The Verb Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

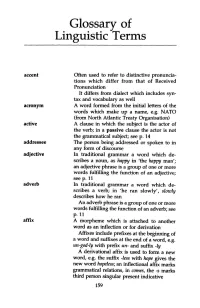

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Mathias Jenny: the Verb System of Mon

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2005 The verb system of Mon Jenny, Mathias Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-110202 Dissertation Originally published at: Jenny, Mathias. The verb system of Mon. 2005, University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts. Mathias Jenny: The Verb System of Mon Contents Preface v Abbreviations viii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 The Mon people and language 1 1.2 Sources and methodology 8 1.3 Sentence structure 13 1.4 Sentence types 15 1.4.1 Interrogative sentences 15 1.4.2 Imperative sentences 18 1.4.3 Conditional clauses 20 1.5 Phonology of Mon 23 1.5.1 Historical overview 23 1.5.2 From Middle Mon to Modern Mon 26 1.5.3 Modern dialects 30 1.5.4 The phonology of SM 33 1.5.5 Phonology and the writing system 37 2. Verbs in Mon 42 2.1 What are verbs? 42 2.2 The predicate in Mon 43 2.2.1 Previous studies of the verb in Mon 44 2.2.2 Verbs as word class in Mon 47 2.2.3 Nominal predicates and topicalised verbs 49 2.3 Negation 51 2.3.1 Negated statements and questions 51 2.3.2 Prohibitive 58 2.3.3 Summary 59 2.4 Verbal morphology 60 2.4.1 Historical development 60 2.4.2 Modern Mon 65 2.4.3 Summary 67 2.5 Verb classes and types of verbs 67 2.5.1 Transitive and intransitive verbs 68 2.5.2 Aktionsarten 71 2.5.3 Resultative verb compounds (RVC) 75 2.5.4 Existential verbs (Copulas) 77 2.5.4.1 ‹dah› th ‘be something’ 78 2.5.4.2 ‹måï› mŋ ‘be at, stay’ 80 2.5.4.3 ‹nwaÿ› nùm ‘be at, exist, have’ 82 2.5.4.4 ‹(hwa’) seï› (hùʔ) siəŋ ‘(not to) be so’ 86 i Mathias Jenny: The Verb System of Mon 2.5.5 Directionals 88 2.6 Complements of verbs 89 2.6.1 Direct objects 90 2.6.2 Oblique objects 91 2.6.3 Complement clauses 95 3. -

Ter + Past Participle Or Estar + Gerund? Aspect and Syntactic Variation in Brazilian Portuguese

Ter + past participle or Estar + gerund? Aspect and Syntactic Variation in Brazilian Portuguese Ronald Beline Mendes University of São Paulo The verbal aspect in Brazilian Portuguese (BP) has been described by a number of authors. Wachowicz 2003, based on Verkuyl 1993 and 1999, has accounted for the iterative and progressive interpretations of estar (be) + gerund. Ilari 2000 shows why ter (have) + participle is recognized as the iterative periphrasis in that language, even though it can possibly express progressive, durative meanings. Castilho 2000 proposes an aspectual typology for the aspect and shows how periphrastic constructions are productive in BP aspectual composition. None of those authors have, however, approached the use of those periphrases from a variationist, quantitative perspective. In contemporary BP, estar + gerund and ter + participle actually appear in the same context when the aspectual interpretation is iterative, and are commonly found in the data provided by a same speaker. That is a synchronic evidence of their variable use, as shown below: (1) Eu estou estudando muito ultimamente. I am studying much lately "I have been studying a lot lately" (iterative) (2) Eu tenho estudado muito ultimamente. I have studied much lately "I have been studying a lot lately" (iterative) Diachronic data show that their uses changed. In the 16th century, neither of the periphrases were used to express iterative - estar + gerund could only express durative, progressive meanings, whereas ter + participle would convey a resultative, punctual meaning, as in (3) and (4) respectively. In the 17th and 18th centuries, some tokens of ter + participle are found to be ambiguous, the iterative and resultative being possible. -

Mandarin Resultative Constructions and Aspect Incorporation Chienjer Lin University of Arizona

Aspect is Result: Mandarin Resultative Constructions and Aspect Incorporation Chienjer Lin University of Arizona 0 Introduction Aspect and resultative constructions have been treated as distinct phenomena in the linguistic literature. Viewpoint aspect encodes ways of viewing the “internal temporal constituency of a situation;” in particular, it provides information about completion and boundedness that is superimposed on verb phrases (Comrie 1976:3). It takes place at a functional position above the verb phrase. A sentence with simple past tense like (1) describes an action that occurred prior to the speech time. The perfective aspect phrase have V in (2) emphasizes the completion and experience of this action. Aspect is therefore seen as additional information that modifies the telicity of a verb phrase. (1) I saw him in the park. (2) I have seen him in the park twice. Resultatives on the other hand are taken as information within the verb phrase. They typically involve at least two events—a causative event followed by a resultative state, which is denoted by a small clause embedded under the main verb (Hoekstra 1989). For instance, the verb phrase wipe the slate clean involves the action of wiping and the final state of the slate’s being clean. The resultative state is embedded under the verb phrase, governed by the causative verb head. This paper explores the possibility of an alternative account for viewpoint aspect. Instead of viewing aspect as a functional head above verb phrases, I attempt to associate aspect with resultative predicates and claim that (at least part of) aspect should be base generated below the verb phrases like resultatives. -

Building Resultatives Angelika Kratzer, University of Massachusetts at Amherst August 20041

1 Building Resultatives Angelika Kratzer, University of Massachusetts at Amherst August 20041 1. The construction: Adjectival resultatives Some natural languages allow their speakers to put together a verb and an adjective to create complex predicates that are commonly referred to as “resultatives”. Here are two run-of-the- mill examples from German2: (1) Die Teekanne leer trinken The teapot empty drink ‘To drink the teapot empty’ (2) Die Tulpen platt giessen The tulips flat water Water the tulips flat Resultatives raise important questions for the syntax-semantics interface, and this is why they have occupied a prominent place in recent linguistic theorizing. What is it that makes this construction so interesting? Resultatives are submitted to a cluster of not obviously related constraints, and this fact calls out for explanation. There are tough constraints for the verb, for example: 1 . To appear in Claudia Maienborn und Angelika Wöllstein-Leisten (eds.): Event Arguments in Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse. Tübingen, Niemeyer. Thank you to Claudia Maienborn and Angelika Wöllstein-Leisten for organizing the stimulating DGfS workshop where this paper was presented, and for waiting so patiently for its final write-up. Claudia Maienborn also sent comments on an earlier version of the paper, which were highly appreciated. 2 . (2) is modeled after a famous example in Carrier & Randall (1992). 2 (3) a. Er hat seine Familie magenkrank gekocht. He has his family stomach sick cooked. ‘He cooked his family stomach sick.’ b. * Er hat seine Familie magenkrank bekocht. He has his family stomach sick cooked-for And there are also well-known restrictions for the participating adjectives (Simpson 1983, Smith 1983, Fabb 1984, Carrier and Randall 1992): (4) a. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

Types of Predicate

chapter 9 Types of Predicate This chapter deals with the types of predicates. The predicate of a sentence can be expressed by almost any word classes, not only through a verb. How- ever, verbal predicates are most common, about 87% of all predicates are verbs. They can be simple, containing only one verb or complex with more than one verbal element. The following figure shows the occurrence of predicates in an annotated sub-corpus. In the following sections, first the verbal predicates are discussed. 1 Verbal Predication The most common distinction between verbal predicates is their simplicity. The verbal predicate usually is simple. Complex predicates consist of an aux- iliary and a lexical verb. There are only few auxiliary verbs, one of these aux- iliaries is the negation auxiliary, which serves to form standard negation and appears most often in complex verbal predicates. Other auxiliaries are seman- tically not empty, but they have an additional, mostly modal meaning. In this section, only examples for the usage of auxiliary konɨďi ‘go away’ are given. For a detailed description of auxiliaries see Section 3.3 in Chapter 3, for negation see Chapter 12. The auxiliary verb konɨďi ‘go away’ appears only in essive or resultative- translative constructions. In these constructions an NP is followed by the infini- tive form (converb1) of the BE-verb (isʲa) and the conjugated form of the aux- iliary. Word order variations are not allowed. Contrary to Enets and Nenets, the infinitive/converb construction wasn’t grammaticalized as the essive case. This form has word stress of its own, and it never undergoes cliticization.