Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer Learning for Singlish Universal Dependencies Parsing and POS Tagging

From Genesis to Creole language: Transfer Learning for Singlish Universal Dependencies Parsing and POS Tagging HONGMIN WANG, University of California Santa Barbara, USA JIE YANG, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore YUE ZHANG, West Lake University, Institute for Advanced Study, China Singlish can be interesting to the computational linguistics community both linguistically as a major low- resource creole based on English, and computationally for information extraction and sentiment analysis of regional social media. In our conference paper, Wang et al. [2017], we investigated part-of-speech (POS) tagging and dependency parsing for Singlish by constructing a treebank under the Universal Dependencies scheme, and successfully used neural stacking models to integrate English syntactic knowledge for boosting Singlish POS tagging and dependency parsing, achieving the state-of-the-art accuracies of 89.50% and 84.47% for Singlish POS tagging and dependency respectively. In this work, we substantially extend Wang et al. [2017] by enlarging the Singlish treebank to more than triple the size and with much more diversity in topics, as well as further exploring neural multi-task models for integrating English syntactic knowledge. Results show that the enlarged treebank has achieved significant relative error reduction of 45.8% and 15.5% on the base model, 27% and 10% on the neural multi-task model, and 21% and 15% on the neural stacking model for POS tagging and dependency parsing respectively. Moreover, the state-of-the-art Singlish POS tagging and dependency parsing accuracies have been improved to 91.16% and 85.57% respectively. We make our treebanks and models available for further research. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Copular Sentences*

A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF COPULAR SENTENCES* Masato Niimura Nanzan University 1. Introduction Copular is a verb whose main function is to link subjects with predicate complements. In a limited sense, the copular refers to a verb that does not have any semantic content, but links subjects and predicate complements. In a broad sense, the copular contains a verb that has its own meaning and bears the syntactic function of “the copular.” Higgins (1979) analyses English copular sentences and classifies them into three types. (1) a. predicational sentence b. specificational sentence c. identificational sentence Examples are as follows: (2) a. John is a philosopher. b. The bank robber is John Smith. c. That man is Mary’s brother. (2a) is an example of predicational sentence. This type takes a reference as subject, and states its property in predicate. In (2a), the reference is John, and its property is a philosopher. (2b) is an example of specificational sentence, which expresses what meets a kind of condition. In (2b), what meets the condition of the bank robber is John Smith. (2c) is an example of identificational sentence, which identifies two references. This sentence identifies that man and Mary’s brother. * This paper is part of my MA thesis submitted to Nanzan University in March, 2007. This paper was also presented at the Connecticut-Nanzan-Siena Workshop on Linguistic Theory and Language Acquisition, held at Nanzan University on February 21, 2007. I would like to thank the participants for the discussions and comments on this paper. My thanks go to Keiko Murasugi, Mamoru Saito, Tomohiro Fujii, Masatake Arimoto, Jonah Lin, Yasuaki Abe, William McClure, Keiko Yano and Nobuko Mizushima for the invaluable comments and discussions on the research presented in this paper. -

Universidaddesonora

U N I V E R S I D A D D E S O N O R A División de Humanidades y Bellas Artes Maestría en Lingüística Nominal and Adjectival Predication in Yoreme/Mayo of Sonora and Sinaloa TESIS Que para optar por el grado de Maestra en Lingüística presenta Rosario Melina Rodríguez Villanueva 2012 Universidad de Sonora Repositorio Institucional UNISON Excepto si se seala otra cosa, la licencia del tem se describe como openAccess CONTENTS DEDICATION……………………………………………………………………….. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………….. 5 ABBREVIATIONS………………………………………………………………….. 7 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………… 12 CHAPTER 1: The Yoreme/Mayo and their language……………………………….. 16 1.1 Ethnographic and Sociolinguistic Context………………………………………. 16 1.1.1 Geographic Location of the Yoreme/Mayo…………………………………… 16 1.1.2 Social Organization of the Yoreme/Mayo……………………………………... 20 1.1.3 Economy and Working Trades………………………………………………… 21 1.1.4 Religion and Cosmogony……………………………………………………… 22 1.2 The Yoreme/Mayo language…………………………………………………….. 23 1.2.1 Geographical location and genetic affiliation………………………………….. 23 1.2.2 Phonology……………………………………………………………………… 27 1.2.2.1 Consonants………………………………………………………………….. 27 1.2.2.2 Vowels……………………………………………………………………….. 30 1.2.3 Typological Characteristics……………………………………………………. 33 1.2.3.1 Classification………………………………………………………………… 33 1.2.3.2 Marking: head or dependent?........................................................................... 35 1.2.3.3 Word Order…………………………………………………………………. 40 1.2.3.4 Case-Marking………………………………………………………………. 43 1.3 Previous Documentation and Description of Yoreme/Mayo……………………. 48 1 CHAPTER 2: Theoretical Preliminaries…………………………………………….. 52 2.0 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… 52 2.1 Predication: Verbal and Non-verbal 53 2.1.1 Definition………………………………………………………………………. 53 2.1.2 Verbal Predication……………………………………………………………. 56 2.1.3 Non-verbal Predication………………………………………………………… 61 2.2. The Syntax of Non-verbal Predication………………………………………… 71 2.2.1 Nominal Predication…………………………………………………………. -

A Grammar of Gyeli

A Grammar of Gyeli Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) eingereicht an der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von M.A. Nadine Grimm, geb. Borchardt geboren am 28.01.1982 in Rheda-Wiedenbrück Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jan-Hendrik Olbertz Dekanin der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1. 2. Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Table of Contents List of Tables xi List of Figures xii Abbreviations xiii Acknowledgments xv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Gyeli Language . 1 1.1.1 The Language’s Name . 2 1.1.2 Classification . 4 1.1.3 Language Contact . 9 1.1.4 Dialects . 14 1.1.5 Language Endangerment . 16 1.1.6 Special Features of Gyeli . 18 1.1.7 Previous Literature . 19 1.2 The Gyeli Speakers . 21 1.2.1 Environment . 21 1.2.2 Subsistence and Culture . 23 1.3 Methodology . 26 1.3.1 The Project . 27 1.3.2 The Construction of a Speech Community . 27 1.3.3 Data . 28 1.4 Structure of the Grammar . 30 2 Phonology 32 2.1 Consonants . 33 2.1.1 Phonemic Inventory . 34 i Nadine Grimm A Grammar of Gyeli 2.1.2 Realization Rules . 42 2.1.2.1 Labial Velars . 43 2.1.2.2 Allophones . 44 2.1.2.3 Pre-glottalization of Labial and Alveolar Stops and the Issue of Implosives . 47 2.1.2.4 Voicing and Devoicing of Stops . 51 2.1.3 Consonant Clusters . -

Copula-Less Nominal Sentences and Matrix-C Clauses: a Planar View Of

Copula-less Nominal Sentences and Matrix-C0 Clauses: A Planar View of Clause Structure * Tanmoy Bhattacharya Abstract This paper is an attempt to unify the apparently unrelated sentence types in Bangla, namely, copula-less nominal sentences and matrix-C clauses. In particular, the paper claims that a “Planar” view of clause structure affords us, besides the above unification, a better account of the Kaynean Algorithm (KA, as in Kayne (1998a, b; 1999)) in terms of an interface driven motivation to break symmetry. In order to understand this unification, the invocation of the KA, that proclaims most significantly the ‘non-constituency’ of the C and its complement, is relevant if we agree with the basic assumption of this paper that views both Cs and Classifiers as disjoint from the main body (plane) of the clause. Such a disjunction is exploited further to introduce a new perspective of the structure of clauses, namely, the ‘planar’ view. The unmistakable non-linearity of the KA is seen here as a multi-planar structure creation; the introduction of the C/ CLA thus implies a new plane introduction. KA very strongly implies a planar view of clause structure. The identification of a plane is considered to be as either required by the C-I or the SM interface and it is shown that this view matches up with the duality of semantics, as in Chomsky (2005). In particular, EM (External Merge) is required to introduce or identify a new plane, whereas IM (Internal Merge) is inter- planar. Thus it is shown that inter-planar movements are discourse related, whereas intra-planar movements are not discourse related. -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

NWAV 46 Booklet-Oct29

1 PROGRAM BOOKLET October 29, 2017 CONTENTS • The venue and the town • The program • Welcome to NWAV 46 • The team and the reviewers • Sponsors and Book Exhibitors • Student Travel Awards https://english.wisc.edu/nwav46/ • Abstracts o Plenaries Workshops o nwav46 o Panels o Posters and oral presentations • Best student paper and poster @nwav46 • NWAV sexual harassment policy • Participant email addresses Look, folks, this is an electronic booklet. This Table of Contents gives you clues for what to search for and we trust that’s all you need. 2 We’ll have buttons with sets of pronouns … and some with a blank space to write in your own set. 3 The venue and the town We’re assuming you’ll navigate using electronic devices, but here’s some basic info. Here’s a good campus map: http://map.wisc.edu/. The conference will be in Union South, in red below, except for Saturday talks, which will be in the Brogden Psychology Building, just across Johnson Street to the northeast on the map. There are a few places to grab a bite or a drink near Union South and the big concentration of places is on and near State Street, a pedestrian zone that runs east from Memorial Library (top right). 4 The program 5 NWAV 46 2017 Madison, WI Thursday, November 2nd, 2017 12:00 Registration – 5th Quarter Room, Union South pm-6:00 pm Industry Landmark Northwoods Agriculture 1:00- Progress in regression: Discourse analysis for Sociolinguistics and Texts as data 3:00 Statistical and practical variationists forensic speech sources for improvements to Rbrul science: Knowledge- -

Hyman Lusoga Noun Phrase Tonology PLAR

UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2017) Lusoga Noun Phrase Tonology Larry M. Hyman Department of Linguistics University of California, Berkeley 1. Introduction Bantu tone systems have long been known for their syntagmatic properties, including the ability of a tone to assimilate or shift over long distances. Most systems have a surface binary contrast between H(igh) and L(ow) tone, some also a downstepped H which produces a contrast between H-H and H-ꜜH.1 Given their considerable complexity, much research has focused on the tonal alternations that are produced both lexically and post-lexically. Lusoga, the language under examination in this study, is no exception. Although the closest relative to Luganda, whose tone system has been widely studied (see references in Hyman & Katamba 2010), the only two discussions of Lusoga tonology that I am aware of are Yukawa (2000) and van der Wal (2004:20-30), who outline the surface tone patterns of words in isolation, including certain verb tenses, and illustrate some of the alternations. The latter also points out certain resemblances with Luganda: “Two similarities between Luganda and Lusoga are the clear restriction against LH syllables and the maximum of one H to L pitch drop per word” (van der Wal 2004:29). In this paper I extend the tonal description, with particular attention on the relation between underlying and surface tonal representations. As I have pointed out in a number of studies, two-height tone systems are subject to more than one interpretation: First, the contrast may be either equipolent, H vs. -

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

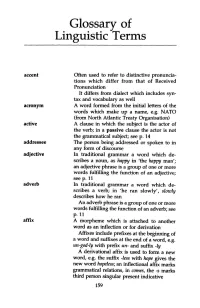

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Predicative Clauses in Today Persian - a Typological Analysis

Asian Social Science; Vol. 11, No. 15; 2015 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Predicative Clauses in Today Persian - A Typological Analysis Pooneh Mostafavi1 1 Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism of Islamic republic of Iran, Tehran, Iran Correspondence: Pooneh Mostafavi, Assistant Professor in General Linguistics, Research Center of linguistics, Inscriptions, and Texts, Research Institute to Iranian Cultural Heritage and Tourism of Islamic republic of Iran, Tehran, Iran. Tel: 98-21-66-736-5867. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 24, 2014 Accepted: February 23, 2015 Online Published: May 15, 2015 doi:10.5539/ass.v11n15p104 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n15p104 Abstract Predicative clauses in world languages encode differently. There are typological researches on this subject in other languages but none of them is on Persian. Stassen in his typological studies shows that the world languages have yielded two strategies for encoding predicative clauses. Copulative and locative/existential constructions are considered as predicative clauses. The strategies which Stassen claims are ‘share’ and ‘split’ strategies. According to Stassen some languages employ one of them and some employ both strategies. He shows in his studies, the language type can be determined by examining the said strategies in them. Using normal data, the present study examines two strategies for today Persian in order to determine its language type. The findings of the present study show that Persian could be categorized in both language types as both strategies are employed by it. Keywords: predicative clauses, copulative construction, locative/existential construction, share strategy, split strategy 1. -

A Parallel Analysis of Have-Type Copular Constructions in Two Have-Less Indo-European Languages

A PARALLEL ANALYSIS OF HAVE-TYPE COPULAR CONSTRUCTIONS IN TWO HAVE-LESS INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES Sebastian Sulger Universitat¨ Konstanz Proceedings of the LFG11 Conference Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2011 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract This paper presents data from two Indo-European languages, Irish and Hindi/ Urdu, which do not use verbs for expressing possession (i.e., they do not have a verb comparable to the English verb have). Both of the languages use cop- ula constructions. Hindi/Urdu combines the copula with either a genitive case marker or a postposition on the possessor noun phrase to construct pos- session. Irish achieves the same effect by combining one of two copula ele- ments with a prepositional phrase. I argue that both languages differentiate between temporary and permanent instances, or stage-level and individual- level predication, of possession. The syntactic means for doing so do not overlap between the two: while Hindi/Urdu employs two distinct markers to differentiate between stage-level and individual-level predication, Irish uses two different copulas. A single parallel LFG analysis for both languages is presented based on the PREDLINK analysis. It is shown how the analysis is capable of serving as input to the semantics, which is modeled using Glue Semantics and which differentiates between stage-level and individual-level predication by means of a situation argument. In particular, it is shown that the inalienable/alienable distinction previ- ously applied to the Hindi/Urdu data is insufficient. The reanalysis presented here in terms of the stage-level vs. individual-level distinction can account for the data from Hindi/Urdu in a more complete way. -

Hungarian Copula Constructions in Dependency Syntax and Parsing

Hungarian copula constructions in dependency syntax and parsing Katalin Ilona Simko´ Veronika Vincze University of Szeged University of Szeged Institute of Informatics Institute of Informatics Department of General Linguistics MTA-SZTE Hungary Research Group on Artificial Intelligence [email protected] Hungary [email protected] Abstract constructions? And if so, how can we deal with cases where the copula is not present in the sur- Copula constructions are problematic in face structure? the syntax of most languages. The paper In this paper, three different answers to these describes three different dependency syn- questions are discussed: the function head analy- tactic methods for handling copula con- sis, where function words, such as the copula, re- structions: function head, content head main the heads of the structures; the content head and complex label analysis. Furthermore, analysis, where the content words, in this case, the we also propose a POS-based approach to nominal part of the predicate, are the heads; and copula detection. We evaluate the impact the complex label analysis, where the copula re- of these approaches in computational pars- mains the head also, but the approach offers a dif- ing, in two parsing experiments for Hun- ferent solution to zero copulas. garian. First, we give a short description of Hungarian copula constructions. Second, the three depen- 1 Introduction dency syntactic frameworks are discussed in more Copula constructions show some special be- detail. Then, we describe two experiments aim- haviour in most human languages. In sentences ing to evaluate these frameworks in computational with copula constructions, the sentence’s predi- linguistics, specifically in dependency parsing for cate is not simply the main verb of the clause, Hungarian, similar to Nivre et al.