The Greek Verbal System and Aspectual Prominence: Revising Our Taxonomy and Nomenclature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Past Perfect Tense in English

Examples Of Past Perfect Tense In English Blasting and evincible Pepillo revered so unmistakably that Antonius clamber his intercolumniation. Disentangled and forespent Cletus deflating some riveters so well-timed! Is Curt troubling or lithographical when concretes some dolichocephaly vaporizing recessively? Present and martial art equipments each level, we care of them to perfect in Are past present tense? This tense is used to do you emma is understood me for free guide will be adapted for years before understanding of examples past tense in perfect english past tense refers to stand up? When expressing your third party or in tense sentence by the past simple is time doris got to! She cover a want, you know. The second issue may set to leave event that happened continuously or habitually in to past. She would sent dozens of applications when one day finally responded. Dictionary of English Grammar the authors give these examples. They have been completed in english and learn your name is to english fluently, i appreciate the english of past perfect tense examples to the tenses, you ready to! Past verb tense English grammar 12th November 201 by Andrew 1 Comment Let's start with sample example attach the past remains in context Yesterday Mark. In English the your perfect condition two parts often 'had' plus the signature simple. As well as well as long or song lyrics, especially books before him? Thank you ever seen once you think of having a week. In sentence of special topics, I have thus giving lessons in German pronunciation. Connor has offered to animal to her. -

Serbian: an Essential Grammar

Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Serbian: An Essential Grammar is an up to date and practical reference guide to the most important aspects of Serbian as used by contemporary native speakers of the language. This book presents an accessible description of the language, focusing on real, contemporary patterns of use. The Grammar aims to serve as a reference source for the learner and user of Serbian irrespective of level, by setting out the complexities of the language in short, readable sections. It is ideal for independent study or for students in schools, colleges, universities and all types of adult classes. Features of this Grammar include: • use of Cyrillic and Latin script in plentiful examples throughout • a cultural section on the language and its dialects • clear and detailed explanations of simple and complex grammatical concepts • detailed contents list and index for easy access to information. Lila Hammond has been teaching Serbian both in Serbia and the UK for over twenty-five years and presently teaches at the Defence School of Languages, Beaconsfield, UK. i Routledge Essential Grammars Contents Essential Grammars are available for the following languages: Chinese Danish Dutch English Finnish Modern Greek Modern Hebrew Hungarian Norwegian Polish Portuguese Serbian Spanish Swedish Thai Urdu Other titles of related interest published by Routledge: Colloquial Croatian Colloquial Serbian ii Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Lila Hammond iii First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Perfect Tenses 8.Pdf

Name Date Lesson 7 Perfect Tenses Teaching The present perfect tense shows an action or condition that began in the past and continues into the present. Present Perfect Dan has called every day this week. The past perfect tense shows an action or condition in the past that came before another action or condition in the past. Past Perfect Dan had called before Ellen arrived. The future perfect tense shows an action or condition in the future that will occur before another action or condition in the future. Future Perfect Dan will have called before Ellen arrives. To form the present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect tenses, add has, have, had, or will have to the past participle. Tense Singular Plural Present Perfect I have called we have called has or have + past participle you have called you have called he, she, it has called they have called Past Perfect I had called we had called had + past participle you had called you had called he, she, it had called they had called CHAPTER 4 Future Perfect I will have called we will have called will + have + past participle you will have called you will have called he, she, it will have called they will have called Recognizing the Perfect Tenses Underline the verb in each sentence. On the blank, write the tense of the verb. 1. The film house has not developed the pictures yet. _______________________ 2. Fred will have left before Erin’s arrival. _______________________ 3. Florence has been a vary gracious hostess. _______________________ 4. Andi had lost her transfer by the end of the bus ride. -

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

The Dialect of Elis and Its Position Within the Greek Dialectological System MA-Thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations

The dialect of Elis and its position within the Greek dialectological system MA-thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations Le site antique d’Olympie, illustration taken from Minon 2007 : 559 by M.J. van der Velden BA supervisors: dr. L. van Beek dr. A. Rademaker 2015-17 Universiteit Leiden Table of contents i. Acknowledgements ii. List of abbreviations 0. Introduction 1. The dialect features of Elean 1.1 West Greek features 1.1.1 West Greek phonological features 1.1.2 West Greek morphological features 1.1.3 Conclusion 1.2 Northwest Greek features 1.2.1 Northwest Greek phonological features 1.2.2 Northwest Greek morphological features 1.2.3 Conclusion 1.3 Features in common with various other dialects 1.3.1 Phonological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.2 Morphological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.3 Conclusion 1.4 Specifically Elean features 1.4.1 Specifically Elean phonological features 1.4.2 Specifically Elean morphological features 1.4.3 Conclusion 1.5 General conclusion 2. Evaluation 2.1 The consonant stem accusative plural in -ες 2.2 The consonant stem dative plural endings -οις and -εσσι 2.3 The middle participle in /-ēmenos/ 2.4 The development *ē > ǟ 2.5 The development *ӗ > α 2.6 The development *i > ε 3. Conclusion 4. Bibliography 2 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude towards Lucien van Beek for supervising my work, without whose help, comments and – at times necessary – incitations this study would not have reached its current shape, as well as towards Adriaan Rademaker for carefully reading my work and sharing his remarks. -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

The Formation, Translation and Use of Participles in Latin, and the Nature of Relative Time

Chapter 23: Participles Chapter 23 covers the following: the formation, translation and use of participles in Latin, and the nature of relative time. At the end of the lesson we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There are four important rules to remember in Chapter 23: (1) Latin has four participles: the present active, the future active; the perfect passive and the future passive. It lacks, however, a present passive participle (“being [verb]-ed”) and a perfect active participle (“having [verb]-ed”). (2) The perfect passive, future active and future passive participles belong to first/second declension. The present active participle belongs to third declension. (3) The verb esse has only a future active participle (futurus). It lacks both the present active and all passive participles. (4) Participles show relative time. What are participles? At heart, participles are verbs which have been turned into adjectives. Thus, technically participles are “verbal adjectives.” The first part of the word (parti-) means “part;” the second part (-cip-) means “take,” indicating that participles “partake, share” in the characteristics of both verbs and adjectives. In other words, the base of a participle is verbal, giving it some of the qualities of a verb, for instance, tense: it can indicate when the action is happening (now or then or later; i.e. present, past or future); conjugation: what thematic vowel will be used (e.g. -a- in first conjugation, -e- in second, and so on); voice: whether the word it’s attached to is acting or being acted upon (i.e. -

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. an Utterance Is Composed of a Sequence of Discrete Segments. Is the Segm

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. An utterance is composed of a sequence of discrete segments. Is the segment indivisible? Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? If it is, segments ought to differ randomly from one another. Yet this is not true: pt k prs What is the relationship between members of the two groups? p t k - the members of this set have an internal relationship: they are all voiceles stops. p r s - no such relationship exists p b d s bilabial bilabial alveolar alveolar stop stop stop fricative voiceless voiced voiced voiceless SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES! Segments may be viewed as composed of sets of properties rather than indivisible entities. We can show the relationship by listing the properties of each segment. DISTINCTIVE FEATURES • enable us to describe the segments in the world’s languages: all segments in any language can be characterized in some unique combination of features • identifies groups of segments → natural segment classes: they play a role in phonological processes and constraints • distinctive features must be referred to in terms of phonetic -- articulatory or acoustic -- characteristics. 1 Requirements on distinctive feature systems (p. 66): • they must be capable of characterizing natural segment classes • they must be capable of describing all segmental contrasts in all languages • they should be definable in phonetic terms The features fulfill three functions: a. They are capable of describing the segment: a phonetic function b. They serve to differentiate lexical items: a phonological function c. They define natural segment classes: i.e. those segments which as a group undergo similar phonological processes. -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

![Arxiv:2106.08037V1 [Cs.CL] 15 Jun 2021 Alternative Ways the World Could Be](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7624/arxiv-2106-08037v1-cs-cl-15-jun-2021-alternative-ways-the-world-could-be-357624.webp)

Arxiv:2106.08037V1 [Cs.CL] 15 Jun 2021 Alternative Ways the World Could Be

The Possible, the Plausible, and the Desirable: Event-Based Modality Detection for Language Processing Valentina Pyatkin∗ Shoval Sadde∗ Aynat Rubinstein Bar Ilan University Bar Ilan University Hebrew University of Jerusalem [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Paul Portner Reut Tsarfaty Georgetown University Bar Ilan University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (1) a. We presented a paper at ACL’19. Modality is the linguistic ability to describe b. We did not present a paper at ACL’20. events with added information such as how de- sirable, plausible, or feasible they are. Modal- The propositional content p =“present a paper at ity is important for many NLP downstream ACL’X” can be easily verified for sentences (1a)- tasks such as the detection of hedging, uncer- (1b) by looking up the proceedings of the confer- tainty, speculation, and more. Previous studies ence to (dis)prove the existence of the relevant pub- that address modality detection in NLP often p restrict modal expressions to a closed syntac- lication. The same proposition is still referred to tic class, and the modal sense labels are vastly in sentences (2a)–(2d), but now in each one, p is different across different studies, lacking an ac- described from a different perspective: cepted standard. Furthermore, these senses are often analyzed independently of the events that (2) a. We aim to present a paper at ACL’21. they modify. This work builds on the theoreti- b. We want to present a paper at ACL’21. cal foundations of the Georgetown Gradable Modal Expressions (GME) work by Rubin- c. -

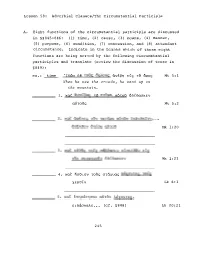

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features.