1 Chapter Three Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Singer As Priestess

-, ' 11Ie Singer as Priestess: Interviews with Celina Gonzatez and Merceditas Valdes ".:" - , «1',..... .... .. (La Habana, 1993) Ivor Miller Celina Gonzalez: Queen of the Punto Cubano rummer Ivan Ayala) grew up in New York City listening to the music of Celina Gonzalez. * As Da child in the 1960s he was brought to Puerto Rican espiritista ceremonies, where instead of using drums, practitioners would play Celina's records to invoke the spirits. This is one way that Celina's music and the dedication of her followers have blasted through the U.S. embargo against Cuba that has deprived us of some of the planet's most potent music, art and literature for over 32 years. Ivan's experi ence shows the ingenuity of working people in maintaining human connections that are essential to them, in spite of governments that would keep them separate. Hailed as musical royalty in Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, England and in Latin USA, Celina has, until very recently, been kept out of the U.S. n:tarket.2 Cuba has long been a mecca for African-derived religious and musical traditions, and Celina's music taps a deep source. It is at the same time popular and sacred, danceable and political. By using the ancient Spanish dicima song form to sing about the Yoruba deities (orichas), she has become a symbol of Cuban creole (criollo) traditions. A pantheon of orichas are worshipped in the Santeria religion, which is used by practitioners to protect humans from sickness and death, and to open the way for peace, stability, and success. During the 14 month period that I spent in Cuba from 1991-1994, I had often heard Celina's music on the radio, TV, and even at a concert/rally for the Young Communist League (UJC), where the chorus of "Long live Chango'" ("iQueviva Chango!") was chanted by thou Celina Gonzalez (r) and [dania Diaz (l) injront o/Celina's Santa sands of socialist Cuba's "New Men" at the Plaza of the Revolution.3 Celina is a major figure in Cuban music and cultural identity. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

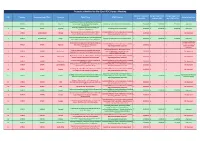

Projects Submitted to the 62Nd IPDC Bureau Meeting

Projects submitted to the 62nd IPDC Bureau Meeting Amount requested Budget approved Budget approved NO. Region Implementing Office Country Title / Titre IPDC Priority Bureau Decision from IPDC without PSC with PSC of 7% Strenghtening Kakaki community radio for improved 1 AFRICA ABUJA Nigeria service delivery and enhanced community Supporting media pluralism and independence $ 20,070.00 $ 20,320.00 $ 21,742.40 Approved participation Promoting Media Development and Safety of 2 AFRICA ACCRA Regional Promoting Safety of Journalists $ 34,500.00 $ 23,000.00 $ 24,610.00 Approved Journalists in West Africa Building journalism educators´capacity of Jimma Capacity building for media professionals, including 3 AFRICA ADDIS ABABA Ethiopia $ 16,749.00 $ - $ - Not Approved University through audio visual skill training improving journalism education Renforcement des capacités de la radio citoyenne des 4 AFRICA BRAZZAVILLE Congo Supporting media pluralism and independence $ 20,690.00 $ 18,000.00 $ 19,260.00 Approved jeunes pour la promotion des valeurs citoyennes Not approved (To be Renforcement de capacités et de moyens du Réseau Capacity building for media professionals, including resubmitted next year 5 AFRICA DAKAR Regional des radios en Afrique de l´Ouest pour $ 19,500.00 $ - $ - improving journalism education with an improved l´environnement proposal) Countering hate speech, promoting conflict- Projet de renforcement des capacités des femmes 6 AFRICA DAKAR Burkina Faso sensitive journalism or promoting cross- $ 20,000.00 $ - $ - Not Approved animatrices -

An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria Agatha Onyinye Holland WVU, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Africana Studies Commons, African Languages and Societies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Agatha Onyinye, "An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7917. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7917 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Appraisal of the Evolution of Western Art Music in Nigeria Agatha Holland Research Document submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University -

African Music Vol 6 No 3(Seb)

16 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY OF AFRICAN MUSIC NOTES ON MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AMONG THE FULANI OF DIAMARE (NORTH CAMEROON) by VEIT ERLMANN I. Introduction The Central Sudan, enclosing the northern parts of the Cameroons and Nigeria, South-Niger and parte of Chad, has been viewed by different scholars under various aspects as one coherent area sharing certain cultural traits. Some of these are due to the impact of Islam during the past 500 years: town-culture, feudal social hierarchy, class distinctions, and literacy. The impact of Islam is strongest among the Hausa, Fulani1, Kanembu, Kanuri, Manga, Kotoko, and Shoa Arabs. For more than five centuries there has been a constant flow of economic, social and cultural exchange between these groups which also left its traces in the musical culture. Ethnomusicology does not seem to have focused very much on this area2, the Hausa being in fact the only ethnic group whose musical culture can be said to have been thoroughly explored3. Kanuri, Manga, and Shoa music are almost unknown, while the musical cultures of the Kanembu and Kotoko received at least some attention in few articles and casual record notes4. As for the Fulani of Cameroon some records exist 5, but no written information on their music is available. Hence, this paper attempts to give a general account of the musical organology of the Fulani in North Cameroon and to contribute to the completion of ethnomusicological knowledge in this area6 through the presentation of new material and the basic facts of Fulani organology (names of instruments and their parts, social usage, history). -

Oral Performance of Ìrègún Music in Yagbaland, Kogi State, Nigeria: an Overview

ORAL PERFORMANCE OF ÌRÈGÚN MUSIC IN YAGBALAND, KOGI STATE, NIGERIA: AN OVERVIEW Stephen Olusegun Titus, Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria. Abstract Performance is one of the major arts in most African countries. Among the Yoruba in Nigeria several genre of oral performance has been researched and documented. These include the ijala, iwi, oriki ekun iyawo, Iyere Ifa, iwure, among others. However, very little attention and studies have been committed to oral performance of Ìrègún chants and songs in Yagbaland. This paper, therefore, focuses on the evaluation of oral performance of Ìrègún chants and songs among Yagba people in Kogi State, located in North central of Nigeria. Primary data were collected through 3 In-depth and 3 Key Informant interviews of leaders and members of Ìrègún musical groups. In addition to 3 Participant Observation and 3 Non-Participant Observation meth- ods from Yagba-West, Yagba-East and Mopamuro Local Government Areas of Kogi State, music recordings, photographs of Ìrègún performances, and 6 chants were purposefully sampled. Secondary data were collected through library, archival and Internet sources. Although closely interwoven, Ìrègún performance is structured into preparation, actual and post-performance activities. While chanting, singing, playing of musical instruments and dancing forms the performance dimensions. Ire- gun music serves as veritable mirror and cultural preserver in Yagba communities. Keywords: Iregun Music; Performance; Yagbaland; Chants and Songs Epiphany: Journal of Transdisciplinary Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, (2015) © Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences 9 S.O. Titus Introduction Performance of oral genre varies in Yoruba culture as varied as contexts for per- formance. In essence, oral performance can only be realized when it is actually performed. -

P a R L I a M E N T a R I a N S F O R G L O B a L a C T I

06 P a r l i a m e n t a r i a n s f o r G l o b a l A c t i o n PARLIAMENTARY SEMINAR ON HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN WEST AFRICA: THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTARIANS In collaboration with: Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Parliament Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Executive Secretariat Office of Human Trafficking & Child Labor, Federal Republic of Nigeria National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) Women’s Trafficking & Child Labour Eradication Foundation (WOTCLEF) International Labour Organization (ILO) International Organization for Migration (IOM) With the support of The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation The Federal Republic of Nigeria The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) European Commission Joshua Hall, Protea Hotel Abuja, Nigeria February 24-25, 2004 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Members of Parliaments Bénin Dep. Nouhoum Assouman First Rapporteur, ECOWAS Committee on Foreign Affairs, Cooperation, Defense and Security Member, ECOWAS Committee on Environment and Natural Resources Burkina Faso Dep. Nongma Ernest Ouedraogo Member, ECOWAS Committee on Laws, Regulations, Legal and Judicial Affairs - Human Rights and Free Movement of Persons Dep. Cecile Beloum Vice-Chair, ECOWAS Committee on Women and Children’s Rights 211 East 43rd Street, Suite 1604, New York, NY 10017, USA T: 1-212-687-7755 F:1-212-687-8409 E-mail: [email protected] PGA Parliamentary Seminar on Human Trafficking in West Africa Page 2 Cape Verde Dep. Atelano Joao de Henrique Dias da Fonseca Member, ECOWAS Committee on Women and Children’s Rights Côte d’Ivoire Dep. -

Philosophical Rumination on Gelede: an Ultra-Spectacle Performance

CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2016 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 2 2016 Vol XIII No 2 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY CULTURE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL ISBN 978-3-631-71562-8 www.peterlang.com CULTURA 2016_271562_VOL_13_No2_GR_A5Br.indd 1 14.11.16 KW 46 10:45 CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2016 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 2 2016 Vol XIII No 2 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY CULTURE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL www.peterlang.com CULTURA 2016_271562_VOL_13_No2_GR_A5Br.indd 1 14.11.16 KW 46 10:45 CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY Cultura. -

ECFG Chad 2021 Ed1r.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Army flag officer tours Chadian hospital with the facility commander). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Chad, focusing on unique C cultural features of Chadian society had and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo: Traditionally, Chadian girls start covering their heads at a young age, courtesy of CultureGrams, ProQuest). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

Module 1 AFRO-LATIN AMERICAN and POPULAR MUSIC

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Regional Office IX, Zamboanga Peninsula 10 Zest for Progress Zeal of Partnership MUSIC Quarter 2, Wk.1 - Module 1 AFRO-LATIN AMERICAN AND POPULAR MUSIC Name of Learner: ___________________________ Grade & Section: ___________________________ 0 Name of School: ___________________________ WHAT I NEED TO KNOW KkKNOW Music has always been an important part in the daily life of the African, whether for work, religion, ceremonies, or even communication. Singing, dancing, hand clapping and the beating of drums are essential to many African ceremonies, including those for birth, death, initiation, marriage, and funerals. Music and dance are also important to religious expression and political events. However, because of its wide influences on global music that has permeated contemporary American, Latin American, and European styles, there has been a growing interest in its own cultural heritage and musical sources. In this module, it contains review on the different elements of music and to analyze the characteristics of Afro-Latin American and popular music were: African music, Latin American music, Jazz music, and Popular music. Also includes the vocal forms, instruments, vocal and dance, and instrumental forms mentioned above. At the end of this module, you are expected to: 1. Analyzes musical characteristics of Afro-Latin American and popular music through listening activities. ( MU10AP-IIa-h-5) WHAT I KNOW Directions: Read and understand the questions carefully and write your answers on the blanks provided. 1. What is the overall quality of sound of a piece, most often indicated by the number/layer of voices in the music ? Answer: ________________ 2. -

Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 9, No. 4, 2013, pp. 23-29 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020130904.2598 www.cscanada.org Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie Adepeju Oti[a],*; Oyebola Ayeni[b] [a]Ph.D, Née Aderogba. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. [b] INTRODUCTION Ph.D. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. *Corresponding author. Culture refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, Received 16 March 2013; accepted 11 July 2013 hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects Abstract and possessions acquired by a group of people in the The history of colonisation dates back to the 19th course of generations through individual and group Century. Africa and indeed Nigeria could not exercise striving (Hofstede, 1997). It is a collective programming her sovereignty during this period. In fact, the experience of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group of colonisation was a bitter sweet experience for the or category of people from another. The position that continent of Africa and indeed Nigeria, this is because the ideas, meanings, beliefs and values people learn as the same colonialist and explorers who exploited the members of society determines human nature. People are African and Nigerian economy; using it to develop theirs, what they learn, therefore, culture ultimately determine the quality in a person or society that arises from a were the same people who brought western education, concern for what is regarded as excellent in arts, letters, modern health care, writing and recently technology. -

Singing Yoruba Christianity: Music, Media, and Morality

Yale Journal of Music & Religion Volume 5 Number 2 Music, Sound, and the Aurality of the Environment in the Anthropocene: Spiritual and Article 10 Religious Perspectives 2019 Singing Yoruba Christianity: Music, Media, and Morality Olabode Festus Omojola Mount Holyoke College Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yjmr Recommended Citation Omojola, Olabode Festus (2019) "Singing Yoruba Christianity: Music, Media, and Morality," Yale Journal of Music & Religion: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17132/2377-231X.1182 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Journal of Music & Religion by an authorized editor of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vicki L. Brennan Singing Yoruba Christianity: Music, Media, and Morality Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018. 210 pp. ISBN 978-0-253-03209-6 The Aladura movement, an Africanist were able to simultaneously affirm Christian group that began in western their Christian convictions and Yoruba- Nigeria in the early twentieth century, grounded practices of spirituality. emerged partly in response to what Set against the general history of the Yoruba Christians perceived as cultural Aladura movement, and building on the domination within the Anglican Church of pioneering work of scholars like John the colonial era. Interracial tensions began Peel and Akinyede Omoyajowo,1 Vicky L. to develop within the church because of Brennan’s well-written and well-researched complaints by Yoruba Christians that they ethnographic study focuses on one of the were denied administrative roles, rarely movement’s prominent branches, the appointed as priests, and disallowed from Cherubim and Seraphim (C&S) or Ayo ni o using Yoruba music in Christian worship church, based in Lagos.