A Discourse Analysis of the Periphrastic Imperfect In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

Aktionsart and Aspect in Qiang

The 2005 International Course and Conference on RRG, Academia Sinica, Taipei, June 26-30 AKTIONSART AND ASPECT IN QIANG Huang Chenglong Institute of Ethnology & Anthropology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Qiang language reflects a basic Aktionsart dichotomy in the classification of stative and active verbs, the form of verbs directly reflects the elements of the lexical decomposition. Generally, State or activity is the basic form of the verb, which becomes an achievement or accomplishment when it takes a directional prefix, and becomes a causative achievement or causative accomplishment when it takes the causative suffix. It shows that grammatical aspect and Aktionsart seem to play much of a systematic role. Semantically, on the one hand, there is a clear-cut boundary between states and activities, but morphologically, however, there is no distinction between them. Both of them take the same marking to encode lexical aspect (Aktionsart), and grammatical aspect does not entirely correspond with lexical aspect. 1.0. Introduction The Ronghong variety of Qiang is spoken in Yadu Township (雅都鄉), Mao County (茂縣), Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (阿壩藏族羌族自治州), Sichuan Province (四川省), China. It has more than 3,000 speakers. The Ronghong variety of Qiang belongs to the Yadu subdialect (雅都土語) of the Northern dialect of Qiang (羌語北部方言). It is mutually intelligible with other subdialects within the Northern dialect, but mutually unintelligible with other subdialects within the Southern dialect. In this paper we use Aktionsart and lexical decomposition, as developed by Van Valin and LaPolla (1997, Ch. 3 and Ch. 4), to discuss lexical aspect, grammatical aspect and the relationship between them in Qiang. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

An Introduction to Dena'ina Grammar

AN INTRODUCTION TO DENA’INA GRAMMAR: THE KENAI (OUTER INLET) DIALECT by Alan Boraas, Ph.D. Professor of Anthropology Kenai Peninsula College Based on reference material by: Peter Kalifornsky James Kari, Ph.D. and Joan Tenenbaum, Ph.D. June 30, 2009 revisions May 22, 2010 Page ii Dedication This grammar guide is dedicated to the 20th century children who had their mouth’s washed out with soap or were beaten in the Kenai Territorial School for speaking Dena’ina. And to Peter Kalifornsky, one of those children, who gave his time, knowledge, and friendship so others might learn. Acknowledgement The information in this introductory grammar is based on the sources cited in the “References” section but particularly on James Kari’s draft of Dena’ina Verb Dictionary and Joan Tenenbaum’s 1978 Morphology and Semantics of the Tanaina Verb. Many of the examples are taken directly from these documents but modified to fit the Kenai or Outer Inlet dialect. All of the stem set and verb theme information is from James Kari’s electronic Dena’ina verb dictionary draft. Students should consult the originals for more in-depth descriptions or to resolve difficult constructions. In addition much of the material in this document was initially developed in various language learning documents developed by me, many in collaboration with Peter Kalifornsky or Donita Peter for classes taught at Kenai Peninsula College or the Kenaitze Indian Tribe between 1988 and 2006, and this document represents a recent installment of a progressively more complete grammar. Anyone interested in Dena’ina language and culture owes a huge debt of gratitude to Dr. -

The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect Version 1.0 July 2007 Joshua T. Katz Princeton University Abstract: The origin of the pluperfect is the biggest remaining hole in our understanding of the Ancient Greek verbal system. This paper provides a novel unitary account of all four morphological types— alphathematic, athematic, thematic, and the anomalous Homeric form 3sg. ᾔδη (ēídē) ‘knew’—beginning with a “Jasanoff-type” reconstruction in Proto-Indo-European, an “imperfect of the perfect.” © Joshua T. Katz. [email protected] 2 The following paper has had a long history (see the first footnote). This version, which was composed as such in the first half of 2006, will be appearing in more or less the present form in volume 46 of the Viennese journal Die Sprache. It is dedicated with affection and respect to the great Indo-Europeanist Jay Jasanoff, who turned 65 in June 2007. *** for Jay Jasanoff on his 65th birthday The Oxford English Dictionary defines the rather sad word has-been as “One that has been but is no longer: a person or thing whose career or efficiency belongs to the past, or whose best days are over.” In view of my subject, I may perhaps be allowed to speculate on the meaning of the putative noun *had-been (as in, He’s not just a has-been; he’s a had-been!), surely an even sadder concept, did it but exist. When I first became interested in the Indo- European verb, thanks to Jay Jasanoff’s brilliant teaching, mentoring, and scholarship, the study of pluperfects was not only not a “had-been,” it was almost a blank slate. -

STUDIES in SOUTHERN WAKASHAN (NOOTKAN) GRAMMAR by Matthew Davidson June 2002 a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Grad

STUDIES IN SOUTHERN WAKASHAN (NOOTKAN) GRAMMAR by Matthew Davidson June 2002 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics iii Acknowledgements I have many people to thank for their contributions to my dissertation. First, I must thank the people of Neah Bay, Washington for their hospitality and generosity during my stay there. The staff of the Makah Cultural and Reseach Center and the Makah Language Program merit special recognition for their unwavering support of my project, so thanks to Janine Bowechop, Yvonne Burkett, Cora Buttram, Keely Parker, Theresa Parker, Maria Pascua, and Melissa Peterson. Of all my friends in Neah Bay, I am most indebted to my primary Makah language consultant, Helma Swan Ward, who spent many patient hours answering questions about Makah and sharing her insights about the language with me. My project has benefited greatly from the labors of my dissertation committee at SUNY Buf- falo, Karin Michelson, Matthew Dryer, and Jean-Pierre Koenig. Their insights concerning both analytic matters and organizational details made the dissertation better than it otherwise would have been. Bill Jacobsen, my outside reader, deserves my gratitude for his meticulous reading of the manuscript on short notice, which resulted in many improvements to the final work. Thanks also to Jay Powell, who facilitated my initial contact with the Makah. I gratefully acknowledge funding for my research from the Jacobs Research Funds and the Mark Diamond Research Fund of the Graduate Student Association of the State University of New York at Buffalo. -

Aorist and Pseudo-Aorist for Svan Atelic Verbs — K. Tuite 0. Introduction. the Kartvelian Or South Caucasian Family Comprises

Aorist and pseudo-aorist for Svan atelic verbs — K. Tuite 0. Introduction. The Kartvelian or South Caucasian family comprises three languages: Georgian, which has been attested in documents going back to the 5th century, Zan (or Laz-Mingrelian) and Svan. In the case of Zan and Svan, there is almost no documentation going back beyond the mid-19th century. There is a concensus among experts that Svan is the outlying member of the family, whose family tree would be as in this diagram: COMMON KARTVELIAN COMMON GEORGIAN-ZAN PREHISTORIC SVAN GEORGIAN ZAN MINGRELIAN LAZ Upper Bal Lower Bal Lashx Lent’ex (Upper Svan dialects) (Lower Svan dialects) In this paper I will look at one segment of the formal system in Svan — in particular, in the more conservative Upper Svan dialects — for coding aspect. In this introductory section I will go over the system of what Kartvelologists term “screeves” (sets of verb forms differing only in person and number), and then the classification of verbs by lexical aspect with which the morphological facts will be compared. 0.1. Screeves and series. In the morphology of verbs in each of the Kartvelian languages, one of the fundamental distinctions is between verb forms derived from the SERIES I OR “PRESENT-SERIES” stem, and forms derived from the SERIES II OR “AORIST-SERIES” stem. We will not go into all of the formal differences between these two stems for the various groups of verbs in each language, save to note that for most verbs the Series I stem contains a suffix (the “series marker” or “present/future stem formant”) which does not appear in Series II forms. -

Linguistics 183, Class Slides, Week 3, Day 4

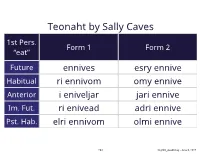

Teonaht by Sally Caves 1st Pers. Form 1 Form 2 “eat” Future ennives esry ennive Habitual ri ennivom omy ennive Anterior i eniveljar jari ennive Im. Fut. ri enivead adri ennive Pst. Hab. elri ennivom olmi ennive 269 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 ASTAPORI VALYRIAN 270 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 5,000 years before the present, the Valyrian Freehold conquered the Ghiscari Empire. High Valyrian replaced Ghiscari as the language of Ghis. 271 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 In Astapor and the other cities, Ghiscari words mixed with High Valyrian grammar and produced a creole that became Astapori Valyrian. 272 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 273 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Ghiscari Astapori Valyrian 274 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 Background High Valyrian Verbs 275 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Subject Agreement with Person and Number 7 Tense/Aspect Combos 2 Modes 2 Voices 276 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Tense/Aspect Present Past Incomplete Anterior (Past/Present) Future Habitual (Past/Present) 277 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Modes Indicative Subjunctive 278 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Voices Active Passive 279 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Present Singular Plural 1st Pers. vestran vestri 2nd Pers. vestraː vestraːt 3rd Pers. vestras vestris 280 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian 1st Pers. Indicative Subjunctive Present vestran vestron Past Inc. vestrilen vestrilon Ant. Pres. vestretan vestreton 281 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian 1st Pers. Indicative Subjunctive Ant. Past vestreten vestreton Future vestrinna vestrilun Hab. Prs. vestrin vestrun Hab. -

Knowledge of Tense, Aspect and Mood in Heritage Language Speakers: the Case of Hybrid Spanish for Business Courses *

Knowledge of Tense, Aspect and Mood in Heritage Language Speakers: The Case of Hybrid Spanish for Business Courses * ESTRELLA RODRIGUEZ ANEL BRANDL Florida State University Florida State University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: This article reports on the grammatical knowledge displayed by a group of Spanish heritage speakers (HSs) when they submitted answers to online homework assignments in a hybrid language course for specific purposes (LSP). Participants received grammatical input through a combination of classroom and online instruction, a hybrid modality. We examined the performance of the HSs on the online assignments, and compared it with a group of L2 learners. The structures of interest were the preterite, imperfect and subjunctive mood in various propositions (volition, doubt, emotion, adverbial temporal clauses, and imperfect subjunctive). Analyses of variance showed no significant differences between the HSs and the L2 learners in the preterite-imperfect contrasts. On the use of subjunctive morphology, HSs were less accurate in subjunctive sentences with adverbial temporal clauses and with the imperfect subjunctive. We conclude that complex subjunctive subordinations remain a vulnerable area in HSs’ end-state grammars even after instruction. We argue that heritage differential acquisition of the subjunctive in naturalistic contexts (vs formal instruction in L2 learners) has had an impact in adult heritage subjunctive knowledge. LSP courses may help them integrate language-related competencies via discourse diversity found in non-academic contexts by creating connections to other disciplines. 1. Introduction The field of Spanish heritage language research has been prolific in recent years, (Cuza & López Otero, 2016; Foote, 2010; Montrul et al., 2014; Montrul & Perpiñán, 2011; Pascual y Cabo & Gómez Soler, 2015; among others). -

Chapter 29 the Imperfect Indicative Active Compound Verbs 29.2 The

Chapter 29 _______________________________ The Imperfect Indicative Active Compound Verbs _____________________ 29.1 So far we have used verbs in the Present and the Future tenses. Now we come to one of the Past tenses of the verb - the Imperfect . The Imperfect is built upon the Present stem of the verb. It has the name "Imperfect" because it does not indicate that an action has been completed in the past. It is used to express "I was doing something" or "I used to do something" - over a period of time, or repeatedly, rather than just once. Note that, particularly when conversations are reported, Greek may use the present, rather than a past tense. This is not bad Greek grammar - it is known as the " Historical Present ", and is done on purpose, to make the action seem more immediate to the reader. There is no Imperfect Subjunctive, Optative, Imperative, Infinitive, or Participle. Besides the Imperfect, there are some other past tenses in Greek, which we will meet later, but most of them have several things in common. 1. A past tense usually has an ε- in front of the verb stem. This is called an " augment " (it is added to the stem, making it longer). The Augment is equivalent to the English "-ed" at the end of a verb - I walk, I walked. 2. Sets of personal endings are used, which are very similar to the endings we have already learned. 29.2 The basic pattern for the Imperfect Indicative Active is I ἐ -STEM -ον ἐ -STEM -οεν we you (singular) ἐ -STEM -ες ἐ -STEM -ετε y'all he/she/it ἐ -STEM -εν ἐ -STEM -ον they For λέγω , this becomes I was saying ἔλεγον ἐλέγοµεν we were saying you were saying ἔλεγες ἐλέγετε y'all were saying he/she/it was saying ἔλεγεν ἔλεγον they were saying We already know the endings for the First and Second Persons Plural. -

Journal of Biblical Literature

6o JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE. Waw Consecutive with the Perfect in Hebrew. PROF. GEORGE RICKER BERRY, PH.D. HAMILTON, lt. Y. N order that the position here taken with reference to waw I consecutive with the perfect may be clearly understood, it is necessary that brief reference should be made to some other related matters, viz., the gener.al theory of the tenses, and the use of the imperfect with waw consecutive. The prevailing theory of the Semitic tenses is that they express merely time-quality, not time-relation, that the imperfect expresses simply incomplete action, the perfect completed action. Yet there are not wanting adherents of the opposite view, such as Konig, who does not, to be sure, limit the meaning to time-relation, but makes that the principal idea (see his Syntax). The view of the writer is that the fundamental meaning of the Hebrew tenses, as of the Semitic tenses in general, is the expression of time-relation, that the Hebrew perfect expresses past action, the Hebrew imperfect future action. The participle is not a tense, and does not express relation, but quality, i.e. continuing action. The time-relation is most frequently the time in relation to the real time of the writer or speaker, but it may also be in relation to some other action, or in relation to some assumed standpoint of the writer or speaker. Much of what is to follow, however, would not be greatly affected by one's position on. this fundamental question of tense meaning. The two views are very similar in their practical working out in details.