Copular Verbs of the Become Type and the Expression of ‘Resulting’ Meaning in English and in Czech: a Contrastive Corpus-Supported View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Syntactic Analysis of Copular Sentences*

A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF COPULAR SENTENCES* Masato Niimura Nanzan University 1. Introduction Copular is a verb whose main function is to link subjects with predicate complements. In a limited sense, the copular refers to a verb that does not have any semantic content, but links subjects and predicate complements. In a broad sense, the copular contains a verb that has its own meaning and bears the syntactic function of “the copular.” Higgins (1979) analyses English copular sentences and classifies them into three types. (1) a. predicational sentence b. specificational sentence c. identificational sentence Examples are as follows: (2) a. John is a philosopher. b. The bank robber is John Smith. c. That man is Mary’s brother. (2a) is an example of predicational sentence. This type takes a reference as subject, and states its property in predicate. In (2a), the reference is John, and its property is a philosopher. (2b) is an example of specificational sentence, which expresses what meets a kind of condition. In (2b), what meets the condition of the bank robber is John Smith. (2c) is an example of identificational sentence, which identifies two references. This sentence identifies that man and Mary’s brother. * This paper is part of my MA thesis submitted to Nanzan University in March, 2007. This paper was also presented at the Connecticut-Nanzan-Siena Workshop on Linguistic Theory and Language Acquisition, held at Nanzan University on February 21, 2007. I would like to thank the participants for the discussions and comments on this paper. My thanks go to Keiko Murasugi, Mamoru Saito, Tomohiro Fujii, Masatake Arimoto, Jonah Lin, Yasuaki Abe, William McClure, Keiko Yano and Nobuko Mizushima for the invaluable comments and discussions on the research presented in this paper. -

18.5 Complements Often, a Sub1ect and Verb Alone Can Express a Complete Thought. for Example, Buds Fly Can Stand by Itself As A

18.5 Complements Often, a sub1ect and verb alone can express a complete thought. For example, Buds fly can stand by itself as a sentence. Even though it contains only two words, a subject and a verb. Other times, however, the thought begun by a subject end its verb must be completed with other words. For example, Toni bought, The eyewitness told, Our mechanic is, Richard feels, and Marco seems all contain a subject and verb, but none expresses a complete thought. All these ideas need complements. 18.5.1: A complement is a word or group of words that completes the meaning of a sentence. Complements are usually nouns, pronouns, or adjectives. They are located right after or very close to the verb. The complements answer questions about the subject or verb in order to complete the sentence. S = SUBJECT, AV = ACTION VERB, LV = LINKING VERB, IO = INDIRECT OBJECT, DO = DIRECT OBJECT, PA = PREDICATE ADJECTIVE, PN = PREDICATE NOUN (NOMINATIVE) Toni bought cars. S – AV – DO. The eyewitness told us the story. S – AV – IO – DO. Our mechanic is a genius. S – LV- PN. Richard feels sad. S – LV – PA. Direct Objects 18.5.2 A direct object is a noun or pronoun that receives the action of a verb. You can find a direct object by asking What? or Whom? after an action verb. My dog Champ likes a good scratch. Like subjects and verbs, direct objects can be compound. That is, one verb can have two or more direct objects. Compound Direct Objects Like subjects and verbs, direct objects can be compound. -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

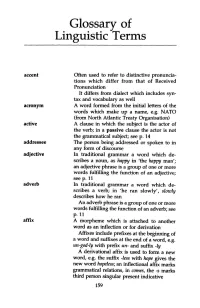

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional

Traditional Grammar Review Page 1 of 15 TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional grammar recognizes eight parts of speech: Part of Definition Example Speech noun A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. John bought the book. verb A verb is a word which expresses action or state of being. Ralph hit the ball hard. Janice is pretty. adjective An adjective describes or modifies a noun. The big, red barn burned down yesterday. adverb An adverb describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or He quickly left the another adverb. room. She fell down hard. pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. She picked someone up today conjunction A conjunction connects words or groups of words. Bob and Jerry are going. Either Sam or I will win. preposition A preposition is a word that introduces a phrase showing a The dog with the relation between the noun or pronoun in the phrase and shaggy coat some other word in the sentence. He went past the gate. He gave the book to her. interjection An interjection is a word that expresses strong feeling. Wow! Gee! Whew! (and other four letter words.) Traditional Grammar Review Page 2 of 15 II. Phrases A phrase is a group of related words that does not contain a subject and a verb in combination. Generally, a phrase is used in the sentence as a single part of speech. In this section we will be concerned with prepositional phrases, gerund phrases, participial phrases, and infinitive phrases. Prepositional Phrases The preposition is a single (usually small) word or a cluster of words that show relationship between the object of the preposition and some other word in the sentence. -

Syntax Topics • •

Syntax Topics 1. Syntax and morphology are the two parts of grammar. • Morphology deals with the internal economy of the word. • Syntax deals with the external economy of the word. 2. Words are constituents of larger groups, called phrases, which may aggregate into larger phrases, and eventually into a different kind of constituent, called a clause. 3. The difference between a phrase and a clause is that a phrase is focussed on one kind of word: a noun phrase (NP) is an elaboration of a noun, a verb phrase (VP) of a verb, etc; while a clause is a relation between two kinds of phrase: VP (Predi- cate) and NPs (Argument(s) of the Predicate). 4. Every sentence has at least one clause; many have more. If there are several, only one can be the main clause; the rest are subordinate clauses of one kind or another. 5. Grammatical functions expressed in many languages (called synthetic languages) by morphological inflection (e.g, tense, mood, voice, etc.) are expressed in English (an analytic language) by various syntactic constructions and augmentations, often using sets of special words called auxiliaries, particles, or function words. Such words include prepositions, conjunctions, quantifiers, and articles; sets of them are called closed classes, because they are small and don’t borrow new words. 6. The most important kind of word in any sentence is the matrix predicate, which in English can be a predicate adjective or predicate noun (with a form of be in front of it to receive the tense). The matrix predicate governs the type and existence of any subject, object, complement, or inflection appearing with it. -

Latin I Mastery List

LATIN I MASTERY LIST This is the information that you should know at the beginning of second year. We will spend a week or so reviewing – but it would be a good idea to go over this material before returning to school. NOUNS • Memorize endings of declensions 1-5, including neuters • Know that the genitive case gives the noun stem • Know the case usage: Nominative: subject, complement Genitive: possession (“of”) Dative: indirect object (“to/for”) Accusative: direct object, object of preposition Ablative: object of preposition, time when, time within which, means/ instrument, agent Vocative: direct address VERBS • Principal parts of four conjugations • Tenses – know how to recognize, translate and form Present Future Pluperfect Imperfect Perfect Future Perfect • Irregular verbs (all tenses) - sum, eo, fero • Imperative mood ADJECTIVES • 1st/2nd declension (us, a, um) and 3rd declension (is, is, e) • Agreement with nouns: gender, number and case PREPOSITIONS • Prepositions that take the accusative case: ad, in, per, post, prope, propter, apud • Prepositions that take the ablative case: a/ab, cum, de, e/ex, in, sine, sub SCHEMATIZING • Use declensions to accurately schematize (see attached sheet) SCHEMATIZING Schematizing involves: 1. breaking down the sentence into smaller parts 2. identifying the key parts of the sentence (verb/subject/direct object) verb = main verb of the clause noun/pron. and modifiers = subject or word related to subject noun/pron. and modifiers = direct object or word related to d. o. noun/pron. and modifiers = indirect object or word related to i. o. noun/pron. and modifiers = ablative (not in a prepositional phrase) noun/pron. and modifiers = complement/predicate nominative = pause in the sentence: colon, semicolon, comma, etc. -

Resulting Copulas and Their Complements in British and American English: a Corpus Based Study

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Martin Dokoupil anglická filologie & francouzská filologie Resulting Copulas and their Complements in British and American English: A Corpus Based Study. Bakalářská práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Mgr. Michaela Martinková, PhD. OLOMOUC 2011 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně na základě uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Olomouci, dne 10. srpna 2011 podpis 2 I hereby declare that this bachelor thesis is completely my own work and that I used only the cited sources. Olomouc, 10th August 2011 signature 3 Děkuji vedoucí mé bakalářské práce Mgr. Michaele Martinkové, PhD. za ochotu, trpělivost a cenné rady při psaní této práce. 4 Table of Contents: 1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................6 2 Theoretical Preliminaries ....................................................................................................7 2.1 Literature .....................................................................................................................7 2.2 Copular verb in general ..............................................................................................8 2.2.1 Copular verb .......................................................................................................8 2.2.2 Prototypical copular usage ...............................................................................8 2.2.3 Copular verb complementation -

RC HUMS 392 English Grammar and Meaning Complements

RC HUMS 392 English Grammar and Meaning Complements 1. Bill wanted/intended/hoped/said/seemed/forgot/asked/failed/tried/decided to write the book. 2. Bill enjoyed/tried/finished/admitted/reported/remembered/permitted writing the book. 3. Bill thought/said/forgot/remembered/reported/was sad/discovered/knew that he wrote the book. 4. Bill asked/wondered/knew/discovered/said why he wrote the book. There are four different types of complement (noun clause, either subject or object – the ones above are all object complements): respectively, they are called infinitive, gerund, that-clause, and embedded question. These types, and their structures and markers (like to and –ing) are often called complementizers. Other names for these types include for-to complementizer (infinitive), POSS-ing (or ACC-ing) complementizer (gerund), inflected (or tensed) clause (that), or WH- complementizer (embedded question). Which term you use is of no concern; they’re equivalent. Infinitives and gerunds are often called non-finite clauses, while questions and that-clauses are called finite clauses, because of the absence or presence of tense markers on the verb form. That-clauses and questions must have a fully-inflected verb, in either the present or past tense, while infinitives and gerunds are not marked for tense. Non-finite complements often do not have overt subjects; these may be deleted either because they’re indefinite or under identity. Very roughly speaking, infinitives refer to states, gerunds to events or activities, and that-clauses to propositions, but it is the identify and nature of the matrix predicate governing the complement (i.e, the predicate that the complement is the subject or object of) that determines not only what kind of thing the complement refers to, but also whether there can be a complement at all, and which complementizer(s) it can take, if so. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

Interrogating Possessive Have: a Case Study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó

99 József Andor: Interrogating possessive have: a case study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó József Andor Interrogating possessive have: a case study Abstract Major, standard grammars of English give an account and interpret interrogatively used possessive have as a unique specialty of genres and text types of British English. Reviewing descriptions offered by some of these grammars and presenting empirically based evidence on acceptability of usage and function, the present paper offers results revealing the occurrence of inverted possessive have in other regional varieties, specifically in American English. It is suggested that have, retaining its possessive lexical meaning behaves as a semi-auxiliary in such constructions. Keywords: possessive, inversion, do-support, corpus-based, semi-auxiliary, notionally and morpho-syntactically based categorization 1 Introduction What made me start researching the functional-semantic and pragmatic-contextual force of interrogative sentences with the possessive lexical status of have was finding the example Have you a pen? on page 88 of the recently published Oxford Modern English Grammar authored by Bas Aarts (2011). The sentence was given under section 4.1.1.6. titled “Subjects invert positions with verbs in interrogative main clauses”, which section, due to its scope, did not address discussing syntactic variation concerning possessive usage of have, contrasting syntactic as well as cognitive-semantic and pragmatic, usage based issues of formally pure cases of inversion with the co-occurrence of have and do-support (also called do-periphrasis) or the have got construction. This came to me as a surprise, as types of have-based possession could have been discussed in a dictionary based on one of the most valuable corpora of British English, the British component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB).