive adjective) ✓ Partitive The genitive is made up of this noun ✓ Objective The genitive receives the noun as its object ✓ With Adjective The genitive is connected to an adjective ✓ With Verb The genitive is connected to a verb (verbs of reminding, accusing, condemning, feeling, etc.) ✓ Value The genitive indicates how important is an object ✓ DATIVE Indirect Object The dative receives the direct object (explicit or implicit [intransitives/compounds]) ✓ ✓ Possession The dative owns the noun to which it is connected via sum, esse ✓ Agent The dative indicates the actor of a passive verb (typically with gerundives or compoundeds) ✓ Reference The dative indicates to whom, or for whom, a statement refers or is of interest ✓ Ethical A subset of reference, typically used with person pronoun to show interested felt by a person Separation The dative indicates motion away (it has no preposition and is used with verbs of taking away) ✓ Purpose or End The dative indicates the reason for an action ✓ With Adjective The dative is connected to an adjective ✓ With Verb Another name for the dative indirect object -

The Dilemma of Learning Phrasal Verbs Among EFL Learners

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 www.alls.aiac.org.au The Dilemma of Learning Phrasal Verbs among EFL Learners Salman A. Al Nasarat Language Center, Al Hussein Bin Tala University, Jordan Corresponding Author: Salman A. Al Nasarat, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This study was designed to examine difficulties in interpreting English phrasal verbs (PVs) Received: December 25, 2017 that individual college student of English face during their academic career. Interpretation Accepted: March 07, 2018 is an apparent obstacle that Jordanian English students encounter as they learn language Published: April 30, 2018 systematically. The learners being investigated were divided into two groups including regular Volume: 9 Issue: 2 students of English language and literature and non-majoring English students who study Advance access: March 2018 communication skills in English at Al Hussein Bin Talal University. Basically, the present study attempted to investigate students’ background level and performance to identify the source of weakness in interpreting PVs either orally or based on written texts. The findings would shed Conflicts of interest: None light on translating inability and more significantly on interpreting strategies while students work Funding: None out the meaning of spoken or written PVs combinations. The overall score obtained by students in the designed test resulted in a plausible explanation for this learning problem and should help for a better course design and instruction as well as effective classroom teaching and curricula. Key words: Translation, Phrasal Verbs, Interpreting, EFL, Jordanian Students INTRODUCTION intelligibility of two or more languages. One important issue Translation is described as the process of translating words or regarding interpreting is dealing with English two-part verbs. -

Sentence Diagraming

GLENCOE LANGUAGE ARTS Sentence Diagraming To the Teacher Sentence Diagraming is a blackline master workbook that offers samples, exercises, and step-by-step instructions to expand students’ knowledge of grammar and sentence structure. Each lesson teaches a part of a sentence and then illustrates a way to diagram it. Designed for students at all levels, Sentence Diagraming provides students with a tool for understanding written and spoken English. Glencoe/McGraw-Hill Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to reproduce the material contained herein on the condition that such material be reproduced only for classroom use; be provided to students, teachers, and families without charge; and be used solely in conjunction with Glencoe Language Arts products. Any other reproduction, for use or sale, is prohibited without written permission of the publisher. Send all inquiries to: Glencoe/McGraw-Hill 8787 Orion Place Columbus, Ohio 43240 ISBN 0-07-824702-0 Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 045 04 03 02 01 00 PART I Simple Sentences . 1 Lesson 1 Simple Subjects and Simple Predicates I. 2 Simple subject and simple predicate Understood subject Lesson 2 Simple Subjects and Simple Predicates II . 3 Simple subject or simple predicate having more than one word Simple subject and simple predicate in inverted order Lesson 3 Compound Subjects and Compound Predicates I . 5 Compound subject Lesson 4 Compound Subjects and Compound Predicates II . 6 Compound predicate Lesson 5 Compound Subjects and Compound Predicates III . 7 Compound subject and compound predicate Lesson 6 Direct Objects and Indirect Objects I . -

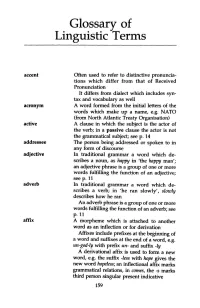

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

State Verb, Action Verb and Noun in the State Run Colleges in Pakistan

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 6, No. 5; 2016 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education A Study on Science Students’ Understanding of Three Lemmas: State Verb, Action Verb and Noun in the State Run Colleges in Pakistan Muhamma Imran1, Tahira Asgher2 & Mamuna Ghani3 1 Govt. Post Graduate College, Burewala, Pakistan 2 Govt. Sadiq College Women University, Bahawalpur, Pakistan 3 Department of English, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan Correspondence: Tahira Asgher, Govt Sadiq College Women University, Bahawalpur, Pakistan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 25, 2016 Accepted: August 16, 2016 Online Published: September 23, 2016 doi:10.5539/ijel.v6n5p121 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v6n5p121 Abstract English main verbs are classified as stative and dynamic. At first, this paper deals with the analysis of stative verbs, highlights their true nature and function and illustrates the concept of spontaneity within the state verbs. Secondly, it expounds how the term ‘lemma’ helps in sorting out the same words representing different parts of speech. Finally, it reports on the level of the science students’ competency in the use of state verbs, action verbs and nouns. For this purpose, 300 science students of intermediate level were selected as participants for the present study. A language proficiency test was conducted to collect data. The results revealed that majority of the students had scanty understanding of nouns and state verbs but their recognition of action verbs had been of average level. Some suggestions for improved pedagogy in teaching English grammar have been suggested on the basis of these findings. -

Vs. Object Marker /Ta

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 7, pp. 1081-1092, July 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.7.1081-1092 On the Usage of Sinhalese Differential Object Markers Object Marker /wa/ vs. Object Marker /ta/ Kanduboda A, B. Prabath Ritsumeikan University, Ritsumeikan International, Global Gateway Program, Japan Abstract—Previous studies (Aisen, 2003; Kanduboda, 2011) on Sinhalese language have suggested that direct objects (i.e., accusative marked nouns) in active sentences can be marked by two distinctive case markers. In some sentences, accusative nouns can be denoted by the accusative case marker /wa/. In other sentences, the same nouns can again be denoted by the dative case marker /ta/. However, the verbs required by these accusatives were not investigated in the previous studies. Thus, the present study further conducted an investigation to observe whether these two types of case markings can occur with the same verbs. A free productivity task was conducted with 100 Sinhalese native speakers living in Sri Lanka. A comparison study was carried out using sentences with the verbs accompanying /wa/ accusatives and /ta/ accusatives. The results showed that, verbs accompanied by /wa/ case marker and verbs accompanied by /ta/ case marker are incongruent. Thus, this study concluded that Sinhalese active sentences consisting of transitive verbs are broadly divided into two patterns; those which take only /wa/ accusatives and those which take only /ta/ accusatives. Index Terms—Sinhalese language, active sentences, transitive verbs, /wa/ accusatives, /ta/ accusatives I. INTRODUCTION Sinhalese (also referred to as Sinhala, Singhala and Singhalese, (Englebretson & Carol, 2005)) is one of the major languages spoken in Sri Lanka. -

Change of Location and Change of State: How Telicity Is Attained

PACLIC 24 Proceedings 885 Change of Location and Change of State: How Telicity is Attained Chungmin Lee Department of Linguistics, Seoul National University Seoul 151-742, Korea [email protected] Abstract. This paper basically discusses parallels between change of location (or space) and change of state. Change of state is analogous to change of location, involving an abstract state Source and an abstract state Goal with abstract Path, involving telicity and showing alternations crosslinguistically. Spatial change is least abstract, whereas temporal change and state change are more abstract and psychological change is most abstract, exhibiting various phenomena of degree modification and telicity differentiations. Abstraction causes argument reduction and change in syntactic behavior. State-oriented predicates are modified by the equivalents of the degree modifier very and process-oriented ones by the quality modifier well and its equivalents. Keywords: change of location, change of state, creation/removal, telicity, degree, Generative Lexicon Theory 1. Introduction1 This paper discusses parallels between change of location and change of state, involved in locomotive (=motion), change of state, and creation/removal verbs, trying to see how telicity is attained semantically, examining cross-linguistic typological variation in lexical patterning and some syntactic behaviors. First, spatial uses of prepositions or postpositions are closely connected with temporal uses of them, although the latter are more abstract and limited because of directionality and dimensionality. Second, change of state (qualities) is structurally associated with change of location, with its Source and Goal. Change always means a shift from ¬P to P in state as well as in location through the flow of time.