African Music Vol 6 No 3(Seb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

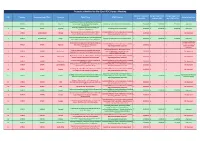

Projects Submitted to the 62Nd IPDC Bureau Meeting

Projects submitted to the 62nd IPDC Bureau Meeting Amount requested Budget approved Budget approved NO. Region Implementing Office Country Title / Titre IPDC Priority Bureau Decision from IPDC without PSC with PSC of 7% Strenghtening Kakaki community radio for improved 1 AFRICA ABUJA Nigeria service delivery and enhanced community Supporting media pluralism and independence $ 20,070.00 $ 20,320.00 $ 21,742.40 Approved participation Promoting Media Development and Safety of 2 AFRICA ACCRA Regional Promoting Safety of Journalists $ 34,500.00 $ 23,000.00 $ 24,610.00 Approved Journalists in West Africa Building journalism educators´capacity of Jimma Capacity building for media professionals, including 3 AFRICA ADDIS ABABA Ethiopia $ 16,749.00 $ - $ - Not Approved University through audio visual skill training improving journalism education Renforcement des capacités de la radio citoyenne des 4 AFRICA BRAZZAVILLE Congo Supporting media pluralism and independence $ 20,690.00 $ 18,000.00 $ 19,260.00 Approved jeunes pour la promotion des valeurs citoyennes Not approved (To be Renforcement de capacités et de moyens du Réseau Capacity building for media professionals, including resubmitted next year 5 AFRICA DAKAR Regional des radios en Afrique de l´Ouest pour $ 19,500.00 $ - $ - improving journalism education with an improved l´environnement proposal) Countering hate speech, promoting conflict- Projet de renforcement des capacités des femmes 6 AFRICA DAKAR Burkina Faso sensitive journalism or promoting cross- $ 20,000.00 $ - $ - Not Approved animatrices -

1 Chapter Three Historical

University of Pretoria etd, Adeogun A O (2006) CHAPTER THREE HISTORICAL-CULTURAL BACKCLOTH OF MUSIC EDUCATION IN NIGERIA This chapter traces the developments of music education in the precolonial Nigeria. It is aimed at giving a social, cultural and historical background of the country – Nigeria in the context of music education. It describes the indigenous African music education system that has been in existence for centuries before the arrival of Islam and Christianity - two important religions, which have influenced Nigerian music education in no small measure. Although the title of this thesis indicates 1842-2001, it is deemed expedient, for the purposes of historical background, especially in the northern part of Nigeria, to dwell contextually on the earlier history of Islamic conquest of the Hausaland, which introduced the dominant musical traditions and education that are often mistaken to be indigenous Hausa/northern Nigeria. The Islamic music education system is dealt with in Chapter four. 3.0 Background - Nigeria Nigeria, the primarily focus of this study, is a modern nation situated on the Western Coast of Africa, on the shores of the Gulf of Guinea which includes the Bights of Benin and Biafra (Bonny) along the Atlantic Coast. Entirely within the tropics, it lies between the latitude of 40, and 140 North and longitude 20 501 and 140 200 East of the Equator. It is bordered on the west, north (northwest and northeast) and east by the francophone countries of Benin, Niger and Chad and Cameroun respectively, and is washed by the Atlantic Ocean, in the south for about 313 kilometres. -

An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria Agatha Onyinye Holland WVU, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Africana Studies Commons, African Languages and Societies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Agatha Onyinye, "An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7917. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7917 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria Agatha Holland Research Document submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University -

Muhammad, Sharu

FEMALE PRAISE SINGERS IN NUPELAND: A FORMALIST STUDY OF FATIMA LOLO BIDA AND HAWAWU KULU LAFIAGI’S SELECTED SONGS BY MUHAMMAD, SHARU DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES, FACULTY OF ARTS, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA. NOVEMBER, 2016 i FEMALE PRAISE SINGERS IN NUPELAND: A FORMALIST STUDY OF FATIMA LOLO BIDA AND HAWAWU KULU LAFIAGI’S SELECTED SONGS BY MUHAMMAD, SHARU BA (1992) UDUS, MA (2008) ABU (Ph. D/ARTS/1986/2011–2012) NOVEMBER, 2016 ii FEMALE PRAISE SINGERS IN NUPELAND: A FORMALIST STUDY OF FATIMA LOLO BIDA AND HAWAWU KULU LAFIAGI’S SELECTED SONGS MUHAMMAD, SHARU (Ph. D/ARTS/1986/2011–2012) A Thesis Presented to the Post Graduate School, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) in English (Literature) Department of English and Literary Studies, Faculty of Arts, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. November, 2016 iii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis has been written by me, and it is a record of my own research work. It has not been submitted in any previous application of a higher degree. All quotations are indicated and the sources of information are suitably acknowledged by means of references. ------------------------------------------- Sharu Muhammad ------------------------------------------ Date iv CERTIFICATION This thesis, entitled “Female Praise Singers in Nupeland: A Formalist Study of Fatima Lolo Bida and Hawawu Kulu Lafiagi‟s Selected Songs” by Sharu Muhammad meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literature of the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. -

P a R L I a M E N T a R I a N S F O R G L O B a L a C T I

06 P a r l i a m e n t a r i a n s f o r G l o b a l A c t i o n PARLIAMENTARY SEMINAR ON HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN WEST AFRICA: THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTARIANS In collaboration with: Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Parliament Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Executive Secretariat Office of Human Trafficking & Child Labor, Federal Republic of Nigeria National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) Women’s Trafficking & Child Labour Eradication Foundation (WOTCLEF) International Labour Organization (ILO) International Organization for Migration (IOM) With the support of The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation The Federal Republic of Nigeria The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) European Commission Joshua Hall, Protea Hotel Abuja, Nigeria February 24-25, 2004 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Members of Parliaments Bénin Dep. Nouhoum Assouman First Rapporteur, ECOWAS Committee on Foreign Affairs, Cooperation, Defense and Security Member, ECOWAS Committee on Environment and Natural Resources Burkina Faso Dep. Nongma Ernest Ouedraogo Member, ECOWAS Committee on Laws, Regulations, Legal and Judicial Affairs - Human Rights and Free Movement of Persons Dep. Cecile Beloum Vice-Chair, ECOWAS Committee on Women and Children’s Rights 211 East 43rd Street, Suite 1604, New York, NY 10017, USA T: 1-212-687-7755 F:1-212-687-8409 E-mail: [email protected] PGA Parliamentary Seminar on Human Trafficking in West Africa Page 2 Cape Verde Dep. Atelano Joao de Henrique Dias da Fonseca Member, ECOWAS Committee on Women and Children’s Rights Côte d’Ivoire Dep. -

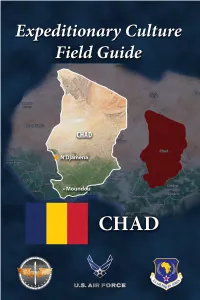

ECFG Chad 2021 Ed1r.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Army flag officer tours Chadian hospital with the facility commander). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Chad, focusing on unique C cultural features of Chadian society had and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo: Traditionally, Chadian girls start covering their heads at a young age, courtesy of CultureGrams, ProQuest). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

Hemispheres Studies on Cultures and Societies Vol. 30, No. 3

Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures Polish Academy of Sciences Hemispheres Studies on Cultures and Societies Vol. 30, No. 3 NIGERIA Wydawnictwo Naukowe ASKON Warszawa 2015 Editor-in-Chief Board of Advisory Editors JERZY ZDANOWSKI GRZEGORZ J. KACZYÑSKI OLA EL KHAWAGA Subject Editor MARIUSZ KRANIEWSKI ABIDA EIJAZ HARRY T. NORRIS English Text Consultant STANIS£AW PI£ASZEWICZ STEPHEN WALLIS EVARISTE N. PODA Secretary MARIA SK£ADANKOWA SABINA BRAKONIECKA MICHA£ TYMOWSKI This edition is prepared, set and published by Wydawnictwo Naukowe ASKON Sp. z o.o. ul. Stawki 3/1, 00193 Warszawa tel./fax: (48) 22 635 99 37 www.askon.waw.pl [email protected] © Copyright by Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 2015 PL ISSN 02398818 ISBN 9788374520874 HEMISPHERES is published quarterly and is indexed in ERIH PLUS, The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, ProQuest Database and Index Copernicus Contents Nkem O k o h, Translation as Validation of Culture: The Example of Chinua Achebe ....................................................................................... 5 Khalid I m a m, Justice, Fairness and the Quest for an Egalitarian Society in Africa: A Reading of Bukar Usmans Select Tales in Taskar Tatsuniyoyi: Littafi na Daya Zuwa na Goma Sha Hudu [A Compendium of Hausa Tales Book One to Fourteen] ....................................................21 Ibrahim Garba Satatima, Hausa Oral Songs as a Cultural Reflexive: A Study on Some Emotional Compositions ................................................33 -

An Analysis of Theta Role of Verbs in Hausa Ali Umar Muhammad Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirments F

AN ANALYSIS OF THETA ROLE OF VERBS IN HAUSA ALI UMAR MUHAMMAD DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE IN MASTER OF LINGUISTICS FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2014 UNIVERSITY MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Ali Umar Muhammad (Passport N0: A04059610) Registration/Matric N0: TGC 120080 Name of Degree: Master of Linguistics Title of Project Paper/ Research Report/ Dissertation/ Thesis (“thi Work”) AN Analysis of Theta Role of Verbs in Hausa Field of Study: Syntax I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am sole author/writer of this work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of marking this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

122 Pment” Ibadan: 88. Parable Logy As A: Koly MUSIC AND

Drama as a Tool for Social Commentary: An Example of Alex Asigbo’s ... MUSIC AND DEMOCRACY: A TALE OF NATURE AND CONTRIVANCE Odiri, Solomon E “Theatre in Nigeria and National Development” African Arts and National Development Sam Ukala ed Ibadan: Chukwuemenam E. Umezinwa Kraft Books, 2006. 251-260. Soyinka Wole: Opera Wonyosi Ibadan: Spectrum Books, 1988. Utoh-Ezeajuh, Tracie. “Dramatizing a People’s History as a Parable Abstract for a Nation in Search of Peace: Alex Asigbo’s Duology as Regarding music and democracy, one is likely to ask: what has Paradigm.” Theatre Experience. Vol 2 No 1. Onitsha: Koly a goldfish in common with the canary? Or what has Athens got to Computer House, 2003. 10-17. do with Jerusalem? In grouping the disciplines according to university curriculum of studies, music is the queen of the arts while democracy as a system of governance has a better footing in the social sciences. Without prejudice to whatever we hold dear concerning these two conceptual entities, this article casts more than a cursory glance at the two, to find out if there are truths that might be of interest while we advance the cause of each. The starting point is to consider the nature of their origins, their purposes and the experiences they nurture. The findings are revealing. Music is as old as man and so, assumes the status of a necessary human good. Democracy as a recent human invention and being fraught with an endemic pursuit of selfish interests of individuals and nations, can, at its best, be a necessary evil. -

The Lunsi Traditional Music of the Frafras in Tamso

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh THE LUNSI TRADITIONAL MUSIC OF THE FRAFRAS IN TAMSO BY EVANS OPPONG (10363983) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY MUSIC DEGREE JULY 2013 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION This is to certify that this thesis is the result of research undertaken by Evans Oppong towards the award of the Master of Philosophy in the department of music, University of Ghana. Signed ……………………………………………………………… Evans Oppong (Student) Supervisors 1. ……………………………………………..………………… Mr. Ken Kafui 2. ………………………………………………………………… Prof. John Collins i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DEDICATION I hereby dedicate this work to Mrs. Scholastica Mensah of Westlink Pharmacy, Tarkwa; who has been a backbone financially and spiritually to me. ii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS He who is appreciative will never forget his creator for successfulness in an endeavor. I am so grateful to God for seeing me through this project work though faced with challenges. I will like to also show appreciation to my supervisors; Professor John Collins and Mr. Ken Kafui, both of the Music Department of the University of Ghana, Legon for pains-takingly going through and putting to shape this work. Thanks are to Mr. Zablong Zachariah Abdullah (African Studies, university of Ghana legon) who allowed himself to be engaged in one-on-one discussion about Lunsi music. I appreciate the time, energy, space and knowledge rendered. Thanks are to Mr. Joseph Abaidu (Tarkwa-Tamso St. -

Online Bibliography of Chadic and Hausa Linguistics

Online Bibliography of Chadic and Hausa Linguistics PAUL NEWMAN Online Bibliography of Chadic and Hausa Linguistics compiled by PAUL NEWMAN 1. INTRODUCTION The Online Bibliography of Chadic and Hausa Linguistics (OBCHL), henceforth the ‘biblio’, is an updated, expanded, and corrected edition of the bibliography published some fifteen years ago by Rüdiger Köppe Verlag (Newman 1996). That biblio was built on valuable earlier works including Hair (1967), Newman (1971), Baldi (1977), R. M. Newman (1979), Awde (1988), and Barreteau (1993). The ensuing years have witnessed an outpouring of new publications on Chadic and Hausa, written by scholars from around the globe, thereby creating the need for a new, up-to-date bibliography. Data gathered for this online edition, which was compiled using EndNote, an excellent and easy to use bibliographic database program, have come from my own library and internet searches as well as from a variety of published sources. Particularly valuable have been the reviews of the earlier bibliography, most notably the detailed review article by Baldi (1997), the Hausa and Chadic entries in the annual Bibliographie Linguistique, compiled over the past dozen years by Dr. Joe McIntyre, and the very useful list of publications found regularly in Méga-Tchad. The enormous capacity afforded by the internet to organize and update large-scale reference works such as bibliographies and dictionaries enables us to present this new online bibliography as a searchable, open access publication. This Version-02 is presented in PDF format only. A goal for the future is to make the biblio available in database format as well. 2. -

West African Music in the Music of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston

West African Music in the Music of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston by Jason John Squinobal Batchelor of Music, Music Education, Berklee College of Music, 2003 Master of Arts, Ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2009 ffh UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jason John Squinobal It was defended on April 14, 2009 and approved by Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department Dr. Akin Euba, Professor, Music Department Dr. Eric Moe, Professor, Music Department Dr. Joseph K. Adjaye, Professor, Africana Studies Dissertation Director: Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department ii Copyright © by Jason John Squinobal 2009 iii West African Music in the Music of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston Jason John Squinobal, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Abstract This Dissertation is a historical study of the cultural, social and musical influences that have led to the use of West African music in the compositions and performance of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston. Many jazz musicians have utilized West African music in their musical compositions. Blakey, Lateef and Weston were not the first musicians to do so, however they were chosen for this dissertation because their experiences, influences, and music clearly illustrate the importance that West African culture has played in the lives of African American jazz musicians. Born during the Harlem Renaissance each of these musicians was influenced by the political views and concepts that predominated African American culture at that time.