INDO 50 0 1106971426 29 60.Pdf (1.608Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

Failure of Bilateral Diplomacy on Irian Barat (Papua) Dispute (1950-1954)

FAILURE OF BILATERAL DIPLOMACY ON IRIAN BARAT (PAPUA) DISPUTE (1950-1954) Siswanto Center for Political Studies, The Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jakarta E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Fundamentally, Irian Barat (Papua) dispute between The Netherlands –Indonesia was a territorial conflict or an overlapping claim. The Netherlands as the former colonialist did not want to leave Irian Barat (Papua) or remained still in the region, meanwhile Indonesia as the former colony denied the Netherlands status quo policy in Irian Barat (Papua). Potential dispute of the Irian Barat (Papua) was begun in the Round Table Conference (RTC) 1949. There was a point of agreement in RTC which regulates status quo on Irian Barat (Papua) and it was approved by Head of Indonesia Delegation, Mohammad Hatta and Van Maarseven, Head of the Netherlands Delegation. As a mandate of the RTC in 1950s there was a diplomacy on Irian Barat (Papua) in Jakarta and Den Haag. Upon the diplomacy, there were two negotiations held by diplomats of both countries, yet it never reached a result. As a consequence, in 1954 Indonesia Government decided to stop the negotiation and searched for other ways as a solution for the dispute. At the present time, Jakarta-Papua relationship is relatively better and it is based on a special autonomy, which gives great authority to the Local Government of Papua. Keywords: the Netherlands, Indonesia, status quo, Irian Barat (Papua), diplomacy Abstrak Pada dasarnya perselisihan Irian Barat (Papua) antara Belanda –Indonesia adalah konflik teritorial atau tumpang tindih klaim. Belanda sebagai mantan penjajah tidak ingin meninggalkan Irian Barat (Papua) atau masih ingin menduduki kawasan itu, di sisi lain Indonesia sebagai bekas bangsa terjajah menolak kebijakan status quo Belanda di Irian Barat (Papua). -

Means Change!

Sports Program IG. W. Five Announces c For Local Fans Bivins • Prof. Predicts Louis Says TODAY. 26-Game Schedule Leahy Boxing. Is Tops, But Lazy Art Bethea vs. Lavery Roach, 'Poor Notre Dame' By the Associated Press eight-round welterweight fea- Under Coach Zahn ture, Turner’s Area, first bout LOS Nov. 4.-Joe A basket ball schedule ANGELES, 8:45. 26-game Louis that Cleveland’s says Hockey. has been announced: by George Jimmy Bivins would win a heavy- J director ot Will Lose to Army Washington Lions at Shawinl- Washington University's weight tournament, were one men’s1 activities, Max Farrington. gan Palls (Ont.) Cataracts. held now. with By Sid Feder Pro Basket Ball. The program includes games VExcept for Bivins,” Louis de- such generally strong quints as Associated Pross Sports Writer Washington Capitols at Pitts- clared, ‘‘all the heavies are about Maryland,1 Navy, William and Mary — burgh. SOUTH BEND, Ind., Nov. 4 the same. If he wasn’t so These four will be lazy TOMORROW. and: Seton Hall. Prof. Frank Leahy—better known he’d be head and shoulders above at Uline Hockey. played in games Arena, all the others.” tilts are at Tech as The Master—showed you there Washington Lions at Valley- while other home Joe was here for an Amer- was nothing up his sleeves and then field (Ont.) Braves. gym.I icanism rally. He leaves later Otts Zahn again will coach the that would WEDNESDAY. calmly announced Army this week for Honolulu and a 1 most- Wrestling. Colonial cagers. The material knock off his Notre Dame Irish next four-round exhibition, later go- the Weekly program at Turner's ly] will be green, with exception to Mexico for another. -

The Notre Dame Scholastic VOLUME 91, NUMBER 13 JANUARY 13, 1950 Examination Horror Falls on Campus

•The Notre Dame Too Little. Too Late January \^, \g^o PROVE TO YOURSELF NOCIBARETTC HANGOVER when you smoke PHILIP MORRIS! HERES ' Z^As, voo can RTfftS ALL YOU ,„ iust a .ew ^l PHILIP WORM* iif^i ^.. ««•« •t> Remember: less irritation means more pleasure. And PHIUP MORRIS is the ONE cigarette proved .. •. light up your definitely less irritating, present brand definitely milder, than . • • •••9''* "P^i* any other leading brand. PHIUP MORRIS 2Do exactly the tam\ntik^e tn^,.^thing —DON_ T u..:^ ,1,01 ijitj^ Hioi (ting? . -uff-DONT INHAIE INHALE. Notice that bite, that sting? NO OTHER OGARETTE I,HEN •.«;^Ve;P«« ^^ ^„,, .0^ „„.„_..- Quite a difference from PHIUP MORRIS! CAN MAKE THAT 1^^ -. A- NOW .. _ ^^ ^^^^,^^ ,,„, ,OR«IS. STATEMENT. HOW YOU KNOW WHY YOU SHOU _ K niUP MORRIS The Scholastic Letters mmm^<^:^4.!s Sunny Italy Room for Improvement? A Notre Dame Tradition Editor: The annual football issue of the SCHOLASTIC, like Frank Leahy's football team, keeps getting better and better, "Rosie's." Here You'll even though one wonders how there Always Enjoy the can be room for improvement. Just Italian Accent on how good can they get? It will be hard Fine Food. to top this latest one, however. The SUNNY ITALY CAFE Kodachrome cover is a dandy. 601 NORTH NILES William A. Page Fort Thompson, South Dakota. -•- Mistaken Identity Editor: AULT'S SHUTTER BUGS It seems that Dan Brennan has an Photography is an interesting apology to make to the Christian hobby. You'd be surprised how Brothers and Manhattan College. In economically you can become an his "Names Make News" column in the amateur photographer (Shut- Dec. -

United Nations List of Delegations to the Second High-Level United

United Nations A/CONF.235/INF/2 Distr.: General 30 August 2019 Original: English Second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation Buenos Aires, 20–22 March 2019 List of delegations to the second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation 19-14881 (E) 110919 *1914881* A/CONF.235/INF/2 I. States ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Gent Cakaj, Acting Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs H.E. Ms. Besiana Kadare, Ambassador, Permanent Representative Mr. Dastid Koreshi, Chief of Staff of the Acting Foreign Minister ALGERIA H.E. Mr. Abdallah Baali, Ambassador Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Alternate Head of Delegation H.E. Mr. Benaouda Hamel, Ambassador of Algeria in Argentina, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina Representatives Mr. Nacim Gaouaoui, Deputy Director, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Zoubir Benarbia, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Algeria to the United Nations Mr. Mohamed Djalel Eddine Benabdoun, First Secretary, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina ANDORRA Mrs. Gemma Cano Berne, Director for Multilateral Affairs and Cooperation Mrs. Julia Stokes Sada, Desk Officer for International Cooperation for Development ANGOLA H.E. Mr. Manuel Nunes Junior, Minister of State for Social and Economic Development, Angola Representatives H.E. Mr. Domingos Custodio Vieira Lopes, Secretary of State for International Cooperation and Angolan Communities, Angola H.E. Ms. Maria de Jesus dos Reis Ferreira, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission of Angola to the United Nations ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA H.E. Mr. Walton Alfonso Webson, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission Representative Mr. Claxton Jessie Curtis Duberry, Third Secretary, Permanent Mission 2/42 19-14881 A/CONF.235/INF/2 ARGENTINA H.E. -

Cleveland, Paul M

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR PAUL M. CLEVELAND Interviewed by: Thomas Stern Initial interview date: October 20, 1996 Copyri ht 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Boston - raised in New York and Washington Yale University, Georgetown University U.S. Air Force Entered Foreign Service - 19,9 State Department - Administration - A-OP. 19,7-19,9 Social Assistant to Tom Estes State Department - FS0 - German language training 19,9-1910 Canberra, Australia - Economic-Political officer 1910-1912 Personnel Environment Duties Papua New Guinea visit Australian immigration policy Bonn, Germany - Staff assistant to Ambassador 1912-1914 Ambassador George 7cGhee President 8ennedy9s visit Soviet problems Fletcher School 1914-191, Djakarta, 0ndonesia - Economic officer 191,-1918 U.S. investments and interests A0D program Petroleum explanation 7ining Anti-Americanism Sukarno9s coup 1 General Sukarno9s victory The "Berkeley 7afia" Bribery 0bnu Sukarno Ambassador 7arshall Green Comments on career development State Department - Office of Fuels and Energy 1918-1970 James Abim A learning experience Oil import contingency plan Latin America visit OPEC Efficiency reports State Department - East Asia - Special assistant to Asst. Secretary 1970-1973 Duties Personnel 8orea9s Yshin Constitution Dealing with the media Bill Sullivan State - NSC chain of command problems Henry 8issinger9s China trip China relations 7arshall Green - Assistant Secretary - EA Seoul, 8orea - Political-7ilitary officer; Political counselor 1973-1977 Local contacts orth-South 8orea relations U.S. military presence-withdrawal Duties Dealing with the U.S. military General Dick Stilwell U.S. military personalities JUS7AAG 7ilitary sales US-.O8 military exercises "8aeseng" houses C0A Contacts with 8orean opposition U.S. -

The Country Team and Local Staff Role | Excerpt from Inside a U.S. Embassy

PART II Foreign Service Work and Life: Embassy, Employee, Family By Shawn Dorman THE EMBASSY AND THE COUNTRY TEAM mbassies are located in the capital city of each country with which the United States has official relations, and serve as headquarters for U.S. gov - Eernment representation overseas. U.S. consulates are ancillary government offices in cities other than the capital. American and local employees serving in U.S. embassies and consulates work under the leadership of an ambassador to conduct diplomatic relations with the host country. The Department of State is the lead agency for conducting U.S. diplomacy and the ambassador, appointed by the U.S. president, reports to the Secretary of State. Diplomatic relations among nations, including diplomatic immunity and the inviolability of embassies, follow procedures framed by the 1961 Vienna Convention on the Conduct of Diplomatic Relations and Optional Protocols, ratified by the U.S. in 1969. The foreign affairs agencies that make up the Foreign Service—the Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Foreign Commercial Service, the Foreign Agricultural Service, and the International Broadcasting Bureau—are part of the overall U.S. mission in a country and usually have their offices inside the embassy. Each embassy can also be home to the offices of other U.S. government agencies and departments, in some countries as many as 40 dif - ferent entities. Agencies with a significant overseas presence include the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Drug Enforcement Agency, the Treasury Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Homeland Security. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 2014

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION APRIL 2014 GREENING EMBASSIES CHIEf-Of-MISSION GUIDELINES HOW H.A. GILES LEARNED CHINESE FOREIGN April 2014 SERVICE Volume 91, No. 4 AFSA NEWS FOCUS GREENING EMBASSIES AFSA Releases Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 45 Eco-Diplomacy: Building the Foundation / 20 VP Voice State: Collaborating with Our Partner Organizations / 46 U.S. embassies and consulates around the world are becoming showcases VP Voice Retiree: Retirement for American leadership in best practices and sustainable technology. Begins Before Retirement / 47 BY DONNA M. MCINTIRE VP Voice FCS: The Budget Resource Merry-Go-Round / 48 The Greening Diplomacy Initiative: Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 49 Capturing Innovation / 24 AFSA Hosts Chiefs of Mission / 51 AFSA On the Hill: State’s homegrown Greening Diplomacy Initiative relies on seeding, Beyond Advocacy Day / 52 harvesting, sifting, implementing and sharing employees’ innovations New Association Management and ideas, large and small. System for AFSA / 53 BY CAROLINE D’ANGELO AFSA VP Meets with Florida Retirees / 54 The League of Green Embassies: 2013 Sinclaire Award Recipients / 54 AFSA Book Notes: American Leadership in Sustainability / 30 America’s First Globals / 55 A coalition of more than 100 U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide AFSA Partners with United Nations shares ideas and practical experience in the field. Association / 56 BY JOHN DAVID MOLESKY FSJ Editor-in-Chief Steps Down / 56 AFSA and DACOR Salute U.S. Marine Security Guards / 57 Finns Take the LEED in Green Embassy Design / 35 The Foreign Service Family: The Finnish embassy in Washington, D.C., is a green building that The Packout and Me / 59 was ahead of its time. -

Table of Contents

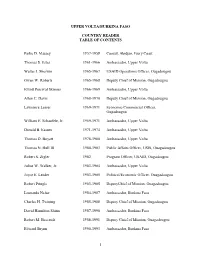

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers

Republic of Tunisia MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers – Biographies Hosts Mr. Beji Caïd Essebsi - President of the Republic - Tunisia Mr. Essebsi is the President of Tunisia since 2014. Previously, Mr. Essebsi held the position of Prime Minister for a brief period – March to October 2011. During his career, the President has held various high level positions, including Head of the Administration of National Security (1963), Minister of Interior from (1965-1969), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1981-1986) and President of the Chamber of Deputies (1990-1991). The President was also ambassador of Tunisia to West Germany and France. Mr. Youssef Chahed - Prime Minister - Tunisia Mr. Chahed was appointed Tunisian Prime Minister in August 2016. Before taking office, Mr. Chahed was Minister of Local Affairs in the previous government and previously held the position of Secretary of State for Fisheries. The Prime Minister is also an international expert in agriculture and agricultural policies for the United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the European Commission. Mr. Angel Gurría - Secretary-General - OECD Mr. Gurría is the OECD Secretary-General since 2006. The Secretary-General has held two ministerial posts in Mexico before joining the OECD - Minister of Foreign Affairs (1994-1998) and Minister of Finance and Public Credit (1998- 2000). Mr. Gurría chaired the International Task Force on Financing Water for All and is a member of several international initiatives, including the United Nations Secretary General Advisory Board, World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Water Security, International Advisory Board of Governors of the Centre for International Governance Innovation, among others. -

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

Charting the CFR’s Political Dominance • Rethinking Discrimination August 10, 2020 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com THAT FREEDOM SHALL NOT PERISH DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. NEW CHINA: THE DEEP STATE’S TROJAN HORSE IN AMERICA This exposé shows that the Chinese Communist plan to subvert America is well underway, and is being aided by the Deep State. Will Americans wake up before the tipping point? By Arthur R. Thompson, CEO, The John Birch Society (2020ed, pb, 132pp, 1-11/$7.95ea; 12-23/$5.95ea; 24-49/$3.95ea; 50+/$2.95ea) BKCDSTHA ✁ Order Online: Mail completed form to: QUANTITY TITLE PRICE TOTAL PRICE ShopJBS • P.O. BOX 8040 www.ShopJBS.org APPLETON, WI 54912 Credit-card orders call toll-free now! 1-800-342-6491 Name ______________________________________________________________ Address ____________________________________________________________ SHIPPING/HANDLING WI RESIDENTS ADD City _____________________________ State __________ Zip ________________ SUBTOTAL (SEE CHART BELOW) 5.5% SALES TAX TOTAL Phone ____________________________ E-mail ______________________________ 0000 ❑ ❑ ❑ 000 0000 000 000 For shipments outside the U.S., please call for rates. Check VISA Discover 0000 0000 0000 00 Order Subtotal Standard Shipping Rush Shipping ❑ Money Order ❑ MasterCard ❑ American Express VISA/MC/Discover American Express Three Digit V-Code Four Digit V-Code $0-10.99 $6.36 $9.95 Standard: 4-14 $11.00-19.99 $7.75 $12.75 business days. Make checks payable to: ShopJBS ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ $20.00-49.99 $9.95 $14.95 Rush: 3-7 business $50.00-99.99 $13.75 $18.75 days, no P.O. -

World Health Assembly

OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION No. 128 SIXTEENTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY GENEVA, 7 - 23 MAY 1963 PART II PLENARY MEETINGS Verbatim Records COMMITTEES Minutes and Reports WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA December 1963 The following abbreviations are used in the Official Records of the World Health Organization: ACABQ Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions ACC Administrative Committee on Co- ordination BTAO Bureau of Technical Assistance Operations CCTA Commission for Technical Co- operation in Africa CIOMS - Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences ECA Economic Commission for Africa ECAFE - Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East ECE - Economic Commission for Europe ECLA - Economic Commission for Latin America FAO Food and Agriculture Organization IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization ILO - International Labour Organisation (Office) IMCO Inter -Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization ITU - International Telecommunication Union MESA - Malaria Eradication Special Account OIHP Office International d'Hygiène Publique OPEX Programme (of the United Nations) for the provision of operational, executive and administrative personnel PAHO - Pan American Health Organization PASB - Pan American Sanitary Bureau SMF Special Malaria Fund of PAHO TAB Technical Assistance Board TAC - Technical Assistance Committee UNESCO - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNICEF - United Nations Children's Fund UNRWA -