Interrogating Possessive Have: a Case Study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

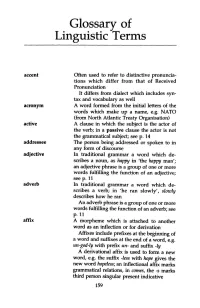

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Periphrastic Causative Constructions in Mehweb Daria Barylnikova National Research University Higher School of Economics

Chapter 6 Periphrastic causative constructions in Mehweb Daria Barylnikova National Research University Higher School of Economics In Mehweb, periphrastic causatives are formed by a combination of the infinitive of the lexical verb with another verb, originally a caused motion verb. Various tests that Mehweb periphrastic causatives do not qualify as fully grammaticalized. But the constructions are not compositional expressions, either. While a clause usually contains either a morphological or a periphrastic causative marker, there are instances where, in a periphrastic causative construction, the lexical verb itself may carry the causative affix, resulting in only one causative meaning. Keywords: causative, periphrastic causative, double causative, Mehweb, Dargwa, East Caucasian. 1 Introduction The causative construction denotes a complex situation consisting of twocom- ponent events: (1) the event that causes another event to happen; and (2) the result of this causation (Comrie 1989: 165–166; Nedjalkov & Silnitsky 1973; Ku- likov 2001). Here, the first event refers to the action of the causer and the second explicates the effect of the causation on the causee. Causativization is a valency-increasing derivation which is applied to the structure of the clause. In the resulting construction, the causer is the subject and the causee shifts to a non-subject position. The set of semantic roles does not remain the same. Minimally, a new agent is added. With a new argument added, we have to redistribute the grammatical relations taking into account how these participants semantically relate to each other. The general scheme of the causative derivation always implies a participant that is treated as a causer (someone or something that spreads their control over the situation and “pulls Daria Barylnikova. -

The Syntax of Simple and Compound Tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko*

Proc Ling Soc Amer Volume 1, Article 18:1-15 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v1i0.3716 The Syntax of simple and compound tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko* Abstract. It is a widely accepted generalization that verbal periphrasis is triggered by in- creased inflectional meaning and a paucity of verbal elements to support its realization. This work examines the limitations on synthetic verbal forms in Ndebele and argues that periphrasis in this language arises via a last-resort grammatical mechanism. The proposed trigger of auxiliary insertion is c-selection – a relation between inflectional categories and verbs. Keywords. verbal periphrasis; default auxiliary; c-selection; Ndebele; Bantu 1. Introduction. This paper focuses on the mechanics of default periphrasis – a phenomenon where a default verb (an auxiliary) appears in a complex inflectional context. I provide an anal- ysis of two types of compound tenses in Ndebele:1 Perfect and Prospective tenses, arguing that periphrastic expressions in those tenses are triggered by c-selectional features on T heads. The type of verbal periphrasis we find in Ndebele is known as the overflow pattern of auxiliary use (Bjorkman, 2011), and is illustrated in (1),2 where Present Perfect and Simple Future are synthetic (there is no auxiliary), but Future Perfect is periphrastic (1-c). (1) Default periphrasis in Ndebele: a. U- ∅- dl -ile Present Perfect/Recent Past (synthetic) 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You have eaten/you ate recently’. b. U- za- dl -a Simple Future (synthetic) 2sg- FUT- eat -FS ‘You will eat’. c. U- za- be u- ∅- dl -ile Future Perfect (periphrastic) 2sg- FUT- aux 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You will have eaten’. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology. -

Chapter 4 Periphrasis and Morphosyntatic Mismatch in Czech

Chapter 4 Periphrasis and morphosyntatic mismatch in Czech Olivier Bonami Université de Paris, Laboratoire de linguistique formelle, CNRS Gert Webelhuth Goethe-Universität Frankfurt a.M. This paper presents an HPSG analysis of the Czech periphrastic past and condi- tional at the morphology-syntax interface. After clarifying the status of Czech aux- iliaries as words rather than affixes, we discuss the fact that the past tense exempli- fies the phenomenon of zero periphrasis, where a form of the main verb normally combined with an auxiliary can stand on its own in some paradigm cells. We ar- gue that this is the periphrastic equivalent of zero exponence, and show how the phenomenon can be accommodated within a general theory of periphrasis, where periphrasis is a particular instance of a mismatch between morphology and syntax. 1 Introduction The term “inflectional periphrasis” denotes a situation where a construction in- volving two or more words stands in paradigmatic opposition with a single word in the expression of a morphosyntactic contrast. The two Czech examples in (1) illustrate this: where the present indicative of čekat is expressed by the single word čekáme in (1a), its past indicative is expressed by the combination of the two words jsme and čekali, as shown in (1b). (1) a. Čekáme na Jardu. wait.prs.1pl for Jarda.acc.sg ‘We are waiting for Jarda.’ Olivier Bonami & Gert Webelhuth. 2021. Periphrasis and morphosyntatic mismatch in Czech. In Berthold Crysmann & Manfred Sailer (eds.), One-to-many relations in morphology, syntax, and semantics, 85–115. Berlin: Language Science Press. DOI: 10. 5281/zenodo.4729795 Olivier Bonami & Gert Webelhuth b. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

*65 EØ RS Mitipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P

1100&*430 ERIC RE PeRT .RESUNE IEO 010 -t-60 1W,29Hib 24 (REV) USSGE IIANUAL:44LANGUAGE CUUICIMUK. I AND !I TEACHER V ER&Iet4, ZHAER4ALURTAWR RaR610280 UNC.VERSITY OE ORE?, -EUGENE Cit9+1*114114411 1111409,40116.C431 . *65 EØ RS MiTipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P. *GRAMM-0..111GhTH- IIRAINEV.- sevens .'GRADEs. vitiCIINUCAILOCSUIDESS *TIEAZINING- SUIDESL 11-YEAL4IVIL 61/10Ett. TiENGLISK EWEN/v; MESONV4-PROJECIr'ENG11314-- RE* GRAM* A IIANUSL, GRINAR- WAGE WAS PRIEN*.f.a *OR- -TEACHINC,1semoffspoi, AND EIGHTIWERMSE- MOMS .CARINECULUNS.- THEP-MANUAt 11111S44R,-TEAT;NERWAIND CONTAINS1 96 ' GRIMMAR_ USAGEWITEett -*WOE 4-1111111), 4ItykiPROF1TSO1Y,-:TRENNIED: .4N SENENTWAID: E IGHTW GRAvegq: THE7COIITEInt-41ave-litst ,i4MIANGEO- ALAINACITICALLY-41101 A GAUt MOM '41F- -CROSSMIEFERENEU,-311EIMINUAL -414--STIODENT 4111.11NADVE_':OP-.4=UNISSORMATI.-4.14AL'IMAPSIAL--Te MEGRIM: -47 NTH SUER- -ALIPECTS 1iI E 1INGUSH 7CURRICARAIMIAN ACCOMPANYING MANUAL WAS ?NEPA-RED FOR -STUOEUT USE :4110,-010 :ant; IMO el OREGON etlittfAcilLatIM 5.xuuY CINTER **0 014 VELEM IL SiDEPARTMENT OFHEMplti: MICATION v-4 Office cif Echkgati On d**filthy has beenreproduced exactlyslitectile Co This document Points Of VieW OrOPielone organizationoriginating It. v-1 person or represent OMNIOff Ice etEducation stated donot necessarily CI position or policy. C) I USAGE ISAIWATe !ammo Curriculum I Mid II Teacher I/onion The project reported hereinwas -supported through the Cooperative ResearchPrograxa of- the Office of Education, U, S. Departgle4totilealt4s Education, and Welfare USAGE MANUAL TABLE OFCONTENTS Etas Abbreviations 1 Bust for burst Accent- Except 3. CapitalCapitol a Adjective 1 Capitalization 9 Adverb 2 Case 10 I Advice- Advise 2 clothsClothes 11 Affect- Effect 3 Colon 11 Agreement 3 Comma 11 Ain't 5 Almost-Most' 5 ConjUnction 11 Already-All ready 5 Contractions 12 All right 5 tOundil- Counsel 12 Altogether - All together 5 toUrse-Coarse 12 Among- Between 6 DetertDessert 12 ft.n-And 6 Determiner 13 Antecedent 6 ed -bove 13 t Apostrophe 6 Done foi-' did 18 Appositive 7 Negative 14 s. -

On the Structure of Negative Statements in Modern English Correspondence

I know not of any reason why I should use do: on the structure of negative statements in modern English correspondence Del ocaso del adverbio not al despertar del auxiliar do: la evolución de las estructuras negativas en inglés moderno Gemma Plaza Tejedor Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Resumen: A lo largo de las últimas décadas han sido Abstract: In the last decades, many research numerosos los estudios lingüísticos centrados en la studies in Linguistics have been focused on the history historia de la lengua inglesa, cobrando especial impor- of the English language; in this field, corpora analyses tancia los análisis de corpus, ya que estos ofrecen un have become increasingly important since they provide acceso rápido a datos lingüísticos reales. La idea prin- easy access to actual linguistic data. The main purpose cipal de este estudio es analizar la evolución de las of this study is to describe the evolution of the different diferentes estructuras gramaticales usadas para formar grammatical structures used in negative statements in la negación en Inglés Moderno –que abarca de 1500 Modern English –which spans from 1500 to 1900, hasta 1900 aproximadamente– teniendo como objeto de approximately–, by analysing public and private cor- estudio cartas públicas y privadas escritas entre los respondence written between the 16th and the 19th cen- siglos XVI y XIX recopiladas en los diferentes corpus turies and included in the corpora selected for this aquí incluidos. Los datos extraídos de estos corpus study. The data -

PREPOSITIONAL SYSTEMS in BIBLICAL GREEK, GOTHIC, CLASSICAL ARMENIAN, and OLD CHURCH SLAVIC by OLGA THOMASON (Under the Direction

PREPOSITIONAL SYSTEMS IN BIBLICAL GREEK, GOTHIC, CLASSICAL ARMENIAN, AND OLD CHURCH SLAVIC by OLGA THOMASON (Under the Direction of Jared Klein) ABSTRACT This study investigates the systems of prepositions in Biblical Greek, Gothic, Classical Armenian and Old Church Slavic based on data collected from the New Testament text of the canonical Gospels in each language. The first part of the study focuses on the inventory of prepositions in each of the languages mentioned. It provides an exhaustive overview of the prepositional systems examining the division of semantic space in them. The second part of this investigation is a comparative study of the overall systems of prepositions in all four languages. It observes similarities and differences between prepositional systems examined in the first part. The prepositional systems of the languages mentioned have approximately the same range of semantic functions. Each system includes proper and improper prepositional phrases that regularly alternate with each other as well as with nominal ones. The semantics of most prepositions in each of the languages under consideration are closely connected with spatial notions. This is especially common for improper prepositions. Although it is customary for a proper prepositional phrase to be dominant in a certain semantic field, we find instances in all four languages where a construction with an improper preposition prevails. Numerous notions are expressed by a variety of phrases, but there are instances where a concept is indicated only by one construction. The comparative analysis of the translations of the New Testament from Biblical Greek into Gothic, Classical Armenian, and Old Church Slavic shows that there are no absolute prepositional equivalents in these languages, but different types of correspondences can be established.