A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

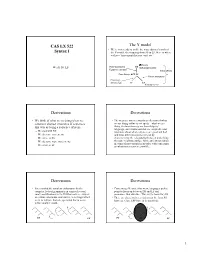

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb. -

Tagalog Pala: an Unsurprising Case of Mirativity

Tagalog pala: an unsurprising case of mirativity Scott AnderBois Brown University Similar to many descriptions of miratives cross-linguistically, Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s clas- sic descriptive grammar of Tagalog describes the second position particle pala as “expressing mild surprise at new information, or an unexpected event or situation.” Drawing on recent work on mi- rativity in other languages, however, we show that this characterization needs to be refined in two ways. First, we show that while pala can be used in cases of surprise, pala itself merely encodes the speaker’s sudden revelation with the counterexpectational nature of surprise arising pragmatically or from other aspects of the sentence such as other particles and focus. Second, we present data from imperatives and interrogatives, arguing that this revelation need not concern ‘information’ per se, but rather the illocutionay update the sentence encodes. Finally, we explore the interactions between pala and other elements which express mirativity in some way and/or interact with the mirativity pala expresses. 1. Introduction Like many languages of the Philippines, Tagalog has a prominent set of discourse particles which express a variety of different evidential, attitudinal, illocutionary, and discourse-related meanings. Morphosyntactically, these particles have long been known to be second-position clitics, with a number of authors having explored fine-grained details of their distribution, rela- tive order, and the interaction of this with different types of sentences (e.g. Schachter & Otanes (1972), Billings & Konopasky(2003) Anderson(2005), Billings(2005) Kaufman(2010)). With a few recent exceptions, however, comparatively little has been said about the semantics/prag- matics of these different elements beyond Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s pioneering work (which is quite detailed given their broad scope of their work). -

Evidentiality

Evidentiality This section covers evidentiality, mirativity, and validational force, as separate concepts that are closely intertwined. Evidentiality in Balti is expressed with clause-final particles, and are generally uninflected for tense or aspect. There is a distinction between the sources of evidence for a statement, and a multi-tiered distinction in validational force. 1 Hearsay In Balti, information that the speaker has experienced first-hand, or has any kind of first- hand knowledge of, is unmarked. In the first example below, the speaker has absolute knowledge that it’s raining, from experiencing it himself; perhaps he is outside and feels the rain hitting his skin, or sees it from a window. (1) namkor oŋ-en jʊt rain come-PROG COP ‘It’s raining.’ (first-hand knowledge) If the speaker gained this knowledge from another person, without witnessing the event himself, he expresses this source of information with the hearsay particle ‘lo’, which always occurs clause-finally. (2) namkor oŋ-en jʊt lo Rain come-PROG COP HSY ‘It’s raining.’ (hearsay) This particle occurs when the speaker is telling someone else, other than the person he received the information from. In other words, if I told Muhammad that it’s raining, and he went to tell someone else that it’s raining, he would express it using example 2 above. In this scenario, Muhammad had been in a basement all day with no windows and thus didn’t perceive any evidence of rain, and I had first-hand knowledge that it’s raining. This particle is uninflected for tense/aspect, and can be used with any tense. -

Like, Hedging and Mirativity. a Unified Account

Like, hedging and mirativity. A unified account. Abstract (4) Never thought I would say this, but Lil’ Wayne, is like. smart. We draw a connection between ‘hedging’ (5) My friend I used to hang out with is like use of the discourse particle like in Amer- . rich now. ican English and its use as a mirative marker of surprise. We propose that both (6) Whoa! I like . totally won again! uses of like widen the size of a pragmati- cally restricted set – a pragmatic halo vs. a In (4), the speaker is signaling that they did not doxastic state. We thus derive hedging and expect to discover that Lil Wayne is smart; in (5) surprise effects in a unified way, outlining the speaker is surprised to learn that their former an underlying link between the semantics friend is now rich; and in (6) the speaker is sur- of like and the one of other mirative mark- prised by the fact that they won again. ers cross-linguistically. After presenting several diagnostics that point to a genuine empirical difference between these 1 Introduction uses, we argue that they do in fact share a core grammatical function: both trigger the expansion Mirative expressions, which mark surprising in- of a pragmatically restricted set: the pragmatic formation (DeLancey 1997), are often expressed halo of an expression for the hedging variant; and through linguistic markers that are also used to en- the doxastic state of the speaker for the mirative code other, seemingly unrelated meanings – e.g., use. We derive hedging and mirativity as effects evidential markers that mark lack of direct evi- of the particular type of object to which like ap- dence (Turkish: Slobin and Aksu 1982; Peterson plies. -

Intensifiers, Reflexivity and Logophoricity in Axaxdərə Akhvakh

Conference on the Languages of the Caucasus Leipzig, 07 – 09 December 2007 Intensifiers, reflexivity and logophoricity in Axaxdərə Akhvakh Denis CREISSELS Université Lumière (Lyon2) e-mail: [email protected] 1. Introduction Akhvakh is a Nakh-Daghestanian language belonging to the Andic branch of the Avar-ADDic-Tsezic family, spoken in the western part of Daghestan and in the village of Axaxdərə near Zaqatala (Azerbaijan). The variety of Akhvakh spoken in Axaxdərə (henceforth AD Akhvakh) is very close to the Northern Akhvakh varieties spoken in the Axvaxskij Rajon of Daghestan (henceforth AR Akhvakh), presented in Magomedbekova 1967 and Magomedova & Abdullaeva 2007. AD Akhvakh shows no particular affinity with any of the Southern Akhvakh dialects spoken in three villages (Cegob, Ratlub and Tljanub) of the Šamil’kij Rajon (formerly Sovetskij Rajon). The analysis of Akhvakh intensifiers, reflexives and logophorics proposed in this paper is entirely based on a corpus of narrative texts I collected in Axaxdərə between June 2005 and June 2007.1 I will be concerned here by the uses of the pronoun ži-CL (CL = class marker) in its simple form and in the form enlarged by the addition of the intensifying particle -da. The use of identical or related forms in intensifying, reflexive, and logophoric functions is attested in many languages of the world, and pronouns cognate with Akhvakh ži-CL fulfilling similar functions are found in the other Andic languages, but in some details of its use, Akhvakh ži-CL shows features which deserve to be examined. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes basic information about Akhvakh morphosyntax. -

Minimal Pronouns1

1 Minimal Pronouns1 Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Bound Variable Pronouns Angelika Kratzer University of Massachusetts at Amherst June 2006 Abstract The paper challenges the widely accepted belief that the relation between a bound variable pronoun and its antecedent is not necessarily submitted to locality constraints. It argues that the locality constraints for bound variable pronouns that are not explicitly marked as such are often hard to detect because of (a) alternative strategies that produce the illusion of true bound variable interpretations and (b) language specific spell-out noise that obscures the presence of agreement chains. To identify and control for those interfering factors, the paper focuses on ‘fake indexicals’, 1st or 2nd person pronouns with bound variable interpretations. Following up on Kratzer (1998), I argue that (non-logophoric) fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features and acquire the remaining features via chains of local agreement relations established in the syntax. If fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features, we need a principled account of what those features are. The paper derives such an account from a semantic theory of pronominal features that is in line with contemporary typological work on possible pronominal paradigms. Keywords: agreement, bound variable pronouns, fake indexicals, meaning of pronominal features, pronominal ambiguity, typologogy of pronouns. 1 . I received much appreciated feedback from audiences in Paris (CSSP, September 2005), at UC Santa Cruz (November 2005), the University of Saarbrücken (workshop on DPs and QPs, December 2005), the University of Tokyo (SALT XIII, March 2006), and the University of Tromsø (workshop on decomposition, May 2006).