The Two Be's of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

A Syntactic Analysis of Copular Sentences*

A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF COPULAR SENTENCES* Masato Niimura Nanzan University 1. Introduction Copular is a verb whose main function is to link subjects with predicate complements. In a limited sense, the copular refers to a verb that does not have any semantic content, but links subjects and predicate complements. In a broad sense, the copular contains a verb that has its own meaning and bears the syntactic function of “the copular.” Higgins (1979) analyses English copular sentences and classifies them into three types. (1) a. predicational sentence b. specificational sentence c. identificational sentence Examples are as follows: (2) a. John is a philosopher. b. The bank robber is John Smith. c. That man is Mary’s brother. (2a) is an example of predicational sentence. This type takes a reference as subject, and states its property in predicate. In (2a), the reference is John, and its property is a philosopher. (2b) is an example of specificational sentence, which expresses what meets a kind of condition. In (2b), what meets the condition of the bank robber is John Smith. (2c) is an example of identificational sentence, which identifies two references. This sentence identifies that man and Mary’s brother. * This paper is part of my MA thesis submitted to Nanzan University in March, 2007. This paper was also presented at the Connecticut-Nanzan-Siena Workshop on Linguistic Theory and Language Acquisition, held at Nanzan University on February 21, 2007. I would like to thank the participants for the discussions and comments on this paper. My thanks go to Keiko Murasugi, Mamoru Saito, Tomohiro Fujii, Masatake Arimoto, Jonah Lin, Yasuaki Abe, William McClure, Keiko Yano and Nobuko Mizushima for the invaluable comments and discussions on the research presented in this paper. -

Copula-Less Nominal Sentences and Matrix-C Clauses: a Planar View Of

Copula-less Nominal Sentences and Matrix-C0 Clauses: A Planar View of Clause Structure * Tanmoy Bhattacharya Abstract This paper is an attempt to unify the apparently unrelated sentence types in Bangla, namely, copula-less nominal sentences and matrix-C clauses. In particular, the paper claims that a “Planar” view of clause structure affords us, besides the above unification, a better account of the Kaynean Algorithm (KA, as in Kayne (1998a, b; 1999)) in terms of an interface driven motivation to break symmetry. In order to understand this unification, the invocation of the KA, that proclaims most significantly the ‘non-constituency’ of the C and its complement, is relevant if we agree with the basic assumption of this paper that views both Cs and Classifiers as disjoint from the main body (plane) of the clause. Such a disjunction is exploited further to introduce a new perspective of the structure of clauses, namely, the ‘planar’ view. The unmistakable non-linearity of the KA is seen here as a multi-planar structure creation; the introduction of the C/ CLA thus implies a new plane introduction. KA very strongly implies a planar view of clause structure. The identification of a plane is considered to be as either required by the C-I or the SM interface and it is shown that this view matches up with the duality of semantics, as in Chomsky (2005). In particular, EM (External Merge) is required to introduce or identify a new plane, whereas IM (Internal Merge) is inter- planar. Thus it is shown that inter-planar movements are discourse related, whereas intra-planar movements are not discourse related. -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

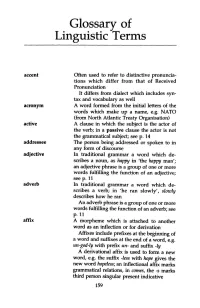

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

A Parallel Analysis of Have-Type Copular Constructions in Two Have-Less Indo-European Languages

A PARALLEL ANALYSIS OF HAVE-TYPE COPULAR CONSTRUCTIONS IN TWO HAVE-LESS INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES Sebastian Sulger Universitat¨ Konstanz Proceedings of the LFG11 Conference Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2011 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract This paper presents data from two Indo-European languages, Irish and Hindi/ Urdu, which do not use verbs for expressing possession (i.e., they do not have a verb comparable to the English verb have). Both of the languages use cop- ula constructions. Hindi/Urdu combines the copula with either a genitive case marker or a postposition on the possessor noun phrase to construct pos- session. Irish achieves the same effect by combining one of two copula ele- ments with a prepositional phrase. I argue that both languages differentiate between temporary and permanent instances, or stage-level and individual- level predication, of possession. The syntactic means for doing so do not overlap between the two: while Hindi/Urdu employs two distinct markers to differentiate between stage-level and individual-level predication, Irish uses two different copulas. A single parallel LFG analysis for both languages is presented based on the PREDLINK analysis. It is shown how the analysis is capable of serving as input to the semantics, which is modeled using Glue Semantics and which differentiates between stage-level and individual-level predication by means of a situation argument. In particular, it is shown that the inalienable/alienable distinction previ- ously applied to the Hindi/Urdu data is insufficient. The reanalysis presented here in terms of the stage-level vs. individual-level distinction can account for the data from Hindi/Urdu in a more complete way. -

Hungarian Copula Constructions in Dependency Syntax and Parsing

Hungarian copula constructions in dependency syntax and parsing Katalin Ilona Simko´ Veronika Vincze University of Szeged University of Szeged Institute of Informatics Institute of Informatics Department of General Linguistics MTA-SZTE Hungary Research Group on Artificial Intelligence [email protected] Hungary [email protected] Abstract constructions? And if so, how can we deal with cases where the copula is not present in the sur- Copula constructions are problematic in face structure? the syntax of most languages. The paper In this paper, three different answers to these describes three different dependency syn- questions are discussed: the function head analy- tactic methods for handling copula con- sis, where function words, such as the copula, re- structions: function head, content head main the heads of the structures; the content head and complex label analysis. Furthermore, analysis, where the content words, in this case, the we also propose a POS-based approach to nominal part of the predicate, are the heads; and copula detection. We evaluate the impact the complex label analysis, where the copula re- of these approaches in computational pars- mains the head also, but the approach offers a dif- ing, in two parsing experiments for Hun- ferent solution to zero copulas. garian. First, we give a short description of Hungarian copula constructions. Second, the three depen- 1 Introduction dency syntactic frameworks are discussed in more Copula constructions show some special be- detail. Then, we describe two experiments aim- haviour in most human languages. In sentences ing to evaluate these frameworks in computational with copula constructions, the sentence’s predi- linguistics, specifically in dependency parsing for cate is not simply the main verb of the clause, Hungarian, similar to Nivre et al. -

Equative Constructions in World-Wide Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ZENODO 1 Equative constructions in world-wide perspective Martin Haspelmath & the Leipzig Equative Constructions Team1 Abstract: In this paper, we report on a world-wide study of equative constructions (‘A is as big as B’) in a convenience sample of 119 languages. From earlier work, it has been known that European languages often have equative constructions based on adverbial relative pronouns that otherwise express degree or manner (‘how’, ‘as’), but we find that this type is rare outside Europe. We divide the constructions that we found into six primary types, four of which have closely corresponding types of comparative constructions (‘A is bigger than B’). An equative construction often consists of five components: a comparee (‘A’), a degree-marker (‘as’), a parameter (‘is big’), a standard-marker (‘as’), and a standard (‘B’). Most frequently, the parameter is the main predicate and the equative sense is expressed by a special standard-marker. But many languages also have a degree-marker, so that we get a construction of the English and French type. Another possibility is for the equality sense to be expressed by a transitive ‘equal’ (or ‘reach’) verb, which may be the main predicate or a secondary predicate. And finally, since the equative construction is semantically symmetrical, it is also possible to “unify” the parameter and the standard in the subject position (‘A and B are equally tall’, or ‘A and B are equal in height’). But no language has only a degree-marker, leaving the standard unmarked. -

Theme’ in English: Their Syntax, Semantics and Discourse Functions

The Many Types of ‘Theme’ in English: their Syntax, Semantics and Discourse Functions Robin P. Fawcett The Many Types of ‘Theme’ in English: their Syntax, Semantics and Discourse Functions Robin P. Fawcett Emeritus Professor of Linguistics Cardiff University This book is being worked on, intermittently, so please forgive any inconsistencies of numbering, etc. I would be very grateful if you felt able to send me your comments and suggestions for improvements, including improvements in clarity. However, plans for publishing this work in this form in the near future have been shelved, as a result of the decision to focus on three other books: Fawcett forthcoming 2009a, forthcoming 2009b and forthcoming 2010 (for which see the References). The last of these will include material from the descriptive portion of the present work. I still intend to bring this work up to book- publishing standard at some point in the near future. Meanwhile I am happy for it to be used and cited, if you wish. CHANGES TO BE MADE Networks derived from Figure 2 will be added at appropriate points throughout. The figure numbers will be changed to start anew for each chapter. Notes comparing this approach with the networks in Halliday and Matthiessen 2004 and Thompson 2004 will be added (noting Thompson’s use of our term ‘enhanced’). Other possible changes (marked by XXX) will be considered. Perhaps I shall add the ‘fact’ that the word beginning with ‘t’ that was looked up most frequently on dictionary.com in 2005 was ‘theme’! Contents Preface 1 Introduction 1.1 Three -

The Origin of the Celtic Comparative Type Oir Tressa, MW

170 R. Schmitt 16: offenbar noch nicht erschienen 14. 17: Het'owm Patmic', Patmowt'iwn T'at'arac' [Hethum der Histori ker Geschichte der Tataren] / Getum Patmic, Istorija Tatar / Hetum Patmich, History of Tatars, 4°, 1981, [Vlj, 704 S. (T: Ven~tik 1842; ]3: The Origin of the Celtic Comparative Type Olr. tressa, Bambis Asoti Eganyan; 642-691 Wortliste, Namen und Datlerungen em MW Jrech 'stronger' scblieBend; 692-702 Namenliste). 18/1-2: Step'anos Taronec'i Asolik, Patmowt'iwn Tiezerakan [Stepha The comparison of adjectives in Celtic presents many interesting fea nos von Taraun Asolik, Universalgeschichte] / Stepanos TaroneCl AsohIi<, tures 1, Some of these are structural and grammatical, such as the restric Obscaja Istorija / Stepanos Taronetsi Asoghik, General History, 8', 1: tion of the comparative to predicative position and the introdnction of a A-E, 1987 15, [IV], 707 S.; 2: m:-M, 1987 15 , [IV], 683 S. (T: S. Peterburg fourth degree of comparison, the equative, beside the usual positive, 1885; B: Valarsak Arzowmani K 'osyan; I 658-666, II 638-645 Namenhste; comparative and superlative. But there are purely formal peculiarities as 1667-706, II 646--682 Wortliste)15. well. Irregularly compared adjectives are synchronically very conspicuous 19/1-2: Frik, Banastelcowt'yownner [Frik, Gedichte] / Frik, Stihotvo in Old Irish and Middle Welsh, and many of the individual irregularities renija / Frik, Poems, 8°,1: A-K, 1986, [IV], 598 S.; 2: H-F, 1987,482 S. that they display are also puzzling from a diachronic point of view. A case (T: Erevan 1941; B: DSxowhi Sowreni Movsisyan; R: Alek'sandr S~mom in point is the Old Irish comparative ending in -a, the origin of which has Margaryan; I 563, II 449 Namenliste; I 564-597, II 450-481 Worthste). -

Resulting Copulas and Their Complements in British and American English: a Corpus Based Study

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Martin Dokoupil anglická filologie & francouzská filologie Resulting Copulas and their Complements in British and American English: A Corpus Based Study. Bakalářská práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Mgr. Michaela Martinková, PhD. OLOMOUC 2011 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně na základě uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Olomouci, dne 10. srpna 2011 podpis 2 I hereby declare that this bachelor thesis is completely my own work and that I used only the cited sources. Olomouc, 10th August 2011 signature 3 Děkuji vedoucí mé bakalářské práce Mgr. Michaele Martinkové, PhD. za ochotu, trpělivost a cenné rady při psaní této práce. 4 Table of Contents: 1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................6 2 Theoretical Preliminaries ....................................................................................................7 2.1 Literature .....................................................................................................................7 2.2 Copular verb in general ..............................................................................................8 2.2.1 Copular verb .......................................................................................................8 2.2.2 Prototypical copular usage ...............................................................................8 2.2.3 Copular verb complementation