INDONESIA's FOREIGN POLICY and BANTAN NUGROHO Dalhousie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspective of the 1945 Constitution As a Democratic Constitution Hotma P

Comparative Study of Post-Marriage Nationality Of Women in Legal Systems of Different Countries http://ijmmu.com [email protected] International Journal of Multicultural ISSN 2364-5369 Volume 7, Issue 1 and Multireligious Understanding February, 2020 Pages: 779-792 A Study on Authoritarian Regime in Indonesia: Perspective of the 1945 Constitution as a Democratic Constitution Hotma P. Sibuea1; Asmak Ul Hosnah2; Clara L. Tobing1 1 Faculty of Law University Bhayangkara Jakarta, Indonesia F2 Faculty of Law University Pakuan, Indonesia http://dx.doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v7i1.1453 Abstract The 1945 Constitution is the foundation of the constitution of Indonesia founded on the ideal of Pancasila that comprehend democratic values. As a democratic constitution, the 1945 Constitution is expected to form a constitutional pattern and a democratic government system. However, the 1945 Constitution has never formed a state structure and a democratic government system since it becomes the foundation of the constitution of the state of Indonesia in the era of the Old Order, the New Order and the reform era. Such conditions bear the question of why the 1945 Constitution as a democratic constitution never brings about the pattern of state administration and democratic government system. The conclusion is, a democratic constitution, the 1945 Constitution has never formed a constitutional structure and democratic government system because of the personal or group interests of the dominant political forces in the Old Order, the New Order and the reformation era has made the constitutional style and the system of democratic governance that cannot be built in accordance with the principles of democratic law reflected in the 1945 Constitution and derived from the ideals of the Indonesian law of Pancasila. -

Management of Communism Issues in the Soekarno Era (1959-1966)

57-67REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION ISSN: 2146-0353 ● © RIGEO ● 11(5), SPRING, 2021 www.rigeo.org Research Article Management of Communism Issues in The Soekarno Era (1959-1966) Abie Besman1 Dian Wardiana Sjuchro2 Faculty of Communication Science, Universitas Faculty of Communication Science, Universitas Padjadjaran Padjadjaran [email protected] Abstract The focus of this research is on the handling of the problem of communism in the Nasakom ideology through the policies and patterns of political communication of President Soekarno's government. The Nasakom ideology was used by the Soekarno government since the Presidential Decree in 1959. Soekarno's middle way solution to stop the chaos of the liberal democracy period opened up new conflicts and feuds between the PKI and the Indonesian National Army. The compromise management style is used to reduce conflicts between interests. The method used in this research is the historical method. The results showed that the approach adopted by President Soekarno failed. Soekarno tried to unite all the ideologies that developed at that time, but did not take into account the political competition between factions. This conflict even culminated in the events of September 30 and the emergence of a new order. This research is part of a broader study to examine the management of the issue of communism in each political regime in Indonesia. Keywords Nasakom; Soekarno; Issue Management; Communism; Literature Study To cite this article: Besman, A.; and Sj uchro, D, W. (2021) Management of Communism Issues in The Soekarno Era (1959-1966). Review of International Geographical Education (RIGEO), 11(5), 48-56. -

Contemporary History of Indonesia Between Historical Truth and Group Purpose

Review of European Studies; Vol. 7, No. 12; 2015 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Contemporary History of Indonesia between Historical Truth and Group Purpose Anzar Abdullah1 1 Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia Correspondence: Anzar Abdullah, Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 28, 2015 Accepted: October 13, 2015 Online Published: November 24, 2015 doi:10.5539/res.v7n12p179 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v7n12p179 Abstract Contemporary history is the very latest history at which the historic event traces are close and still encountered by us at the present day. As a just away event which seems still exists, it becomes controversial about when the historical event is actually called contemporary. Characteristic of contemporary history genre is complexity of an event and its interpretation. For cases in Indonesia, contemporary history usually begins from 1945. It is so because not only all documents, files and other primary sources have not been uncovered and learned by public yet where historical reconstruction can be made in a whole, but also a fact that some historical figures and persons are still alive. This last point summons protracted historical debate when there are some collective or personal memories and political consideration and present power. The historical facts are often provided to please one side, while disagreeable fact is often hidden from other side. -

Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini

Daftar Isi EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 39 SELINGAN 78 Profil Taman Makam Pahlawan Agun Gunandjar 10 BERITA UTAMA Pengantar Redaksi ...................................................... 04 Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini ................................................................................... 06 Persoalan pekerja migran sesungguhnya adalah persoalan Kolom ................................................................................... 08 serius. Banyaknya persoalan yang dihadapi pekerja migran Indonesia menunjukkan ketidakseriusan dan ketidakmampuan Bicara Buku ...................................................................... 38 negara memberikan perlindungan kepada pekerja migran. Aspirasi Masyarakat ..................................................... 47 Debat Majelis ............................................................... 48 Varia MPR ......................................................................... 71 Wawancara ..................................................... 72 Figur .................................................................................... 74 Ragam ................................................................................ 76 Catatan Tepi .................................................................... 82 18 Nasional Press Gathering Wartawan Parlemen: Kita Perlu Demokrasi Ala Indonesia COVER 54 Sosialisasi Zulkifli Hasan : Berpesan Agar Tetap Menjaga Persatuan Edisi No.11/TH.XII/November 2018 Kreatif: Jonni Yasrul - Foto: Istimewa EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 3 -

Ganefo Sebagai Wahana Dalam Mewujudkan Konsepsi Politik Luar Negeri Soekarno 1963-1967

AVATARA, e-Journal Pendidikan Sejarah Volume1, No 2, Mei 2013 GANEFO SEBAGAI WAHANA DALAM MEWUJUDKAN KONSEPSI POLITIK LUAR NEGERI SOEKARNO 1963-1967 Bayu Kurniawan Jurusan Pendidikan Sejarah, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial Universitas Negeri Surabaya E-mail: [email protected] Septina Alrianingrum Jurusan Pendidikan Sejarah, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial Universitas Negeri Surabaya Abstrak Ganefo adalah salah satu peristiwa sejarah yang diharapkan mampu menumbuhkan kembali rasa nasionalisme dan kebanggaan para generasi penerus bangsa untuk melanjutkan api semangat yang telah dikobarkan Soekarno. Melalui metode penelitian sejarah yang terdiri dari (1) heuristik, (2) kritik, (3) interpretasi dan (4) historiografi, peneliti menghasilkan sebuah karya mengenai Games Of The New Emerging Forces atau Ganefo antara lain, (1) latar belakang Soekarno menyelenggarakan Ganefo, (2) pelaksanaan Ganefo, (3) dampak pelaksanaan Ganefo bagi Indonesia. Ganefo sukses dilaksanakan pada 10 hingga 22 November 1963. Atlet Indonesia dalam Ganefo juga meraih sukses dengan menempati posisi kedua, dibawah RRT sebagai juara umum. Kesuksesan Ganefo membuat IOC mencabut skorsing yang telah dijatuhkan kepada Indonesia sehingga dapat kembali berpartisipasi dalam Olimpiade Tokyo 1964. Bagi Soekarno Ganefo adalah pijakan awal untuk menggalang kekuatan negara-negara yang tergabung dalam Nefo karena Indonesia berhasil mendapatkan perhatian dunia dan menjadi negara yang patut diperhitungkan eksistensinya. Indonesia dijadikan simbol bagi perlawanan terhadap imperialisme dan membuktikan dalam situasi keterbatasan mampu menyelenggarakan even bertaraf internasional dengan kesungguhan dan tekad untuk melakukan sesuatu yang bagi sebagian orang mustahil dilakukan, sesuai dengan semboyan Ganefo “On Ward! No Retreat!”, Kata Kunci : Soekarno, Ganefo, Politik Luar Negeri Abstract Ganefo is one of the historical events that are expected to foster a sense of nationalism and pride the next generation to continue the spirit of the fire that has been flamed Soekarno. -

BANDDUNG-At-60-NEW-INSIGHT

INTRODUCTION EMERGING MOVEMENTS Darwis Khudori, Bandung Conference and its Constellation — Seema Mehra Parihar, Scripting the Change: Bandung+60 pp. vii-xxv engaging with the Gender Question and Gendered Spaces — pp. 175-193 HISTORY Trikurnianti Kusumanto, More than food alone: Food Security in the South and Global Environmental Change — Darwis Khudori, Bandung Conference: the Fundamental pp. Books — pp. 3-33 194-206 Naoko Shimazu, Women Performing “Diplomacy” at the Bandung Conference of 1955 — pp. 34-49 EMERGING COUNTRIES Beatriz Bissio, Bandung-Non Alignment-BRICS: A Journey of the Bandung Spirit — GLOBAL CHALLENGES pp. 209-215 Two Big Economic Manoranjan Mohanty, Bandung, Panchsheel and Global Tulus T.H. Tambunan and Ida Busnetty, Crises: The Indonesian Experience and Lessons Learned Swaraj — pp. 53-74 for Other Asian-African Developing Countries — pp. Noha Khalaf, Thinking Global: Challenge FOR Palestine — 216-233 pp. 75-97 Sit Tsui, Erebus Wong, Wen Tiejun, Lau Kin Chi, Comparative Study on Seven Emerging Developing INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Countries: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Adams Bodomo, Africa-Asia relations: How Bandung Turkey, Venezuela — pp. 234-257 redefined area and international studies — pp. 101-119 Lazare Ki-zerbo, The International experience South Group EMERGING CONCERNS Network (ISGN): lessons and perspectives post-2015 — Lin Chun, Toward a new moral economy: rethinking land pp. 120-138 reform in China and India — pp. 261-286 István Tarrósy, Bandung in an Interpolar Context: What Lau Kin Chi, Taking Subaltern and Ecological Perspectives on ‘Common Denominators’ Can the New Asian-African Sustainability in China — pp. 287-304 Strategic Partnership Offer? — pp. 139-148 Mérick Freedy Alagbe, In search of international order: From CLOSING REMARK Bandung to Beijing, the contribution of Afro-Asian nations — pp. -

11. the Touchy Historiography Of

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2018-01 Flowers in the Wall: Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia Webster, David University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/106249 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca FLOWERS IN THE WALL Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia by David Webster ISBN 978-1-55238-955-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Back in Asia: the US's TPP Initiative and Its Implications for China

Southeast Asian Journal of Social and Political Issues, Vol. 1, No. 2, March 2012 | 126 Back in Asia: the US’s TPP Initiative and its Implications for China Zhang Zhen-Jiang 张振江 (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China) Abstract Trans-Pacific Partnership develops from the Pacific Three Closer Economic Partnership (P3-CEP) initiated by Chile, Singapore and New Zealand in 2002 and joined by Brunei in 2005. The four countries finally finished their talks and singed the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (P4) on June 3rd, 2005. American President George W. Bush announced that the US would join TPP in late 2008. It was suspended by new American President Barrack Obama for his trade policy review. However, the US government restarted its joining efforts in late 2009 and was quickly joined by several other countries. This paper aims to investigate the origin, nature and development of TPP, analyze America’s motivations, and study its possible impacts upon the East Asian Regionalism in general and upon China in particular. Finally, the author calls for China to take the active policy to join the TPP negotiating process. Keywords: TPP, America’s Trade Policy, East Asian Regionalism, China Introduction On December 14 2009, the Office of the United States Trade Representative formally notified the Congress that Obama Administration is planning to engage with the “Trans-Pacific Partnership” (thereafter “TPP”). American government formally started the first round negotiation with Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Chile, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam in March 15-18, 2010 in Melbourne. Up to now, seven rounds of negotiations have been held (Round 2 in San Francisco in June 11-18 2010, Round 3 in Brunei in October 7-8 2010, Round 4 in Auckland in December 6-8, 2010, Round 5 in Santiago in February 14-18 2011, Round 6 in Singapore in April 2011, and Round 7 in Ho Chi Minh City in June 19-24 2011). -

Bandung Conference and Its Constellation: an Introdu Ction

BANDUNG LEGACY AND GLOBAL FUTURE: New Insights and Emerging Forces, New Delhi, Aakar Book s , 2018, pp. 1 - 20. 1 /20 Bandung Conference and its Constellation: An Introdu ction Darwis Khudori 2015 is the year of the 60 th anniversary of the 1955 Bandung Asian - African Conference. Several events were organised in diverse countries along the year 2014 - 2015 in order to commemorate this turning point of world history. In Euro pe, two of the most prestigious universities in the world organised special seminars open to public for this purpose: The University of Paris 1 Pantheon - Sorbonne, Bandung 60 ans après : quel bilan ? (Bandung 60 Years on: What Assessment?), June 27, 2014, a nd Leiden - based academic institutions, Bandung at 60: Towards a Genealogy of the Global Present , June 18, 2015. In Africa, two events echoing the Bandung Conference are worth mentioning: The World Social Forum, Tunisia, March 25 - 28, 2015, and The Conferenc e Africa - Asia: A New Axis of Knowledge, Accra, Ghana, September 24 - 26, 2015. In Latin America, the Journal America Latina en movimiento published an issue titled 60 años después Vigencia del espíritu de Bandung, mayo 2015. In USA, a panel on Bandung +60: L egacies and Contradictions was organised by the International Studies Association in New Orleans, February 18, 2015. In Asia, China Academy of Arts, Inter - Asia School, and Center for Asia - Pacific/Cultural Studies, Chiao Tung University, Hangzhou, organised a conference on BANDUNG – Third World 60 Years, April 18 - 19, 2015. On the same dates, a conference on Vision of Bandung after 60 years: Facing New Challenges was organised by AAPSO (Afro - Asian People’s Solidarity Organisation) in Kathmandu, Nepal. -

Democracy and Human Security: Analysis on the Trajectory of Indonesia’S Democratization

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 456 Proceedings of the Brawijaya International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences and Technology (BICMST 2020) Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 456 Proceedings of the Brawijaya International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences and Technology (BICMST 2020) Democracy and Human Security: Analysis on the Trajectory of Indonesia’s Democratization Rika Kurniaty Department of International Law Faculty of Law, University of Brawijaya Malang, Indonesia [email protected] The concept of national security has a long Abstract—Democracy institution is believed would history, since the conclusion of the thirty-year naturally lead to greater human security. The end of cessation of war set forth in the Treaties of Westphalia communism in the Soviet Union and other countries has in 1648. National security was defined as an effort been described as the triumph of democracy throughout the world, which quickly led to claims that there is now a aimed at maintaining the integrity of a territory the right to democracy as guide principles in international state and freedom to determine the form of self- law. In Indonesia, attention to the notion of democracy government. However, with global developments and developed very rapidly in the late 1990s. In Indonesia, after 32 years of President Suharto’s authoritarian increasingly complex relations between countries and regime from 1966 to 1998, Indonesia finally began the the variety of threats faced by countries in the world, democratization phase in May 1998. It worth noting that the formulation and practice of security Indonesia has experienced four different periods of implementation tend to be achieved together different government and political systems since its (collective security) becomes an important reference independent, and all those stage of systems claim to be for countries in the world. -

“After Suharto” in Newsweek and “End of an Era” Article in Time Magazine

NEWS IDEOLOGY OF SUHARTO’S FALL EVENT IN “AFTER SUHARTO” IN NEWSWEEK AND “END OF AN ERA” ARTICLE IN TIME MAGAZINE AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MEITA ESTININGSIH Student Number: 044214102 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 NEWS IDEOLOGY OF SUHARTO’S FALL EVENT IN “AFTER SUHARTO” IN NEWSWEEK AND “END OF AN ERA” ARTICLE IN TIME MAGAZINE AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MEITA ESTININGSIH Student Number: 044214102 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 i ii iii A newspaper is a collection of half-injustices Which, bawled by boys from mile to mile, Spreads its curious opinion To a million merciful and sneering men, While families cuddle the joys of the fireside When spurred by tale of dire lone agony. A newspaper is a court Where every one is kindly and unfairly tried By a squalor of honest men. A newspaper is a market Where wisdom sells its freedom And melons are crowned by the crowd. A newspaper is a game Where his error scores the player victory While another's skill wins death. A newspaper is a symbol; It is feckless life's chronicle, A collection of loud tales Concentrating eternal stupidities, That in remote ages lived unhaltered, Roaming through a fenceless world. A poem by Stephen crane iv g{|á à{xá|á |á wxw|vtàxw àÉ Åç uxÄÉäxw ÑtÜxÇàá? ytÅ|Äç tÇw yÜ|xÇwá‹ TÇw àÉ tÄÄ à{x ÑxÉÑÄx ã{É Üxtw à{|á‹ v STATEMENT OF WORK’S ORIGINALITY I honestly declared that this thesis, which I have written, does not contain the work or parts of the work of other people, except those cited in the quotations and the references, as a scientific paper should. -

Searchable PDF Format

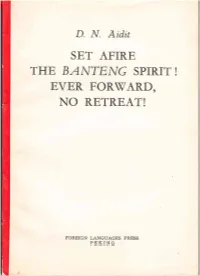

D. tr/. Atdtt SET AFIRE THE BAA{TEA/G SPIRIT ! EVER FOR$TARD, NO RETREAT! FOREIGN LANGUAGES PRESS PEKING D. N. Atdtt SET AFIRE THE BANTENG SPIRIT ! EVER FORSTARD, NO RETREAT ! Political Report to the. Second Plenum of the Seventh Central Committee of Communist Party of Indonesia, Enlarged with the Members of the Central Auditing Commission and the Central Control Commission (Djakarta, 23rd-26th December, 1963) FOREIGN I-ANGUAGES PRESS PEKING 1964 CONTENTS CONTTNUE FORWAED F'OR CONSISTENT LAND REFORDT. TO CRUSH 'MA.T,AYSTA" A.ND FOts THE FORMATION OF A GOTONG ROYONG CAEIhTET WITH NASA.KOM AS THE COREI o (1) FOOD AND CLOTI{ING (2) CRUSFI "NTALAYSIA" (3) CONTINUE WITH CONSTRUCTION 46 (a) 26th May, 1963 Economic Regulations 47 (b) The 1963 and 1964 State Budgets DI. (c) Economic Confrontation r,vith "Malaysia,, 52 (d) The Penetration of Imperralist Capital into Indonesia 55 (e) Back to the Dekon as the Cn15, Way to Continue with Economic Consiruction 57 II, CONTINUE TO CRUSH IIIIPERIAT,ISM AND REVI- SIONXSM! 63 (1) THE STRUGGLE TO CRUSH IMPERIALISM IS CONTINUING TO ADVANCE ON ALL FRONTS 12) IN ASIA, AFRICA AND LAIIIN AMERICA TFIERE IS A REVOLUTIONARY SITUA- TION THAT IS CONTINUOUSLY SURGING FORWARD AND RIPENIIVG 3) SOUTHEAST ASIA IS ONE OF THE CENTRAL POINTS IN TI]E REGION OF I\{AIN CON- TRADICTION 95 (4) IT WOULD BE BETTER IF TTIERE WERE NO MOSCOW TRIPARTITE AGREEMENT AT ALL 98 (5) COMNIUNIST SOCIETY CAN ONLY BE R,EALISED IF IMPERIALISM HAS BEEN WIPE.D OF'F T}IE EA,RTH 103 (O) 'I}ID INTERNATIONAL CONINTUNIST MOVE.