The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

Tense, Time, Aspect and the Ancient Greek Verb by Jerome Moran

Tense, Time, Aspect and the Ancient Greek Verb by Jerome Moran early every – no, every – Greek The questions in the first sentence 3. In Greek the tense of a verb may Ngrammar and course book, even (‘deliberative’ questions, therefore in denote something different from or the most comprehensive (in English, the subjunctive) refer to present (or additional to the time at which the at any rate), gives a very skimpy, perhaps future) time. But one of act, event, occurrence, process, state perfunctory and unhelpful account — the verbs (εἴπωμεν) is in a past denoted by the verb is located. In insofar as it gives any account at all – of tense (aorist). The second sentence particular, it may denote something what ‘aspect’ is and how exactly it is refers to past time, but one of the called ‘aspect’. related to verb tense and time (which verbs (βούλοιτο) is in the present tend to be conflated). Most of the tense. 4. Whether the tense of a Greek verb books and articles on the subject of denotes time or/and aspect depends the aspect of the Greek verb are What is going on? The answer is in the first place on the mood of the accessible only to the professional something called ‘aspect’, and its verb (‘the form which a verb philologist, and can’t therefore be connection with tense and time. Just assumes in order to reflect the easily applied by non-specialists to the note for now a difference in the manner (modus) in which the speaker understanding of the actual usage of kind of things denoted by the verbs conceives the action’ (Woodcock)). -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

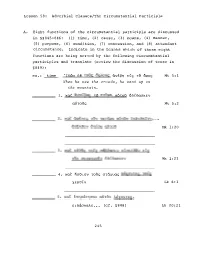

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Mathias Jenny: the Verb System of Mon

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2005 The verb system of Mon Jenny, Mathias Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-110202 Dissertation Originally published at: Jenny, Mathias. The verb system of Mon. 2005, University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts. Mathias Jenny: The Verb System of Mon Contents Preface v Abbreviations viii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 The Mon people and language 1 1.2 Sources and methodology 8 1.3 Sentence structure 13 1.4 Sentence types 15 1.4.1 Interrogative sentences 15 1.4.2 Imperative sentences 18 1.4.3 Conditional clauses 20 1.5 Phonology of Mon 23 1.5.1 Historical overview 23 1.5.2 From Middle Mon to Modern Mon 26 1.5.3 Modern dialects 30 1.5.4 The phonology of SM 33 1.5.5 Phonology and the writing system 37 2. Verbs in Mon 42 2.1 What are verbs? 42 2.2 The predicate in Mon 43 2.2.1 Previous studies of the verb in Mon 44 2.2.2 Verbs as word class in Mon 47 2.2.3 Nominal predicates and topicalised verbs 49 2.3 Negation 51 2.3.1 Negated statements and questions 51 2.3.2 Prohibitive 58 2.3.3 Summary 59 2.4 Verbal morphology 60 2.4.1 Historical development 60 2.4.2 Modern Mon 65 2.4.3 Summary 67 2.5 Verb classes and types of verbs 67 2.5.1 Transitive and intransitive verbs 68 2.5.2 Aktionsarten 71 2.5.3 Resultative verb compounds (RVC) 75 2.5.4 Existential verbs (Copulas) 77 2.5.4.1 ‹dah› th ‘be something’ 78 2.5.4.2 ‹måï› mŋ ‘be at, stay’ 80 2.5.4.3 ‹nwaÿ› nùm ‘be at, exist, have’ 82 2.5.4.4 ‹(hwa’) seï› (hùʔ) siəŋ ‘(not to) be so’ 86 i Mathias Jenny: The Verb System of Mon 2.5.5 Directionals 88 2.6 Complements of verbs 89 2.6.1 Direct objects 90 2.6.2 Oblique objects 91 2.6.3 Complement clauses 95 3. -

The Indo-European K-Aorist

Frederik Kortlandt, Leiden University, www.kortlandt.nl The Indo-European k-aorist Ten years ago I wrote (2007: 155f.): “It has been impossible to establish an original meaning for the alleged velar suffix in the root aorists fēcī and iēcī (cf. Untermann 1993). I therefore think that we have to look for a phonetic explanation. Since the -k- is limited to the singular in the Greek active aorist indicative, I am h inclined to regard fēc- as the phonetic reflex of monosyllabic *dhēk < *d eH1t, where *-k- may have been either an intrusive consonant after the laryngeal before the final *-t, like -p- in Latin emptus ‘bought’ or *-s- in Hittite ezta ‘he ate’ < *edto, or a remnant of the Indo-Uralic velar consonant from which the laryngeal developed, as in Finnish teke- ‘make’ (cf. Kortlandt 2002: 220). The present stems of faciō and iaciō support the former possibility. This would also account for Tocharian A tāk, B tāka ‘became’, h h which reflect *steH2t. In a similar vein I reconstruct *hēp < *g eH1b t and *sēp < *seH1pt for Oscan hipid, hipust ‘will hold’, sipus ‘knowing’. While Oscan hafiest ‘will hold’ is in accordance with the Latin, Celtic and Germanic evidence, Umbrian hab- suggests that h h h *g eH1b - yielded *g eb- with preglottalized *-b- at an early stage and that this root- final consonant was generalized in Italic. It appears that Latin capiō ‘take’ < *kH2p- adopted the -ē- of cēpī from its synonym apiō, ēpī, and that scabō, scābī ‘scratch’ reflects original *skebh- (cf. Schrijver 1991: 431).” As Untermann observes (1993: 463), the Latin stems fac- and iac- behave as roots of primary verbs, and the same holds for Sabellic and Venetic. -

Ter + Past Participle Or Estar + Gerund? Aspect and Syntactic Variation in Brazilian Portuguese

Ter + past participle or Estar + gerund? Aspect and Syntactic Variation in Brazilian Portuguese Ronald Beline Mendes University of São Paulo The verbal aspect in Brazilian Portuguese (BP) has been described by a number of authors. Wachowicz 2003, based on Verkuyl 1993 and 1999, has accounted for the iterative and progressive interpretations of estar (be) + gerund. Ilari 2000 shows why ter (have) + participle is recognized as the iterative periphrasis in that language, even though it can possibly express progressive, durative meanings. Castilho 2000 proposes an aspectual typology for the aspect and shows how periphrastic constructions are productive in BP aspectual composition. None of those authors have, however, approached the use of those periphrases from a variationist, quantitative perspective. In contemporary BP, estar + gerund and ter + participle actually appear in the same context when the aspectual interpretation is iterative, and are commonly found in the data provided by a same speaker. That is a synchronic evidence of their variable use, as shown below: (1) Eu estou estudando muito ultimamente. I am studying much lately "I have been studying a lot lately" (iterative) (2) Eu tenho estudado muito ultimamente. I have studied much lately "I have been studying a lot lately" (iterative) Diachronic data show that their uses changed. In the 16th century, neither of the periphrases were used to express iterative - estar + gerund could only express durative, progressive meanings, whereas ter + participle would convey a resultative, punctual meaning, as in (3) and (4) respectively. In the 17th and 18th centuries, some tokens of ter + participle are found to be ambiguous, the iterative and resultative being possible. -

Tense and Aspect (Sentences)

Tense and Aspect Tense or Aspect: A quick-reference table Form How it behaves Indicative Always by tense Infinitive Naturally by aspect (after e.g. βούλομαι) but In Indirect Statements/Commands, it behaves like what it replaces Optative Naturally by aspect (e.g. after ἵνα, in Indefinite Clauses/Conditions) but In Indirect Statements/Questions, it behaves like what it replaces Subjunctive Always by aspect Imperative Always by aspect It is clear from the above table that most verb forms in Greek, including nearly everything that you find in subordinate clauses, is more likely to behave by aspect than by tense. NB The Imperfect and Future (where these exist) always operate by tense. Practice Sentences 1. οἱ δ᾽ Ἀθηναῖοι, ἵνα μὴ διασπασθείησαν, ἐπηκολούθουν. ..................................................................................................................................... 2. οὕτω δ᾽ ἐτάχθησαν, ἵνα μὴ διέκπλουν διδοῖεν. ..................................................................................................................................... 3. ὑπονοῶν ὅτι ἀποπορεύσοιτο καὶ ἀπάξοι τὸν στρατὸν οἴκαδε, διέβη τῆς νυκτὸς. ..................................................................................................................................... 4. οἴμοι, τί δράσω; τίς σε βαστάσει φίλων; ..................................................................................................................................... 5. ἐπεὶ δὲ οἱ πολέμιοι κατεῖχον, οὐδὲν ἔχοντες ὅ τι ποιήσαιεν, παρέδοσαν σφᾶς αὐτούς. .................................................................................................................................... -

Greek Tenses in John's Apocalypse

CHAPTER 13 Greek Tenses in John’s Apocalypse: Issues in Verbal Aspect, Discourse Analysis, and Diachronic Change Buist M. Fanning This essay will concentrate on discourse functions for the Greek tenses in the Apocalypse of John. I will pursue this through a dialogue with and critique of David Mathewson’s views as presented in his 2010 monograph published by Brill and an earlier article in Novum Testamentum (2008) on this topic.1 Mathewson’s work is a reflection of a larger school of thought on nt Greek ver- bal usage that has been influenced greatly by Stanley Porter, and so this gives me an opportunity to interact with the views of a larger group of recent writers based on work that I have done on verbal aspect in nt Greek.2 The issue that triggers this discussion is what some have called the confu- sion of tenses or erratic shifting of tenses in John’s Apocalypse, just one area of the larger topic of John’s solecisms or unusual Greek grammatical expressions.3 What Mathewson argues for (following Porter) and what I will dispute in this paper is twofold: (1) that aspect alone is the focus of the ancient Greek tense forms; they do not in themselves express any temporal meaning; in regard to the Apocalypse if we take time out of the equation, we eliminate all of the supposed problems with shifting tense forms; (2) the main secondary effect of aspect is a certain function to reflect discourse prominence, that is, back- ground, foreground, and frontground events or features in a text.