3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

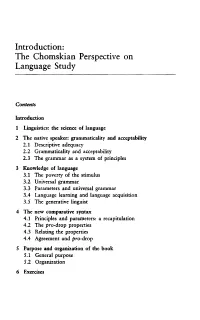

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

Third Declension, That Is, Consonant-Stem Nouns; Patterns I

Chapter 7: Third-Declension Nouns Chapter 7 covers the following: third declension, that is, consonant-stem nouns; patterns in the formation of the nominative singular of third declension; and the agreement between third- declension nouns and first/second-declension adjectives. At the end of the lesson, we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There is only one important rule to remember here: the genitive singular ending in third declension is -is . We’ve already encountered first- and second-declension nouns. Now we’ll address the third. A fair question to ask, and one which some of you may be asking, is why is there a third declension at all? Third declension is Latin’s “catch-all” category for nouns. Into it have been put all nouns whose bases end with consonants ─ any consonant! That makes third declension very different from first and second declension. First declension, as you’ll remember, is dominated by a-stem nouns like femina and cura . Second declension is dominated by o- or u-stem nouns like amicus or oculus . Those vowels give those declensions a certain consistency, but the same is not true of third declension where one form, the nominative singular, is affected by the fact that its ending -s runs into the wide variety of consonants found at the ends of the bases of third-declension nouns, and the collision of those consonants causes irregular forms to appear in the nominative singular. That’s the bad news. The good news is that only one case and number is affected by this, the nominative singular. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

Oksana's BU Paper

ACQUISITION of GENDER in RUSSIAN * Oksana Tarasenkova University of Connecticut 1 The Background In adult Russian grammar the gender feature of nouns is closely related to their declension class. Their relationship was a controversial question that evoked two opposing views regarding the way gender is represented in adult Russian grammar. The representatives of one view argue for gender to be derived from the noun declension class (Declension-to Gender account, Corbett 1982), while proponents of the opposite account argue for the reversed pattern, where the inflectional morphology can be predicted from the information on the noun gender along with a phonological cue (Gender-to-Declension account, Vinogradov 1960, Thelin 1975, Crockett 1976 among others). My goal is to focus on children’s acquisition of gender in Russian in order to compare these two major divisions of research. They provide different morphological analyses of gender forms in Russian; therefore this debate makes different predictions about the acquisition of gender by children. I tested these opposing predictions using children’s data gathered from an experiment to identify what exactly children rely on when assigning gender to nouns. The experiment results support the Declension-to-Gender view and provide evidence that children are significantly more successful at assigning gender to the novel nouns relying on the nominal declension paradigm rather than on the adjectival agreement. The way gender is represented in adults’ competence grammar might not necessarily be the correct model of children’s acquisition of gender. The child has to learn the gender of a significant number of nouns and extract the declensional paradigms first in order to then be able to learn and apply these redundancy rules for novel nouns. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Subject-Verb Agreement

Subject-verb Agreement The subject and the verb of a sentence have a special relationship. Unfortunately, as in most relationships, the subject and verb may disagree at times and then the entire sentence can sound awkward. Identifying this error can be tricky, but there are a few methods that can help you fix that disagreement. Subjects are in italics and verbs are in bold. 1) Make the verb agree with its subject, not with a word that comes between. Note that phrases beginning with prepositions like ‘as well as,’ ‘in addition to,’ ‘accompanied by,’ ‘together with,’ and ‘along with’ do not make a singular subject plural: Incorrect: High levels of air pollution causes damage to the respiratory tract. Correct: High levels of air pollution cause damage to the respiratory tract. Incorrect: The governor, as well as his press secretary, were shot. Correct: The governor, as well as his press secretary, was shot. 2) Treat most subjects joined with ‘and’ as plural unless the parts of the subject form a single unit: Incorrect: Jill’s natural ability and her desire to help others has led to a career in the ministry. Correct: Jill’s natural ability and her desire to help others have led to a career in the ministry. Incorrect: Strawberries and cream were a last-minute addition to the menu. Correct: Strawberries and cream was a last-minute addition to the menu. 3) With subjects connected by ‘or’ or ‘nor’ make the verb agree with the part of the subject nearer to the verb: Incorrect: If a relative or neighbor are abusing a child, notify the police. -

The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

The syntax of answers to negative yes/no-questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University 1. Introduction This paper will argue that answers to polar questions or yes/no-questions (YNQs) in English are elliptical expressions with basically the structure (1), where IP is identical to the LF of the IP of the question, containing a polarity variable with two possible values, affirmative or negative, which is assigned a value by the focused polarity expression. (1) yes/no Foc [IP ...x... ] The crucial data come from answers to negative questions. English turns out to have a fairly complicated system, with variation depending on which negation is used. The meaning of the answer yes in (2) is straightforward, affirming that John is coming. (2) Q(uestion): Isn’t John coming, too? A(nswer): Yes. (‘John is coming.’) In (3) (for speakers who accept this question as well formed), 1 the meaning of yes alone is indeterminate, and it is therefore not a felicitous answer in this context. The longer version is fine, affirming that John is coming. (3) Q: Isn’t John coming, either? A: a. #Yes. b. Yes, he is. In (4), there is variation regarding the interpretation of yes. Depending on the context it can be a confirmation of the negation in the question, meaning ‘John is not coming’. In other contexts it will be an infelicitous answer, as in (3). (4) Q: Is John not coming? A: a. Yes. (‘John is not coming.’) b. #Yes. In all three cases the (bare) answer no is unambiguous, meaning that John is not coming. -

1 Noun Classes and Classifiers, Semantics of Alexandra Y

1 Noun classes and classifiers, semantics of Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, Melbourne Abstract Almost all languages have some grammatical means for the linguistic categorization of noun referents. Noun categorization devices range from the lexical numeral classifiers of South-East Asia to the highly grammaticalized noun classes and genders in African and Indo-European languages. Further noun categorization devices include noun classifiers, classifiers in possessive constructions, verbal classifiers, and two rare types: locative and deictic classifiers. Classifiers and noun classes provide a unique insight into how the world is categorized through language in terms of universal semantic parameters involving humanness, animacy, sex, shape, form, consistency, orientation in space, and the functional properties of referents. ABBREVIATIONS: ABS - absolutive; CL - classifier; ERG - ergative; FEM - feminine; LOC – locative; MASC - masculine; SG – singular 2 KEY WORDS: noun classes, genders, classifiers, possessive constructions, shape, form, function, social status, metaphorical extension 3 Almost all languages have some grammatical means for the linguistic categorization of nouns and nominals. The continuum of noun categorization devices covers a range of devices from the lexical numeral classifiers of South-East Asia to the highly grammaticalized gender agreement classes of Indo-European languages. They have a similar semantic basis, and one can develop from the other. They provide a unique insight into how people categorize the world through their language in terms of universal semantic parameters involving humanness, animacy, sex, shape, form, consistency, and functional properties. Noun categorization devices are morphemes which occur in surface structures under specifiable conditions, and denote some salient perceived or imputed characteristics of the entity to which an associated noun refers (Allan 1977: 285). -

Number Systems in Grammar Position Paper

1 Language and Culture Research Centre: 2018 Workshop Number systems in grammar - position paper Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald I Introduction I 2 The meanings of nominal number 2 3 Special number distinctions in personal pronouns 8 4 Number on verbs 9 5 The realisation of number 12 5.1 The forms 12 5.2 The loci: where number is shown 12 5.3 Optional and obligatory number marking 14 5.4 The limits of number 15 5.4.1 Number and the meanings of nouns 15 5.4.2 'Minor' numbers 16 5.4.3 The limits of number: nouns with defective number values 16 6 Number and noun categorisation 17 7 Markedness 18 8 Split, or mixed, number systems 19 9 Number and social deixis 19 10 Expressing number through other means 20 11 Number systems in language history 20 12 Summary 21 Further readings 22 Abbreviations 23 References 23 1 Introduction Every language has some means of distinguishing reference to one individual from reference to more than one. Number reference can be coded through lexical modifiers (including quantifiers of various sorts or number words etc.), or through a grammatical system. Number is a referential property of an argument of the predicate. A grammatical system of number can be shown either • Overtly, on a noun, a pronoun, a verb, etc., directly referring to how many people or things are involved; or • Covertly, through agreement or other means. Number may be marked: • within an NP • on the head of an NP • by agreement process on a modifier (adjective, article, demonstrative, etc.) • through agreement on verbs, or special suppletive or semi-suppletive verb forms which may code the number of one or more verbal arguments, or additional marker on the verb. -

Person and Number Agreement in American Sign Language

Person and Number Agreement in American Sign Language Hyun-Jong Hahm The University of Texas at Austin Proceedings of the HPSG06 Conference Linguistic Modelling Laboratory Institute for Parallel Processing Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Sofia Held in Varna Stefan Müller (Editor) 2006 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract American Sign Language (ASL) has a group of verbs showing agreement with the subject or/and object argument. There has not been analysis on especially number agreement. This paper analyzes person and number agreement within the HPSG framework. I discuss person and number hierarchy in ASL. The argument of agreement verbs can be omitted as in languages like Italian. The constraints on the type agreement-verb have the information on argument optionality. 1 Introduction1 During the past fifty years sign languages have been recognized as genuine languages with their own distinctive structure. Signed languages and spoken languages have many similarities, but also differ due to the different modalities: visual-gestural modality vs. auditory-vocal modality. This paper examines a common natural language phenomenon, verb agreement in American Sign Language (ASL, hereafter) through the recordings of a native signer within the framework of Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG).2 Most analyses of signed languages have been based largely on transformational grammar. Cormier et al. (1999) discusses locus agreement in ASL, which is the first work in the HPSG framework. However, their work is limited to locus agreement with singular arguments. This paper examines person and number verb agreement. One type of verb shows agreement with object or/and subject arguments. Main focus in this paper is to show what constraints agreement verbs have, to explain the subject/object-verb agreement. -

Syntax-Semantics Interface

: Syntax-Semantics Interface http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/mitecs/chierchia.html Subscriber : California Digital Library » LOG IN Home Library What's New Departments For Librarians space GO REGISTER Advanced Search The CogNet Library : References Collection : Table of Contents : Syntax-Semantics Interface «« Previous Next »» A commonplace observation about language is that it consists of the systematic association of sound patterns with meaning. SYNTAX studies the structure of well-formed phrases (spelled out as sound sequences); SEMANTICS deals with the way syntactic structures are interpreted. However, how to exactly slice the pie between these two disciplines and how to map one into the other is the subject of controversy. In fact, understanding how syntax and semantics interact (i.e., their interface) constitutes one of the most interesting and central questions in linguistics. Traditionally, phenomena like word order, case marking, agreement, and the like are viewed as part of syntax, whereas things like the meaningfulness of a well-formed string are seen as part of semantics. Thus, for example, "I loves Lee" is ungrammatical because of lack of agreement between the subject and the verb, a phenomenon that pertains to syntax, whereas Chomky's famous "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" is held to be syntactically well-formed but semantically deviant. In fact, there are two aspects of the picture just sketched that one ought to keep apart. The first pertains to data, the second to theoretical explanation. We may be able on pretheoretical grounds to classify some linguistic data (i.e., some native speakers' intuitions) as "syntactic" and others as "semantic." But we cannot determine a priori whether a certain phenomenon is best explained in syntactic or semantics terms. -

Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto De Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic

Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic To cite this version: Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic. Introduction: Complex Adpo- sitions and Complex Nominal Relators. Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Dejan Stosic, Elena Smirnova. Complex Adpositions in European Languages : A Micro-Typological Approach to Com- plex Nominal Relators, 65, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-30, 2020, Empirical Approaches to Language Typology, 978-3-11-068664-7. 10.1515/9783110686647-001. halshs-03087872 HAL Id: halshs-03087872 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03087872 Submitted on 24 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova & Dejan Stosic Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard CNRS, ENS & Paris Sorbonne Nouvelle; PSL Lattice laboratory, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 1 rue Maurice Arnoux, 92120 Montrouge, France [email protected]