1 the Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polarity and Modality

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Polarity and Modality A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Vincent Homer 2011 © Copyright by Vincent Homer 2011 The dissertation of Vincent Homer is approved. Timothy Stowell Philippe Schlenker, Committee Co-chair Dominique Sportiche, Committee Co-chair University of California, Los Angeles 2011 ii A` mes chers parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................. 1 1.1 Chapter2:DomainsofPolarityItems . 2 1.2 Chapter3: PresuppositionsandNPILicensing . .... 5 1.3 Chapter 4: Neg-raising and Positive Polarity: The View fromModals. 7 1.4 Chapter 5: Actuality Entailments and Aspectual Coercion....... 9 2 Domains of Polarity Items ......................... 13 2.1 Introduction............................... 13 2.2 RevivingFlip-flop............................ 16 2.2.1 OperatorsorEnvironments? . 17 2.2.2 Flip-flopwithWeakNPIs . 22 2.2.3 Flip-flopwithStrongNPIs . 36 2.2.4 Flip-flopwithPPIs . .. .. .. .. .. .. 39 2.3 Dependency............................... 44 2.3.1 MultipleNPIs.......................... 45 2.3.2 MultiplePPIs.......................... 47 2.3.3 Co-occurrenceofNPIsandPPIs . 54 2.4 FurtherEvidenceforDomains . 61 2.4.1 MonotonicityDisruption . 61 2.4.2 Scope of Deontic must ..................... 72 2.5 Cyclicity................................. 77 iv 2.6 A Hypothesis about any asaPPIinDisguise. 81 2.7 Some isnotanIntervener ........................ 88 2.8 Szabolcsi2004 ............................ -

Feature Clusters

Chapter 2 Feature Clusters 1. Introduction The goal of this Chapter is to address certain issues that pertain to the properties of feature clusters and the rules that govern their co-occurrences. Feature clusters come as fully specified (e.g. [+c+m] associated with people in (1a)) and ‘underspecified’ (e.g. [-c] associated with acquaintances in (1a)). Such partitioning of feature clusters raises the question of the implications of notions such as ‘underspecified’ and ‘fully specified’ in syntactic and semantic terms. The sharp contrast between the grammaticality of the middle derivation in (1b) and ungrammaticality of (1c) takes the investigation into rules that regulate the co-realization of feature clusters of the base-verb (1a). Another issue that is discussed in this Chapter is the status of arguments versus adjuncts in the Theta System. This topic is also of importance for tackling the issue of middles in Chapter 4 since – intriguingly enough – whereas (1c) is not an acceptable middle derivation in English, (1d) is. (1a) People[+c+m] don’t send expensive presents to acquaintances[-c] (1b) Expensive presents send easily. (1c) *Expensive presents send acquaintances easily. (1d) Expensive presents do not send easily to foreign countries. In section 2 of this Chapter, the properties of feature clusters with respect to syntax and semantics are examined. Section 3 sets the background for Section 4 by addressing the issue of conditions on thematic roles that have been assumed in the literature. Section 4 deals with conditions that govern the co-occurrences of feature clusters in the Theta System. The discussion in section 4 will necessitate the discussion of adjunct versus argument status of certain phrases. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Principles and Parameters Set out from Europe

Principles and Parameters Set Out from Europe Mark Baker MIT Linguistics 50th Anniversary, 9 December 2011 1. The Opportunity Afforded (1980-1995) The conception of universal principles plus finite discrete parameters of variation offered: The hope and challenge of simultaneously doing justice to both the similarities and the differences among languages. The discovery and expectation of patterns in crosslinguistic variation. These were first presented with respect to “medium- sized” differences in European languages: The subjacency parameter (Rizzi, 1982) The pro-drop parameter (Chomsky, 1981; Kayne, 1984; Rizzi, 1982) They were then perhaps extended to the largest differences among languages around the world: The configurationality parameter(s) (Hale, 1983) “The more languages differ, the more they are the same” Example 1: Mohawk (Baker, 1988, 1991, 1996) Mohawk seems nonconfigurational, with no “syntactic” evidence of a VP containing the object and not the subject: (1) a. Sak wa-ha-hninu-’ ne ka-nakt-a’. Sak FACT-3mS-buy-PUNC NE 3n-bed-NSF b. Sak kanakta wahahninu’ c. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ ne Sak d. Kanakta’ Sak wahahninu’ e. Wahahninu’ ne Sak ne kanakta’ f. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ ne Sak g. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ h. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ i. Sak wahahninu’ j. Wahahninu’ ne Sak k. Wahahninu. All: ‘Sak/he bought a bed/it.’ There are also no differences between subject and object in binding (Condition C, neither c- commands the other) or wh-extraction (both are islands, no “subject condition”) (Baker 1992) Mohawk is polysynthetic (agreement, noun incorporation, applicative, causative, directionals…): (2) a. Sak wa-ha-nakt-a-hninu-’ Sak FACT-3mS-bed-Ø-buy-PUNC ‘Sak bought the bed.’ 1 b. -

The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

The syntax of answers to negative yes/no-questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University 1. Introduction This paper will argue that answers to polar questions or yes/no-questions (YNQs) in English are elliptical expressions with basically the structure (1), where IP is identical to the LF of the IP of the question, containing a polarity variable with two possible values, affirmative or negative, which is assigned a value by the focused polarity expression. (1) yes/no Foc [IP ...x... ] The crucial data come from answers to negative questions. English turns out to have a fairly complicated system, with variation depending on which negation is used. The meaning of the answer yes in (2) is straightforward, affirming that John is coming. (2) Q(uestion): Isn’t John coming, too? A(nswer): Yes. (‘John is coming.’) In (3) (for speakers who accept this question as well formed), 1 the meaning of yes alone is indeterminate, and it is therefore not a felicitous answer in this context. The longer version is fine, affirming that John is coming. (3) Q: Isn’t John coming, either? A: a. #Yes. b. Yes, he is. In (4), there is variation regarding the interpretation of yes. Depending on the context it can be a confirmation of the negation in the question, meaning ‘John is not coming’. In other contexts it will be an infelicitous answer, as in (3). (4) Q: Is John not coming? A: a. Yes. (‘John is not coming.’) b. #Yes. In all three cases the (bare) answer no is unambiguous, meaning that John is not coming. -

Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 92 (2014) 1–32 ! 2

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINAVIAN SYNTAX 92 Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian 1–32 Katarina Lundin An unexpected gap with unexpected restrictions 33–57 Dennis Ott Controlling for movement: Reply to Wood (2012) 58–65 Halldór Ármann Sigur!sson About pronouns 65–98 June 2014 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax ISSN: 1100-097x Johan Brandtler ed. Centre for Languages and Literature Box 201 S-221 00 Lund, Sweden Preface: Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax is an electronic publication for current articles relating to the study of Scandinavian syntax. The articles appearing herein are previously unpublished reports of ongoing research activities and may subsequently appear, revised or unrevised, in other publications. The WPSS homepage: http://project.sol.lu.se/grimm/working-papers-in-scandinavian-syntax/ The 93rd volume of WPSS will be published in December 2014. Papers intended for publication should be submitted no later than October 15, 2014. Contact: Johan Brandtler, editor [email protected]! Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian* Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl University of Gothenburg Abstract We report on a study of preposed object pronouns using the Scandinavian Dialect Corpus. In other Germanic languages, e.g. Dutch and German, preposing of un- stressed object pronouns is restricted, compared with subject pronouns. In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, we find several examples of preposed pronouns, ranging from completely unstressed to emphatically stressed pronouns. We have investi- gated the type of relation between the anaphoric pronoun and its antecedent and found that the most common pattern is rheme-topic chaining followed by topic- topic chaining and left dislocation with preposing. -

Negation and Polarity: an Introduction

Nat Lang Linguist Theory (2010) 28: 771–786 DOI 10.1007/s11049-010-9114-0 Negation and polarity: an introduction Doris Penka · Hedde Zeijlstra Accepted: 9 September 2010 / Published online: 26 November 2010 © The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This introduction addresses some key issues and questions in the study of negation and polarity. Focussing on negative polarity and negative indefinites, it summarizes research trends and results. Special attention is paid to the issues of syn- chronic variation and diachronic change in the realm of negative polarity items, which figure prominently in the articles and commentaries contained in this special issue. Keywords Negative polarity · Negative indefinites · n-words · Negative concord · Synchronic variation · Diachronic change 1 Background This special issue takes its origin in the workshop on negation and polarity (Neg- Pol07) that was held at the University of Tübingen in March 2007. The workshop was hosted by the Collaborative Research Centre 441 “Linguistic Data Structures” and funded by the German Research Council (DFG). Its aim was to bring together researchers working on theoretical aspects of negation and polarity items as well as the empirical basis surrounding these phenomena. One of the reasons to organize this workshop, and to put together this special is- sue, is that after several decades of generative research it is now generally felt that quite some progress has been made in understanding the general mechanics and mo- tivations behind negation and polarity items. At the same time, it becomes more and D. Penka () Zukunftskolleg and Department of Linguistics, University of Konstanz, Box 216, 78457 Konstanz, Germany e-mail: [email protected] H. -

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure Seminar The verb phrase and the syntax-semantics interface , Andrew McIntyre 1 Introduction 1.1 Some basic concepts Part of the knowledge we have about certain linguistic expressions is that they must or may appear with certain other expressions (their arguments ) in order to be interpreted semantically and in order to produce a syntactically well-formed phrase/sentence. (1) John put the book near the door put takes John, the book and near the door as arguments near takes the door and arguably the book as arguments (2) Fred’s reliance on Mary reliance takes on Mary and Fred as arguments (3) John is fond of his stamp collection fond takes his stamp collection and John as arguments An expression taking an argument is called a predicate in modern & philosophical terminology (distinguish from old terminology where predicate = verb phrase). An argument can itself be a predicate (4) Gertrude got angry (in some theories, angry is an argument of get , and Gertrude is an argument of both get and angry ) Some linguists say that arguments can be shared by two predicates, e.g. in (1) the book might be taken to be an argument of both put and near . Argument structure (valency) : the (study of) the arguments taken by expressions. In syntax, we say a predicate (e.g. a verb) has, takes, subcategorises for, selects this or that (or so-and-so many) argument(s). You cannot say you know a word unless you know its argument structure. A word’s argument structure must be mentioned in its lexical entry (=the information associated with the word in the mental lexicon , i.e. -

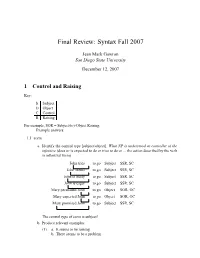

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown. -

1 the Thematic Phase and the Architecture of Grammar Julia Horvath and Tal Siloni 1. Introduction This Paper Directly Addresses

The Thematic Phase and the Architecture of Grammar Julia Horvath and Tal Siloni 1. Introduction This paper directly addresses the controversy around the division of labor between the lexicon and syntax. The last decade has seen a centralization of the operational load in the syntactic component. Prevalent trends in syntactic theory form predicates syntactically by the merger of various heads that compose the event and introduce arguments. The traditional lexicon is reduced to non-computational lists of minimal building blocks (Borer 2005, Marantz 1997, Ramchand 2008, Pylkkänen 2008, among others). The Theta System (Reinhart 2002, this volume), in contrast, assumes that the lexicon is an active component of the grammar, containing information about events and their participants, and allowing the application of valence changing operations. Although Reinhart's work does not explicitly discuss the controversy around the division of labor between these components of grammar, it does provide support for the operational role of the lexicon. Additional evidence in favor of this direction is offered in works such as Horvath and Siloni (2008), Horvath and Siloni (2009), Horvath and Siloni (2011), Hron (2011), Marelj (2004), Meltzer (2011), Reinhart and Siloni (2005), Siloni (2002, 2008, 2012), among others. This paper examines the background and reasons for the rise of anti-lexicalist views of grammar, and undertakes a comparative assessment of these two distinct approaches to the architecture of grammar. Section 2 starts with a historical survey of the developments that led linguists to transfer functions previously attributed to the lexical component to the syntax. Section 3 shows that two major empirical difficulties regarding argument realization that seemed to favor the transfer, can in fact be handled under an active lexicon approach. -

(In)Definiteness, Polarity, and the Role of Wh-Morphology in Free Choice

Journal of Semantics 23: 135–183 doi:10.1093/jos/ffl001 Advance Access publication April 4, 2006 (In)Definiteness, Polarity, and the Role of wh-morphology in Free Choice ANASTASIA GIANNAKIDOU University of Chicago LISA LAI-SHEN CHENG Leiden University Abstract In this paper we reconsider the issue of free choice and the role of the wh- morphology employed in it. We show that the property of being an interrogative wh- word alone is not sufficient for free choice, and that semantic and sometimes even morphological definiteness is a pre-requisite for some free choice items (FCIs) in certain languages, e.g. in Greek and Mandarin Chinese. We propose a theory that explains the polarity behaviour of FCIs cross-linguistically, and allows indefinite (Giannakidou 2001) as well as definite-like FCIs. The difference is manifested as a lexical distinction in English between any (indefinite) and wh-ever (definite); in Greek it appears as a choice between a FCI nominal modifier (taking an NP argument), which illustrates the indefinite option, and a FC free relative illustrating the definite one. We provide a compositional analysis of Greek FCIs in both incarnations, and derive in a parallel manner the Chinese FCIs. Here the definite versus indefinite alternation is manifested in the presence or absence of dou , which we take to express the maximality operator. It is thus shown that what we see in the morphology of FCIs in Greek is reflected in syntax in Chinese. Our analysis has important consequences for the class of so-called wh- indeterminates. In the context of current proposals, free choiceness is taken to come routinely from interrogative semantics, and wh-indeterminates are treated as question words which can freely become FCIs (Kratzer and Shimoyama 2002). -

Negative Polarity

Negative Polarity Vincent Homer June 3, 2019 Final draft. To appear in Blackwell Companion to Semantics, Lisa Matthewson, C´ecile Meier, Hotze Rullman & Thomas Ede Zimmermann (eds.), Wiley. Abstract Negative Polarity Items (NPIs), for example the indefinites any, kanenas (in Greek), quoi que ce soit (in French), minimizers (e.g. lift a finger), the adverb yet, etc., have a limited distribution; they appear to stand in a licensing relation- ship to other expressions, e.g. negation, in the same sentence. This chapter offers an overview of some of the empirical challenges and theoretical issues raised by NPIs. It retraces a line of research (initiated by Klima (1964) and Ladusaw (1979, 1980b)) which started out as an investigation of the right ‘licensing condition(s)’ of NPIs: it sought to characterize licensing operators and used some semantic prop- erty (affectivity, downward-entailingness and variants thereof, or nonveridicality) to do so. It gradually shifted to exploring the very sources of polarity sensitivity: current theories no longer view NPIs as being in ‘need’ of licensing, and instead hold that their contribution to meaning leads to semantic or pragmatic deviance in certain environments, from which they are thus barred. We first present the so- called Fauconnier-Ladusaw approach to NPI licensing, and its licensing condition based on the notion of downward-entailingness. This condition proves to be both too strong and too weak, as argued by Linebarger (1980, 1987, 1991): it is too strong because NPIs can be licensed in the absence of a downward-entailing op- erator, and it is too weak, in view of intervention effects caused by certain scope- taking elements.