Minimal Pronouns1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Semantics in Generative Grammar. by Irene Heim & Angelika Kratzer

Semantics in generative grammar. By Irene Heim & Angelika Kratzer. Malden & Oxford: Blackwell, 1998. Pp. ix, 324. Introduction to natural language semantics. By Henriëtte de Swart. Stanford: CSLI Publications, 1998. Pp. xiv, 257. Although there aren’t that many text books on formal semantics, their average quality is quite good, and these two recent additions don’t lower the standard by any means. ‘Semantics in generative grammar’ (SGG) is the more innovative of the two. As its title indicates, SGG focuses its attention on the syntax/semantics interface, with particular emphasis on quantification and anaphora. These two subjects are discussed in considerable detail, while many others receive only a cursory treatment or are not addressed at all. We learn from the preface that this was a deliberate choice: ‘We want to help students develop the ability for semantic analysis, and, in view of this goal, we think that exploring a few topics in detail is more effective than offering a bird’s-eye view of everything.’ (p. ix) Having enjoyed the results of Heim and Kratzer’s explorations, I can only agree with this judgment. SGG falls into three main parts. The first part introduces the two notions that are at the heart of the formal semantics enterprise, viz. truth conditions and compositionality, and then goes on to develop a compositional truth- conditional semantics for a core fragment of English. The second part discusses variable binding and quantification, and the third part is an in-depth discussion of anaphora. All these developments are kept within an extensional framework. 06-09-1999 1 Intensional phenomena are addressed only briefly, in the last chapter of the book. -

Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics and Pragmatics Christopher Gauker Semantics deals with the literal meaning of sentences. Pragmatics deals with what speakers mean by their utterances of sentences over and above what those sentences literally mean. However, it is not always clear where to draw the line. Natural languages contain many expressions that may be thought of both as contributing to literal meaning and as devices by which speakers signal what they mean. After characterizing the aims of semantics and pragmatics, this chapter will set out the issues concerning such devices and will propose a way of dividing the labor between semantics and pragmatics. Disagreements about the purview of semantics and pragmatics often concern expressions of which we may say that their interpretation somehow depends on the context in which they are used. Thus: • The interpretation of a sentence containing a demonstrative, as in “This is nice”, depends on a contextually-determined reference of the demonstrative. • The interpretation of a quantified sentence, such as “Everyone is present”, depends on a contextually-determined domain of discourse. • The interpretation of a sentence containing a gradable adjective, as in “Dumbo is small”, depends on a contextually-determined standard (Kennedy 2007). • The interpretation of a sentence containing an incomplete predicate, as in “Tipper is ready”, may depend on a contextually-determined completion. Semantics and Pragmatics 8/4/10 Page 2 • The interpretation of a sentence containing a discourse particle such as “too”, as in “Dennis is having dinner in London tonight too”, may depend on a contextually determined set of background propositions (Gauker 2008a). • The interpretation of a sentence employing metonymy, such as “The ham sandwich wants his check”, depends on a contextually-determined relation of reference-shifting. -

Definiteness Determined by Syntax: a Case Study in Tagalog 1 Introduction

Definiteness determined by syntax: A case study in Tagalog1 James N. Collins Abstract Using Tagalog as a case study, this paper provides an analysis of a cross-linguistically well attested phenomenon, namely, cases in which a bare NP’s syntactic position is linked to its interpretation as definite or indefinite. Previous approaches to this phenomenon, including analyses of Tagalog, appeal to specialized interpretational rules, such as Diesing’s Mapping Hypothesis. I argue that the patterns fall out of general compositional principles so long as type-shifting operators are available to the gram- matical system. I begin by weighing in a long-standing issue for the semantic analysis of Tagalog: the interpretational distinction between genitive and nominative transitive patients. I show that bare NP patients are interpreted as definites if marked with nominative case and as narrow scope indefinites if marked with genitive case. Bare NPs are understood as basically predicative; their quantificational force is determined by their syntactic position. If they are syntactically local to the selecting verb, they are existentially quantified by the verb itself. If they occupy a derived position, such as the subject position, they must type-shift in order to avoid a type-mismatch, generating a definite interpretation. Thus the paper develops a theory of how the position of an NP is linked to its interpretation, as well as providing a compositional treatment of NP-interpretation in a language which lacks definite articles but demonstrates other morphosyntactic strategies for signaling (in)definiteness. 1 Introduction Not every language signals definiteness via articles. Several languages (such as Russian, Kazakh, Korean etc.) lack articles altogether. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Nouns, Adjectives, Verbs, and Adverbs

Unit 1: The Parts of Speech Noun—a person, place, thing, or idea Name: Person: boy Kate mom Place: house Minnesota ocean Adverbs—describe verbs, adjectives, and other Thing: car desk phone adverbs Idea: freedom prejudice sadness --------------------------------------------------------------- Answers the questions how, when, where, and to Pronoun—a word that takes the place of a noun. what extent Instead of… Kate – she car – it Many words ending in “ly” are adverbs: quickly, smoothly, truly A few other pronouns: he, they, I, you, we, them, who, everyone, anybody, that, many, both, few A few other adverbs: yesterday, ever, rather, quite, earlier --------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------- Adjective—describes a noun or pronoun Prepositions—show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and another word in the sentence. Answers the questions what kind, which one, how They begin a prepositional phrase, which has a many, and how much noun or pronoun after it, called the object. Articles are a sub category of adjectives and include Think of the box (things you have do to a box). the following three words: a, an, the Some prepositions: over, under, on, from, of, at, old car (what kind) that car (which one) two cars (how many) through, in, next to, against, like --------------------------------------------------------------- Conjunctions—connecting words. --------------------------------------------------------------- Connect ideas and/or sentence parts. Verb—action, condition, or state of being FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) Action (things you can do)—think, run, jump, climb, eat, grow A few other conjunctions are found at the beginning of a sentence: however, while, since, because Linking (or helping)—am, is, are, was, were --------------------------------------------------------------- Interjections—show emotion. -

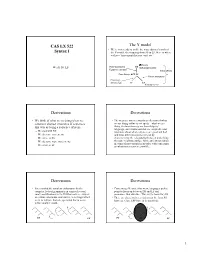

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals As Windows Into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer

University of Massachusetts Amherst From the SelectedWorks of Angelika Kratzer 2009 Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer Available at: https://works.bepress.com/angelika_kratzer/ 6/ Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer This article argues that natural languages have two binding strategies that create two types of bound variable pronouns. Pronouns of the first type, which include local fake indexicals, reflexives, relative pronouns, and PRO, may be born with a ‘‘defective’’ feature set. They can ac- quire the features they are missing (if any) from verbal functional heads carrying standard -operators that bind them. Pronouns of the second type, which include long-distance fake indexicals, are born fully specified and receive their interpretations via context-shifting -operators (Cable 2005). Both binding strategies are freely available and not subject to syntactic constraints. Local anaphora emerges under the assumption that feature transmission and morphophonological spell-out are limited to small windows of operation, possibly the phases of Chomsky 2001. If pronouns can be born underspecified, we need an account of what the possible initial features of a pronoun can be and how it acquires the features it may be missing. The article develops such an account by deriving a space of possible paradigms for referen- tial and bound variable pronouns from the semantics of pronominal features. The result is a theory of pronouns that predicts the typology and individual characteristics of both referential and bound variable pronouns. Keywords: agreement, fake indexicals, local anaphora, long-distance anaphora, meaning of pronominal features, typology of pronouns 1 Fake Indexicals and Minimal Pronouns Referential and bound variable pronouns tend to look the same. -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Scope Or Pseudoscope? Are There Wide-Scope Indefinites?1

1 Scope or Pseudoscope? Are there Wide-Scope Indefinites?1 Angelika Kratzer, University of Massachusetts at Amherst March 1997 1. The starting point: Fodor and Sag My story begins with a famous example by Janet Fodor and Ivan Sag 2: The Fodor and Sag example (1) Each teacher overheard the rumor that a student of mine had been called before the dean. (1) has a reading where the indefinite NP a student of mine has scope within the that - clause. What the teachers overheard might have been: “A student of Angelika’s was called before the dean”. This reading is expected if indefinite NPs are quantifiers, and quantifier scope is confined to some local domain. (1) has another reading where a student of mine seems to have widest scope, scope even wider than each teacher. There might have been a student of mine, say Sanders, and each teacher overheard the rumor that Sanders was called before the dean. Fodor and Sag argue that this is not an instance of scope. If indefinite NPs seem to have anomalous scope properties, they are not true quantifiers. The apparent wide-scope reading of a student of mine in (1) is really a referential reading. Indefinite NPs, then, are ambiguous between quantificational and referential readings. If they are quantificational, their scope cannot exceed some local domain. If they are referential, they do not have scope at all. They may be easily confused with widest scope existentials, however. Sentence (1) is important for Fodor and Sag’s argument since it offers a third scope possibility for the indefinite NP that doesn’t seem to be there. -

Situation Theory: a Survey

ABSTRACT SITUATION THEORY: A SURVEY Situation semantics was developed as an alternative to possible-worlds semantics. While possible-worlds semantics defines the informational content of sentences in terms of complete descriptions of the way the world is or might be, situation semantics defines the informational content of sentences in terms of partial worlds called situations. Situation theory is a novel informational ontology developed to give situation semantics a rigorous mathematical foundation. In reviewing the literature, we observed that although there are a few texts introducing situation theory in varying levels of detail and systematicity, there has not yet been published, until now, a general survey of the situation-theory literature that might introduce and guide future scholars. We note that a similar, if perhaps less-pressing need exists for a survey of the situation-semantics literature, but regret that we must leave such a survey for others. Jacob Ian Lee December 2011 SITUATION THEORY: A SURVEY by Jacob Ian lee A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science in the College of Science and Mathematics California State University, Fresno December 2011 © 2011 Jacob Ian Lee APPROVED For the Department of Computer Science: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Jacob Ian Lee Thesis Author Todd Wilson (Chair) Computer Science Shigeko Seki Computer Science Shih-Hsi Liu Computer Science For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. -

Pronouns: a Resource Supporting Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (Gnc) Educators and Students

PRONOUNS: A RESOURCE SUPPORTING TRANSGENDER AND GENDER NONCONFORMING (GNC) EDUCATORS AND STUDENTS Why focus on pronouns? You may have noticed that people are sharing their pronouns in introductions, on nametags, and when GSA meetings begin. This is happening to make spaces more inclusive of transgender, gender nonconforming, and gender non-binary people. Including pronouns is a first step toward respecting people’s gender identity, working against cisnormativity, and creating a more welcoming space for people of all genders. How is this more inclusive? People’s pronouns relate to their gender identity. For example, someone who identifies as a woman may use the pronouns “she/her.” We do not want to assume people’s gender identity based on gender expression (typically shown through clothing, hairstyle, mannerisms, etc.) By providing an opportunity for people to share their pronouns, you're showing that you're not assuming what their gender identity is based on their appearance. If this is the first time you're thinking about your pronoun, you may want to reflect on the privilege of having a gender identity that is the same as the sex assigned to you at birth. Where do I start? Include pronouns on nametags and during introductions. Be cognizant of your audience, and be prepared to use this resource and other resources (listed below) to answer questions about why you are making pronouns visible. If your group of students or educators has never thought about gender-neutral language or pronouns, you can use this resource as an entry point. What if I don’t want to share my pronouns? That’s ok! Providing space and opportunity for people to share their pronouns does not mean that everyone feels comfortable or needs to share their pronouns.