Feature Clusters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory

1 The Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory 1. Introduction This chapter reviews some representative examples of scopal dependency and focuses on the issue of how the scope of quantifiers is determined. In particular, we will ask to what extent independently motivated syntactic considerations decide, delimit, or interact with scope interpretation. Many of the theories to be reviewed postulate a level of representation called Logical Form (LF). Originally, this level was invented for the purpose of determining quantifier scope. In current Minimalist theory, all output conditions (the theta-criterion, the case filter, subjacency, binding theory, etc.) are checked at LF. Thus, the study of LF is enormously broader than the study of the syntax of scope. The present chapter will not attempt to cover this broader topic. 1.1 Scope relations We are going to take the following definition as a point of departure: (1) The scope of an operator is the domain within which it has the ability to affect the interpretation of other expressions. Some uncontroversial examples of an operator having scope over an expression and affecting some aspect of its interpretation are as follows: Quantifier -- quantifier Quantifier -- pronoun Quantifier -- negative polarity item (NPI) Examples (2a,b) each have a reading on which every boy affects the interpretation of a planet by inducing referential variation: the planets can vary with the boys. In (2c), the teachers cannot vary with the boys. (2) a. Every boy named a planet. `for every boy, there is a possibly different planet that he named' b. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Principles and Parameters Set out from Europe

Principles and Parameters Set Out from Europe Mark Baker MIT Linguistics 50th Anniversary, 9 December 2011 1. The Opportunity Afforded (1980-1995) The conception of universal principles plus finite discrete parameters of variation offered: The hope and challenge of simultaneously doing justice to both the similarities and the differences among languages. The discovery and expectation of patterns in crosslinguistic variation. These were first presented with respect to “medium- sized” differences in European languages: The subjacency parameter (Rizzi, 1982) The pro-drop parameter (Chomsky, 1981; Kayne, 1984; Rizzi, 1982) They were then perhaps extended to the largest differences among languages around the world: The configurationality parameter(s) (Hale, 1983) “The more languages differ, the more they are the same” Example 1: Mohawk (Baker, 1988, 1991, 1996) Mohawk seems nonconfigurational, with no “syntactic” evidence of a VP containing the object and not the subject: (1) a. Sak wa-ha-hninu-’ ne ka-nakt-a’. Sak FACT-3mS-buy-PUNC NE 3n-bed-NSF b. Sak kanakta wahahninu’ c. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ ne Sak d. Kanakta’ Sak wahahninu’ e. Wahahninu’ ne Sak ne kanakta’ f. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ ne Sak g. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ h. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ i. Sak wahahninu’ j. Wahahninu’ ne Sak k. Wahahninu. All: ‘Sak/he bought a bed/it.’ There are also no differences between subject and object in binding (Condition C, neither c- commands the other) or wh-extraction (both are islands, no “subject condition”) (Baker 1992) Mohawk is polysynthetic (agreement, noun incorporation, applicative, causative, directionals…): (2) a. Sak wa-ha-nakt-a-hninu-’ Sak FACT-3mS-bed-Ø-buy-PUNC ‘Sak bought the bed.’ 1 b. -

Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 92 (2014) 1–32 ! 2

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINAVIAN SYNTAX 92 Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian 1–32 Katarina Lundin An unexpected gap with unexpected restrictions 33–57 Dennis Ott Controlling for movement: Reply to Wood (2012) 58–65 Halldór Ármann Sigur!sson About pronouns 65–98 June 2014 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax ISSN: 1100-097x Johan Brandtler ed. Centre for Languages and Literature Box 201 S-221 00 Lund, Sweden Preface: Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax is an electronic publication for current articles relating to the study of Scandinavian syntax. The articles appearing herein are previously unpublished reports of ongoing research activities and may subsequently appear, revised or unrevised, in other publications. The WPSS homepage: http://project.sol.lu.se/grimm/working-papers-in-scandinavian-syntax/ The 93rd volume of WPSS will be published in December 2014. Papers intended for publication should be submitted no later than October 15, 2014. Contact: Johan Brandtler, editor [email protected]! Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian* Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl University of Gothenburg Abstract We report on a study of preposed object pronouns using the Scandinavian Dialect Corpus. In other Germanic languages, e.g. Dutch and German, preposing of un- stressed object pronouns is restricted, compared with subject pronouns. In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, we find several examples of preposed pronouns, ranging from completely unstressed to emphatically stressed pronouns. We have investi- gated the type of relation between the anaphoric pronoun and its antecedent and found that the most common pattern is rheme-topic chaining followed by topic- topic chaining and left dislocation with preposing. -

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure Seminar The verb phrase and the syntax-semantics interface , Andrew McIntyre 1 Introduction 1.1 Some basic concepts Part of the knowledge we have about certain linguistic expressions is that they must or may appear with certain other expressions (their arguments ) in order to be interpreted semantically and in order to produce a syntactically well-formed phrase/sentence. (1) John put the book near the door put takes John, the book and near the door as arguments near takes the door and arguably the book as arguments (2) Fred’s reliance on Mary reliance takes on Mary and Fred as arguments (3) John is fond of his stamp collection fond takes his stamp collection and John as arguments An expression taking an argument is called a predicate in modern & philosophical terminology (distinguish from old terminology where predicate = verb phrase). An argument can itself be a predicate (4) Gertrude got angry (in some theories, angry is an argument of get , and Gertrude is an argument of both get and angry ) Some linguists say that arguments can be shared by two predicates, e.g. in (1) the book might be taken to be an argument of both put and near . Argument structure (valency) : the (study of) the arguments taken by expressions. In syntax, we say a predicate (e.g. a verb) has, takes, subcategorises for, selects this or that (or so-and-so many) argument(s). You cannot say you know a word unless you know its argument structure. A word’s argument structure must be mentioned in its lexical entry (=the information associated with the word in the mental lexicon , i.e. -

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

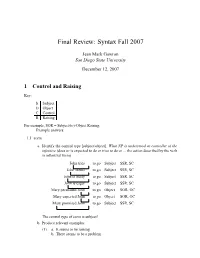

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown. -

1 the Thematic Phase and the Architecture of Grammar Julia Horvath and Tal Siloni 1. Introduction This Paper Directly Addresses

The Thematic Phase and the Architecture of Grammar Julia Horvath and Tal Siloni 1. Introduction This paper directly addresses the controversy around the division of labor between the lexicon and syntax. The last decade has seen a centralization of the operational load in the syntactic component. Prevalent trends in syntactic theory form predicates syntactically by the merger of various heads that compose the event and introduce arguments. The traditional lexicon is reduced to non-computational lists of minimal building blocks (Borer 2005, Marantz 1997, Ramchand 2008, Pylkkänen 2008, among others). The Theta System (Reinhart 2002, this volume), in contrast, assumes that the lexicon is an active component of the grammar, containing information about events and their participants, and allowing the application of valence changing operations. Although Reinhart's work does not explicitly discuss the controversy around the division of labor between these components of grammar, it does provide support for the operational role of the lexicon. Additional evidence in favor of this direction is offered in works such as Horvath and Siloni (2008), Horvath and Siloni (2009), Horvath and Siloni (2011), Hron (2011), Marelj (2004), Meltzer (2011), Reinhart and Siloni (2005), Siloni (2002, 2008, 2012), among others. This paper examines the background and reasons for the rise of anti-lexicalist views of grammar, and undertakes a comparative assessment of these two distinct approaches to the architecture of grammar. Section 2 starts with a historical survey of the developments that led linguists to transfer functions previously attributed to the lexical component to the syntax. Section 3 shows that two major empirical difficulties regarding argument realization that seemed to favor the transfer, can in fact be handled under an active lexicon approach. -

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

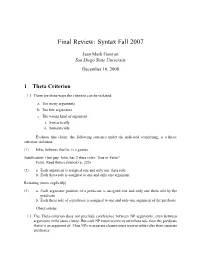

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 10, 2008 1 Theta Criterion 1.1 There are three ways the criterion can be violated: a. Too many arguments b. Too few arguments c. The wrong kind of argument i. Syntactically ii. Semantically Evaluate this claim: the following sentence under the indicated coindexing, is a theta- criterion violation. (1) Johni believes that hei is a genius. Justification: One guy, John, has 2 theta roles. True or False? False. Read theta-criterion (p. 225) (2) a. Each argument is assigned one and only one theta role. b. Each theta role is assigned to one and only one argument. Restating (more explicitly) (3) a. Each argument position of a predicate is assigned one and only one theta role.by the predicate b. Each theta role of a predicate is assigned to one and only one argument of the predicate. Observations: 1.1 The Theta-criterion does not preclude coreference between NP arguments, even between arguments in the same clause. But each NP must receive its own theta role from the predicate that it is an argument of. Thus NPs in separate clauses must receive tehta roles from separate predicates. 1.2 The theta criterion does preclude a predicate from assigning theta roles to NPs other than its OWN subject and complements. For example, a verb may not assign roles to NPs in another clause. 1.3 The theta criterion is not only about verbs. It is about ANY head and its complements and/or subject. (4) a. *Thebookofpoetryofprose b. -

A Minimalist Approach to Argument Structure Heidi Harley, University Of

A Minimalist Approach to Argument Structure Heidi Harley, University of Arizona ([email protected]) Heidi Harley is Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona. Her research focusses primarily on argument structure and morphology, and she has published research in Linguistic Inquiry, Language, Lingua and Studia Linguistica. She has worked on English, Japanese, Irish, Icelanic, Italian and Hiaki (Yaqui). Harley/ Theta Theory 2 In the past fifteen years of minimalist investigation, the theory of argument structure and argument structure alternations has undergone some of the most radical changes of any sub- module of the overall theoretical framework, leading to an outpouring of new analyses of argument structure phenomena in an unprecedented range of languages. Most promisingly, several leading researchers considering often unrelated issues have converged on very similar solutions, lending considerable weight to the overall architecture. Details of implementation certainly vary, but the general framework has achieved almost uniform acceptance. In this paper, we will recap some of the many and varied arguments for the new 'split-vP' syntactic architecture which has taken over most of the functions of theta theory in the old Government and Binding framework, and consider how it can account for the central facts of argument structure and argument structure-changing operations. We then review the framework- wide implications of the new approach, which are considerable. 1. Pre-Minimalism θ-Theory In the Government and Binding framework, any predicate was considered to have several types of information specified in its lexical entry. Besides the basic sound/meaning mapping, connecting some dictionary-style notion of meaning with a phonological exponent, information about the syntactic category and syntactic behavior of the predicate (a subcategorization frame) was specified, as well as, most crucially, information about the number and type of arguments required by that predicate—the predicate's θ-grid. -

ED373534.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 373 534 FL 022 094 AUTHOR Bodomo, Adams B. TITLE Complex Predicates and Event Structure: An Integrated Analysis of Serial Verb Constructions in the Mabia Languages of West Africa. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 20. INSTITUTION Trondheim Univ. (Norway). Dept. of Linguistics. REPORT NO ISSN-0802-3956 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 148p.; Thesis, University of Trondheim, Norway. Map on page 110 may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Undetermined (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Languages; Foreign Countries; *Grammar; *Language Patterns; Language Research; Language Variation; *Semantics; Structural Analysis (Linguistics); *Syntax; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Verbs IDENTIFIERS Africa (West); Dagari ABSTRACT An integrated analysis of the syntax and semantics of serial verb constructions (SVCs) in a group of West African languages is presented. With data from Dagadre and closest relatives, a structural definition for SVCs is developed (two or more lexical verbs that share grammatical categories within a clause), establishing SVCs as complex predicates. Based on syntactic theories, a formal phrase structure is adapted forrepresentation of SVCs, interpreting each as a product of a series of VP adjunctions. Within this new, non-derivational, pro-expansionary approach to grammar, several principles are developed to license grammatical information flow and verbal ordering priority. Based on semantic theories, a functional account of SVCs is developed: that the actions represented by the verbs in the SVC together express a single, complex event. A new model of e. -ant structure for allconstructional transitions is proposed, and it is illustrated how two types of these transitions, West African SVCs and Scandinavian small clause constructions(SCCs), conform to this proposed event structure. -

Full Page Photo

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 4 No. 4; July 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Establishing the Thematic Structure and Investigating the most Prominent Theta Roles Used in Sindhi Language Zahid Ali Veesar (Corresponding author) Faculty of Linguistics, University of Malaya, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Kais Amir Kadhim Faculty of Linguistics, University of Malaya, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Sridevi Sriniwass Faculty of Linguistics, University of Malaya, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Received: 07-12- 2014 Accepted: 21-02- 2015 Advance Access Published: February 2015 Published: 01-07- 2015 doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.4p.216 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.4p.216 Abstract This study focuses on the thematic structure of the Sindhi verbs to find theta roles in the Sindhi language. The study tries to answer the research questions; “What are the thematic structures of Sindhi verbs?” and “What are the prominent theta roles in the Sindhi language?” It examines the argument/thematic structure of Sindhi verbs and also finds the theta roles assigned by the Sindhi verbs to their arguments along with the most prominent theta roles used in the Sindhi language. The data come from the two interviews taken from two young native Sindhi speakers, which consist of 2 hours conversation having 1,669 sentences in natural spoken version of the Sindhi language. Towards the end, it has been found that the Sindhi language has certain theta roles which are assigned by the verbs to their arguments in sentences. -

6. Infinitives

13-15 February 2 •Overview of the different types of infinitives. •Tense inside infinitives…yes, really. •They’re not all CPs! (a look at English, Icelandic, Hindi-Urdu) •Exceptional Case Marking vs Raising to Object. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery •Can PRO get Case? Another Look at Icelandic. 1. Most citizens understand the Constitution of the United States to enumerate certain fundamental rights. 2. What do most citizens understand the Constitution of the United States to enumerate? 3. *Most citizens understand what the Constitution of the United 3 States to enumerate. 4. Most citizens understand what the Constitution of the United States enumerates. 5. Many people told the founders what to enumerate in the Constitution of the United States. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery Ø The semantics and morphology of infinitives interact with 4 some of the most fundamental aspects of syntactic theory – e.g, the Theta Criterion and the Case Filter. Ø The subject has not overtly realized in many infinitives and the verb does not show agreement morphology in many languages. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery § Raising: Subject of the main clause is semantically related to the verb in the embedded clause, but not to the verb in the main clause. § Verb in the main clause does not have a theta role for a subject. § Control: Subject/object of the main clause is semantically related to the verbs in both the main clause and the embedded clause. § Both the main and embedded clause verbs have theta roles for subjects. § Exceptional Case Marking (ECM): DP that “looks” like the object of the main clause is actually semantically related to the verb of the embedded clause.