Fundamentals of English Syntax 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

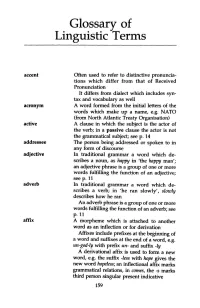

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

Interrogating Possessive Have: a Case Study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó

99 József Andor: Interrogating possessive have: a case study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó József Andor Interrogating possessive have: a case study Abstract Major, standard grammars of English give an account and interpret interrogatively used possessive have as a unique specialty of genres and text types of British English. Reviewing descriptions offered by some of these grammars and presenting empirically based evidence on acceptability of usage and function, the present paper offers results revealing the occurrence of inverted possessive have in other regional varieties, specifically in American English. It is suggested that have, retaining its possessive lexical meaning behaves as a semi-auxiliary in such constructions. Keywords: possessive, inversion, do-support, corpus-based, semi-auxiliary, notionally and morpho-syntactically based categorization 1 Introduction What made me start researching the functional-semantic and pragmatic-contextual force of interrogative sentences with the possessive lexical status of have was finding the example Have you a pen? on page 88 of the recently published Oxford Modern English Grammar authored by Bas Aarts (2011). The sentence was given under section 4.1.1.6. titled “Subjects invert positions with verbs in interrogative main clauses”, which section, due to its scope, did not address discussing syntactic variation concerning possessive usage of have, contrasting syntactic as well as cognitive-semantic and pragmatic, usage based issues of formally pure cases of inversion with the co-occurrence of have and do-support (also called do-periphrasis) or the have got construction. This came to me as a surprise, as types of have-based possession could have been discussed in a dictionary based on one of the most valuable corpora of British English, the British component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB). -

*65 EØ RS Mitipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P

1100&*430 ERIC RE PeRT .RESUNE IEO 010 -t-60 1W,29Hib 24 (REV) USSGE IIANUAL:44LANGUAGE CUUICIMUK. I AND !I TEACHER V ER&Iet4, ZHAER4ALURTAWR RaR610280 UNC.VERSITY OE ORE?, -EUGENE Cit9+1*114114411 1111409,40116.C431 . *65 EØ RS MiTipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P. *GRAMM-0..111GhTH- IIRAINEV.- sevens .'GRADEs. vitiCIINUCAILOCSUIDESS *TIEAZINING- SUIDESL 11-YEAL4IVIL 61/10Ett. TiENGLISK EWEN/v; MESONV4-PROJECIr'ENG11314-- RE* GRAM* A IIANUSL, GRINAR- WAGE WAS PRIEN*.f.a *OR- -TEACHINC,1semoffspoi, AND EIGHTIWERMSE- MOMS .CARINECULUNS.- THEP-MANUAt 11111S44R,-TEAT;NERWAIND CONTAINS1 96 ' GRIMMAR_ USAGEWITEett -*WOE 4-1111111), 4ItykiPROF1TSO1Y,-:TRENNIED: .4N SENENTWAID: E IGHTW GRAvegq: THE7COIITEInt-41ave-litst ,i4MIANGEO- ALAINACITICALLY-41101 A GAUt MOM '41F- -CROSSMIEFERENEU,-311EIMINUAL -414--STIODENT 4111.11NADVE_':OP-.4=UNISSORMATI.-4.14AL'IMAPSIAL--Te MEGRIM: -47 NTH SUER- -ALIPECTS 1iI E 1INGUSH 7CURRICARAIMIAN ACCOMPANYING MANUAL WAS ?NEPA-RED FOR -STUOEUT USE :4110,-010 :ant; IMO el OREGON etlittfAcilLatIM 5.xuuY CINTER **0 014 VELEM IL SiDEPARTMENT OFHEMplti: MICATION v-4 Office cif Echkgati On d**filthy has beenreproduced exactlyslitectile Co This document Points Of VieW OrOPielone organizationoriginating It. v-1 person or represent OMNIOff Ice etEducation stated donot necessarily CI position or policy. C) I USAGE ISAIWATe !ammo Curriculum I Mid II Teacher I/onion The project reported hereinwas -supported through the Cooperative ResearchPrograxa of- the Office of Education, U, S. Departgle4totilealt4s Education, and Welfare USAGE MANUAL TABLE OFCONTENTS Etas Abbreviations 1 Bust for burst Accent- Except 3. CapitalCapitol a Adjective 1 Capitalization 9 Adverb 2 Case 10 I Advice- Advise 2 clothsClothes 11 Affect- Effect 3 Colon 11 Agreement 3 Comma 11 Ain't 5 Almost-Most' 5 ConjUnction 11 Already-All ready 5 Contractions 12 All right 5 tOundil- Counsel 12 Altogether - All together 5 toUrse-Coarse 12 Among- Between 6 DetertDessert 12 ft.n-And 6 Determiner 13 Antecedent 6 ed -bove 13 t Apostrophe 6 Done foi-' did 18 Appositive 7 Negative 14 s. -

Features of Lexical Verbs in the Discussion Section of Masters' Dissertations

FEATURES OF LEXICAL VERBS IN THE DISCUSSION SECTION OF MASTERS' DISSERTATIONS FAIZAH BINTI MOHAMAD NUSRI FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2018 FEATURES OF LEXICAL VERBS IN THE DISCUSSION SECTION OF MASTERS' DISSERTATIONS FAIZAH BINTI MOHAMAD NUSRI DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGLISH AS SECOND LANGUAGE FACULTY OF LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2018 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Faizah binti Mohamad Nusri I.C/Passport No: 860610-38-6394 Matric No: TGB 120045 Name of Degree: Master of English as Second Language Title of Project Paper/Research Report/Dissertation/Thesis (“this Work”): Features of Lexical Verbs in the Discussion Section of Masters’ Dissertations Field of Study: Corpus Linguistics I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of making this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

Department of English and American Studies Phrasal Verbs in the British National Corpus and ELT Textbooks 2018

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Jan Štěrba Phrasal Verbs in the British National Corpus and ELT Textbooks Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. František Tůma, Ph. D. 2018 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Jan Štěrba I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. František Tůma, Ph.D., for his time, kindness, willingness to help and the excellent feedback he provided me with. I would also like to thank my original supervisor, doc, PhDr. Naděžda Kudrnáčová, Csc., who approached Mr. Tůma after my topic had to be changed and thus helped me to finish the thesis successfully. I cannot forget to thank James for proofreading the whole thesis as well as my grandfather who proofread the Czech parts. I am also very grateful for the support I have received from my family throughout my studies and finally, I have to thank my girlfriend Janča for simply being out there for me. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 9 1. Multi-word Verbs ....................................................................................................... 13 1.1. Phrasal Verbs ....................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1. Definition ...................................................................................................... -

Chapter 36. Grammatical Change

Chapter 36. Grammatical change Willem B. Hollmann 36.1 Preliminaries Grammatical change is an extremely interesting area but does presuppose some knowledge of grammar. For this reason, if you do not have this knowledge yet, this chapter will work best if you have first familiarised yourself with the terminology discussed in the chapters on grammar, i.e. especially chapters and 5–8. Chapters on grammatical change in traditional textbooks on the history of English or historical linguistics by and large focus on change in morphology (the structure of words) and/or syntax (the structure of phrases and clauses). Some of the most important changes in the history of English can indeed be described in more or less purely structural terms, i.e. without considering meaning very much. Sentences (1–2), below, illustrate object-verb (or OV) constituent order,1 which was quite frequent in Old English but became less and less common during Middle English, until it was completely lost in the sixteenth century. (1) Gregorius [hine object] [afligde verb]. (Homilies of Ælfric 22.624) Gregory him put-to-flight ‘Gregory made him flee’ (2) Ne sceal he [naht unaliefedes object] [don verb]. (Pastoral Care 10.61.14) not shall he nothing unlawful do ‘He will do nothing unlawful’ Example (2) shows that we must be careful when discussing OV order in Old and Middle English: the finite verb (here: sceal) actually often occurred before the object, taking up the second position in the clause (the initial position here being occupied by the negator ne). Thus, it is often only the lexical verb (here: don) that follows the object. -

Phrasal Verbs in Learner English: a Corpus-Based Study of Lithuanian

PHRASAL VERBS IN LEARNER ENGLISH: A CORPUS-BASED STUDY OF LITHUANIAN .. Božena Garbatovič, Jonė Grigaliūnienė Baltic Journal of English Language, Literature and Culture Vol. 10, 2020: 36–53 https://doi.org/10.22364/BJELLC.10.2020.03 PHRASAL VERBS IN LEARNER ENGLISH: A CORPUS-BASED STUDY OF LITHUANIAN AND POLISH LEARNERS OF ENGLISH BOŽENA GARBATOVIČ AND JONĖ GRIGALIŪNIENĖ Vilnius University, Lithuania Abstract. Phrasal verbs, though very common in the English language, are acknowledged as difficult to acquire by non-native learners of English. The present study examines this issue focusing on two learner groups from different mother tongue backgrounds, i.e. Lithuanian and Polish advanced students of English. The analysis is conducted based on Granger’s (1996) Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis methodology, investigating the Lithuanian and Polish components of the International Corpus of Learner English, as well as the Louvain Corpus of Native English Essays. The results obtained in the study prove that both learner groups underuse phrasal verbs compared with native English speakers. It is concluded that this could be due to the learners’ limited repertoire of phrasal verbs as they employ significantly fewer phrasal- verb types than native speakers. Furthermore, it is noticed that learners face similar stylistic, semantic and syntactic difficulties in the use of this language feature. In particular, the analysis shows that such errors might be caused by native language interference, as well as the inherent complexity of phrasal verbs. The present study not only helps to account for the challenges that are common to those language groups which lack phrasal verbs in their linguistic repository, but also provides insights into the understanding of advanced learner language. -

Chapter 2 from Elly Van Geldern 2017 Minimalism Building Blocks This

Chapter 2 From Elly van Geldern 2017 Minimalism Building blocks This chapter reviews the lexical and grammatical categories of English and provides criteria on how to decide whether a word is, for example, a noun or an adjective or a demonstrative. This knowledge of categories, also known as parts of speech, can then be applied to languages other than English. The chapter also examines pronouns, which have grammatical content but may function like nouns, and looks at how categories change. Categories continue to be much discussed. Some linguists argue that the mental lexicon lists no categories, just roots without categorial information, and that morphological markers (e.g. –ion, -en, and zero) make roots into categories. I will assume there are categories of two kinds, lexical and grammatical. This distinction between lexical and grammatical is relevant to a number of phenomena that are listed in Table 2.1. For instance, lexical categories are learned early, can be translated easily, and be borrowed because they have real meaning; grammatical categories do not have lexical meaning, are rarely borrowed, and may lack stress. Switching between languages (code switching) is easier for lexical than for grammatical categories. Lexical Grammatical First Language Acquisition starts with lexical Borrowed grammatical categories are rare: categories, e.g. Mommy eat. the prepositions per, via, and plus are the rare borrowings. Lexical categories can be translated into another language easily. Grammatical categories contract and may lack stress, e.g. He’s going for he is going. Borrowed words are mainly lexical, e.g. taco, sudoko, Zeitgeist. Code switching between grammatical categories is hard: Code switching occurs: I saw adelaars *Ik am talking to the neighbors. -

Copular Verbs of the Become Type and the Expression of ‘Resulting’ Meaning in English and in Czech: a Contrastive Corpus-Supported View

2013 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 99–115 PHILOLOGICA 3 / PRAGUE STUDIES IN ENGLISH XXVI COPULAR VERBS OF THE BECOME TYPE AND THE EXPRESSION OF ‘RESULTING’ MEANING IN ENGLISH AND IN CZECH: A CONTRASTIVE CORPUS-SUPPORTED VIEW MARKÉTA MALÁ 1. Copular clauses in English and in Czech Copular clauses, i.e. clauses with a verbo-nominal predicate, are used both in English and in Czech as a means of ascribing a quality, property or value to the subject. How- ever, the repertoires of copular verbs available in the two languages differ significantly. In Czech, it is only the copula být (‘be ’ ) that is generally considered a linking verb, with some grammars also accepting its resulting counterpart stát se (‘become ’ ) as a member of the class. In English, a range of copular verbs covers the ascription of a ‘current ’ qual- ity (verbs of ‘remaining ’ , sensory perception, or epistemic modification) as well as the expression of the resultant state. We shall focus on the latter group, considering a) how the various types of ‘becoming ’ differ from one another in English, b) how these differ- ences are rendered in the Czech translation, and c) what the Czech counterparts can suggest about the ways of expressing ‘resulting ’ meaning in English. 2. The method and material The method can be described as a bidirectional corpus-supported1 approach. The analysis (see Figure 1) proceeds from a grammatical and semantic description of the English resulting copular verbs in English original texts (step one) to a study of their patterns of translation correspondence in Czech (step two). It can be assumed that for- mally distinct constructions which share the same function or meaning will also share the same translation counterparts.