Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto De Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

The Subject of the Estonian Des-Converb1

Helen Plado The Subject of the Estonian des-converb1 Abstract The Estonian des-construction is used as both an implicit-subject and an explicit-subject converb. This article concentrates on the subjects of both and also compares them. In the case of implicit-subject converbs, it is argued that not only the (semantic) subject of the superordinate clause can control the implicit subject of the des-converb, but also the most salient participant (which can sometimes even be the undergoer) of the superordinate clause. The article also discusses under which conditions the undergoer of the superordinate clause can control the implicit subject of the converb. In the case of explicit-subject converbs it is demonstrated which subjects tend to be explicitly present in the des-converb and which are the main properties of the structure and usage of explicit-subject des-converbs. 1. Background A converb is described as a “verb form which depends syntactically on another verb form, but is not its syntactic actant” (Nedjalkov 1995: 97) and as “a nonfinite verb form whose main function is to mark adverbial subordination” (Haspelmath 1995: 3). The Estonian des-form is a non- finite verb form that cannot be the main verb of a sentence. It acts as an adjunct and delivers some adverbial meaning. Hence, the Estonian des- form is a typical converb. One of the main questions in the discussion about converbs is the subject of the converb, consisting of two issues: whether the subject is explicitly present in the converb and if not, then what controls the (implicit) 1 I thank Marja-Liisa Helasvuo, Liina Lindström, and two anonymous reviewers for their highly valuable comments and suggestions. -

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

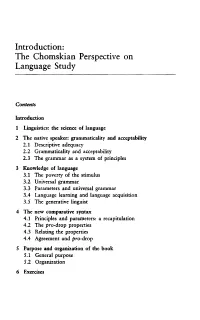

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

0Gpresentparticiples.Pdf

http://www.ToLearnEnglish.com − Resources to learn/teach English (courses, games, grammar, daily page...) Present Participles > Formation The present participle is formed by adding the ending "−−ing" to the infinitive (dropping any silent "e" at the end of the infinitive): to sing −−> singing to take −−> taking to bake −−> baking to be −−> being to have −−> having > Use A. The present participle may often function as an adjective: That's an interesting book. That tree is a weeping willow. B. The present participle can be used as a noun denoting an activity (this form is also called a gerund): Swimming is good exercise. Traveling is fun. C. The present participle can indicate an action that is taking place, although it cannot stand by itself as a verb. In these cases it generally modifies a noun (or pronoun), an adverb, or a past participle: Thinking myself lost, I gave up all hope. Washing clothes is not my idea of a job. Looking ahead is important. D. The present participle may be used with "while" or "by" to express an idea of simultaneity ("while") or causality ("by") : He finished dinner while watching television. By using a dictionary he could find all the words. While speaking on the phone, she doodled. By calling the police you saved my life! E. The present participle of the auxiliary "have" may be used with the past participle to describe a past condition resulting in another action: Having spent all his money, he returned home. Having told herself that she would be too late, she accelerated. TEST A) Find the gerund: 1. -

The Whether Report

Hugvísindasvið The Whether Report: Reclassifying Whether as a Determiner B.A. Essay Gregg Thomas Batson May, 2012 University of Iceland School of Humanities Department of English The Whether Report: Reclassifying Whether as a Determiner B.A. Essay Gregg Thomas Batson Kt.: 0805682239 Supervisor: Matthew Whelpton May, 2012 Abstract This paper examines the use of whether in complement clauses for the purpose of determining the exact syntactic and semantic status of whether in these clauses. Beginning with a background to the complementizer phrase, this paper will note the historical use of whether, and then examine and challenge the contemporary assertion of Radford (2004) and Newson et al. (2006) that whether is a wh-phrase. Furthermore, this paper will investigate the preclusion of whether by Radford and Newson et al. from the complementizer class. Following an alternative course that begins by taking into account the morphology of whether, the paper will then examine two research papers relevant to whether complement clauses. The first is Adger and Quer‘s (2001) paper proposing that certain embedded question clauses have an extra element in their structure that behaves as a determiner and the second paper is from Larson (1985) proposing that or scope is assigned syntactically by scope indicators. Combining the two proposals, this paper comes to a different conclusion concerning whether and introduces a new proposal concerning the syntactic structure and semantic interpretation of interrogative complement clauses. Table of Contents 1. -

The Use of Demonstrative Pronoun and Demonstrative Determiner This in Upper-Level Student Writing: a Case Study

English Language Teaching; Vol. 8, No. 5; 2015 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Use of Demonstrative Pronoun and Demonstrative Determiner this in Upper-Level Student Writing: A Case Study Katharina Rustipa1 1 Faculty of Language and Cultural Studies, Stikubank University (UNISBANK) Semarang, Indonesia Correspondence: Katharina Rustipa, UNISBANK Semarang, Jl. Tri Lomba Juang No.1 Semarang 50241, Indonesia. Tel: 622-4831-1668. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 20, 2015 Accepted: February 26, 2015 Online Published: April 23, 2015 doi:10.5539/elt.v8n5p158 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n5p158 Abstract Demonstrative this is worthy to investigate because of the role of this as a common cohesive device in academic writing. This study attempted to find out the variables underlying the realization of demonstrative this in graduate-student writing of Semarang State University, Indonesia. The data of the study were collected by asking three groups of students (first semester, second semester, third semester students) to write an essay. The collected data were analyzed by identifying, classifying, calculating, and interpreting. Interviewing to several students was also done to find out the reasons underlying the use of attended and unattended this. Comparing the research results to those of the Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Paper (MICUSP) as proficient graduate-student writing was done in order to know the position of graduate-student writing of Semarang State University in reference to MICUSP. The conclusion of the research results is that most occurrences of demonstrative this are attended and these occurrences are stable across levels, similar to those in MICUSP. -

The Grammaticalization of Demonstratives: a Comparative Analysis

Nicholas Catasso 7 Journal of Universal Language 12-1 March 2011, 7-46 The Grammaticalization of Demonstratives: A Comparative Analysis Nicholas Catasso Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia * Abstract An article, irrespective of its distribution across natural languages, dialects and varieties, is a member of the class of determiners which particularizes a noun according to language-specific principles of grammatical and semantic structuring. Definite articles in Indo- European languages – in those grammatical systems where they are present – are derived from ancient demonstratives through a grammaticalization process: given that demonstratives are deictic expressions (i.e. they depend on a frame of reference which is external to that of the speaker and of the interlocutor) with the role of selecting a referent or a set of referents, it is easy to understand what the role of “universal quantifier” of the, which is in English the prototypical – but questionable – example of definiteness, is due to. Demonstratives are frequently reanalyzed across languages as grammatical markers (very often as definite articles, but also as copulas, relative and third person pronouns, sentence connectives, Nicholas Catasso Dipartimento di Scienze del Linguaggio - Dorsoduro 3462 - VENEZIA 30123 (VE) Phone 0039-3463157243; Email: [email protected] Received Oct. 2010; Reviewed Dec. 2010; Revised version received Jan. 2011. 8 The Grammaticalization of Demonstratives: A Comparative Analysis focus markers, etc.). In this article I concentrate on the grammaticalization of the definite article in English, adopting a comparative-contrastive approach (including a wide range of Indo- European languages), given the complexity of the article. Keywords: grammaticalization, definite articles, English, Indo- European languages, definiteness 1. -

Determiners in Various Resources: Grammar Books, Coursebooks And

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature Determiners in various resources: Grammar books, coursebooks and online sources compared Bachelor thesis Brno 2016 Supervisor: Author: doc. PhDr. Renata Povolná, Ph.D. Pavla Fryštáková Declaration: „Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných literárních pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 SB., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o měně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů.“ V Brně dne 16. 3. 2016 ………………………………. Pavla Fryštáková Acknowledgement: I would like to thank doc. PhDr. Renata Povolná, Ph.D., for help and advice provided during the supervision of my bachelor thesis. Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 2 Reference to determiners in grammar books ....................................................... 7 2.1 Grammar books referring to determiners as one topic ....................................... 7 2.1.1 Swan (1996) ................................................................................................ 7 2.1.2 Leech and Svartvik (1975) .......................................................................... 9 2.1.3 Greenbaum and Quirk (1990) ................................................................... 16 2.1.4 -

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: the Principles of Language Structure

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: The Principles of Language Structure Ben Newman March 1, 2018 1 What are we studying in this course? This course is about syntax, which is the subfield of linguistics that deals with how words and phrases can be combined to form correct larger forms (usually referred to as sentences). We’re not particularly interested in the structure of words (morphemes), sounds (phonetics), or writing systems, but instead on the rules underlying how words and phrases can be combined across different languages. These rules are what make up the formal grammar of a language. Formal grammar is similar to what you learn in middle and high school English classes, but is a lot more, well, formal. Instead of classifying words based on meaning or what they “do" in a sentence, formal grammars depend a lot more on where words are in the sentence. For example, in English class you might say an adjective is “a word that modifies a noun”, such as red in the phrase the red ball. A more formal definition of an adjective might be “a word that precedes a noun" or “the first word in an adjective phrase" where the adjective phrase is red ball. Describing a formal grammar involves writing down a lot of rules for a language. 2 I-Language and E-Language Before we get into the nitty-gritty grammar stuff, I want to take a look at two ways language has traditionally been described by linguists. One of these descriptions centers around the rules that a person has in his/her mind for constructing sentences. -

Verbals: Participle Or Gerund? | Verbals Worksheets

Name: ___________________________Key VErbals: Participle or Gerund? A participle is a verb form that functions as an adjective in a sentence. A gerund is a verb form that functions as a noun in a sentence. Below are sentences using either a participle or a gerund. Read each sentence carefully. Write which verbal form appears in the sentence in the blank. 1. The jumping frog landed in her lap. _______________________________________________________________________________ 2. Lucinda had a calling to help other people. _______________________________________________________________________________ 3. The mother barely caught the crawling baby before he went into the street. _______________________________________________________________________________ 4. The house was filled with a haunting spector. _______________________________________________________________________________ 5. Running in the halls is strictly forbidden. _______________________________________________________________________________ 6. They won the award for caring for sick animals. _______________________________________________________________________________ 7. Paul bought new climbing gear. _______________________________________________________________________________ 8. Escaping was the only thought he had. _______________________________________________________________________________ Copyright © 2014 K12reader.com. All Rights Reserved. Free for educational use at home or in classrooms. www.k12reader.com Name: ___________________________Key VErbals: Participle