An Analysis of Theta Role of Verbs in Hausa Ali Umar Muhammad Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirments F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Clusters

Chapter 2 Feature Clusters 1. Introduction The goal of this Chapter is to address certain issues that pertain to the properties of feature clusters and the rules that govern their co-occurrences. Feature clusters come as fully specified (e.g. [+c+m] associated with people in (1a)) and ‘underspecified’ (e.g. [-c] associated with acquaintances in (1a)). Such partitioning of feature clusters raises the question of the implications of notions such as ‘underspecified’ and ‘fully specified’ in syntactic and semantic terms. The sharp contrast between the grammaticality of the middle derivation in (1b) and ungrammaticality of (1c) takes the investigation into rules that regulate the co-realization of feature clusters of the base-verb (1a). Another issue that is discussed in this Chapter is the status of arguments versus adjuncts in the Theta System. This topic is also of importance for tackling the issue of middles in Chapter 4 since – intriguingly enough – whereas (1c) is not an acceptable middle derivation in English, (1d) is. (1a) People[+c+m] don’t send expensive presents to acquaintances[-c] (1b) Expensive presents send easily. (1c) *Expensive presents send acquaintances easily. (1d) Expensive presents do not send easily to foreign countries. In section 2 of this Chapter, the properties of feature clusters with respect to syntax and semantics are examined. Section 3 sets the background for Section 4 by addressing the issue of conditions on thematic roles that have been assumed in the literature. Section 4 deals with conditions that govern the co-occurrences of feature clusters in the Theta System. The discussion in section 4 will necessitate the discussion of adjunct versus argument status of certain phrases. -

1 the Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory

1 The Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory 1. Introduction This chapter reviews some representative examples of scopal dependency and focuses on the issue of how the scope of quantifiers is determined. In particular, we will ask to what extent independently motivated syntactic considerations decide, delimit, or interact with scope interpretation. Many of the theories to be reviewed postulate a level of representation called Logical Form (LF). Originally, this level was invented for the purpose of determining quantifier scope. In current Minimalist theory, all output conditions (the theta-criterion, the case filter, subjacency, binding theory, etc.) are checked at LF. Thus, the study of LF is enormously broader than the study of the syntax of scope. The present chapter will not attempt to cover this broader topic. 1.1 Scope relations We are going to take the following definition as a point of departure: (1) The scope of an operator is the domain within which it has the ability to affect the interpretation of other expressions. Some uncontroversial examples of an operator having scope over an expression and affecting some aspect of its interpretation are as follows: Quantifier -- quantifier Quantifier -- pronoun Quantifier -- negative polarity item (NPI) Examples (2a,b) each have a reading on which every boy affects the interpretation of a planet by inducing referential variation: the planets can vary with the boys. In (2c), the teachers cannot vary with the boys. (2) a. Every boy named a planet. `for every boy, there is a possibly different planet that he named' b. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Principles and Parameters Set out from Europe

Principles and Parameters Set Out from Europe Mark Baker MIT Linguistics 50th Anniversary, 9 December 2011 1. The Opportunity Afforded (1980-1995) The conception of universal principles plus finite discrete parameters of variation offered: The hope and challenge of simultaneously doing justice to both the similarities and the differences among languages. The discovery and expectation of patterns in crosslinguistic variation. These were first presented with respect to “medium- sized” differences in European languages: The subjacency parameter (Rizzi, 1982) The pro-drop parameter (Chomsky, 1981; Kayne, 1984; Rizzi, 1982) They were then perhaps extended to the largest differences among languages around the world: The configurationality parameter(s) (Hale, 1983) “The more languages differ, the more they are the same” Example 1: Mohawk (Baker, 1988, 1991, 1996) Mohawk seems nonconfigurational, with no “syntactic” evidence of a VP containing the object and not the subject: (1) a. Sak wa-ha-hninu-’ ne ka-nakt-a’. Sak FACT-3mS-buy-PUNC NE 3n-bed-NSF b. Sak kanakta wahahninu’ c. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ ne Sak d. Kanakta’ Sak wahahninu’ e. Wahahninu’ ne Sak ne kanakta’ f. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ ne Sak g. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ h. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ i. Sak wahahninu’ j. Wahahninu’ ne Sak k. Wahahninu. All: ‘Sak/he bought a bed/it.’ There are also no differences between subject and object in binding (Condition C, neither c- commands the other) or wh-extraction (both are islands, no “subject condition”) (Baker 1992) Mohawk is polysynthetic (agreement, noun incorporation, applicative, causative, directionals…): (2) a. Sak wa-ha-nakt-a-hninu-’ Sak FACT-3mS-bed-Ø-buy-PUNC ‘Sak bought the bed.’ 1 b. -

Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 92 (2014) 1–32 ! 2

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINAVIAN SYNTAX 92 Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian 1–32 Katarina Lundin An unexpected gap with unexpected restrictions 33–57 Dennis Ott Controlling for movement: Reply to Wood (2012) 58–65 Halldór Ármann Sigur!sson About pronouns 65–98 June 2014 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax ISSN: 1100-097x Johan Brandtler ed. Centre for Languages and Literature Box 201 S-221 00 Lund, Sweden Preface: Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax is an electronic publication for current articles relating to the study of Scandinavian syntax. The articles appearing herein are previously unpublished reports of ongoing research activities and may subsequently appear, revised or unrevised, in other publications. The WPSS homepage: http://project.sol.lu.se/grimm/working-papers-in-scandinavian-syntax/ The 93rd volume of WPSS will be published in December 2014. Papers intended for publication should be submitted no later than October 15, 2014. Contact: Johan Brandtler, editor [email protected]! Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian* Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl University of Gothenburg Abstract We report on a study of preposed object pronouns using the Scandinavian Dialect Corpus. In other Germanic languages, e.g. Dutch and German, preposing of un- stressed object pronouns is restricted, compared with subject pronouns. In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, we find several examples of preposed pronouns, ranging from completely unstressed to emphatically stressed pronouns. We have investi- gated the type of relation between the anaphoric pronoun and its antecedent and found that the most common pattern is rheme-topic chaining followed by topic- topic chaining and left dislocation with preposing. -

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure Seminar The verb phrase and the syntax-semantics interface , Andrew McIntyre 1 Introduction 1.1 Some basic concepts Part of the knowledge we have about certain linguistic expressions is that they must or may appear with certain other expressions (their arguments ) in order to be interpreted semantically and in order to produce a syntactically well-formed phrase/sentence. (1) John put the book near the door put takes John, the book and near the door as arguments near takes the door and arguably the book as arguments (2) Fred’s reliance on Mary reliance takes on Mary and Fred as arguments (3) John is fond of his stamp collection fond takes his stamp collection and John as arguments An expression taking an argument is called a predicate in modern & philosophical terminology (distinguish from old terminology where predicate = verb phrase). An argument can itself be a predicate (4) Gertrude got angry (in some theories, angry is an argument of get , and Gertrude is an argument of both get and angry ) Some linguists say that arguments can be shared by two predicates, e.g. in (1) the book might be taken to be an argument of both put and near . Argument structure (valency) : the (study of) the arguments taken by expressions. In syntax, we say a predicate (e.g. a verb) has, takes, subcategorises for, selects this or that (or so-and-so many) argument(s). You cannot say you know a word unless you know its argument structure. A word’s argument structure must be mentioned in its lexical entry (=the information associated with the word in the mental lexicon , i.e. -

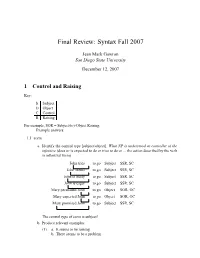

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 12, 2007 1 Control and Raising Key: S Subject O Object C Control R Raising For example, SOR = Subject(to)-Object Raising. Example answers: 1.1 seem a. Identify the control type [subject/object]. What NP is understood as controller of the infinitive (does or is expected to do or tries to do or ... the action described by the verb in infinitival form) John tries to go Subject SSR, SC John seems to go Subject SSR, SC John is likely to go Subject SSR, SC John is eager to go Subject SSR, SC Mary persuaded John to go Object SOR, OC Mary expected John to go Object SOR, OC Mary promised John to go Subject SSR, SC The control type of seem is subject! b. Produce relevant examples: (1) a. Itseemstoberaining b. There seems to be a problem c. The chips seems to be down. d. It seems to be obvious that John is a fool. e. The police seem to have caught the burglar. f. The burglar seems to have been caught by the police. c. Example construction i. Construct embedded clause: (a) itrains. Simpleexample;dummysubject * John rains Testing dummy subjecthood ittorain Putintoinfinitivalform ii. Embed (a) ∆ seem [CP it to rain] Embed under seem [ctd.] it seem [CP t torain] Moveit— it seems [CP t to rain] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) d. Other examples (b) itisraining. Alternativeexample;dummysubject *Johnisraining Testingdummysubjecthood ittoberaining Putintoinfinitivalform ∆ seem [CP it to be raining] Embed under seem it seem [CP t toberaining] Moveit— it seems [CP t to be raining] Add tense, agreement (to main verb) (c) Thechipsaredown. -

1 the Thematic Phase and the Architecture of Grammar Julia Horvath and Tal Siloni 1. Introduction This Paper Directly Addresses

The Thematic Phase and the Architecture of Grammar Julia Horvath and Tal Siloni 1. Introduction This paper directly addresses the controversy around the division of labor between the lexicon and syntax. The last decade has seen a centralization of the operational load in the syntactic component. Prevalent trends in syntactic theory form predicates syntactically by the merger of various heads that compose the event and introduce arguments. The traditional lexicon is reduced to non-computational lists of minimal building blocks (Borer 2005, Marantz 1997, Ramchand 2008, Pylkkänen 2008, among others). The Theta System (Reinhart 2002, this volume), in contrast, assumes that the lexicon is an active component of the grammar, containing information about events and their participants, and allowing the application of valence changing operations. Although Reinhart's work does not explicitly discuss the controversy around the division of labor between these components of grammar, it does provide support for the operational role of the lexicon. Additional evidence in favor of this direction is offered in works such as Horvath and Siloni (2008), Horvath and Siloni (2009), Horvath and Siloni (2011), Hron (2011), Marelj (2004), Meltzer (2011), Reinhart and Siloni (2005), Siloni (2002, 2008, 2012), among others. This paper examines the background and reasons for the rise of anti-lexicalist views of grammar, and undertakes a comparative assessment of these two distinct approaches to the architecture of grammar. Section 2 starts with a historical survey of the developments that led linguists to transfer functions previously attributed to the lexical component to the syntax. Section 3 shows that two major empirical difficulties regarding argument realization that seemed to favor the transfer, can in fact be handled under an active lexicon approach. -

African Music Vol 6 No 3(Seb)

16 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY OF AFRICAN MUSIC NOTES ON MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AMONG THE FULANI OF DIAMARE (NORTH CAMEROON) by VEIT ERLMANN I. Introduction The Central Sudan, enclosing the northern parts of the Cameroons and Nigeria, South-Niger and parte of Chad, has been viewed by different scholars under various aspects as one coherent area sharing certain cultural traits. Some of these are due to the impact of Islam during the past 500 years: town-culture, feudal social hierarchy, class distinctions, and literacy. The impact of Islam is strongest among the Hausa, Fulani1, Kanembu, Kanuri, Manga, Kotoko, and Shoa Arabs. For more than five centuries there has been a constant flow of economic, social and cultural exchange between these groups which also left its traces in the musical culture. Ethnomusicology does not seem to have focused very much on this area2, the Hausa being in fact the only ethnic group whose musical culture can be said to have been thoroughly explored3. Kanuri, Manga, and Shoa music are almost unknown, while the musical cultures of the Kanembu and Kotoko received at least some attention in few articles and casual record notes4. As for the Fulani of Cameroon some records exist 5, but no written information on their music is available. Hence, this paper attempts to give a general account of the musical organology of the Fulani in North Cameroon and to contribute to the completion of ethnomusicological knowledge in this area6 through the presentation of new material and the basic facts of Fulani organology (names of instruments and their parts, social usage, history). -

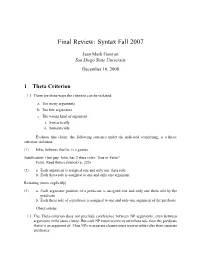

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 10, 2008 1 Theta Criterion 1.1 There are three ways the criterion can be violated: a. Too many arguments b. Too few arguments c. The wrong kind of argument i. Syntactically ii. Semantically Evaluate this claim: the following sentence under the indicated coindexing, is a theta- criterion violation. (1) Johni believes that hei is a genius. Justification: One guy, John, has 2 theta roles. True or False? False. Read theta-criterion (p. 225) (2) a. Each argument is assigned one and only one theta role. b. Each theta role is assigned to one and only one argument. Restating (more explicitly) (3) a. Each argument position of a predicate is assigned one and only one theta role.by the predicate b. Each theta role of a predicate is assigned to one and only one argument of the predicate. Observations: 1.1 The Theta-criterion does not preclude coreference between NP arguments, even between arguments in the same clause. But each NP must receive its own theta role from the predicate that it is an argument of. Thus NPs in separate clauses must receive tehta roles from separate predicates. 1.2 The theta criterion does preclude a predicate from assigning theta roles to NPs other than its OWN subject and complements. For example, a verb may not assign roles to NPs in another clause. 1.3 The theta criterion is not only about verbs. It is about ANY head and its complements and/or subject. (4) a. *Thebookofpoetryofprose b. -

Muhammad, Sharu

FEMALE PRAISE SINGERS IN NUPELAND: A FORMALIST STUDY OF FATIMA LOLO BIDA AND HAWAWU KULU LAFIAGI’S SELECTED SONGS BY MUHAMMAD, SHARU DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES, FACULTY OF ARTS, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA. NOVEMBER, 2016 i FEMALE PRAISE SINGERS IN NUPELAND: A FORMALIST STUDY OF FATIMA LOLO BIDA AND HAWAWU KULU LAFIAGI’S SELECTED SONGS BY MUHAMMAD, SHARU BA (1992) UDUS, MA (2008) ABU (Ph. D/ARTS/1986/2011–2012) NOVEMBER, 2016 ii FEMALE PRAISE SINGERS IN NUPELAND: A FORMALIST STUDY OF FATIMA LOLO BIDA AND HAWAWU KULU LAFIAGI’S SELECTED SONGS MUHAMMAD, SHARU (Ph. D/ARTS/1986/2011–2012) A Thesis Presented to the Post Graduate School, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) in English (Literature) Department of English and Literary Studies, Faculty of Arts, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. November, 2016 iii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis has been written by me, and it is a record of my own research work. It has not been submitted in any previous application of a higher degree. All quotations are indicated and the sources of information are suitably acknowledged by means of references. ------------------------------------------- Sharu Muhammad ------------------------------------------ Date iv CERTIFICATION This thesis, entitled “Female Praise Singers in Nupeland: A Formalist Study of Fatima Lolo Bida and Hawawu Kulu Lafiagi‟s Selected Songs” by Sharu Muhammad meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literature of the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. -

A Minimalist Approach to Argument Structure Heidi Harley, University Of

A Minimalist Approach to Argument Structure Heidi Harley, University of Arizona ([email protected]) Heidi Harley is Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona. Her research focusses primarily on argument structure and morphology, and she has published research in Linguistic Inquiry, Language, Lingua and Studia Linguistica. She has worked on English, Japanese, Irish, Icelanic, Italian and Hiaki (Yaqui). Harley/ Theta Theory 2 In the past fifteen years of minimalist investigation, the theory of argument structure and argument structure alternations has undergone some of the most radical changes of any sub- module of the overall theoretical framework, leading to an outpouring of new analyses of argument structure phenomena in an unprecedented range of languages. Most promisingly, several leading researchers considering often unrelated issues have converged on very similar solutions, lending considerable weight to the overall architecture. Details of implementation certainly vary, but the general framework has achieved almost uniform acceptance. In this paper, we will recap some of the many and varied arguments for the new 'split-vP' syntactic architecture which has taken over most of the functions of theta theory in the old Government and Binding framework, and consider how it can account for the central facts of argument structure and argument structure-changing operations. We then review the framework- wide implications of the new approach, which are considerable. 1. Pre-Minimalism θ-Theory In the Government and Binding framework, any predicate was considered to have several types of information specified in its lexical entry. Besides the basic sound/meaning mapping, connecting some dictionary-style notion of meaning with a phonological exponent, information about the syntactic category and syntactic behavior of the predicate (a subcategorization frame) was specified, as well as, most crucially, information about the number and type of arguments required by that predicate—the predicate's θ-grid.