The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long and Short Adjunct Fronting in HPSG

Long and Short Adjunct Fronting in HPSG Takafumi Maekawa Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar Linguistic Modelling Laboratory, Institute for Parallel Processing, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Held in Varna Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2006 CSLI Publications pages 212–227 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2006 Maekawa, Takafumi. 2006. Long and Short Adjunct Fronting in HPSG. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Varna, 212–227. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract The purpose of this paper is to consider the proper treatment of short- and long-fronted adjuncts within HPSG. In the earlier HPSG analyses, a rigid link between linear order and constituent structure determines the linear position of such adjuncts in the sentence-initial position. This paper argues that there is a body of data which suggests that ad- junct fronting does not work as these approaches predict. It is then shown that linearisation-based HPSG can provide a fairly straightfor- ward account of the facts. 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to consider the proper treatment of short- and long-fronted adjuncts within HPSG. ∗ The following sentences are typical examples. (1) a. On Saturday , will Dana go to Spain? (Short-fronted adjunct) b. Yesterday I believe Kim left. (Long-fronted adjunct) In earlier HPSG analyses, a rigid link between linear order and constituent structure determines the linear position of such adverbials in the sen- tence-initial position. I will argue that there is a body of data which sug- gests that adjunct fronting does not work as these approaches predict. -

Polarity and Modality

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Polarity and Modality A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Vincent Homer 2011 © Copyright by Vincent Homer 2011 The dissertation of Vincent Homer is approved. Timothy Stowell Philippe Schlenker, Committee Co-chair Dominique Sportiche, Committee Co-chair University of California, Los Angeles 2011 ii A` mes chers parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................. 1 1.1 Chapter2:DomainsofPolarityItems . 2 1.2 Chapter3: PresuppositionsandNPILicensing . .... 5 1.3 Chapter 4: Neg-raising and Positive Polarity: The View fromModals. 7 1.4 Chapter 5: Actuality Entailments and Aspectual Coercion....... 9 2 Domains of Polarity Items ......................... 13 2.1 Introduction............................... 13 2.2 RevivingFlip-flop............................ 16 2.2.1 OperatorsorEnvironments? . 17 2.2.2 Flip-flopwithWeakNPIs . 22 2.2.3 Flip-flopwithStrongNPIs . 36 2.2.4 Flip-flopwithPPIs . .. .. .. .. .. .. 39 2.3 Dependency............................... 44 2.3.1 MultipleNPIs.......................... 45 2.3.2 MultiplePPIs.......................... 47 2.3.3 Co-occurrenceofNPIsandPPIs . 54 2.4 FurtherEvidenceforDomains . 61 2.4.1 MonotonicityDisruption . 61 2.4.2 Scope of Deontic must ..................... 72 2.5 Cyclicity................................. 77 iv 2.6 A Hypothesis about any asaPPIinDisguise. 81 2.7 Some isnotanIntervener ........................ 88 2.8 Szabolcsi2004 ............................ -

Representation of Inflected Nouns in the Internal Lexicon

Memory & Cognition 1980, Vol. 8 (5), 415423 Represeritation of inflected nouns in the internal lexicon G. LUKATELA, B. GLIGORIJEVIC, and A. KOSTIC University ofBelgrade, Belgrade, Yugoslavia and M.T.TURVEY University ofConnecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06268 and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 The lexical representation of Serbo-Croatian nouns was investigated in a lexical decision task. Because Serbo-Croatian nouns are declined, a noun may appear in one of several gram matical cases distinguished by the inflectional morpheme affixed to the base form. The gram matical cases occur with different frequencies, although some are visually and phonetically identical. When the frequencies of identical forms are compounded, the ordering of frequencies is not the same for masculine and feminine genders. These two genders are distinguished further by the fact that the base form for masculine nouns is an actual grammatical case, the nominative singular, whereas the base form for feminine nouns is an abstraction in that it cannot stand alone as an independent word. Exploiting these characteristics of the Serbo Croatian language, we contrasted three views of how a noun is represented: (1) the independent entries hypothesis, which assumes an independent representation for each grammatical case, reflecting its frequency of occurrence; (2) the derivational hypothesis, which assumes that only the base morpheme is stored, with the individual cases derived from separately stored inflec tional morphemes and rules for combination; and (3) the satellite-entries hypothesis, which assumes that all cases are individually represented, with the nominative singular functioning as the nucleus and the embodiment of the noun's frequency and around which the other cases cluster uniformly. -

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Answering Particles: Findings and Perspectives

ANSWERING PARTICLES: FINDINGS AND PERSPECTIVES Emilio Servidio ([email protected]) 1. ANSWERING SYSTEMS 1.1. Historical introduction It is not uncommon for descriptive or prescriptive grammars to observe that a given language follows certain regularities when answering a polar question. Linguistics, on the other hand, has seldom paid much attention to the topic until recent years. The forerunner, in this respect, is Pope (1973), who sketched a typology of polar answering systems that followed in the steps of recent typological efforts on related topics (Ultan 1969, Moravcsik 1971 on polar questions). In the last decade, on the other hand, contributions have appeared from two different strands of theoretical research, namely, the syntactic approach to ellipsis as deletion (Kramer & Rawlins 2010; Holmberg 2013, 2016) and the study of conversation dynamics (Farkas & Bruce 2010; Krifka 2013, 2015; Roelofsen & Farkas 2015). This contribution aims at offering a critical overview of the state of the art on the topic1. In the remainder of this section, a typological sketch of answering systems will be drawn, before moving on to the extant analyses in section 2. In section 3, recent experimental work will be discussed. Section 4 summarizes and concludes. 1.2. Basic typology This survey will mainly deal with polar answers, defined as responding moves that address and fully satisfy the discourse requirements of a polar question. A different but closely related topic is the one of replies, i.e., moves that respond to a statement. Together, these moves go under the name of responses2. One first piece of terminology is the distinction between short and long responses. -

Third Declension, That Is, Consonant-Stem Nouns; Patterns I

Chapter 7: Third-Declension Nouns Chapter 7 covers the following: third declension, that is, consonant-stem nouns; patterns in the formation of the nominative singular of third declension; and the agreement between third- declension nouns and first/second-declension adjectives. At the end of the lesson, we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There is only one important rule to remember here: the genitive singular ending in third declension is -is . We’ve already encountered first- and second-declension nouns. Now we’ll address the third. A fair question to ask, and one which some of you may be asking, is why is there a third declension at all? Third declension is Latin’s “catch-all” category for nouns. Into it have been put all nouns whose bases end with consonants ─ any consonant! That makes third declension very different from first and second declension. First declension, as you’ll remember, is dominated by a-stem nouns like femina and cura . Second declension is dominated by o- or u-stem nouns like amicus or oculus . Those vowels give those declensions a certain consistency, but the same is not true of third declension where one form, the nominative singular, is affected by the fact that its ending -s runs into the wide variety of consonants found at the ends of the bases of third-declension nouns, and the collision of those consonants causes irregular forms to appear in the nominative singular. That’s the bad news. The good news is that only one case and number is affected by this, the nominative singular. -

56. Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity When Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions

University of Southern California Law From the SelectedWorks of Thomas D. Lyon December 19, 2016 56. Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity when Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions. Angela D. Evans, Brock University Stacia N. Stolzenberg, Arizona State University Thomas D. Lyon Available at: https://works.bepress.com/thomaslyon/139/ Psychology, Public Policy, and Law © 2017 American Psychological Association 2017, Vol. 23, No. 2, 191–199 1076-8971/17/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/law0000116 Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity When Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions Angela D. Evans Stacia N. Stolzenberg Brock University Arizona State University, Tempe Thomas D. Lyon University of Southern California “Do you know” and “Do you remember” (DYK/R) questions explicitly ask whether one knows or remembers some information while implicitly asking for that information. This study examined how 4- to 9-year-old (N ϭ 104) children testifying in child sexual abuse cases responded to DYK/R wh- (who, what, where, why, how, and which) and yes/no questions. When asked DYK/R questions containing an implicit wh- question requesting information, children often provided unelaborated “yes” responses. Attorneys’ follow-up questions suggested that children usually misunderstood the pragmatics of the questions. When DYK/R questions contained an implicit yes/no question, unelaborated “yes” or “no” responses could be responding to the explicit or the implicit questions resulting in referentially ambig- uous responses. Children often provided referentially ambiguous responses and attorneys usually failed to disambiguate children’s answers. Although pragmatic failure following DYK/R wh- questions de- creased with age, the likelihood of referential ambiguity following DYK/R yes/no questions did not. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

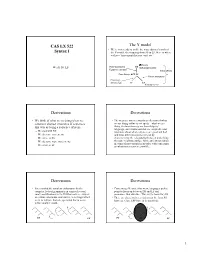

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras To cite this version: Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras. Romani Syntactic Typology. Yaron Matras; Anton Tenser. The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics, Springer, pp.187-227, 2020, 978-3-030-28104- 5. 10.1007/978-3-030-28105-2_7. halshs-02965238 HAL Id: halshs-02965238 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02965238 Submitted on 13 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Romani syntactic typology Evangelia Adamou and Yaron Matras 1. State of the art This chapter presents an overview of the principal syntactic-typological features of Romani dialects. It draws on the discussion in Matras (2002, chapter 7) while taking into consideration more recent studies. In particular, we draw on the wealth of morpho- syntactic data that have since become available via the Romani Morpho-Syntax (RMS) database.1 The RMS data are based on responses to the Romani Morpho-Syntax questionnaire recorded from Romani speaking communities across Europe and beyond. We try to take into account a representative sample. We also take into consideration data from free-speech recordings available in the RMS database and the Pangloss Collection. -

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. an Utterance Is Composed of a Sequence of Discrete Segments. Is the Segm

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. An utterance is composed of a sequence of discrete segments. Is the segment indivisible? Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? If it is, segments ought to differ randomly from one another. Yet this is not true: pt k prs What is the relationship between members of the two groups? p t k - the members of this set have an internal relationship: they are all voiceles stops. p r s - no such relationship exists p b d s bilabial bilabial alveolar alveolar stop stop stop fricative voiceless voiced voiced voiceless SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES! Segments may be viewed as composed of sets of properties rather than indivisible entities. We can show the relationship by listing the properties of each segment. DISTINCTIVE FEATURES • enable us to describe the segments in the world’s languages: all segments in any language can be characterized in some unique combination of features • identifies groups of segments → natural segment classes: they play a role in phonological processes and constraints • distinctive features must be referred to in terms of phonetic -- articulatory or acoustic -- characteristics. 1 Requirements on distinctive feature systems (p. 66): • they must be capable of characterizing natural segment classes • they must be capable of describing all segmental contrasts in all languages • they should be definable in phonetic terms The features fulfill three functions: a. They are capable of describing the segment: a phonetic function b. They serve to differentiate lexical items: a phonological function c. They define natural segment classes: i.e. those segments which as a group undergo similar phonological processes. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C.