Michael Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

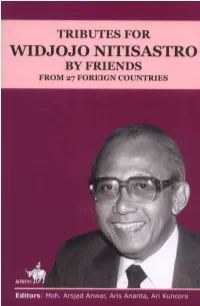

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

New Trends in Mao Literature from China

Kölner China-Studien Online Arbeitspapiere zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas Cologne China Studies Online Working Papers on Chinese Politics, Economy and Society No. 1 / 1995 Thomas Scharping The Man, the Myth, the Message: New Trends in Mao Literature From China Zusammenfassung: Dies ist die erweiterte Fassung eines früher publizierten englischen Aufsatzes. Er untersucht 43 Werke der neueren chinesischen Mao-Literatur aus den frühen 1990er Jahren, die in ihnen enthaltenen Aussagen zur Parteigeschichte und zum Selbstverständnis der heutigen Führung. Neben zahlreichen neuen Informationen über die chinesische Innen- und Außenpolitik, darunter besonders die Kampagnen der Mao-Zeit wie Großer Sprung und Kulturrevolution, vermitteln die Werke wichtige Einblicke in die politische Kultur Chinas. Trotz eindeutigen Versuchen zur Durchsetzung einer einheitlichen nationalen Identität und Geschichtsschreibung bezeugen sie auch die Existenz eines unabhängigen, kritischen Denkens in China. Schlagworte: Mao Zedong, Parteigeschichte, Ideologie, Propaganda, Historiographie, politische Kultur, Großer Sprung, Kulturrevolution Autor: Thomas Scharping ([email protected]) ist Professor für Moderne China-Studien, Lehrstuhl für Neuere Geschichte / Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas, an der Universität Köln. Abstract: This is the enlarged version of an English article published before. It analyzes 43 works of the new Chinese Mao literature from the early 1990s, their revelations of Party history and their clues for the self-image of the present leadership. Besides revealing a wealth of new information on Chinese domestic and foreign policy, in particular on the campaigns of the Mao era like the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution, the works convey important insights into China’s political culture. In spite of the overt attempts at forging a unified national identity and historiography, they also document the existence of independent, critical thought in China. -

Failure of Bilateral Diplomacy on Irian Barat (Papua) Dispute (1950-1954)

FAILURE OF BILATERAL DIPLOMACY ON IRIAN BARAT (PAPUA) DISPUTE (1950-1954) Siswanto Center for Political Studies, The Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jakarta E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Fundamentally, Irian Barat (Papua) dispute between The Netherlands –Indonesia was a territorial conflict or an overlapping claim. The Netherlands as the former colonialist did not want to leave Irian Barat (Papua) or remained still in the region, meanwhile Indonesia as the former colony denied the Netherlands status quo policy in Irian Barat (Papua). Potential dispute of the Irian Barat (Papua) was begun in the Round Table Conference (RTC) 1949. There was a point of agreement in RTC which regulates status quo on Irian Barat (Papua) and it was approved by Head of Indonesia Delegation, Mohammad Hatta and Van Maarseven, Head of the Netherlands Delegation. As a mandate of the RTC in 1950s there was a diplomacy on Irian Barat (Papua) in Jakarta and Den Haag. Upon the diplomacy, there were two negotiations held by diplomats of both countries, yet it never reached a result. As a consequence, in 1954 Indonesia Government decided to stop the negotiation and searched for other ways as a solution for the dispute. At the present time, Jakarta-Papua relationship is relatively better and it is based on a special autonomy, which gives great authority to the Local Government of Papua. Keywords: the Netherlands, Indonesia, status quo, Irian Barat (Papua), diplomacy Abstrak Pada dasarnya perselisihan Irian Barat (Papua) antara Belanda –Indonesia adalah konflik teritorial atau tumpang tindih klaim. Belanda sebagai mantan penjajah tidak ingin meninggalkan Irian Barat (Papua) atau masih ingin menduduki kawasan itu, di sisi lain Indonesia sebagai bekas bangsa terjajah menolak kebijakan status quo Belanda di Irian Barat (Papua). -

INDONESIA's FOREIGN POLICY and BANTAN NUGROHO Dalhousie

INDONESIA'S FOREIGN POLICY AND ASEAN BANTAN NUGROHO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia September, 1996 O Copyright by Bantan Nugroho, 1996 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibbgraphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Lïbraiy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papa or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substautid extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. DEDICATION To my beloved Parents, my dear fie, Amiza, and my Son, Panji Bharata, who came into this world in the winter of '96. They have been my source of strength ail through the year of my studies. May aii this intellectual experience have meaning for hem in the friture. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents v List of Illustrations vi Abstract vii List of Abbreviations viii Acknowledgments xi Chapter One : Introduction Chapter Two : indonesian Foreign Policy A. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini

Daftar Isi EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 39 SELINGAN 78 Profil Taman Makam Pahlawan Agun Gunandjar 10 BERITA UTAMA Pengantar Redaksi ...................................................... 04 Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini ................................................................................... 06 Persoalan pekerja migran sesungguhnya adalah persoalan Kolom ................................................................................... 08 serius. Banyaknya persoalan yang dihadapi pekerja migran Indonesia menunjukkan ketidakseriusan dan ketidakmampuan Bicara Buku ...................................................................... 38 negara memberikan perlindungan kepada pekerja migran. Aspirasi Masyarakat ..................................................... 47 Debat Majelis ............................................................... 48 Varia MPR ......................................................................... 71 Wawancara ..................................................... 72 Figur .................................................................................... 74 Ragam ................................................................................ 76 Catatan Tepi .................................................................... 82 18 Nasional Press Gathering Wartawan Parlemen: Kita Perlu Demokrasi Ala Indonesia COVER 54 Sosialisasi Zulkifli Hasan : Berpesan Agar Tetap Menjaga Persatuan Edisi No.11/TH.XII/November 2018 Kreatif: Jonni Yasrul - Foto: Istimewa EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 3 -

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: the Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: The Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015 Taufiqurrahman, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia Budi Endarto, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia The Asian Conference on Business and Public Policy 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The Head of the State Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Summit of Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2007 on Cebu, Manila agreed to accelerate the implementation of ASEAN Economy Community (AEC), which was originally 2020 to 2015. This means that within the next seven months, the people of Indonesia and ASEAN member countries more integrated into one large house named AEC. This in turn will further encourage increased volume of international trade, both by the domestic consumers to foreign businesses, among foreign consumers by domestic businesses, as well as between foreign entrepreneurs with domestic businesses. As a result, the potential for legal disputes between the parties in international trade transactions can not be avoided. Therefore, the existence of the contract law of international commercial law in order to provide maximum protection for the parties to a transaction are indispensable. The existence of this legal regime will provide great benefit to all parties to a transaction to minimize disputes. This study aims to assess the significance of the governing of International Commercial Contract Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 and also to find legal principles underlying governing the International Commercial Contracts Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 so as to provide a valuable contribution to the development of Indonesian national law. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

INDO 50 0 1106971426 29 60.Pdf (1.608Mb)

A m e r ic a n " L o w P o s t u r e " P o l ic y t o w a r d In d o n e s ia in t h e M o n t h s L e a d in g u p t o t h e 1965 "C o u p " 1 Frederick Bunnell Introduction This article seeks to contribute to the reconstruction, explanation, and evaluation of the Johnson Administration's response to President Sukarno's radicalization of Indonesia's do mestic politics and foreign policy in the first nine months of 1965 leading up to the abortive "coup" on October 1,1965. The focus throughout is on both the thinking and the politics of what can be termed "the 1965 Indonesia policy group."2 That unofficial group was the informal constellation of US officials both in Indonesia (in the Embassy-based country team)3 and in Washington (in the *This article has enjoyed a long, troubled odyssey. Growing out of intermittent research on American-Indonesian relations dating back to my doctoral dissertation field research in Jakarta in 1963-1965, the substance of the article, including its primary conclusions, was presented in papers at the August 1979 Indonesian Studies Con ference in Berkeley and the March 1980 International Studies Association Conference in Los Angeles. I am in debted to the American Philosophical Society, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, and the Vassar College Faculty Research Committee for grants in 1976-1979 which facilitated the brunt of the archival and interview re search undergirding the article.