UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moroccan Arabic Borrowed Circumfix from Berber: Investigating Morphological Categories in a Language Contact Situation

Lingvistika-2011-01-93 1/5/12 1:32 PM Page 231 Georgia Zellou UDK 811.411.21(64)’06:811.413 University of Colorado Boulder* MOROCCAN ARABIC BORROWED CIRCUMFIX FROM BERBER: INVESTIGATING MORPHOLOGICAL CATEGORIES IN A LANGUAGE CONTACT SITUATION 1. INTRODUCTION Moroccan Arabic (MA, hereafter) has a bound derivational noun circumfix /ta-. .-t/. This circumfix productively attaches to base nouns to derive various types of abstract nouns. This /ta-. .-t/ circumfix is unique because it occurs in no other dialect of Arabic (Abdel-Massih 2009, Bergman 2005, Erwin 1963). There is little question that this mor - pheme has been borrowed from Berber into Moroccan Arabic, as has been noted by some of the earliest analyses of the language (c.f. Guay 1918, Colon 1945). This circumfix is highly productive on native MA noun stems but not productive on borrowed Berber stems (which are rare in MA). This pattern of productivity is taken to be evidence in support of direct borrowing of morphology (c.f. Steinkruger and Seifart 2009) and against a theory where borrowed morphology enters a language as part of unanalyzed complex forms which later spread to native stems (c.f. Thomason and Kaufman 1988; Thomason 2001). Furthermore, it challenges the principle of a “borrowability hierarchy” (c.f. Haugen 1950) where lexical morphemes are borrowed before grammatical morphemes. Additionally, the prefixal portion of the MA circumfix, ta- , is a complex (presumably unanalyzed) form from the Berber /t-/ feminine + /a-/ absolute state. Moreover, the morpheme in MA has been bor - rowed as a derivational morpheme while the primary functions of the donor mor - phemes in Berber are inflectional. -

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

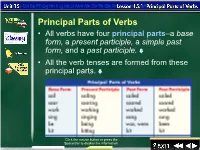

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

Types and Functions of Reduplication in Palembang

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS 12.1 (2019): 113-142 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52447 University of Hawaiʼi Press TYPES AND FUNCTIONS OF REDUPLICATION IN PALEMBANG Mardheya Alsamadani & Samar Taibah Wayne State University [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we study the morphosemantic aspects of reduplication in Palembang (also known as Musi). In Palembang, both content and function words undergo reduplication, generating a wide variety of semantic functions, such as pluralization, iteration, distribution, and nominalization. Productive reduplication includes full reduplication and reduplication plus affixation, while fossilized reduplication includes partial reduplication and rhyming reduplication. We employed the Distributed Morphology theory (DM) (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994) to account for these different patterns of reduplication. Moreover, we compared the functions of Palembang reduplication to those of Malay and Indonesian reduplication. Some instances of function word reduplication in Palembang were not found in these languages, such as reduplication of question words and reduplication of negators. In addition, Palembang partial reduplication is fossilized, with only a few examples collected. In contrast, Malay partial reduplication is productive and utilized to create new words, especially words borrowed from English (Ahmad 2005). Keywords: Reduplication, affixation, Palembang/Musi, morphosemantics ISO 639-3 codes: mui 1 Introduction This paper has three purposes. The first is to document the reduplication patterns found in Palembang based on the data collected from three Palembang native speakers. Second, we aim to illustrate some shared features of Palembang reduplication with those found in other Malayic languages such as Indonesian and Malay. The third purpose is to provide a formal analysis of Palembang reduplication based on the Distributed Morphology Theory. -

Periphrastic Causative Constructions in Mehweb Daria Barylnikova National Research University Higher School of Economics

Chapter 6 Periphrastic causative constructions in Mehweb Daria Barylnikova National Research University Higher School of Economics In Mehweb, periphrastic causatives are formed by a combination of the infinitive of the lexical verb with another verb, originally a caused motion verb. Various tests that Mehweb periphrastic causatives do not qualify as fully grammaticalized. But the constructions are not compositional expressions, either. While a clause usually contains either a morphological or a periphrastic causative marker, there are instances where, in a periphrastic causative construction, the lexical verb itself may carry the causative affix, resulting in only one causative meaning. Keywords: causative, periphrastic causative, double causative, Mehweb, Dargwa, East Caucasian. 1 Introduction The causative construction denotes a complex situation consisting of twocom- ponent events: (1) the event that causes another event to happen; and (2) the result of this causation (Comrie 1989: 165–166; Nedjalkov & Silnitsky 1973; Ku- likov 2001). Here, the first event refers to the action of the causer and the second explicates the effect of the causation on the causee. Causativization is a valency-increasing derivation which is applied to the structure of the clause. In the resulting construction, the causer is the subject and the causee shifts to a non-subject position. The set of semantic roles does not remain the same. Minimally, a new agent is added. With a new argument added, we have to redistribute the grammatical relations taking into account how these participants semantically relate to each other. The general scheme of the causative derivation always implies a participant that is treated as a causer (someone or something that spreads their control over the situation and “pulls Daria Barylnikova. -

Deponent Verbs in Georgian Kevin Tuite (Université De Montréal)

Deponent verbs in Georgian Kevin Tuite (Université de Montréal) 0. Introduction. In the summer of 2000, while on a research trip to Georgia, I came across the following cartoon in a Tbilisi newspaper. Here is the text with a translation: Waiter: supši rat’om ipurtxebit? (Why do you keep spitting in the soup?) Customer: vsinǰav, cxelia tu ara. (I’m testing if it’s hot or not.) Waiter: ??? Customer: čemi coli q’oveltvis egre amoc’mebs utos. (My wife always checks the iron like this.) Leaving aside the political incorrectness — on several levels — of the content of the cartoon, let us make use of it as a source of linguistic data. The verb in the first line, i-purtx-eb-i-t “you [pl/polite] spit”, is formally in the passive voice; its 3rd-person subject form would be i- purtx-eb-a. Its morphology contrasts with that of the transitive a-purtx- eb-s in exactly the same way as, say, the passive (k’ari) i-ɣ-eb-a “(the door) is opened” is opposed to the active (k’ars) a-ɣ-eb-s “s/he opens (the door)”. If the meaning of a-purtx-eb-s is “s/he spits”, one would expect the first line of the above dialogue to mean something along the lines of “Why are you being spit into the soup?”, which is manifestly not the case. The Explanatory Dictionary of the Georgian Language (KEGL) glosses ipurtxeba “spits continually, sprays spit all the time (from the mouth)” (erttavad apurtxebs, c’ara-mara purtxs isvris (p’iridan)); according to Tschenkéli’s dictionary, it means “(dauernd) spucken”. -

The Syntax of Simple and Compound Tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko*

Proc Ling Soc Amer Volume 1, Article 18:1-15 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v1i0.3716 The Syntax of simple and compound tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko* Abstract. It is a widely accepted generalization that verbal periphrasis is triggered by in- creased inflectional meaning and a paucity of verbal elements to support its realization. This work examines the limitations on synthetic verbal forms in Ndebele and argues that periphrasis in this language arises via a last-resort grammatical mechanism. The proposed trigger of auxiliary insertion is c-selection – a relation between inflectional categories and verbs. Keywords. verbal periphrasis; default auxiliary; c-selection; Ndebele; Bantu 1. Introduction. This paper focuses on the mechanics of default periphrasis – a phenomenon where a default verb (an auxiliary) appears in a complex inflectional context. I provide an anal- ysis of two types of compound tenses in Ndebele:1 Perfect and Prospective tenses, arguing that periphrastic expressions in those tenses are triggered by c-selectional features on T heads. The type of verbal periphrasis we find in Ndebele is known as the overflow pattern of auxiliary use (Bjorkman, 2011), and is illustrated in (1),2 where Present Perfect and Simple Future are synthetic (there is no auxiliary), but Future Perfect is periphrastic (1-c). (1) Default periphrasis in Ndebele: a. U- ∅- dl -ile Present Perfect/Recent Past (synthetic) 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You have eaten/you ate recently’. b. U- za- dl -a Simple Future (synthetic) 2sg- FUT- eat -FS ‘You will eat’. c. U- za- be u- ∅- dl -ile Future Perfect (periphrastic) 2sg- FUT- aux 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You will have eaten’. -

“Possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31

Nomen: ____________________________________________________________________________ Classis: ________ Review Notes: “possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31 Principal parts of the verb “possum”: possum, posse, potui, ----- to be able to, can Possum is a compound of the verb sum. It is essentially the prefix pot added to the irregular verb sum. However, the letter t in the prefix pot becomes s in front of all forms of sum beginning with the letter s. Let’s look at the forms of the verb “possum” below and their translations: Present Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1. possum I can, I am able possumus We can, we are able 2. potes You can, you are able potestis Y’all can, are able 3. potest He/she/it can, is able possunt They can, are able Imperfect Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.poteram I could, was able poteramus We could, were able 2.poteras You could, were able poteratis Y’all could, were able 3.poterat He/she/it could, was able poterant They could, were able Future Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.potero I will be able poterimus We will be able 2.poteris You will be able poteritis Y’all will be able 3.poterit He/she/it will be able poterunt They will be able So what about the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect forms of the verb “possum”? These tenses are regular, meaning possum follows the normal rules. Let’s look at them. Start by rewriting your principal parts of the verb: Possum, posse, potui, ------ to be able to, can Just like all other verbs, switch to the 3rd principal part when you want to work in the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect tenses. -

Infixing Reduplication in Pima and Its Theoretical Consequences

Infixing Reduplication in Pima and its Theoretical Consequences 1 Introduction Pima reduplication offers an interesting analytic puzzle, the solution of which bears on a number of important issues in the theory of reduplication. In this paper I will present the Pima data, provide an analysis within the framework of Optimality Theory (OT; Prince and Smolensky 1993), and address the theoretical implications of this analysis. I will argue that a particular set of reduplicative patterns that previous scholars have analyzed as prefixing reduplication plus syncope in the base can be analyzed simply as infixing reduplication. Moreover I will show that these two analyses have very different theoretical ramifications. At stake are the flexibility with which a grammar is allowed to pick out which segments get copied in reduplication and the nature of the distinction between the base and the reduplicant. 1.1 Overview Reduplication in Pima occurs at the left edge of the word and is used to mark plural forms of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, verbs and even some determiners.1 Pima Reduplication is particularly interesting because the amount of material that appears twice in the pluralized forms varies between a single consonant and the initial CV sequence. I will refer to these two patterns of reduplication C-Copying and CV-Copying respectively. (1) a. C-Copying: ma.vit ‘lion’ mam.vit ‘lions’ b. CV-Copying: ho.dai ‘rock’ ho.ho.dai ‘rocks’ I use the term ‘copying’ here simply to reference the material that appears twice in reduplicated forms and not to indicate an assumption about which substring of the surface form is the reduplicant. -

Aorist and Pseudo-Aorist for Svan Atelic Verbs — K. Tuite 0. Introduction. the Kartvelian Or South Caucasian Family Comprises

Aorist and pseudo-aorist for Svan atelic verbs — K. Tuite 0. Introduction. The Kartvelian or South Caucasian family comprises three languages: Georgian, which has been attested in documents going back to the 5th century, Zan (or Laz-Mingrelian) and Svan. In the case of Zan and Svan, there is almost no documentation going back beyond the mid-19th century. There is a concensus among experts that Svan is the outlying member of the family, whose family tree would be as in this diagram: COMMON KARTVELIAN COMMON GEORGIAN-ZAN PREHISTORIC SVAN GEORGIAN ZAN MINGRELIAN LAZ Upper Bal Lower Bal Lashx Lent’ex (Upper Svan dialects) (Lower Svan dialects) In this paper I will look at one segment of the formal system in Svan — in particular, in the more conservative Upper Svan dialects — for coding aspect. In this introductory section I will go over the system of what Kartvelologists term “screeves” (sets of verb forms differing only in person and number), and then the classification of verbs by lexical aspect with which the morphological facts will be compared. 0.1. Screeves and series. In the morphology of verbs in each of the Kartvelian languages, one of the fundamental distinctions is between verb forms derived from the SERIES I OR “PRESENT-SERIES” stem, and forms derived from the SERIES II OR “AORIST-SERIES” stem. We will not go into all of the formal differences between these two stems for the various groups of verbs in each language, save to note that for most verbs the Series I stem contains a suffix (the “series marker” or “present/future stem formant”) which does not appear in Series II forms. -

Causes of War Prospects for Peace

Georgian Orthodox Church Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung CAUSES OF WAR PROS P E C TS FOR PEA C E Tbilisi, 2009 1 On December 2-3, 2008 the Holy Synod of the Georgian Orthodox Church and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung held a scientific conference on the theme: Causes of War - Prospects for Peace. The main purpose of the conference was to show the essence of the existing conflicts in Georgia and to prepare objective scientific and information basis. This book is a collection of conference reports and discussion materials that on the request of the editorial board has been presented in article format. Publishers: Metropolitan Ananya Japaridze Katia Christina Plate Bidzina Lebanidze Nato Asatiani Editorial board: Archimandrite Adam (Akhaladze), Tamaz Beradze, Rozeta Gujejiani, Roland Topchishvili, Mariam Lordkipanidze, Lela Margiani, Tariel Putkaradze, Bezhan Khorava Reviewers: Zurab Tvalchrelidze Revaz Sherozia Giorgi Cheishvili Otar Janelidze Editorial board wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Irina Bibileishvili, Merab Gvazava, Nia Gogokhia, Ekaterine Dadiani, Zviad Kvilitaia, Giorgi Cheishvili, Kakhaber Tsulaia. ISBN 2345632456 Printed by CGS ltd 2 Preface by His Holiness and Beatitude Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia ILIA II; Opening Words to the Conference 5 Preface by Katja Christina Plate, Head of the Regional Office for Political Dialogue in the South Caucasus of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung; Opening Words to the Conference 8 Abkhazia: Historical-Political and Ethnic Processes Tamaz Beradze, Konstantine Topuria, Bezhan Khorava - A