Affirmative and Negated Modality*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Root Modality and Thematic Relations in Tagalog and English*

Proceedings of SALT 26: 775–794, 2016 On root modality and thematic relations in Tagalog and English* Maayan Abenina-Adar Nikos Angelopoulos UCLA UCLA Abstract The literature on modality discusses how context and grammar interact to produce different flavors of necessity primarily in connection with functional modals e.g., English auxiliaries. In contrast, the grammatical properties of lexical modals (i.e., thematic verbs) are less understood. In this paper, we use the Tagalog necessity modal kailangan and English need as a case study in the syntax-semantics of lexical modals. Kailangan and need enter two structures, which we call ‘thematic’ and ‘impersonal’. We show that when they establish a thematic dependency with a subject, they express necessity in light of this subject’s priorities, and in the absence of an overt thematic subject, they express necessity in light of priorities endorsed by the speaker. To account for this, we propose a single lexical entry for kailangan / need that uniformly selects for a ‘needer’ argument. In thematic constructions, the needer is the overt subject, and in impersonal constructions, it is an implicit speaker-bound pronoun. Keywords: modality, thematic relations, Tagalog, syntax-semantics interface 1 Introduction In this paper, we observe that English need and its Tagalog counterpart, kailangan, express two different types of necessity depending on the syntactic structure they enter. We show that thematic constructions like (1) express necessities in light of priorities of the thematic subject, i.e., John, whereas impersonal constructions like (2) express necessities in light of priorities of the speaker. (1) John needs there to be food left over. -

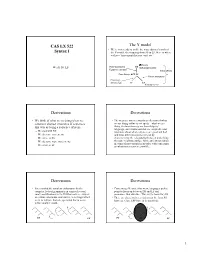

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Prosodic Focus∗

Prosodic Focus∗ Michael Wagner March 10, 2020 Abstract This chapter provides an introduction to the phenomenon of prosodic focus, as well as to the theory of Alternative Semantics. Alternative Semantics provides an insightful account of what prosodic focus means, and gives us a notation that can help with better characterizing focus-related phenomena and the terminology used to describe them. We can also translate theoretical ideas about focus and givenness into this notation to facilitate a comparison between frameworks. The discussion will partly be structured by an evaluation of the theories of Givenness, the theory of Relative Givenness, and Unalternative Semantics, but we will cover a range of other ideas and proposals in the process. The chapter concludes with a discussion of phonological issues, and of association with focus. Keywords: focus, givenness, topic, contrast, prominence, intonation, givenness, context, discourse Cite as: Wagner, Michael (2020). Prosodic Focus. In: Gutzmann, D., Matthewson, L., Meier, C., Rullmann, H., and Zimmermann, T. E., editors. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics. Wiley{Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781118788516.sem133 ∗Thanks to the audiences at the semantics colloquium in 2014 in Frankfurt, as well as the participants in classes taught at the DGFS Summer School in T¨ubingen2016, at McGill in the fall of 2016, at the Creteling Summer School in Rethymnos in the summer of 2018, and at the Summer School on Intonation and Word Order in Graz in the fall of 2018 (lectures published on OSF: Wagner, 2018). Thanks also for in-depth comments on an earlier version of this chapter by Dan Goodhue and Lisa Matthewson, and two reviewers; I am also indebted to several discussions of focus issues with Aron Hirsch, Bernhard Schwarz, and Ede Zimmermann (who frequently wanted coffee) over the years. -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Epistemic Modality, Mind, and Mathematics

Epistemic Modality, Mind, and Mathematics Hasen Khudairi June 20, 2017 c Hasen Khudairi 2017, 2020 All rights reserved. 1 Abstract This book concerns the foundations of epistemic modality. I examine the nature of epistemic modality, when the modal operator is interpreted as con- cerning both apriority and conceivability, as well as states of knowledge and belief. The book demonstrates how epistemic modality relates to the compu- tational theory of mind; metaphysical modality; deontic modality; the types of mathematical modality; to the epistemic status of undecidable proposi- tions and abstraction principles in the philosophy of mathematics; to the apriori-aposteriori distinction; to the modal profile of rational propositional intuition; and to the types of intention, when the latter is interpreted as a modal mental state. Each essay is informed by either epistemic logic, modal and cylindric algebra or coalgebra, intensional semantics or hyperin- tensional semantics. The book’s original contributions include theories of: (i) epistemic modal algebras and coalgebras; (ii) cognitivism about epistemic modality; (iii) two-dimensional truthmaker semantics, and interpretations thereof; (iv) the ground-theoretic ontology of consciousness; (v) fixed-points in vagueness; (vi) the modal foundations of mathematical platonism; (vii) a solution to the Julius Caesar problem based on metaphysical definitions availing of notions of ground and essence; (viii) the application of epistemic two-dimensional semantics to the epistemology of mathematics; and (ix) a modal logic for rational intuition. I develop, further, a novel approach to conditions of self-knowledge in the setting of the modal µ-calculus, as well as novel epistemicist solutions to Curry’s and the liar paradoxes. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 40 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall 2008 2008 Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell Quinnipiac University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Farrell, Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions, 40 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 1 (2008). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell* I. INTRODUCTION Does it matter that the editors of thirty-three law journals, including those at Yale and Michigan, think that there is a "passive tense"? l Does it matter that the United States Courts of Appeals for the Sixth2 and Eleventh3 Circuits think that there is a "passive mood"? Does it matter that the editors of fourteen law reviews think that there is a "subjunctive tense"?4 Does it matter that the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit thinks that there is a "subjunctive voice'"? 5 There is, in fact, no "passive tense" or "passive mood." The passive is a voice. 6 There is no "subjunctive voice" or "subjunctive tense." The subjunctive is a mood.7 The examples in the first paragraph suggest that there is widespread unfamiliarity among lawyers and law students * B.A., Trinity College; J.D., Harvard University; Professor, Quinnipiac University School of Law. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

Epistemic Modality and Evidentiality in Gitksan at the Semantics-Pragmatics Interface By

Epistemic Modality and Evidentiality in Gitksan at the Semantics-Pragmatics Interface by Tyler Roy Gösta Peterson B.Mus., University of British Columbia, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Linguistics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April, 2010 c Tyler Roy Gösta Peterson 2010 Abstract The aim of this dissertation is to provide an empirically driven, theoretically informed investigation of how speakers of Gitksan, a Tsimshianic language spoken in the northwest coast of Canada, express knowledge about the world around them. There are three main goals that motivate this investigation, summarized below: (1) (i.) To provide the first detailed description of the evidential and modal system in Gitksan. (ii.) To provide a formal semantic and pragmatic account of this system that adequately explains the meanings of the modals and evidentials, as well as how they are used in discourse. (iii.) To identify and examine the specific properties the Gitksan evidential/modal system brings to bear on current theories of semantics and pragmatics, as well as the consequences this analysis has on the study of modality and evidentiality cross-linguistically. In addition to documenting the evidential and modal meanings in Gitksan, I test and work through a variety of theoretical tools from the literature designed to investigate evidentiality and modality in a language. This begins by determining what level of mean- ing the individual evidentials in Gitksan operate on. The current state of research into the connection between evidentiality and epistemic modality has identified two different types of evidentials defined by the level of meaning they operate on: propositional and illocutionary evidentials. -

An Ultra-Condensed Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Two-Hour Tutorial at NICTA (National Information and Communication Technologies Australia)

An ultra-condensed introduction to Discourse Analysis: two-hour tutorial at NICTA (National Information and Communication Technologies Australia) Rogelio Nazar Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso [email protected] 23 October 2015 Abstract: Linguistics has historically been devoted to the study of language as a system rather than its manifestation in particular texts. In spite of this, Discourse Analysis (DA) has been established for more than 60 years as a place of convergence of many disciplines interested in discourse. This tutorial is aimed at people with little or no knowledge of linguistic terminology and its purpose is to offer a shallow introduction to DA. This tutorial will not specifically address computational procedures for text analysis. On the contrary, the analytical methods explained here are to be conducted manually, but with systematic and almost mechanical methods. This is mainly a practical tutorial and the focus will be on analysing a real text in English. The first part presents the theoretical principles and analytical tools, while the rest is devoted to practical exercises implementing the proposed method. Given the limitations of time, this tutorial only comments upon a short number concepts. 1. Introduction It is a real pleasure for me to be here today in this not very sunny day in Canberra and I am delighted to have all of you here. As you probably know, I have been entrusted with the impossible task of summarizing 60 years of research in discourse analysis (DA) in a couple of hours. Facing such challenge, what I am going to do is not really to offer a real introduction, because we would need a semester course just to cover the essential readings.