Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

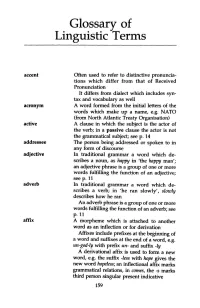

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram. -

Modals and Auxiliaries 12

Verbs: Modals and Auxiliaries 12 An auxiliary is a helping verb. It is used with a main verb to form a verb phrase. For example, • She was calling her friend. Here the word calling is the main verb and the word was is an auxiliary verb. The words be , have , do , can , could , may , might , shall , should , must , will , would , used , need , dare , ought are called auxiliaries . The verbs be, have and do are often referred to as primary auxiliaries. They have a grammatical function in a sentence. The rest in the above list are called modal auxiliaries, which are also known as modals. They express attitude like permission, possibility, etc. Note the forms of the primary auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs Present tense Past tense be am, is, are was, were do do, does did have has, have had The table below illustrates the application of these primary verbs. Primary auxiliary Function Example used in the formation of She is sewing a dress. continuous tenses I am leaving tomorrow. be in sentences where the The missing child was action is more important found. than the subject 67 EBC-6_Ch19.indd 67 8/12/10 11:47:38 PM when followed by an We are to leave next infinitive, it is used to week. indicate a plan or an arrangement denotes command You are to see the Principal right now. used to form the perfect The carpenter has tenses worked well. have used with the infinitive I had to work that day. to indicate some kind of obligation used to form the He doesn’t work at all. -

The Production of Finite and Nonfinite Complement Clauses by Children with Specific Language Impairment and Their Typically Developing Peers

The Production of Finite and Nonfinite Complement Clauses by Children With Specific Language Impairment and Their Typically Developing Peers Amanda J. Owen University of Iowa, Iowa City The purpose of this study was to explore whether 13 children with specific language Laurence B. Leonard impairment (SLI; ages 5;1–8;0 [years;months]) were as proficient as typically developing age- and vocabulary-matched children in the production of finite and Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN nonfinite complement clauses. Preschool children with SLI have marked difficulties with verb-related morphology. However, very little is known about these children’s language abilities beyond the preschool years. In Experiment 1, simple finite and nonfinite complement clauses (e.g., The count decided that Ernie should eat the cookies; Cookie Monster decided to eat the cookies) were elicited from the children through puppet show enactments. In Experiment 2, finite and nonfinite complement clauses that required an additional argument (e.g., Ernie told Elmo that Oscar picked up the box; Ernie told Elmo to pick up the box) were elicited from the children. All 3 groups of children were more accurate in their use of nonfinite complement clauses than finite complement clauses, but the children with SLI were less proficient than both comparison groups. The SLI group was more likely than the typically developing groups to omit finiteness markers, the nonfinite particle to, arguments in finite complement clauses, and the optional complementizer that. Utterance-length restrictions were ruled out as a factor in the observed differences. The authors conclude that current theories of SLI need to be extended or altered to account for these results. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

Interrogating Possessive Have: a Case Study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó

99 József Andor: Interrogating possessive have: a case study Argumentum 9 (2013), 99-107 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó József Andor Interrogating possessive have: a case study Abstract Major, standard grammars of English give an account and interpret interrogatively used possessive have as a unique specialty of genres and text types of British English. Reviewing descriptions offered by some of these grammars and presenting empirically based evidence on acceptability of usage and function, the present paper offers results revealing the occurrence of inverted possessive have in other regional varieties, specifically in American English. It is suggested that have, retaining its possessive lexical meaning behaves as a semi-auxiliary in such constructions. Keywords: possessive, inversion, do-support, corpus-based, semi-auxiliary, notionally and morpho-syntactically based categorization 1 Introduction What made me start researching the functional-semantic and pragmatic-contextual force of interrogative sentences with the possessive lexical status of have was finding the example Have you a pen? on page 88 of the recently published Oxford Modern English Grammar authored by Bas Aarts (2011). The sentence was given under section 4.1.1.6. titled “Subjects invert positions with verbs in interrogative main clauses”, which section, due to its scope, did not address discussing syntactic variation concerning possessive usage of have, contrasting syntactic as well as cognitive-semantic and pragmatic, usage based issues of formally pure cases of inversion with the co-occurrence of have and do-support (also called do-periphrasis) or the have got construction. This came to me as a surprise, as types of have-based possession could have been discussed in a dictionary based on one of the most valuable corpora of British English, the British component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB). -

*65 EØ RS Mitipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P

1100&*430 ERIC RE PeRT .RESUNE IEO 010 -t-60 1W,29Hib 24 (REV) USSGE IIANUAL:44LANGUAGE CUUICIMUK. I AND !I TEACHER V ER&Iet4, ZHAER4ALURTAWR RaR610280 UNC.VERSITY OE ORE?, -EUGENE Cit9+1*114114411 1111409,40116.C431 . *65 EØ RS MiTipse1e9tticaasa.56 9P. *GRAMM-0..111GhTH- IIRAINEV.- sevens .'GRADEs. vitiCIINUCAILOCSUIDESS *TIEAZINING- SUIDESL 11-YEAL4IVIL 61/10Ett. TiENGLISK EWEN/v; MESONV4-PROJECIr'ENG11314-- RE* GRAM* A IIANUSL, GRINAR- WAGE WAS PRIEN*.f.a *OR- -TEACHINC,1semoffspoi, AND EIGHTIWERMSE- MOMS .CARINECULUNS.- THEP-MANUAt 11111S44R,-TEAT;NERWAIND CONTAINS1 96 ' GRIMMAR_ USAGEWITEett -*WOE 4-1111111), 4ItykiPROF1TSO1Y,-:TRENNIED: .4N SENENTWAID: E IGHTW GRAvegq: THE7COIITEInt-41ave-litst ,i4MIANGEO- ALAINACITICALLY-41101 A GAUt MOM '41F- -CROSSMIEFERENEU,-311EIMINUAL -414--STIODENT 4111.11NADVE_':OP-.4=UNISSORMATI.-4.14AL'IMAPSIAL--Te MEGRIM: -47 NTH SUER- -ALIPECTS 1iI E 1INGUSH 7CURRICARAIMIAN ACCOMPANYING MANUAL WAS ?NEPA-RED FOR -STUOEUT USE :4110,-010 :ant; IMO el OREGON etlittfAcilLatIM 5.xuuY CINTER **0 014 VELEM IL SiDEPARTMENT OFHEMplti: MICATION v-4 Office cif Echkgati On d**filthy has beenreproduced exactlyslitectile Co This document Points Of VieW OrOPielone organizationoriginating It. v-1 person or represent OMNIOff Ice etEducation stated donot necessarily CI position or policy. C) I USAGE ISAIWATe !ammo Curriculum I Mid II Teacher I/onion The project reported hereinwas -supported through the Cooperative ResearchPrograxa of- the Office of Education, U, S. Departgle4totilealt4s Education, and Welfare USAGE MANUAL TABLE OFCONTENTS Etas Abbreviations 1 Bust for burst Accent- Except 3. CapitalCapitol a Adjective 1 Capitalization 9 Adverb 2 Case 10 I Advice- Advise 2 clothsClothes 11 Affect- Effect 3 Colon 11 Agreement 3 Comma 11 Ain't 5 Almost-Most' 5 ConjUnction 11 Already-All ready 5 Contractions 12 All right 5 tOundil- Counsel 12 Altogether - All together 5 toUrse-Coarse 12 Among- Between 6 DetertDessert 12 ft.n-And 6 Determiner 13 Antecedent 6 ed -bove 13 t Apostrophe 6 Done foi-' did 18 Appositive 7 Negative 14 s. -

Verbnet Guidelines

VerbNet Annotation Guidelines 1. Why Verbs? 2. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource 3. VerbNet Contents a. The Hierarchy b. Semantic Role Labels and Selectional Restrictions c. Syntactic Frames d. Semantic Predicates 4. Annotation Guidelines a. Does the Instance Fit the Class? b. Annotating Verbs Represented in Multiple Classes c. Things that look like verbs but aren’t i. Nouns ii. Adjectives d. Auxiliaries e. Light Verbs f. Figurative Uses of Verbs 1 Why Verbs? Computational verb lexicons are key to supporting NLP systems aimed at semantic interpretation. Verbs express the semantics of an event being described as well as the relational information among participants in that event, and project the syntactic structures that encode that information. Verbs are also highly variable, displaying a rich range of semantic and syntactic behavior. Verb classifications help NLP systems to deal with this complexity by organizing verbs into groups that share core semantic and syntactic properties. VerbNet (Kipper et al., 2008) is one such lexicon, which identifies semantic roles and syntactic patterns characteristic of the verbs in each class and makes explicit the connections between the syntactic patterns and the underlying semantic relations that can be inferred for all members of the class. Each syntactic frame in a class has a corresponding semantic representation that details the semantic relations between event participants across the course of the event. In the following sections, each component of VerbNet is identified and explained. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource VerbNet is a lexicon of approximately 5800 English verbs, and groups verbs according to shared syntactic behaviors, thereby revealing generalizations of verb behavior. -

TAV of English Finite Verb Phrase

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2018, Vol. 8, No. 7, 1126-1130 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.07.019 D DAVID PUBLISHING TAV of English Finite Verb Phrase Peter Lung-shan CHUNG University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China It is widely known that a finite verb phrase (fVP) of a clause in English consists of three components: tense, aspect and voice. While the two tenses, present and past, and the two voices, active and passive, are recognized and generally agreed, the number and constituents of aspects may not be so simple and they are open to dispute. This paper proposes that a new aspect, the “modal” aspect, be included in addition to the commonly recognized ones, namely “simple”, “perfect” and “continuous” (also known as “progressive”). With the inclusion of the “modal” aspect, there are four single aspects: “simple”, “modal”, “perfect” and “continuous”. They can be combined to form multiple aspects according to the aforesaid sequence. The “modal” aspect is realized with a modal verb (any ofthe modal verbs will/would, shall/should, can/could, may/might, must, ought to, used to and the two semi-modals, “need” and “dare” in interrogative and negative structures). Whenever a modal verb is used, the verb phrase is in the modal aspect. The modal verb to be used is for the interlocutor to decide and falls beyond this discussion, which focuses on the structure of the fVP of the English language. The two tenses, eight aspects and two voices (active and passive) make up the 32 TAVs (an acronym formed with “Tense”, “Aspect” and “Voice”) of the English fVP. -

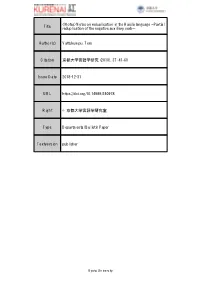

Title <Notes>Notes on Reduplication in the Haisla Language --Partial

<Notes>Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language --Partial Title reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb-- Author(s) Vattukumpu, Tero Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2018), 37: 41-60 Issue Date 2018-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/240978 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 37 (2018), 41 –60 Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language Ü Partial reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb Ü Tero Vattukumpu Abstract: In this paper I will point out that, according to my data, a plural form of the negative auxiliary verb formed by means of partial reduplication exists in the Haisla language in contrary to a description on the topic in a previous study. The plural number of the subject can, and in many cases must, be indicated by using a plural form of at least one of the components of the predicate, i.e. either an auxiliary verb (if there is one), the semantic head of the predicate or both. Therefore, I have examined which combinations of the singular and plural forms of the negative auxiliary verb and different semantic heads of the predicate are judged to be acceptable by native speakers of Haisla. My data suggests that – at least at this point – it seems to be impossible to make convincing generalizations about any patterns according to which the acceptability of different combinations could be determined *. Keywords: Haisla, partial reduplication, negative auxiliary verb, plural, root extension 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce some preliminary notes about reduplication in the Haisla language from a morphosyntactic point of view as a first step towards a better understanding and a more comprehensive analysis of all the possible patterns of reduplication in the language.