Verb Phrase, Or VP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: the Principles of Language Structure

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: The Principles of Language Structure Ben Newman March 1, 2018 1 What are we studying in this course? This course is about syntax, which is the subfield of linguistics that deals with how words and phrases can be combined to form correct larger forms (usually referred to as sentences). We’re not particularly interested in the structure of words (morphemes), sounds (phonetics), or writing systems, but instead on the rules underlying how words and phrases can be combined across different languages. These rules are what make up the formal grammar of a language. Formal grammar is similar to what you learn in middle and high school English classes, but is a lot more, well, formal. Instead of classifying words based on meaning or what they “do" in a sentence, formal grammars depend a lot more on where words are in the sentence. For example, in English class you might say an adjective is “a word that modifies a noun”, such as red in the phrase the red ball. A more formal definition of an adjective might be “a word that precedes a noun" or “the first word in an adjective phrase" where the adjective phrase is red ball. Describing a formal grammar involves writing down a lot of rules for a language. 2 I-Language and E-Language Before we get into the nitty-gritty grammar stuff, I want to take a look at two ways language has traditionally been described by linguists. One of these descriptions centers around the rules that a person has in his/her mind for constructing sentences. -

Verbals and Verbal Phrases Verbals Are Formed from Verbs but Are Used As Nouns, Adjectives, and Adverbs

Chapter Menu Verbals and Verbal Phrases Verbals are formed from verbs but are used as nouns, adjectives, and adverbs. The three kinds of verbals are the participle, the gerund, and the infinitive. A verbal phrase consists of a verbal and its modifiers and complements. The three kinds of verbal phrases are the participial phrase, the gerund phrase, and the infinitive phrase. The Participle GRAMMAR 16e. A participle is a verb form that can be used as an adjective. Present participles end in –ing. EXAMPLES Esperanza sees the singing canary near the window. [Singing, a form of the verb sing, modifies the noun canary.] Waving, the campers boarded the bus. [Waving, a form of the verb wave, modifies the noun campers.] We could hear it moving in the underbrush. [Moving, a form of the verb move, modifies the pronoun it.] Most past participles end in –d or –ed. Others are irregularly formed. EXAMPLES The baked chicken with yellow rice tasted delicious. [Baked, Reference Note a form of the verb bake, modifies the noun chicken.] For more information on the forms of participles, Confused and frightened, they fled into the jungle. see page 644. For a discus- [Confused, a form of the verb confuse, and frightened, a sion of irregular verbs, form of the verb frighten, modify the pronoun they.] see page 646. In your own words, define each term given below. [Given, a form of the verb give, modifies the noun term.] The perfect tense of a participle is formed with having or with having been. EXAMPLES Having worked all day, Abe was ready for a rest. -

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram. -

PARTS of SPEECH ADJECTIVE: Describes a Noun Or Pronoun; Tells

PARTS OF SPEECH ADJECTIVE: Describes a noun or pronoun; tells which one, what kind or how many. ADVERB: Describes verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs; tells how, why, when, where, to what extent. CONJUNCTION: A word that joins two or more structures; may be coordinating, subordinating, or correlative. INTERJECTION: A word, usually at the beginning of a sentence, which is used to show emotion: one expressing strong emotion is followed by an exclamation point (!); mild emotion followed by a comma (,). NOUN: Name of a person, place, or thing (tells who or what); may be concrete or abstract; common or proper, singular or plural. PREPOSITION: A word that connects a noun or noun phrase (the object) to another word, phrase, or clause and conveys a relation between the elements. PRONOUN: Takes the place of a person, place, or thing: can function any way a noun can function; may be nominative, objective, or possessive; may be singular or plural; may be personal (therefore, first, second or third person), demonstrative, intensive, interrogative, reflexive, relative, or indefinite. VERB: Word that represents an action or a state of being; may be action, linking, or helping; may be past, present, or future tense; may be singular or plural; may have active or passive voice; may be indicative, imperative, or subjunctive mood. FUNCTIONS OF WORDS WITHIN A SENTENCE: CLAUSE: A group of words that contains a subject and complete predicate: may be independent (able to stand alone as a simple sentence) or dependent (unable to stand alone, not expressing a complete thought, acting as either a noun, adjective, or adverb). -

Modals and Auxiliaries 12

Verbs: Modals and Auxiliaries 12 An auxiliary is a helping verb. It is used with a main verb to form a verb phrase. For example, • She was calling her friend. Here the word calling is the main verb and the word was is an auxiliary verb. The words be , have , do , can , could , may , might , shall , should , must , will , would , used , need , dare , ought are called auxiliaries . The verbs be, have and do are often referred to as primary auxiliaries. They have a grammatical function in a sentence. The rest in the above list are called modal auxiliaries, which are also known as modals. They express attitude like permission, possibility, etc. Note the forms of the primary auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs Present tense Past tense be am, is, are was, were do do, does did have has, have had The table below illustrates the application of these primary verbs. Primary auxiliary Function Example used in the formation of She is sewing a dress. continuous tenses I am leaving tomorrow. be in sentences where the The missing child was action is more important found. than the subject 67 EBC-6_Ch19.indd 67 8/12/10 11:47:38 PM when followed by an We are to leave next infinitive, it is used to week. indicate a plan or an arrangement denotes command You are to see the Principal right now. used to form the perfect The carpenter has tenses worked well. have used with the infinitive I had to work that day. to indicate some kind of obligation used to form the He doesn’t work at all. -

Minimum of English Grammar

Parameters Morphological inflection carries with it a portmanteau of parameters, each individually shaping the very defining aspects of language typology. For instance, English is roughly considered a ‘weak inflectional language’ given its quite sparse inflectional paradigms (such as verb conjugation, agreement, etc.) Tracing languages throughout history, it is also worth noting that morphological systems tend to become less complex over time. For instance, if one were to exam (mother) Latin, tracing its morphological system over time leading to the Latin-based (daughter) Romance language split (Italian, French, Spanish, etc), one would find that the more recent romance languages involve much less complex morphological systems. The same could be said about Sanskrit (vs. Indian languages), etc. It is fair to say that, at as general rule, languages become less complex in their morphological system as they become more stable (say, in their syntax). Let’s consider two of the more basic morphological parameters below: The Bare Stem and Pro- drop parameters. Bare Stem Parameter. The Bare Stem Parameter is one such parameter that shows up cross-linguistically. It has to do with whether or not a verb stem (in its bare form) can be uttered. For example, English allows bare verb stems to be productive in the language. For instance, bare stems may be used both in finite conjugations (e.g., I/you/we/you/they speak-Ø) (where speak is the bare verb)—with the exception of third person singular/present tense (she speak-s) where a morphological affix{s}is required—as well as in an infinitival capacity (e.g., John can speak-Ø French). -

Constructions and Result: English Phrasal Verbs As Analysed in Construction Grammar

CONSTRUCTIONS AND RESULT: ENGLISH PHRASAL VERBS AS ANALYSED IN CONSTRUCTION GRAMMAR by ANNA L. OLSON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Linguistics, Analytical Stream We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Emma Pavey, PhD; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Sean Allison, Ph.D.; Second Reader ................................................................................ Dr. David Weber, Ph.D.; External Examiner TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY September 2013 © Anna L. Olson i Abstract This thesis explores the difference between separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs, focusing on finding a reason for the non-separable verbs’ lack of compatibility with the word order alternation which is present with the separable phrasal verbs. The analysis is formed from a synthesis of ideas based on the work of Bolinger (1971) and Gorlach (2004). A simplified version of Cognitive Construction Grammar is used to analyse and categorize the phrasal verb constructions. The results indicate that separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs are similar but different constructions with specific syntactic reasons for the incompatibility of the word order alternation with the non-separable verbs. ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... -

Verbnet Guidelines

VerbNet Annotation Guidelines 1. Why Verbs? 2. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource 3. VerbNet Contents a. The Hierarchy b. Semantic Role Labels and Selectional Restrictions c. Syntactic Frames d. Semantic Predicates 4. Annotation Guidelines a. Does the Instance Fit the Class? b. Annotating Verbs Represented in Multiple Classes c. Things that look like verbs but aren’t i. Nouns ii. Adjectives d. Auxiliaries e. Light Verbs f. Figurative Uses of Verbs 1 Why Verbs? Computational verb lexicons are key to supporting NLP systems aimed at semantic interpretation. Verbs express the semantics of an event being described as well as the relational information among participants in that event, and project the syntactic structures that encode that information. Verbs are also highly variable, displaying a rich range of semantic and syntactic behavior. Verb classifications help NLP systems to deal with this complexity by organizing verbs into groups that share core semantic and syntactic properties. VerbNet (Kipper et al., 2008) is one such lexicon, which identifies semantic roles and syntactic patterns characteristic of the verbs in each class and makes explicit the connections between the syntactic patterns and the underlying semantic relations that can be inferred for all members of the class. Each syntactic frame in a class has a corresponding semantic representation that details the semantic relations between event participants across the course of the event. In the following sections, each component of VerbNet is identified and explained. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource VerbNet is a lexicon of approximately 5800 English verbs, and groups verbs according to shared syntactic behaviors, thereby revealing generalizations of verb behavior. -

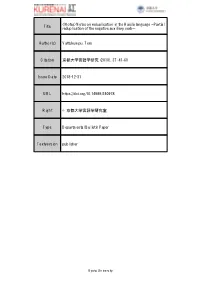

Title <Notes>Notes on Reduplication in the Haisla Language --Partial

<Notes>Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language --Partial Title reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb-- Author(s) Vattukumpu, Tero Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2018), 37: 41-60 Issue Date 2018-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/240978 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 37 (2018), 41 –60 Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language Ü Partial reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb Ü Tero Vattukumpu Abstract: In this paper I will point out that, according to my data, a plural form of the negative auxiliary verb formed by means of partial reduplication exists in the Haisla language in contrary to a description on the topic in a previous study. The plural number of the subject can, and in many cases must, be indicated by using a plural form of at least one of the components of the predicate, i.e. either an auxiliary verb (if there is one), the semantic head of the predicate or both. Therefore, I have examined which combinations of the singular and plural forms of the negative auxiliary verb and different semantic heads of the predicate are judged to be acceptable by native speakers of Haisla. My data suggests that – at least at this point – it seems to be impossible to make convincing generalizations about any patterns according to which the acceptability of different combinations could be determined *. Keywords: Haisla, partial reduplication, negative auxiliary verb, plural, root extension 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce some preliminary notes about reduplication in the Haisla language from a morphosyntactic point of view as a first step towards a better understanding and a more comprehensive analysis of all the possible patterns of reduplication in the language. -

Chapter 2 the Verb Phrase in British English

CHAPTER 2 THE VERB PHRASE IN BRITISH ENGLISH n. The Verb Phrase in British English 2.1 Introductory Remarks The main objective of this chapter is to provide a theoretical background to the verb phrase in BrE. It can be said that tense, aspect, mood and voice are the subsystems that constitute the verb phrase in EngUsh. This chapter discusses the formal and functional features of the verb phrase in BrE. Different classifications related to the verb phrase in BrE are taken into consideration in this chapter. It also presents a brief historical overview of the sub-systems of tense, aspect, mood and voice in English. The present study is based on the framework discussed in Quirk and Greenbaum's 'A University Grammar of English' (1973). 2.2 The Verb Phrase The term 'verb' originally comes from 'were', a proto-Indo- European word which means a 'word'. It comes to English through the Latin word 'Verbum' and the old French word 'Verbe'. Verbs describe actions, events and states and place them in a time frame. They tell us whether actions or events have been completed or are ongoing. They 53 point out whether a state is current or resultative and perform a number of other functions. Therefore, a verb is considered to be the 'heart' of the sentence. Jennings (1992) brings out the importance of the verb by asserting that, 'A verb is a power in all speech' (p. 27). According to Palmer (1965), a verb or a verb phrase is so central to the structure of the sentence that 'no syntactic analysis can proceed without a careful consideration of it' (p. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 166 4th PRASASTI International Conference on Recent Linguistics Research (PRASASTI 2018) The variation of English Verb Phrases in English Cookbook Kadek Ayu Ekasani Ida Bagus Putra Yadnya Sekolah Tinggi Pariwisata Bali Internasional English Department, Denpasar-Bali Faculty of Arts, Udayana University, [email protected] Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia I Ketut Artawa Ni Luh Ketut Mas Indrawati Universitas Udayana Udayana University Denpasar-Bali Denpasar-Bali [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— This writing is entitled “The variation of English such as recipe is very common and verb phrases are more Verb Phrases in English Cookbook”. The discussion is focused on likely to dominate their use in the way they are made. the variation of English verb phrases in Cookbook. The variation of verb phrases here is some complements that follow a verb. The The sentence structure of the cookbook text tends to use data used in this study is taken from English cookbook entitled the verb phrase in initiating instructions for processing dishes. “The Essential Book of Sauces & Dressings” written by Murdoch While the construction of phrases as one part in the field of Books and published by Periplus, Singapore. The main theory is syntax has a fairly complex analysis both in the structure of adopted from the book “The linguistic structure of Modern the phrase itself, as well as its attachment in the predicate English” by Brinton (2010) about the theory of verb phrases. The structure. As it is known that the field of syntax is a mastery methods that are used to collect data are documentation and over a language that includes the ability to build phrases, observation. -

4 the Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion

Introduction to Configurational Syntax Chapter 4 : Chapter 4. 4 The Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion 4.1 Introduction In this chapter the sentence and the verb (predicate) phrase whose head is an auxiliary verb are formally introduced. These two categories do not appear to follow the universal expansion of XP proposed in Chapter 2. In the Principles and Parameters framework of syntax the structure of the sentence can be shown to fol- low the universal expansion of XP. However, the analysis of the sentence given the category CP1 is considered too complex to be covered here. The analyses given here follow the earlier standard views on the structure of the sentence. 4.2 The Sentence At first glance, note that the sentence contains a NP and a VP: (297)a. The moon orbits around the earth. b. [NP the moon ] [VP orbits around the earth ]. We can state the expansion of S (sentence) as: (298) The Expansion of S [1] S ˘ NP VP. The structure for (297 is: (299) [S [NP The moon ] [VP orbits around the earth]] Up to this point we have claimed that all constituents contain a head and a complement. If this is the case then what is the head of S? In advanced work it can be shown to be either tense in some points of view, or the verb in other points of view. In some sense both points of view or correct; however, it is too complex a matter to attempt to explain this here. We will adopt the above expansion, which is traditional and found in most texts, and note that the verb is the unexplained head of the sentence.