4 the Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Differences in the Use of Modal Adverbs As Hedges

FACULTY OF EDUCATION AND BUSINESS STUDIES Department of Humanities Gender differences in the use of modal adverbs as hedges Reyyan Ayhan 2020 Student thesis, Bachelor degree, 15 HE English Upper Secondary Teacher Education Programme English 61-90 HE Supervisor: Henrik Kaatari Examiner: Kavita Thomas Table of contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Aim and research questions ......................................................................................... 3 2 Theoretical Background .................................................................................. 3 2.1 Language and gender ................................................................................................... 3 2.1.1 Women’s language and politeness ....................................................................... 4 2.2 Grammatical background ............................................................................................ 8 2.2.1 Definition of hedges ............................................................................................. 8 2.2.2 Modality and modal adverbs ................................................................................ 9 2.2.2.1 Categorisation of modal adverbs .................................................................... 11 2.2.2.2 Placement of modal adverbs ........................................................................... 12 3 Material and method ..................................................................................... -

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram. -

Modal Verbs Can, May and Must and Semi-Modal Ought to in Spoken

Modal verbs can, could, may, might, should and must and semi-modals ought to and have to in spoken Scottish English as compared to spoken English English Suvi Myllyniemi University of Tampere School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies English Language and Literature MA Thesis November 2015 Tampereen yliopisto Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö Englannin kieli ja kirjallisuus MYLLYNIEMI, SUVI: Modal verbs can, could, may, might, should and must and semi-modals ought to and have to in spoken Scottish English as compared to spoken English English Pro gradu -tutkielma, 64 s. Marraskuu 2015 Tämä pro gradu –tutkielma tarkastelee modaaliapuverbien can, could, may, might, should ja must sekä semimodaalien ought to ja have to käyttöä puhutussa skotti- ja englanninenglannissa vertaillen näitä keskenään siten että pääpaino on skottienglannissa. Tarkoituksena on selvittää, missä suhteessa kukin modaaliapuverbi tai semimodaali edustaa kutakin kolmesta modaalisuuden tyypistä, joihin kuuluvat episteeminen, deonttinen sekä dynaaminen modaalisuus. Skottienglanti-nimitystä käytetään yläkäsitteenä kattamaan Skotlannissa esiintyvät kielen varieteetit skotista Skotlannin standardienglantiin. Koska sen sisältö on niinkin laaja, on sen tarkka määritteleminen monimutkaista. Skottienglannin modaalijärjestelmän on todettu eroavan melko suurestikin englanninenglannin vastaavasta, ja tämä tutkielma pyrkii osaltaan valaisemaan sitä, onko tilanne todellakin näin. Teoria- ja metodiosuus tarkastellaan ensin tutkielman teoreettista viitekehystä, -

Modals and Auxiliaries 12

Verbs: Modals and Auxiliaries 12 An auxiliary is a helping verb. It is used with a main verb to form a verb phrase. For example, • She was calling her friend. Here the word calling is the main verb and the word was is an auxiliary verb. The words be , have , do , can , could , may , might , shall , should , must , will , would , used , need , dare , ought are called auxiliaries . The verbs be, have and do are often referred to as primary auxiliaries. They have a grammatical function in a sentence. The rest in the above list are called modal auxiliaries, which are also known as modals. They express attitude like permission, possibility, etc. Note the forms of the primary auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs Present tense Past tense be am, is, are was, were do do, does did have has, have had The table below illustrates the application of these primary verbs. Primary auxiliary Function Example used in the formation of She is sewing a dress. continuous tenses I am leaving tomorrow. be in sentences where the The missing child was action is more important found. than the subject 67 EBC-6_Ch19.indd 67 8/12/10 11:47:38 PM when followed by an We are to leave next infinitive, it is used to week. indicate a plan or an arrangement denotes command You are to see the Principal right now. used to form the perfect The carpenter has tenses worked well. have used with the infinitive I had to work that day. to indicate some kind of obligation used to form the He doesn’t work at all. -

Catenative Verbs

Catenative verbs The following lists do not consider marginal, semi- or pure modal auxiliary verbs. Verbs followed by the to-infinitive In nearly all cases, the use of the to-infinitive signals that the event represented by the main verb takes place before that represented by the following verb(s). In other words, the use is prospective rather than retrospective. This is not an absolute rule but is certainly the way to bet. For example, if one says: I agreed to come then the agreeing clearly precedes the coming. This rule of thumb applies even when the following action is unfulfilled as in, e.g.: I declined to go with them because even here, the declining precedes the not going. The following are the most common of these verbs with some notes where necessary. Verb Example Notes advise He advised me to try This verb is almost invariably used with a direct object. Almost invariably with can. This verb takes a noun as a direct object but not a gerund so we allow: afford We can afford to buy the car We can afford a new car but not *We can afford going on holiday In AmE usage, this verb is transitive and that is becoming common in BrE, too so we allow also: agree They agreed to differ We agreed the plan. However, like afford, a gerund as the object is not allowed. This is akin to We aim to take a winter aim We are going to take a winter holiday holiday and is a prospective use. The verb let takes the bare infinitive (see below). -

Modal Verbs in English Grammar

Modal Verbs in English Grammar Adapted from https://english.lingolia.com/ What is a modal verb? The modal verbs in English grammar are: can, could, may, might, must, need not, shall/will, should/ought to. They express things like ability, permission, possibility, obligation etc. Modal verbs only have one form. They do not take -s in the simple present and they do not have a past simple or past participle form. However, some modal verbs have alternative forms that allow us to express the same ideas in different tenses. Example Max’s father is a mechanic. He might retire soon, so he thinks Max should work in the garage more often. Max can already change tires, but he has to learn a lot more about cars. Max must do what he is told and must not touch any dangerous equipment. Conjugation of English Modal Verbs There are a few points to consider when using modal verbs in a sentence: Modal verbs are generally only used in the present tense in English but we don’t add an -s in the third person singular. Example: He must do what he is told. (not: He musts …) Modal verbs do not take an auxiliary verb in negative sentences and questions. Example: Max need not worry about his future. Max must not touch any dangerous equipment. Can Max change a tire? We always use modal verbs with a main verb (except for short answers and question tags). The main verb is used in the infinitive without to. Example: Max can change tires. (not: Max can to change tires.) Usage We use modal verbs to express ability, to give advice, to ask for and give permission, to express obligation, to express possibility, to deduce and to make predictions. -

Verbnet Guidelines

VerbNet Annotation Guidelines 1. Why Verbs? 2. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource 3. VerbNet Contents a. The Hierarchy b. Semantic Role Labels and Selectional Restrictions c. Syntactic Frames d. Semantic Predicates 4. Annotation Guidelines a. Does the Instance Fit the Class? b. Annotating Verbs Represented in Multiple Classes c. Things that look like verbs but aren’t i. Nouns ii. Adjectives d. Auxiliaries e. Light Verbs f. Figurative Uses of Verbs 1 Why Verbs? Computational verb lexicons are key to supporting NLP systems aimed at semantic interpretation. Verbs express the semantics of an event being described as well as the relational information among participants in that event, and project the syntactic structures that encode that information. Verbs are also highly variable, displaying a rich range of semantic and syntactic behavior. Verb classifications help NLP systems to deal with this complexity by organizing verbs into groups that share core semantic and syntactic properties. VerbNet (Kipper et al., 2008) is one such lexicon, which identifies semantic roles and syntactic patterns characteristic of the verbs in each class and makes explicit the connections between the syntactic patterns and the underlying semantic relations that can be inferred for all members of the class. Each syntactic frame in a class has a corresponding semantic representation that details the semantic relations between event participants across the course of the event. In the following sections, each component of VerbNet is identified and explained. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource VerbNet is a lexicon of approximately 5800 English verbs, and groups verbs according to shared syntactic behaviors, thereby revealing generalizations of verb behavior. -

A Comparison of the Use of Modal Verbs in Research Articles by Professionals and Non-Native Speaking Graduate Students Jenny Marie Hykes Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 A comparison of the use of modal verbs in research articles by professionals and non-native speaking graduate students Jenny Marie Hykes Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the First and Second Language Acquisition Commons Recommended Citation Hykes, Jenny Marie, "A comparison of the use of modal verbs in research articles by professionals and non-native speaking graduate students" (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7929. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7929 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A comparison of the use of modal verbs in research articles by professionals and non-native speaking graduate students by Jenny Marie Hykes A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Teaching English as a Second Language/Applied Linguistics) Major Professor: Susan Conrad Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2000 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Jenny Marie Hykes has met the thesis requirement of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT vi CHAPTER 1. -

The Modal Verb Should and the Variety of Its Functions

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature The modal verb should and the variety of its functions Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Author: Ing. Helena Budínová Supervisor: Mgr. Radek Vogel, Ph.D. Abstrakt Název: Modální sloveso should a všechny podoby jeho použití Shrnutí: Hlavním cílem této bakalářské práce je kompletní analýza informací o modálním slovese shall a should v daném vzorku anglických gramatik za účelem vytvořit ucelený soubor informací a současně identifikovat rozdílné informace uváděné k této problematice. Práce je členěna do kapitol od teoretického úvodu, přes jednotlivé problematiky výskytu modálního slovesa shall a should až k závěru shrnující výsledky analýzy a naplnění či vyvrácení hypotéz. Klíčová slova: shall, should, modální sloveso, modalita Abstract Title: The modal verb should and the variety of its functions Summary: The main objective of this thesis is a complete analysis on the modal verb should in a given sample of English grammar books in order to create a comprehensive set of information and simultaneously identify different information presented on this issue. The work is divided into chapters of theoretical introduction, over various issues of occurence of modal verbs shall and should to a conclusion summarizing the results of the analysis and proving or disproving given hypotheses. Key words: shall, should, modal verb, modality 2 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č . 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. -

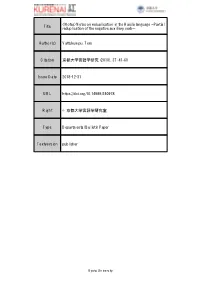

Title <Notes>Notes on Reduplication in the Haisla Language --Partial

<Notes>Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language --Partial Title reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb-- Author(s) Vattukumpu, Tero Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2018), 37: 41-60 Issue Date 2018-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/240978 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 37 (2018), 41 –60 Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language Ü Partial reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb Ü Tero Vattukumpu Abstract: In this paper I will point out that, according to my data, a plural form of the negative auxiliary verb formed by means of partial reduplication exists in the Haisla language in contrary to a description on the topic in a previous study. The plural number of the subject can, and in many cases must, be indicated by using a plural form of at least one of the components of the predicate, i.e. either an auxiliary verb (if there is one), the semantic head of the predicate or both. Therefore, I have examined which combinations of the singular and plural forms of the negative auxiliary verb and different semantic heads of the predicate are judged to be acceptable by native speakers of Haisla. My data suggests that – at least at this point – it seems to be impossible to make convincing generalizations about any patterns according to which the acceptability of different combinations could be determined *. Keywords: Haisla, partial reduplication, negative auxiliary verb, plural, root extension 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce some preliminary notes about reduplication in the Haisla language from a morphosyntactic point of view as a first step towards a better understanding and a more comprehensive analysis of all the possible patterns of reduplication in the language. -

Verb Phrase, Or VP

VP Study Guide In the Logic Study Guide, we ended with a logical tree diagram for WANT (BILL, LEAVE (MARY)), in both unlabelled: WANT BILL LEAVE MARY and labelled versions: P WANT BILL P LEAVE MARY We remarked that one could label the Predicate and Argument nodes as well, and that it was common to use S instead of P to label propositions in such logical tree structures in linguistics. It is also com- mon, in practice, to use V to label Predicates, and N (or NP, standing for Noun Phrase) to label Ar- guments. This would produce the following diagram: S V NP NP Subject Formation WANT BILL S V NP LEAVE MARY Note that, while these two predicates are in fact verbs, and the arguments are nouns, that’s not always the case, and one may use V loosely to label any Predicate node, whatever its syntactic class might be. This kind of structural description, intermediate between logic and surface syntax, is called a deep structure; we say this diagram represents the deep structure of Bill wants Mary to leave. Roughly speaking, deep structures are intended to represent the meaning of the sentence, stripped to its essentials. The deep structures are then related to the actual sentence by a series of relational rules. For instance, one such rule is that in English, there must be a subject NP, and it precedes the verb, instead of coming after it, as here. So we relate this structure with the following one by a rule of Subject Formation, which applies to every deep structure towards the end of the derivation (the series of rule applications; a number of other rules would have already applied earlier, producing the other differences). -

Animacy in Sentence Processing Across Languages: an Information-Theoretic Prospective

ANIMACY IN SENTENCE PROCESSING ACROSS LANGUAGES: AN INFORMATION-THEORETIC PROSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zhong Chen August 2014 c 2014 Zhong Chen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ANIMACY IN SENTENCE PROCESSING ACROSS LANGUAGES: AN INFORMATION-THEORETIC PROSPECTIVE Zhong Chen, Ph.D. Cornell University August 2014 This dissertation is concerned with different sources of information that affect human sentence comprehension. It focuses on the way that syntactic rules in- teract with non-syntactic cues in real-time processing. It develops the idea first introduced in the Competition Model of MacWhinney in the late 1980s such that the weight of a linguistic cue varies among languages. The dissertation addresses this problem from an information-theoretic prospective. The proposed Entropy Reduction metric (Hale, 2003) combines corpus-retrieved attestation frequencies with linguistically-motivated gram- mars. It derives a processing asymmetry called the Subject Advantage that has been observed across languages (Keenan & Comrie, 1977). The modeling re- sults are consistent with the intuitive structural expectation idea, namely that subject relative clauses, as a frequent structure, are easier to comprehend. How- ever, the present research takes this proposal one step further by illustrating how the comprehension difficulty profile reflects uncertainty over different ini- tial substrings. It highlights particular disambiguation