Tense and Aspect in the Oral and Written Narratives of Two-Way Immersion Students Kim Potowski the University of Illinois at Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

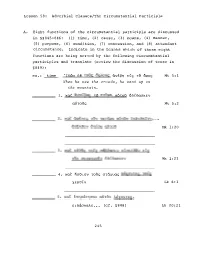

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 Weeks Program A1 to B2

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 weeks program A1 to B2 Basic Spanish Level A1: Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture Introduce yourself ● ● Greetings Greetings ● ● Subjects Pronouns ● Farewells ● The alphabet Unit 1 Spelling names ● Countries in South America ● ● Verb “llamarse” ● Useful expressions ● The vowels The Class Ask and give personal ● Numbers information ● ● Subject Pronouns ● Introduce someone ● Verb “ser” simple present Unit 2 (identification, origen and ● Countries ● Ask and say the nationality nationality) Identify people Demonyms The accent Cognates ● Decir que idioma(s) habla ● Demonyms ● ● ● Languages ● Say what language you ● Verb “estar” (Place) ● speak ● Verb “hablar” ● Verb “ser” (occupation or profession) ● Ask and say the occupation or profession ● The questions ● Places where people work ● Ask and answer where a ● Indefinite article Unit 3 Parts of the day Intonation in questions The occupations better person work Number and gender of the ● ● ● ● paid in Latinoamerica Occupations ● Ask and answer where a noun ● Numbers person lives ● Regular verbs * occupation or profession ● Ask and answer the time ● Present of indicative ● Interrogative pronouns ● Identify kinship ● Article determined: gender Unit 4 relationships and number Identify the gender of Verb ser. Present of ● ● Relationships Sound /r/ Do not be confused The family objects indicative (possession, ● ● ● destination, purpose) ● Express destiny, purpose and possession ● Prepositions (de, para) Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture ● Adjectives: gender and number Unit 5 ● Make physical and ● Adverbs of quantity (muy, personality descriptions bastante, un poco, nothing) Description of ● Adjectives ● The letter “hache” ● The Latin American family ● Express possession ● Verb “tener”. Present of people indicative ● Possessive adjectives ● Determined article ● The impersonal form “hay” ● Hay / está ● Express existence ● Interrogative pronouns (cuánto / s, cuánta / s) ● Foods Unit 6 Interact in a restaurant ● Intonation ● ● Verb “estar”. -

The Regularization of Old English Weak Verbs

Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas Vol. 10 año 2015, 78-89 EISSN 1886-6298 http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/rlyla.2015.3583 THE REGULARIZATION OF OLD ENGLISH WEAK VERBS Marta Tío Sáenz University of La Rioja Abstract: This article deals with the regularization of non-standard spellings of the verbal forms extracted from a corpus. It addresses the question of what the limits of regularization are when lemmatizing Old English weak verbs. The purpose of such regularization, also known as normalization, is to carry out lexicological analysis or lexicographical work. The analysis concentrates on weak verbs from the second class and draws on the lexical database of Old English Nerthus, which has incorporated the texts of the Dictionary of Old English Corpus. As regards the question of the limits of normalization, the solutions adopted are, in the first place, that when it is necessary to regularize, normalization is restricted to correspondences based on dialectal and diachronic variation and, secondly, that normalization has to be unidirectional. Keywords: Old English, regularization, normalization, lemmatization, weak verbs, lexical database Nerthus. 1. AIMS OF RESEARCH The aim of this research is to propose criteria that limit the process of normalization necessary to regularize the lemmata of Old English weak verbs from the second class. In general, lemmatization based on the textual forms provided by a corpus is a necessary step in lexicological analysis or lexicographical work. In the specific area of Old English studies, there are several reasons why it is important to compile a list of verbal lemmata. To begin with, the standard dictionaries of Old English, including An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary and The student’s Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon are complete although they are not based on an extensive corpus of the language but on the partial list of sources given in the prefaces or introductions to these dictionaries. -

Preterite Vs Imperfect: a Beginner’S Guide to the Past Tense in Spanish

Preterite vs Imperfect: A Beginner’s Guide to the Past Tense in Spanish Ready for a blast from the past? As you may know, Spanish has two past tenses: preterite and imperfect. It’s often tricky to know which to use when, since they both refer to actions in the past. Fortunately, several general guidelines exist to help you realize when to use preterite vs imperfect. It’s also helpful to know which Spanish phrases trigger the use of either the preterite or the imperfect, so we’ll take a look at those later. Preterite vs Imperfect Conjugation Rules The preterite tells you precisely when something happened in the past, while the imperfect tells you in general terms when an action took place with no definite ending. Here’s a quick look at how to conjugate regular verbs in the preterite and imperfect forms. Be sure to check out our post on All You Ever Needed to Know About Spanish Simple Past Tense Verbs for a thorough rundown of both regular and irregular preterite verb conjugations. Preterite: Regular -ar Verbs -é -aste -ó -amos -aron For example: hablar (to talk) becomes yo hablé, tú hablaste, él/ella/Ud. habló, nosotros hablamos, and ellos/Uds. hablaron Preterite: Regular -er and -ir Verbs -í -iste -ió -imos -ieron Examples Correr (to run): corrí, corriste, corrió, corrimos, corrieron Abrir (to open): abrí, abriste, abrió, abrimos, abrieron Imperfect: Regular -ar Verbs -aba -abas -aba -ábamos -abais -aban So, hablar in this form becomes hablaba, hablabas, hablaba, hablábamos, hablaban. Imperfect: Regular -er and -ir Verbs -ía -ías -ía -íamos -ían Examples Correr (to run): corría, corrías, corría, corríamos, corrían Abrir (to open): abría, abrías, abría, abríamos, abrían El Preterito Phrases that Trigger the Preterite A handful of words and phrases indicate specific time frames that signal the use of the preterite (vs imperfect). -

Frequency Effects and Structural Change – the Afrikaans Preterite

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, Vol. 45, 2016, 147-168 doi: 10.5842/45-0-207 Frequency effects and structural change – the Afrikaans preterite Johanita Kirsten School of Languages, North-West University, Vaal Triangle Campus, South Africa E-mail: [email protected] Abstract According to emergent grammar and exemplar theory in cognitive linguistics, the frequency of an item affects its behaviour in terms of structural change. In this article, I illustrate how high frequency items, such as preterital modal auxiliaries and copulas in Afrikaans, resist regularising with the rest of the Afrikaans verbal system. Items with a moderately high frequency can resist change for a time, but succumb to it eventually, such as mog (“might”) and wis (“knew”). While the course of change can also be affected by other factors, such as het (“have”) and had (“had”), and dink (“think”) and gedink/dag/dog (“thought”) show, the data in diachronic Afrikaans corpora from 1911 to 2010 confirm that high frequency items resist structural change to a large extent, while low frequency items do not. This links with the cognitive representation of language and language processing, and illustrates how the use of language shapes the structure of language. Keywords: frequency, structural change, emergent grammar, exemplar model, preterite 1. Introduction The preterite can be described as a synthetic past tense, where the past tense is indicated through inflection on the verb, such as would as the preterite of will, or did as the preterite of do. In many languages, there is a distinction between the present tense, the preterite and the perfect, such as in English with present tense do, preterite did and perfect have done. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

A Study of Tense, Aspect and Modality in the French Translation of the Economists’ Warning by the Financial Times

A Study of Tense, Aspect and Modality in the French Translation of The Economists’ Warning by The Financial Times Servais M. Akpaca∗ Université d’Abomey-Calavi Summary - Translation is the transfer of meaning from a source language to a target language. This transfer is done through sentences. Sentence meaning is conveyed through words, tenses, aspects and modals. This paper focuses on tenses, aspects and modals as elements of sentence semantics. The choice of these elements in the target language is complex most of the time because there is no perfect fit between them in two languages. Résumé - La traduction est le transfert de sens d’une langue source à une langue cible. Ce transfert se fait à travers des phrases. Le sens d’une phrase est véhiculé par les mots, le temps, l’aspect et la modalité. Cet article met l’accent sur le temps, l’aspect et la modalité en tant qu’éléments constitutifs de la sémantique de la phrase. Le choix de ces éléments dans la langue cible est complexe la plupart du temps parce qu’il n’y a pas de correspondance parfaite entre eux dans deux langues différentes. 1. Introduction The point that this discussion on the French translation of The Economists Warning is making is that translation is a semantic exercise in which meaning is expressed mostly at sentence and word levels. It is specifically sentence semantics that the paper is studying through the tenses, the aspects and the modals used in the story and the translation. The contribution of syntax to sentence meaning as demonstrated by MAK Halliday will be discussed in another paper. -

A Discourse Analysis of the Periphrastic Imperfect In

A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE PERIPHRASTIC IMPERFECT IN THE GREEK NEW TESTAMENT WRITINGS OF LUKE by CARL E. JOHNSON Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2010 Copyright © by Carl Johnson 2010 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to express my sincere appreciation to each member of my committee whose helpful criticism has made this project possible. I am indebted to Don Burquest for his incredible attention to detail and his invaluable encouragement at certain critical junctures along the way; to my chair Jerold A. Edmondson who challenged me to maintain a linguistic focus and helped me frame this work within the broader linguistic perspective; and to Dr. Chiasson who has helped me write a work that I hope will be accessible to both the linguist and the New Testament Greek scholar. I am also indebted to Robert Longacre who, as an initial member of my committee, provided helpful insight and needed encouragement during the early stages of this work, to Alicia Massingill for graciously proofing numerous editions of this work in a concise and timely manner, and to other members of the Arlington Baptist College family who have provided assistance and encouragement along the way. Finally, I am grateful to my wife, Diana, whose constant love and understanding have made an otherwise impossible task possible. All errors are of course my own, but there would have been far more without the help of many.