Modals and Auxiliaries 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grammar Workshop Verb Tenses

Grammar Workshop Verb Tenses* JOSEPHINE BOYLE WILLEM OPPERMAN ACADEMIC SUPPORT AND ACCESS CENTER AMERICAN UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 29, 2 0 1 6 *Sources consulted: Purdue OWL and Grammarly Handbook What is a Verb? Every basic sentence in the English language must have a noun and a verb. Verbs are action words. Verbs describe what the subject of the sentence is doing. Verbs can describe physical actions like movement, less concrete actions like thinking and feeling, and a state of being, as explained by the verb to be. What is a Verb? There are two specific uses for verbs: Put a motionless noun into motion, or to change its motion. If you can do it, its an action verb. (walk, run, study, learn) Link the subject of the sentence to something which describes the subject. If you can’t do it, it’s probably a linking verb. (am, is) Action Verbs: Susie ran a mile around the track. “Ran” gets Susie moving around the track. Bob went to the book store. “Went” gets Bob moving out the door and doing the shopping at the bookstore. Linking Verbs: I am bored. It’s difficult to “am,” so this is likely a linking verb. It’s connecting the subject “I” to the state of being bored. Verb Tenses Verb tenses are a way for the writer to express time in the English language. There are nine basic verb tenses: Simple Present: They talk Present Continuous: They are talking Present Perfect: They have talked Simple Past: They talked Past Continuous: They were talking Past Perfect: They had talked Future: They will talk Future Continuous: They will be talking Future Perfect: They will have talked Simple Present Tense Simple Present: Used to describe a general state or action that is repeated. -

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram. -

The Syntax of Simple and Compound Tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko*

Proc Ling Soc Amer Volume 1, Article 18:1-15 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v1i0.3716 The Syntax of simple and compound tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko* Abstract. It is a widely accepted generalization that verbal periphrasis is triggered by in- creased inflectional meaning and a paucity of verbal elements to support its realization. This work examines the limitations on synthetic verbal forms in Ndebele and argues that periphrasis in this language arises via a last-resort grammatical mechanism. The proposed trigger of auxiliary insertion is c-selection – a relation between inflectional categories and verbs. Keywords. verbal periphrasis; default auxiliary; c-selection; Ndebele; Bantu 1. Introduction. This paper focuses on the mechanics of default periphrasis – a phenomenon where a default verb (an auxiliary) appears in a complex inflectional context. I provide an anal- ysis of two types of compound tenses in Ndebele:1 Perfect and Prospective tenses, arguing that periphrastic expressions in those tenses are triggered by c-selectional features on T heads. The type of verbal periphrasis we find in Ndebele is known as the overflow pattern of auxiliary use (Bjorkman, 2011), and is illustrated in (1),2 where Present Perfect and Simple Future are synthetic (there is no auxiliary), but Future Perfect is periphrastic (1-c). (1) Default periphrasis in Ndebele: a. U- ∅- dl -ile Present Perfect/Recent Past (synthetic) 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You have eaten/you ate recently’. b. U- za- dl -a Simple Future (synthetic) 2sg- FUT- eat -FS ‘You will eat’. c. U- za- be u- ∅- dl -ile Future Perfect (periphrastic) 2sg- FUT- aux 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You will have eaten’. -

Evidence from the Spanish Present Tense Julio Cesar Lopez Otero Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Theses Theses and Dissertations 4-2016 Bilingualism effects at the syntax-semantic interface: Evidence from the Spanish present tense Julio Cesar Lopez Otero Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses Part of the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Lopez Otero, Julio Cesar, "Bilingualism effects at the syntax-semantic interface: Evidence from the Spanish present tense" (2016). Open Access Theses. 789. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/789 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 12/26/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Julio César López Otero Entitled BILINGUALISM EFFECTS AT THE SYNTAX-SEMANTICS INTERFACE: EVIDENCE FROM THE SPANISH PRESENT TENSE For the degree of Master of Arts Is approved by the final examining committee: Alejandro Cuza-Blanco Chair Daniel J. Olson Mariko Wei To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Alejandro Cuza-Blanco Approved by: Madeleine Henry 4/18/2016 Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date ! i! BILINGUALISM EFFECTS AT THE SYNTAX-SEMANTIC INTERFACE: EVIDENCE FROM THE SPANISH PRESENT TENSE A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Julio César López Otero In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2016 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ! ii! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Quisiera agradecer a todas las personas que me han ayudado a terminar esta tesis. -

Verb Tense NC State Writing and Speaking Tutorial Services ∗ NC State Graduate Writing Center Go.Ncsu.Edu/Wsts ∗ 919.515.3163 ∗ Go.Ncsu.Edu/Gwc

Verb Tense NC State Writing and Speaking Tutorial Services ∗ NC State Graduate Writing Center go.ncsu.edu/wsts ∗ 919.515.3163 ∗ go.ncsu.edu/gwc Introduction English verb tenses tell when an action took place, whether or not it ended, and what effect it has on a situation. There are three basic time periods when actions can occur (past, present, and future) and four aspects (simple, perfect, progressive, and perfect progressive). When combined, the resulting tenses give information about the action in a sentence. The chart below gives examples of the results of these combinations: Simple Perfect Progressive Perfect Progressive Past Arrived Had arrived Was/were arriving Had been arriving Present Arrive Has/have arrived Am/is/are arriving Has/have been arriving Future Will arrive Will have arrived Will be arriving Will have been arriving Note: You may have noticed that many of these tenses have additional words (e.g., had, am, will) preceding them. These are known as auxiliaries, and are used to form many English verb tenses. In fact, only two English verb tenses (simple past and simple present) do not use auxiliaries. Simple Tenses: Simple tenses convey a sense of a completed action without strict regard to time or when the action began or ended. Perfect Tenses: Unlike the simple tenses, the perfect tenses do indicate a relationship between two points in time such as a relationship between a past action and present circumstances. For perfect tenses, the action taken is finite: it has ended or will end. Progressive Tenses: In the progressive tenses, an action is still occurring or is otherwise incomplete, and the tense may not indicate when the action will end. -

Constructions and Result: English Phrasal Verbs As Analysed in Construction Grammar

CONSTRUCTIONS AND RESULT: ENGLISH PHRASAL VERBS AS ANALYSED IN CONSTRUCTION GRAMMAR by ANNA L. OLSON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Linguistics, Analytical Stream We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Emma Pavey, PhD; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Sean Allison, Ph.D.; Second Reader ................................................................................ Dr. David Weber, Ph.D.; External Examiner TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY September 2013 © Anna L. Olson i Abstract This thesis explores the difference between separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs, focusing on finding a reason for the non-separable verbs’ lack of compatibility with the word order alternation which is present with the separable phrasal verbs. The analysis is formed from a synthesis of ideas based on the work of Bolinger (1971) and Gorlach (2004). A simplified version of Cognitive Construction Grammar is used to analyse and categorize the phrasal verb constructions. The results indicate that separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs are similar but different constructions with specific syntactic reasons for the incompatibility of the word order alternation with the non-separable verbs. ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... -

1 Regular Verbs Simple Present, Simple Past and Present Perfect

Regular Verbs with sound of /t/ Regular Verbs Simple Present, Simple Past and Present Perfect Tenses This is a list of Regular Verbs. These verbs use -ed for the simple past tense and the past participle. The –ed ending sounds like /t/ I will read the base form, the simple past tense and the past participle of the verb. Then, I will read the verb in three sentences, a simple present tense sentence, a simple past tense sentence and a present perfect tense sentence. There will be time for you to repeat the verbs and sentences. Try it, it is good practice! Base Past Past Participle Sentences Ask asked asked Simple present tense The teacher asks questions every day. Simple past tense The teacher asked questions yesterday. Present perfect tense The teacher has asked questions since class began. Bake baked baked Simple present tense She bakes a cake every week. Simple past tense She baked a cake last night. Present perfect tense She has baked a cake every week for many years. Cook cooked cooked Simple present tense I cook dinner every night. Simple past tense I cooked dinner last night. Present perfect tense I have cooked dinner every night for two weeks. Cough coughed coughed Simple present tense Abdullahi coughs a lot because he is sick. Simple past tense Abdullahi coughed a lot because he was sick. Present perfect tense Abdullahi has coughed a lot for almost a week. Clap clapped clapped Simple present tense The children always clap their hands. Simple past tense The children clapped their hands 10 minutes ago. -

Verbnet Guidelines

VerbNet Annotation Guidelines 1. Why Verbs? 2. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource 3. VerbNet Contents a. The Hierarchy b. Semantic Role Labels and Selectional Restrictions c. Syntactic Frames d. Semantic Predicates 4. Annotation Guidelines a. Does the Instance Fit the Class? b. Annotating Verbs Represented in Multiple Classes c. Things that look like verbs but aren’t i. Nouns ii. Adjectives d. Auxiliaries e. Light Verbs f. Figurative Uses of Verbs 1 Why Verbs? Computational verb lexicons are key to supporting NLP systems aimed at semantic interpretation. Verbs express the semantics of an event being described as well as the relational information among participants in that event, and project the syntactic structures that encode that information. Verbs are also highly variable, displaying a rich range of semantic and syntactic behavior. Verb classifications help NLP systems to deal with this complexity by organizing verbs into groups that share core semantic and syntactic properties. VerbNet (Kipper et al., 2008) is one such lexicon, which identifies semantic roles and syntactic patterns characteristic of the verbs in each class and makes explicit the connections between the syntactic patterns and the underlying semantic relations that can be inferred for all members of the class. Each syntactic frame in a class has a corresponding semantic representation that details the semantic relations between event participants across the course of the event. In the following sections, each component of VerbNet is identified and explained. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource VerbNet is a lexicon of approximately 5800 English verbs, and groups verbs according to shared syntactic behaviors, thereby revealing generalizations of verb behavior. -

A New Syntax Theory

VOLUME 9 | SPRING 2020 PARTICIPANT BAR THEORY: A NEW SYNTAX THEORY Daniel M. Packer & Michael Hamilton Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters Abstract in the present tense and past tense, I first present the syntactic differences between the present tense and past I endeavor to introduce, justify, and ultimately tense in Welsh. After an explanation of the differences persuade for acceptance of a new syntax theory titled in syntactic structure between present tense and past “Participant Bar Theory.” In order to understand the tense sentences in Cymraeg, I explain the morphological purpose of Participant Bar Theory, it is essential to formation of verbs, provide definitions of subject have an understanding of the inherent issues of X-bar pronouns, and discuss the relationship between the verb Theory. Also, an introductory-level understanding of and subject. Finally, I will present a new syntactic tree the morphology and syntax of simple present tense and structure, which I name “syntantic tree.” This structure, simple past tense of Welsh will serve the reader well, which is the visual representation of this new syntactic for Welsh will be the language with which I will defend theory, which I name “Participant Bar Theory,” proposes Participant Bar Theory. This paper will also introduce a synthesis of verb-topicalization and participant a new term, which I have coined as “syntantics,” a acknowledgement in order to account for the VSO word blending of “syntax” and “semantics,” for the purpose order in all Welsh tenses, except for the present tense. of rationalizing Participant Bar Theory. This paper will show two syntantic trees (Figures 8 and 9) that illustrate To present the basics of Cymraeg syntax, I the past tense. -

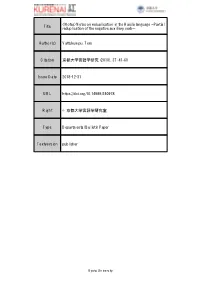

Title <Notes>Notes on Reduplication in the Haisla Language --Partial

<Notes>Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language --Partial Title reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb-- Author(s) Vattukumpu, Tero Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2018), 37: 41-60 Issue Date 2018-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/240978 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 37 (2018), 41 –60 Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language Ü Partial reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb Ü Tero Vattukumpu Abstract: In this paper I will point out that, according to my data, a plural form of the negative auxiliary verb formed by means of partial reduplication exists in the Haisla language in contrary to a description on the topic in a previous study. The plural number of the subject can, and in many cases must, be indicated by using a plural form of at least one of the components of the predicate, i.e. either an auxiliary verb (if there is one), the semantic head of the predicate or both. Therefore, I have examined which combinations of the singular and plural forms of the negative auxiliary verb and different semantic heads of the predicate are judged to be acceptable by native speakers of Haisla. My data suggests that – at least at this point – it seems to be impossible to make convincing generalizations about any patterns according to which the acceptability of different combinations could be determined *. Keywords: Haisla, partial reduplication, negative auxiliary verb, plural, root extension 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce some preliminary notes about reduplication in the Haisla language from a morphosyntactic point of view as a first step towards a better understanding and a more comprehensive analysis of all the possible patterns of reduplication in the language. -

4 the Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion

Introduction to Configurational Syntax Chapter 4 : Chapter 4. 4 The Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion 4.1 Introduction In this chapter the sentence and the verb (predicate) phrase whose head is an auxiliary verb are formally introduced. These two categories do not appear to follow the universal expansion of XP proposed in Chapter 2. In the Principles and Parameters framework of syntax the structure of the sentence can be shown to fol- low the universal expansion of XP. However, the analysis of the sentence given the category CP1 is considered too complex to be covered here. The analyses given here follow the earlier standard views on the structure of the sentence. 4.2 The Sentence At first glance, note that the sentence contains a NP and a VP: (297)a. The moon orbits around the earth. b. [NP the moon ] [VP orbits around the earth ]. We can state the expansion of S (sentence) as: (298) The Expansion of S [1] S ˘ NP VP. The structure for (297 is: (299) [S [NP The moon ] [VP orbits around the earth]] Up to this point we have claimed that all constituents contain a head and a complement. If this is the case then what is the head of S? In advanced work it can be shown to be either tense in some points of view, or the verb in other points of view. In some sense both points of view or correct; however, it is too complex a matter to attempt to explain this here. We will adopt the above expansion, which is traditional and found in most texts, and note that the verb is the unexplained head of the sentence. -

Verb Phrase, Or VP

VP Study Guide In the Logic Study Guide, we ended with a logical tree diagram for WANT (BILL, LEAVE (MARY)), in both unlabelled: WANT BILL LEAVE MARY and labelled versions: P WANT BILL P LEAVE MARY We remarked that one could label the Predicate and Argument nodes as well, and that it was common to use S instead of P to label propositions in such logical tree structures in linguistics. It is also com- mon, in practice, to use V to label Predicates, and N (or NP, standing for Noun Phrase) to label Ar- guments. This would produce the following diagram: S V NP NP Subject Formation WANT BILL S V NP LEAVE MARY Note that, while these two predicates are in fact verbs, and the arguments are nouns, that’s not always the case, and one may use V loosely to label any Predicate node, whatever its syntactic class might be. This kind of structural description, intermediate between logic and surface syntax, is called a deep structure; we say this diagram represents the deep structure of Bill wants Mary to leave. Roughly speaking, deep structures are intended to represent the meaning of the sentence, stripped to its essentials. The deep structures are then related to the actual sentence by a series of relational rules. For instance, one such rule is that in English, there must be a subject NP, and it precedes the verb, instead of coming after it, as here. So we relate this structure with the following one by a rule of Subject Formation, which applies to every deep structure towards the end of the derivation (the series of rule applications; a number of other rules would have already applied earlier, producing the other differences).